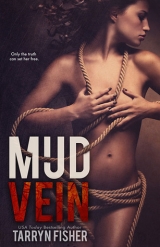

Текст книги "Mud Vein"

Автор книги: Tarryn Fisher

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

Nick's Book: Chapter Two

Nick’s Book

She came back. Two days later. I saw her from my living room window, standing in the same spot I’d left her, staring at my house as if it were something out of a bad dream. The last time I saw her she’d been standing in sunshine, this time it was rain. She had on a white slicker, the rim of it dripping water into her face. I could see the silver streak in her hair plastered to her cheek. I watched her from the window for a few minutes, just to see what she’d do. She seemed rooted to the spot. I decided to go get her. Walking barefoot down my driveway, I sipped my coffee casually, running my tongue over the chip in the rim. A few raindrops dripped into my mug. When I came within a few feet of her I stopped and looked up at the sky.

“You like this weather.” It wasn’t a question.

“Yes,” she said.

I nodded. “Want to come in for some coffee?”

Instead of answering me she started walking up the driveway, helping herself to the door. It slammed behind her before I realized she was alone in my house.

Was it my imagination, or did she make sure to step on every weed on her way up?

She didn’t stop to look around when she walked through the corridor that connected my foyer to the rest of the house. I had several pictures hanging on my walls—art and some family stuff. Normally women stopped to examine each one. I always thought they did it to ease their nerves. She took off her jacket and dropped it on the floor. Puddles formed around it as the rainwater skirted off. She was an odd bird. She walked right to the kitchen like she’d been there a hundred times before, stopping in front of my beat-up Mr. Coffee. She pointed to the cabinet above it, and I nodded. She chose a Dr. Seuss mug—smart girl. I tended to stick to the Walt Whitman with the chip on the rim. I watched her lift the pot from the warmer and pour without looking. She was staring out my window. Right when the liquid reached the rim of the mug, her hand automatically pulled back. I breathed a sigh of relief. She had the weight and timing perfected in that strange little head of hers. When she was done, she leaned back against the counter and looked at me expectantly.

“So, the other day…”

“What?” I said. “You’re the one that just left.”

“It wasn’t the right day.”

What the hell type of thought was that?

“And today is the right day?”

She shrugged. “Maybe. I just felt like coming, I guess.”

She ambled over and sat across from me at the worn dinette I’d taken through three relationships. If I ended up with this girl I was going to buy a new table. I’d had sex on it too many times for it to be relationship kosher.

“This is a stupid world,” she said, and traced her finger along the edge of the table like she was reading brail.

I waited for her to go on but she didn’t. My forehead was creased. I felt the skin wrinkling against itself. She was sipping her coffee, already thinking about something else.

“Do you ever have a complete thought?”

She seriously considered my question and languidly took another sip. “I have many.”

“Finish the last one then.”

“I don’t remember what it was.”

She drank the rest of her coffee, then stood up to leave.

“See you Tuesday,” she said, heading for the door.

“What’s Tuesday?” I called after her.

“Dinner at your house. I don’t eat pork.”

I heard the screen slam behind her. Max raced for the door, barking, his nails clicking against the tile as he scrambled past me. I leaned back in my chair, smiling. I didn’t eat pork either. Except bacon, of course. Everyone eats bacon.

She showed up on Tuesday, right at six. I had no idea when to expect her, so I made sushi with the salmon I’d bought that morning from the market. I was busy wrapping my rolls in seaweed when she let herself in. I heard the screen door slam and Max’s manic barking.

She slid a bottle of whiskey across the counter.

“Most people bring wine,” I said.

“Most people are pussies.”

I choked on my laugh.

“What’s your name?”

“Brenna. What’s yours?”

“You already know my name.”

It was mostly true. She knew my pen name.

“Your real name,” she said.

“It’s Nick Nissley.”

“So much better than John Karde. Who are you hiding from?”

She unscrewed the lid from the Jack and drank straight from the bottle.

“Everyone.”

“Me, too.”

I looked at her out of the corner of my eye as I poured soy sauce into two ramekins. She was young, much younger than me. What did she have to hide from? Probably an ex-boyfriend. Nothing serious. Just a guy who didn’t want to let go, most likely. I had some exes who probably wanted to hide from me. It was a shallow thought, because if this woman was really that simple, she wouldn’t have struck my interest. I saw her standing still and quiet, and she caused movement in my brain. I’d already written over sixteen thousand words since she’d walked with me to my house and then disappeared. A feat, considering I’d been claiming writer’s block for the last year of my life.

No, if this woman said she was running away, she was.

“Brenna,” I said that night as we lay in my bed.

“Mmmm.”

I said it again, tracing a finger along her arm.

“Why do you keep saying my name?”

“Because it’s beautiful. I’ve known Brianna’s, but never a Brenna.”

“Well, congratulations to you.” She rolled off the bed and reached for her skirt. That skirt had been what started it all. I see a skirt and I want to know what’s underneath it.

“Where are you going?”

The corner of her mouth lifted. “Do I look like the kind of girl who sleeps over on the first date?”

“No ma’am.”

She fished around on the floor for the last of her clothes, and then I walked her to the door.

“Can I take you home?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

“I don’t want you to know where I live.”

I scratched my head. “But you know where I live.”

“Exactly,” she said. She pushed up on her toes and kissed me on the mouth.

“Tastes like a New York Times Bestseller,” she said. “Goodnight, Nick.”

I watched her go and felt conflicted. Did I really just let a woman walk out of my house in the middle of the night and not take her home? I hadn’t seen a car. My mother would have a coronary. I knew so little about her, but there was no question that she wouldn’t take well to me galloping after her on my imaginary steed. And why the hell didn’t she drive? I walked back into the kitchen and started cleaning up our dinner plates. We had only made it through half of the sushi before I leaned across the table and kissed her. She hadn’t even acted surprised, just dropped her chopsticks and kissed me back. The rest of our night was impressively graceful. I credit her with that. She undressed me in the kitchen and made me wait to take her clothes off until we reached the bedroom. Then she made me sit on the edge of the bed while she undressed herself. Her back never touched the sheets. A true control freak.

I put the last of the dishes in the dishwasher and sat at my desk. My thoughts were coming at me fast. If I didn’t get them down, I’d lose them. I wrote ten thousand words before the sun came up.

A week later we took our first trip into Seattle together. It was her idea. We rode in my car since she said she didn’t have one. She looked nervous sitting in the front seat with her hands folded in her lap. When I asked her if she wanted me to put on the radio she said no. We ate Russian pastries from paper bags and watched the ferries cross the sound, shivering and standing as close as we could get to each other. Our fingers were so greasy when we were done we had to rinse them off in a water fountain. She laughed when I splashed water in her face. I could have written another ten thousand words just from hearing her laugh. We bought five pounds of prawns from the market and headed back to my house. I don’t know why the hell I asked for five pounds, but it sounded like a good idea at the time.

“You have one of these,” I said, as we were cleaning the prawns together at my kitchen sink. I ran my finger laterally along its body, pointing out the dark line that needed to be cleaned out. She frowned, looking down at the prawn she was holding.

“It’s called a mud vein.”

“A mud vein,” she repeated. “Doesn’t sound like a compliment.”

“Maybe not to some people.”

She de-headed her shrimp with a flick of her knife and tossed it in the bowl.

“It’s your darkness that pulls me in. Your mud vein. But sometimes having a mud vein will kill you.”

She set down the knife and washed her hands, drying them on the back of her jeans.

“I have to go.”

“Sure,” I said. I didn’t move until I heard the screen door slam. I wasn’t upset that my words had run her off. She didn’t like to be found out. But she’d be back.

Nick's Book: Chapter Three

Nick’s Book

She didn’t come back. I tried to tell myself that I didn’t care. There were plenty of women. Plenty. There were women everywhere I looked. They all had skin and bones, and I’m sure some of them even had silver streaks in their hair. And if they didn’t have a silver streak in their hair I’m sure I could convince them to put it there. But there is something about the process of convincing yourself that you don’t care that just confirms even more that you do. Every time I passed the window in my kitchen I found myself looking up to see if she was standing in the rain, judging the weeds poking out of the driveway. I looked at those weeds so much that eventually I went out there in the rain and pulled them up one by one. It took me all afternoon and I got a nasty head cold. I was cleaning up my driveway for a woman.

I wanted to go look for her, but she’d told me little to nothing about herself. I could hold the five things she’d said in the palm of my hand, and still find plenty of room. Her name was Brenna. She came from the desert. She liked to be on top. She ate bread by pulling off little pieces and placing them in the center of her tongue. I had asked her questions, and she had skillfully turned them back on me. I had been eager to give her answers—too eager—and in the process I’d forgotten to collect answers from her. She had played me like a narcissistic trombone. Tooting, tooting, tooting my own horn. She must have been thinking what a fool I was the entire time.

Toot, toot.

I went back to the park, hoping to run into her again. But something told me that day in the park was a fluke. It wasn’t her day to be there, and it wasn’t mine. We met because we needed to, and I’d gone and screwed it up by telling her she had a mud vein. I thought she knew. God. If I had another chance with her, I’d never talk again. I’d just listen. I wanted to know her.

I sat in front of my laptop and wrote more words than had come to me in years—all at once. They just strung themselves together and I felt like a writing god. I had to have more of this woman. I’d write a library full of books if I had a year with her. Imagine a lifetime. She was meant for me. I cleaned out my weeds, I cleaned out my closets, I bought a new table and chairs for my kitchen. I finished my book. E-mailed it to my editor. I lingered some more at my kitchen window, industriously washing and rewashing my dishes.

It was Christmas before I found her again. Actual Christmas—the day of tinsel and turkey and colorful paper wrapped around goodies we don’t want or need. I have a mother and a father and twin sisters with rhyming names. I was on my way to their house for Christmas dinner when I saw her jogging along the barren sidewalk. She was headed for the lake, her fluorescent sneakers blurring beneath her. She was a flash of speed. Her legs were chorded with muscle. I’d bet she could outrun a deer if she tried. I sped up and pulled into the empty lot of an Indian restaurant about half a mile ahead of her. I could smell the curries seeping from the building: green and red and yellow. I hopped out of my car and crossed the street, planning to cut her off before she reached the lake. She would have to go through me to get to the trail. I looked bolder than I felt. She could tell me to go to hell.

By the time she saw me it was too late to pretend she hadn’t. Her pace slowed until she was bent at the knees in front of me. I watched the way her back rose and fell. She was breathing hard.

“Merry Christmas,” I said. “Sorry for interrupting your run.”

She glared at me from her bent position, confirming my guess that she didn’t want to see me.

“I didn’t mean to upset you the last time you were at my house,” I said. “If you’d given me the chance to apologize I wo—”

“You didn’t upset me,” she said. And then, “I finished my book.”

Finished her book? I gaped. “In the three weeks I haven’t seen you? I thought you’d barely started.”

“Yes, and now I’ve finished it.”

I opened and closed my mouth. It took me a year to complete a manuscript, and that didn’t include the time I spent on research.

“So when you just left like that…?”

“I knew what I had to write,” she said, like it was the most obvious thing in the world.

“Why didn’t you say something? Call me?” I felt like a clingy high school girl.

“You’re an artist. I thought you’d understand.”

I was wrestling with my pride to tell her that I didn’t. I’d never in my life run out on dinner to finish a story. I’d never felt even a chord of passion strong enough to drive me to do that. I didn’t tell her because I was afraid of what she would think. Me—New York Times Bestseller of over a dozen sappy novels.

“What did you write about?” I asked.

“My mud vein.”

I got a chill.

“You wrote about your darkness? Why would you do that?”

There was nothing pretentious about her. No show, no thriving to impress me. She didn’t even try to guard the ugly truth, which made every one of her words feel like a cold dousing of water to the face.

“Because it was the truth,” she said, so matter of fact. And I fell in love with her. She didn’t have to try to be anything. And everything that she was was something that I was not.

“I missed you,” I said. “Can I read it?”

She shrugged. “If you want to.”

I watched a trickle of sweat wind down her neck and disappear between her breasts. Her hair was damp, her face flushed, but I wanted to grab her and kiss her.

“Come with me to my parents’. I want to have Christmas dinner with you.”

I thought she was going to say no and I’d have to spend the next ten minutes convincing her. She didn’t. She nodded. I was too afraid to say anything as she walked with me to my car, in case she changed her mind. Without any objections, she climbed into the front seat and folded her hands in her lap. It was all very formal.

As soon as we were on the road, I reached for the radio. I wanted to put on Christmas music. At least prepare her for the Christmas crack she was about to experience at the Nissley house. She grabbed my hand.

“Can you leave it off?”

“Sure,” I said. “Not a fan of music?”

She blinked at me, then looked out the window.

“Everyone is a fan of music, Nick,” she said.

“But not you…?”

“I didn’t say that.”

“You implied it. I’m begging for a detail about you, Brenna. Just give me one.”

“Okay,” she said. “My mother loved music. She played it in our house from morning ‘til night.”

“And that made you dislike it?”

We pulled into my parent’s driveway and she used the distraction to avoid answering my question.

“Pretty,” she said as we slowed to a stop.

My parents lived in a modest home. They’d spent the last ten years making upgrades. If she thought the outside was pretty I couldn’t wait to see what she thought of my mother’s pink granite kitchen counters, or the fountain depicting a peeing boy they installed in the middle of the foyer. When I lived at home we’d had linoleum and plumbing that only worked a tenth of the time. She made no comment about the giant reindeer lawn ornaments, or the wreath almost the size of the front door. She hopped out without any reservation and followed me to the house of my very happy childhood. I looked at her before I opened the door, dressed in running clothes, her hair messy and stuck to her face. What type of woman jumped in the car with you on Christmas Day to meet your family, without putting on a cardigan and a dress? This one. She made every woman I’d ever been with feel insignificant and fake. This was going to be fun.

Chapter Twenty

“Is this you, Senna?”

He was looking at me intensely. I didn’t know what he was thinking, but I knew what I was thinking: Damn Nick and his book.

I could barely … I didn’t know how to … My thoughts were trembling out of my hands.

“You’re shaking,” Isaac said. He set the book on the nightstand and poured me a glass of water. The cup was one of those heavy plastic things, the color of too many colors of Play-Doh mixed together. It grossed me out, but I took it and sipped. The cup felt too heavy. Some of the water spilled down the front of my hospital gown, plastering it to my skin. I handed the cup back to Isaac, who set it aside without taking his eyes off my face. He put each one of his hands over mine to steady them. It absorbed a little of my shaking.

“He wrote this for you,” Isaac said. His eyes were dark, like he had too many thoughts and they were filling him up. I didn’t want to answer.

There was no mistaking the similarities in name—Senna/Brenna. There was also no mistaking the actual story itself. The fine line that squiggled between fiction and truth. It made me sick that Nick told the story. Our story? His version of our story. Some things should be buried and left to rot.

I pointed to the book. “Take it,” I said. “Throw it away.”

His eyebrows drew together. “Why?”

“Because I don’t want the past.”

He stared at me for a long minute, then picked up the book, tucked it under his arm and walked for the door.

“Wait!”

I held out my hand for the book and he walked it back to me. Opening the cover I flipped to the dedication, touching it softly, running my fingers over the words … then I ripped it out. Hard. I handed the book back to Isaac, with the jagged page clutched in my fist. Stone faced, he left, the soles of his shoes sucking on the hospital floor. Thwuup ... Thwuup … Thwuup. I listened until they disappeared.

I folded the page over and over until it was the size of my thumbnail, square upon square upon square. Then I ate it.

I was discharged a week later. The nurses told me that normally a double mastectomy patient went home after three days, but Isaac pulled strings to keep me there longer. I didn’t say anything about it as he handed me my prescriptions in a paper bag, folded over twice and stapled. I shoved the bag into my overnight bag, trying to ignore the rattling sound of the pills. Trying to ignore how heavy the bag was in general. I supposed that it was easier for him to keep an eye on me here rather than at my house.

He moved surgeries around and took the afternoon off to take me home. It annoyed me, and yet I didn’t know what I’d do without him. What did you say to a man who inserted himself as your caretaker without your permission? Stay away from me, what you’re doing is wrong? Your kindness freaks me out? What the hell do you want from me? I didn’t like being someone’s project, but he had his wits and car, and I was laced with painkillers.

I wondered what he did with Nick’s book. Did he toss it in the trash? Put it in his office? Maybe when I got home it would be sitting on my night table like it had never left.

A nurse wheeled me through the hospital to the main doors where Isaac had parked his car. He walked slightly ahead of me. I watched his hands, the fat of his palm beneath his thumb. I was looking for traces of the book on his fingers. Stupid. If I wanted Nick’s words, I should have read them. Isaac’s hands were more than Nick’s book. They’d just reached into my body and cut out my cancer. But I couldn’t stop seeing the book in his hands, the way his fingers lifted the corner of the page before he turned it.

He put on wordless music when we got in his car. That bothered me for some reason. Perhaps I expected him to have something new for me. I tapped my finger on the window as we drove. It was cold out. It would be like this for another few months before the weather would crack, and the sun would start to warm Washington. I liked the feel of the cold glass on my fingertips, like tiny shocks of winter. Isaac carried my bag inside. When I got to my room my eyes found my nightstand. There was a clear rectangle cut in the dust. I felt a pang of something. Grief? I was feeling a lot of grief; I had just lost my breasts. It had nothing to do with Nick, I told myself.

“I’m making lunch,” Isaac said, standing just outside my room. “Do you want me to bring it up here?”

“I want to shower. I’ll come down after.”

He saw me staring at the bathroom door and cleared his throat. “Let me take a look before you do that.” I nodded and sat down on the edge of my bed, unbuttoning my shirt. When I was finished, I leaned back, my fingers gripping the comforter. You’d think I’d be used to this by now—the constant gawking and touching of my chest. Now that there was nothing there I should feel less ashamed. I was just a little boy as far as what was underneath my shirt. He unwound the bandages from my torso. I felt the air hit my skin and my eyes closed automatically. I opened them, defying my shame, to watch his face.

Blank

When he touched the skin around my sutures I wanted to pull back. “The swelling is down,” he said. “You can shower since the drain is out, but use the antibacterial soap I put in your bag. Don’t use a sponge on the stitches. They can snag.”

I nodded. All things I knew, but when a man was looking at your mangled breasts he needed something to say. Doctor or not.

I pulled my shirt closed and held it together in a fist.

“I’ll be downstairs if you need me.”

I couldn’t look at him. My breasts weren’t the only thing torn and ripped. Isaac was a stranger and he had seen more of my wounds than anyone else. Not because I chose him like I did Nick. He was just always there. That’s what scared me. It was one thing inviting someone into your life, choosing to put your head on the train tracks and wait for imminent death, but this—this I had no control over. What he knew, and what he’d seen about me brought so much shame I could barely look him in the eyes. I tiptoed to the bathroom, glancing once more at the nightstand before shutting the door.

Someone could take your body, use it, beat it, treat it like it’s a piece of trash, but what hurts far worse than the actual physical attack is the darkness it injects into you. Rape works its way into your DNA. You aren’t you anymore, you’re the girl who was raped. And you can’t get it out. You can’t stop feeling like it’s going to happen again, or that you’re worthless, or that anyone could ever want you because you’re tainted and used. Someone else thought you were nothing, so you assume that everyone else will as well. Rape was a sinister destroyer of trust and worth and hope. I could fight cancer. I could cut chunks out of my body and inject poison into my veins to fight cancer. But I had no idea how to fight what that man took from me. And what he gave me—fear.

I didn’t look at my body when I undressed and stepped into the shower. It wouldn’t be me in that mirror. Over the last few months my eyes had emptied out, become hollow. When I happened upon my reflection somewhere, it hurt. I stood with my back to the water, like Isaac told me, and my eyes rolled back in my head. This was my first shower since the surgery. The nurses had given me a sponge bath, and one had even washed my hair in the little bathroom. She’d pushed a chair right up against the rim of the sink and had me bend my head back while she massaged little bottles of shampoo and conditioner into my hair. I let the water run over me for at least ten minutes before I had the nerve to reach up and soap the empty place below my collar bone. I felt…nothing.

When I was finished, patted dry and dressed in pajama pants, I called Isaac upstairs. Some of my steri-strips had come loose. I stood quietly as he worked to fit new ones on, my wet hair dripping down my back, my eyes closed. He smelled like rosemary and oregano. I wondered what he was making downstairs. When he was done, I slipped on a shirt and turned my back to him while I buttoned up the front of it. When I turned back around Isaac was holding the hairbrush I’d tossed on the bed. I’d been unsure of how to lift my arms high enough to work out the tangles. Pouring shampoo on my head had been one thing, brushing felt like an impossible feat. He gestured to the stool in front of my vanity.

“You’re so strange,” I said, once I was seated. I was working hard to keep my eyes on his reflection and not look at my face.

He glanced down at me, his strokes gentle and even. His fingernails were square and broad; there was nothing messy or ugly about his hands.

“Why do you say that?”

“You’re brushing my hair. You don’t even know me, and you’re in my house brushing my hair, cooking me dinner. You were a drummer and now you’re a surgeon. You hardly ever blink,” I finished.

His eyes looked so sad by the time I finished that I regretted saying it. He ran the brush through my hair one last time before setting it on the vanity.

“Are you hungry?”

I wasn’t, but I nodded. I stood and let him lead me out of my room.

I glanced once more at my nightstand before I followed him to the food.

People lie. They use you and they lie, all the while feeding you bullshit about being loyal and never leaving you. No one can make that promise, because life is all about seasons, and seasons change. I hate change. You can’t rely on it, you can only rely on the fact that it will happen. But before it does, and before you learn, you feel good about their stupid, bullshit promises. You choose to believe them, because you need to. You go through a warm summer where everything is beautiful and there are no clouds—just warmth, warmth, warmth. You believe in a person’s permanence because humans have a tendency to stick to you when life is good. I call them honey summers. I’ve had enough honey summers in life to know that people leave you when winter comes. When life frosts you over and you’re shivering and layering on as much protection as you can just to survive. You don’t even notice it at first. The cold makes you too numb to see clearly. Then all of a sudden you look up and the snow is starting to melt, and you realize you spent the winter alone. That makes me mad as hell. Mad enough to leave people before they left me. That’s what I did with Nick. That’s what I tried to do with Isaac. Except he wouldn’t leave. He stayed all winter.