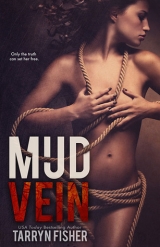

Текст книги "Mud Vein"

Автор книги: Tarryn Fisher

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

Chapter Thirty-One

They never found the man who raped me. There was never another report of a rape in those woods, or any woods in Washington. The police said it was an isolated incident. With blithe nonchalance, they told me that he had probably been watching me for a while and possibly followed me into the woods. They used words like “intent” and “stalker”. I’d had those before: letters, e-mails, Facebook messages that went from high praise to intense anger when I didn’t respond. None of them were men. None threatening enough to concern me. None with the tone of a rapist, or a sadist, or a kidnapper. Just angry moms who wanted something from me—recognition maybe.

But there was something I never told the police about the day I was raped. Even when they pressed me for more details. I couldn’t bring myself to say it.

No, I didn’t see his face.

No, he didn’t have tattoos or scars.

No, he didn’t say anything to me…

The truth was that he did speak to me. Or perhaps he just spoke. To God, to the air, to himself, or perhaps to some person who abandoned him. I can still hear his voice. I hear it when I sleep, whispering in my ear and I wake up screaming. From the moment he started to the moment he finished, he chanted one thing over and over.

Pink Zippo

Pink Zippo

Pink Zippo

Pink Zippo

It was an omission. Maybe he got away because of it. Maybe another woman will be raped because I could have done more. But in that moment, when you’ve been violated, your soul darkened for no reason other than someone’s sadistic cruelty, you’re only thinking about your survival.

I didn’t know how to live with my survival, and I didn’t know how to kill myself. Instead, I plotted what I’d do to him. While Isaac was feeding me, and pulling me out of dreams that made me thrash and scream, I was cutting up my rapist, throwing him into Lake Washington. Pouring gasoline over him and burning him alive. I was carving his skin like Lisbeth Salander did to Nils Bjurman. I took the revenge I would never get in my flesh and blood life.

But it wasn’t enough. It’s never enough. So I took revenge on myself for allowing it to happen. I felt worthless. I didn’t want anyone who had worth to be near me. Isaac had worth. So I got rid of him. But here we were; locked up and caged. Starved. The man who chanted Pink Zippo might have been a stalker, but he had nothing, nothing on the zookeeper. You can stalk a woman’s body, but this animal was stalking my mind.

My cast hits something. Isaac flicks the switch that turns on the bulb above the door. It’s been so long since light and not darkness has been my companion that it takes a moment for my eyes to catch up. The zookeeper has indeed left me something; a box, rectangular in shape, it reaches my knees. The box is pure white, shiny and smooth like the inlay of an oyster shell. On its lid are red words, the letters look as if someone dipped a finger in blood words that look as if someone dipped a finger in blood before tracing them. For MV.

My reaction is internal. The very essence of me writhes as if I am an open wound and someone has poured salt over me like one of those snails the kid next door used to torture. I hobble forward and lean over the box. Please God, please, don’t let it be blood.

Not blood.

Not blood.

My hand is shaking as I reach down to touch the words. I go for the V, slicing it in half. It has dried, but some of it chips away on the tip of my finger. I place my finger in my mouth, the flecks of red clinging to my tongue. All this, and Isaac has been a statue behind me. When I bend over, letting my crutch drop away, moaning in some sort of grief, I feel his arms circle my waist. He pulls me back into the house and kicks the door closed.

“Noooooo! It’s blood, Isaac. It’s blood. Let me go!”

He holds me from behind as I twist to get away from him.

“Hush,” he says into my ear. “You’re going to hurt your leg. You can sit on the sofa, Senna. I’ll bring it to you.”

I stop fighting. I’m not crying, but somehow my nose is running. I reach up and wipe it as Isaac carries me to the living room and sits me down. The couch is barely a couch. We hacked parts of it away to burn when we discovered that there was a wooden frame underneath the stuffing. The cushions are gouged; they sink beneath me. The back of the sofa is gone; there is nowhere to rest my back. I sit straight, my leg poking out in front of me. My anxiety climbs every second that Isaac is gone. My ears follow him to the door, where his breath hitches as he lifts the box. It’s heavy. The door closes again. When he walks back into the room he’s carrying it like a body, his arms stretched around its sides. There is no coffee table to set it on—we hacked that up too—so he places it at the floor by my feet, and steps back.

“What’s MV, Senna?”

I stare at the blood, the part of the V that I smudged with my finger.

“It’s me,” I say.

He tilts his head forward. It feels like he’s lining up our eyes. Truth. I’m going to have to feed him some truth.

“Mud Vein. I’m Mud Vein.” My mouth feels dry. I want to purge it with a gallon of snow.

His eyes flicker. He’s remembering.

“The dedication in his book.”

Our eyes are connected, so I don’t need to nod.

“Would he…?”

“I don’t know anything anymore.”

“What does it mean?” he asks. I lower my eyes away from his, and to the blood letters. For MV

“What’s inside?” I ask.

“I’ll open it when you tell me why the zookeeper addressed that box to Mud Vein.”

The box is just out of my reach. To get to it I’ll have to use something to pull myself up. Since the couch no longer has a back, there is nothing I can use for leverage. Isaac, I realize, is being very strategic. I take a breath; it is broken in half by a sob that never reaches my lips. My chest convulses as I open my mouth to speak. I don’t want to tell him anything, but I must.

“It’s the black vein that curves around the back of a shrimp. Nick called it the mud vein. You have to remove it to make the shrimp clean…” My voice is monotone.

“Why did he call you that?”

When Isaac and I ask each other questions it reminds me of a tennis match. Once you’ve sent one over the net, you know it’s going to come back, you just don’t know the direction.

“Isn’t it obvious?”

He blinks at me. One second, two seconds, three seconds…

“No.”

“I don’t get you,” I say.

“You don’t get you,” he shoots back.

We have resumed our eye transmissions. I’m glaring, but his stare is more candid. After a minute he steps over to the box and opens it. I try not to lean forward. I try not to hold my breath, but there is a white box with the words For MV stenciled on the lid in blood. I am aching to know what’s inside.

Isaac reaches down. I hear the gentle whisper of paper. When his hand comes up he’s holding a loose page that looks as if it’s been torn from a book. The corners have soaked up some blood.

For MV

Blood soaked pages, for MV…

Who knew that Nick called me that, besides Nick himself?

Isaac starts to read. “The punishment for her peace was upon him, and he gave her rest.”

I hold out my hand. I want to see the page, know who wrote it. It wasn’t Nick; I know his style. It wasn’t me. I take the blood-stained page, careful to keep my fingers away from the red parts. I read silently what Isaac read out loud. The page is numbered 212. There is no title or author name. I read through the rest of it, but I have the feeling that those are the words I was meant to see first. Isaac hands me another page, this one with a spot of blood the size of my fist blooming out from the middle of the page like a flower. The font is different, as is the size of the page. I rub it between my fingers. I know this feel; it’s Nick’s book. This is Knotted.

Isaac pushes the box closer to where I’m sitting so that I’m able to reach inside. The pages are all pulled from their binding, lined in four rows. I lift another page. The style lines up with the first book, lyrical with an old-fashioned feel to the prose. There is something strange about the writing, something I know I should remember, and cannot. I start pulling out pages at random. Separating the pages of Nick’s book from the new one. I work quickly, my fingers lifting and piling, lifting and piling. Isaac watches me from where he leans against the wall, his arms folded, lips pursed. I know that underneath his lips his two front teeth slightly overlap. I don’t know why I have this thought, at this time, but as I sort pages my thoughts are on Isaac’s two front teeth.

I am about halfway through the box when I realize that there is a third book. This one is mine. My fingers linger over the bright white pages—white because I told the publisher if they printed on cream I would sue them for breach of contract. Three books. One written for MV, one written for Nick … but the third…? My eyes reach over to the unknown pile. Who belongs to that book? And what is the zookeeper trying to tell me? Isaac pushes himself off the wall and steps toward the pile that belongs to Nick.

“We have to finish reading this one,” he says. My face drains of blood and I can feel a tingling along the tops of my shoulders as they tighten.

I hand him the pile. “It’s out of order and the pages aren’t numbered. Good luck.” Our fingers touch. Gooseflesh rises on my arms and I look away quickly.

Chapter Thirty-Two

We work to set the books in order. Through the longest night, the night that never ends. It’s good to have something to do, to keep you from waltzing down crazy street—not that we haven’t already been there. It’s a street you only want to visit a couple times in your life. We have power again … heat. So we take advantage by not sleeping, our fingers flying over pages, our brows creased with the strain. Isaac has Nick’s book. I take on the task of the other two—mine and…? It seems that there are too many pages to make up only three books. I wonder if we will discover a fourth.

Even as I come across pages of Knotted and hand them to Isaac, it is the nameless book that catches my attention. Each page has a line that pulls at my eyes. I read them, re-read them. No one I know writes this way, yet it is so familiar. I feel a lust for this author’s words. A jealousy at being able to string such rich sentences together. The first line keeps coming back to me with each subsequent line I read. The punishment for her peace was upon him, and he gave her rest.

I don’t notice when Isaac disappears from the room to make us food. I smell it when he comes back and hands me a bowl of soup. I set it aside, intent on finishing my work, but he picks it up and places it back in my hands.

“Eat it,” he instructs me. I don’t realize how hungry I am until I reluctantly place the spoon in my mouth, sucking the salty brown broth. I set the spoon aside and drink from the bowl, my eyes still scanning the piles set neatly around me. My leg is aching, as is my back, but I don’t want to stop. If I ask Isaac to help me move he will guess at my discomfort and force me to rest. I rub the small of my back when he’s not looking, and press on.

“I know what you’re doing,” he says, as he leans over his pile of pages.

I look up in surprise. “What?”

“When you think I’m not looking, I am.”

I flush, and my hand automatically reaches for my aching muscles. I pull back at the last minute and curl my hand into a fist instead. Isaac snickers and shakes his head, turning back to his work. I’m glad he doesn’t press the issue. I pick up another page. It’s my own. The story I wrote for Nick. Instead of putting it on its pile, I read it. True and trite. It was my call to him. The first line of the book went like this:

Every time you want to remember what love feels like, you look for me.

That line grabbed every woman who had ever offered their throbbing little heart to a man. Because we all have someone who reminds us of what love stings like. That unreliquished love that slips between our fingers like sand. The second line of the book confused them a little. It’s why their eyes kept following my trail of words. I was dropping breadcrumbs for the disaster that was to come.

Stay the fuck away from me.

I only wrote the book because he wrote one for me. It seemed fair. Most people text, or call, or write e-mails. My love and I write each other books. Hey! Here’s a hundred thousand words of ‘Why the hell did we break up anyway?’ It was Nick who had finally crippled me; it was Nick who took my belief away. And I decided sometime after I filed the restraining order against Isaac that it was a story worth telling.

When we broke up it was his choice. Nick liked to love me. I was not like him, and he valued that. I think I made him feel more like an artist because he didn’t know how to suffer until I came into his life. But he didn’t understand me. He tried to change me. And that was our destruction. And then Isaac read that book to me, perched on the edge of my hospital bed, my breasts sitting in a medical waste container somewhere. Suddenly I was hearing Nick’s thoughts, seeing myself as he saw me, and I heard him calling to me.

Nick Nissley was perfect. Perfect looking, perfectly flawed, perfect in everything he said. His life was graceful and his words were whetted to poignancy—both written and spoken. But he didn’t mean any of them. And that was the greatest disappointment. He was a pretender, trying to grasp what it felt like to live. So, he found me looking at a lake and grabbed me. Because I wore a shroud of darkness and he wanted desperately to understand what that was like. I was charmed for a while. Charmed that someone so gifted was interested in me. I thought that by being with him, his talent would rub off on me.

I was always waiting to see what he would do next. How he would handle the waitress who spilled an entire dish of pumpkin curry on his pants (he took his pants off and ate his meal in boxers); or what he would say to the fan who tracked him down and showed up at his door while we were having sex (he signed her book half leaning out the door with his hair ruffled and a sheet wrapped around his waist). He taught me how to write by simply existing—and existing well. I can’t say for sure when it was that I fell in love with him. It might have been when he told me that I had a mud vein. It might have been days later when I realized it was true. But whatever moment it took for my heart to decide to love him, it decided swiftly, and it decided for me.

God knows I didn’t want to be in love. It was cliché—men and women and their social conformities to celebrate love. Engagement pictures made me want to vomit—especially when they were taken on railroad tracks. I always pictured Thomas the Train rolling over them, his smiley blue face beaded with their blood. I didn’t want to want those things. Love was good enough, without the three-layered almond/fondant wedding cake and the sparkly blood diamonds encased in white gold. Just love. And I loved Nick. Hard.

Nick loved wedding cake. He told me so. He also told me that he’d like for us to have one someday. In that moment, my heart rate slowed, my eyes glazed and I saw my entire life flash before my eyes. It was pretty—because it was with Nick. But I hated it. It made me angry that he’d expect me to live that way. The way normal people lived.

“I don’t want to get married,” I told him, trying to control my voice. We used to have this game we’d play. As soon as we’d see each other, we’d dialogue the physical description of what the other person looked like. It was a writer’s game. He’d always start with, button nose, limpid eyes, full lips, freckles.

Now he was looking at me like he’d never seen me before. “Well, what do you want to do then?”

We were sitting on our knees in front of his coffee table, sipping warm sake and eating lo mein with our fingers.

“I want to eat with you, and fuck and see things that are beautiful.”

“Why can’t we do that after the wedding?” he asked. He licked each of his fingers and then mine, and leaned back against the couch.

“Because I respect love too much to get married.”

“That’s bitter.”

I stared at him. Was he kidding?

“I don’t think I’m bitter just because I don’t want the same things you want.”

“We can come to a compromise. Be like Persephone and Hades,” he said.

I laughed. Too much sake. “You’re not brooding enough to be Hades, and unlike Persephone, I don’t have a mother.”

My mouth clamped shut and I started sweating. Nick’s head immediately tilted to the right. I wiped my mouth with a napkin and stood up, grabbing the containers of food and carrying them to the kitchen. He followed me in there. I wanted to kick him off my heels. Nick’s mother was still married to his father. Thirty-five years. And from what I’d seen they were happy, uncomplicated years. Nick was so well balanced it was ridiculous.

“Is she dead?”

He had to ask twice.

“To me.”

“Where is she?”

“Off being selfish somewhere.”

“Aha,” he said. “Do you want dessert?”

And that’s what I liked about Nick. He was only interested in what you were interested in. And I was not interested in my past. He liked that I was dark, but he didn’t know why. And he didn’t ask. He definitely didn’t understand. But for all of our differences he took me as I was. I needed that.

Until he didn’t. Until he said that I was an emotional fort. Until nothing about me came easy, and he grew tired of trying. Nick and his words. Nick and his promises of never-ending love. I believed them all and then he left me. Love comes slow, but God does it go fast. He was beautiful—then he was ugly. I esteemed him, then I esteemed him not.

Dr. Saphira Elgin had tried to teach me to control my anger. She wanted me to be able to pinpoint the source of it so I could rationalize my feelings. Talk myself down. I can never pinpoint the source. It runs around and around in my body without a point of origin.

I blew her off. I always blew her off. But now I try to pinpoint it. I’m angry because…

Isaac is touch, and he is sound. He is smell and he is sight. I tried to make him a single sense like I did with everyone else, but he is all of them. He overpowers my senses and that is exactly why I ran from him. I was afraid of feeling brightly—afraid I would become used to the color and sounds and smells, and they would be taken from me. I was a self-fulfilling prophecy; destroying before I could be destroyed. I wrote about women like that, I didn’t realize I was one. For years I believed that Nick left me because I failed him. I couldn’t be what he needed because I was empty and shallow. That’s what he insinuated.

“Why can’t you love wedding cake, Brenna?”

“Why can’t I take your darkness away?”

“Why can’t you be who I need?”

But, I didn’t fail Nick. He failed me. Love sticks, and it stays and it braves the bullshit. Like Isaac did. And I am mad at Isaac because he is all of that. And I am all of this. It’s irrational.

Chapter Thirty-Three

We finish our project—the page project, as we call it. In the end we have four piles and only three books: Mine, Nick’s, and the nameless book. The fourth pile is the thickest and the most confusing. I stack each one with care that is mostly habit, lining up the corners until none of the pages poke past each other. The problem is, there is nothing on the pages. Each one is bone white. I have the fleeting thought that the zookeeper wants me to write a new book, then Yul Brenner reminds me that my personal Annie Wilkes didn’t leave me a pen. Can’t write a book without a pen. I wonder if I can resuscitate the old Bic we used when we first woke up here.

It must be symbolic, like the pictures hung all over the house—pictures of hollow sparrows, and bearers of death. I stare at the piles of paper while Isaac makes us tea. I can hear the tinkle of the spoon as it hits the sides of the ceramic cup. I murmur something to the books spread out around me, my lips moving in incantation. We may have separated them, but without page numbers they are still out of order. How do you bring order to a book you’ve never read? Or maybe that’s point of this little exercise. Maybe I’m supposed to bring my own personal order to the two books I’ve never read. Either way, I’m telling them to sort themselves out and speak to me. Voices have been, and always will be, too afraid to speak with as much volume as a book. That’s why writers write—to say things loudly with ink. To give feet to thoughts; to make quiet, still feelings loudly heard. In these pages are thoughts that the zookeeper wants me to hear. I don’t know why, and I don’t care except to get out of here. To get Isaac out of here.

“Do you want to have children?” he asks me when he carries our tea into the room. I am startled by the randomness of his question. We don’t talk about normal things. Our conversations are about survival. My hand trembles when I take the cup. Who could think about children at a time like this? Two pals just sitting around, chatting about their life expectations? I want to rip open my shirt and remind him that he cut off my breasts. Remind him that we are prisoners. People in our predicament didn’t talk about the possibility of children. But still … because it is Isaac who asks me, and because he has given so much, I let my mind rove over what he’s saying.

I once saw a toddler throw a fit at Heathrow Airport. Her older sister confiscated an iPhone from the little girl’s hands when she threatened to send it flying across the floor. As with most children, the tiny girl, who teetered on fresh, newly-walking legs, had a loud, indignant response. She wailed, dropped to her knees and made an awful herky-jerky noise that sounded like an ambulance siren. It rose and fell in crescendo, causing people to look and wince. As she wailed, she slid backwards on the ground until she was lying face up, her knees bent underneath her. I watched in astonishment as her arms flailed about, alternating between what looked like the backstroke and an interpretive butterfly dance. Her face was pressed into an anguished scowl, her mouth still sending out those godawful noises, when all of a sudden she scrambled to her feet, and ran laughing toward a fountain a few yards away.

As far as I was concerned children had bipolar disorder. They were angry, unpredictable, emotional ambulance-sirens with pigtails, grubby hands and food-crusted mouths that twisted from smiles to frowns and back again as quick as a breath. No, thank you very much. If I wanted a three-foot warlord as my master, I’d hire a rabid monkey to do the job.

“No,” I say.

He takes a long sip. Nods. “I didn’t think so.”

I wait for him to tell me why he asked, but he doesn’t. After a few minutes it clicks together—snap, snap, snap—and I feel sick. Isaac hasn’t been eating. He hasn’t been sleeping. He hasn’t been speaking much. I’ve watched him deteriorate slowly over the last week, coming alive only for the delivery of the white box. I suddenly feel less angry about his out-of-place question. More concerned.

“How long have we been here?” I ask.

“Nine months.”

My Rubik’s cube brain twists. More of my anger dissipates.

When we first woke up here he told me that Daphne was eight weeks pregnant.

“She carried to term,” I say, firmly. I search my brain for something else he needs to hear. “You have a healthy baby and it comforts her to have a part of you with her.”

I don’t know if this comforts him, but it’s all I know how to say.

He doesn’t move or acknowledge my words. He’s suffering. I stand up wobbling slightly. I have to do something. I have to feed him. Like he fed me when I was suffering. I linger in the doorway, watching the slight rise and fall of his shoulders as he breathes.

This is my fault. Isaac shouldn’t be here. I’ve ruined his life. I never read Nick’s book. Just those few chapters that Isaac read to me while sitting on the edge of my hospital bed. I didn’t want to see how the story ended. That’s why I swallowed it. But, now I do. I suddenly have the urge to know how Nick ended our story. What he had to say about the way things between us dissolved. It was his story that compelled me to write an answer, and get myself imprisoned in the middle of the fucking South Pole. With my doctor. Who shouldn’t be here.

I make dinner. It’s difficult to focus on anything other than the gift that the zookeeper left for me, but Isaac’s hurt outweighs my obsession. I open three cans of vegetables, and boil pasta shaped like bow ties. I mix them together, adding a little canned chicken broth. I carry the plates to the living room. We can’t eat at the table anymore, so we eat here. I call up to Isaac. He comes down a minute later, but he only pushes the food around on his plate, stabbing a different vegetable on each prong of his fork. Is this what he felt when he watched me slip into darkness? I want to open his mouth and pour the food down his throat. Make him live. Eat, Isaac. I mentally plead. But he doesn’t.

I save his plate of food, setting it in the fridge, which doesn’t quite work since he stripped off the rubber sealant to make a pedal for his drums.

I hobble up to the carousel room using my new crutch. The room smells musty and there is a faint sweet smell of piss. I eye the black horse. The one who shares my pierced heart. He looks meaner today. I lean into him, resting my head against his neck. I touch his mane lightly. Then my hand goes to the arrow. I grip it in a fist, wishing I could break it off and end both of our suffering. More than that—wishing I could end Isaac’s.

My eyelids flutter as my brain trills. When did I decide that the zookeeper was a man? It doesn’t fit. My publishing company has done research on my reader base, and it consists mostly of women in their thirties and forties. I have male readers. I get e-mails from them, but to go this far … I should see a woman. But I don’t. I see a man. Either way, I’m in his head. He’s just a character to me; someone I can’t really see, but I can see how his mind works by the way he’s playing games with me. And the longer I’m here, the more he’s taking form. This is my job; this is what I’m good at. If I can figure out his plot, I can outsmart him. Get Isaac out of here. He needs to meet his baby.

I return to the books. Eye each one. My hand lingers over Knotted briefly, before settling on the unnamed pile. I’ll start right here.