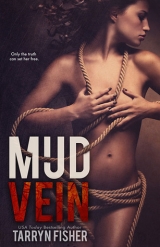

Текст книги "Mud Vein"

Автор книги: Tarryn Fisher

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

Chapter Fifteen

Isaac drove me to the hospital the next day. It was only my third time leaving the house and the thought of going back there made me sick to my stomach. I couldn’t eat the eggs or drink the coffee he put in front of me. He didn’t push me to eat like most people would, or give me the concerned eyes that most people would. It was all matter of fact; if you don’t want to eat—don’t. The moment you are diagnosed with cancer a gavel comes down on life, you start being afraid. And since I was already afraid, it felt compounded; fear pressing against fear. And just like that you inherit a cancer gremlin. I imagined it looked mutated, like my genes. It was sinister. Lurking. It kept you awake at night, gnawing on your insides, turning your mind into a distillery of fear. Fear trumps good sense. I wasn’t ready to go back to the hospital; it was the last place I was really afraid, but I had to because cancer was eating at my body.

The tests and scans started around noon. My first consult was with Dr. Akela, an oncologist Isaac went to medical school with. She was Polynesian and so strikingly beautiful my mouth hung open when she walked in. I could smell fruit on her skin; it reminded me of the bowl Isaac kept filling on my counter. I expelled the smell from my nostrils and breathed through my mouth. She spoke about chemotherapy. Her eyes had a heart and I was under the impression that she was an oncologist because she cared. I hated people who cared. They were prying and nosy and made me feel less human because I didn’t care.

After Dr. Akela, I saw a radiation oncologist, and then a plastic surgeon who pressured me to make an appointment to see a grief counselor. I saw Isaac in between each appointment, each scan. He was on his rounds, but he came to walk me to my next appointment. It was awkward. Though each time his white coat emerged, I became a little more familiar with him. It was a weird form of brand recognition—Isaac the Good. His hair was brown, his eyes were deep-set, the bridge of his nose was wide and crooked, but the most telling part of him was his shoulders. They moved first, then the rest of his body followed.

I had a tumor on my right breast. Stage II cancer. I was a candidate for a lumpectomy with radiation.

Isaac found me in the cafeteria sipping on a cup of coffee, staring out the window. He slid into the chair across from me and watched me watch the rain.

“Where is your family, Senna?”

Such a hard question.

“I have a father in Texas, but we’re not close.”

“Friends?”

I looked at him. Was he kidding? He had spent every night for a month in my house and my telephone hadn’t rung once.

“I don’t have any.” I left off the haven’t you figured that out yet? bit.

Dr. Asterholder shifted in his seat like the topic made him uncomfortable, and then, as an afterthought, folded his hands over the crumbs on the tabletop.

“You’re going to need a support system. You can’t do this alone.”

“Well what would you suggest I do? Import a family?”

He continued as if he hadn’t heard me. “There might be more than one surgery. Sometimes, even after radiation and chemotherapy, the cancer comes back…”

“I’m having a double mastectomy. It’s not going to come back.”

I wrote about shock on people’s faces: shock when they find out their love has been cheating on them, shock when they discover faked amnesia—heck, I even wrote about a character who constantly wore a look of shock on his face, even when there was nothing to be shocked about. But I couldn’t say that I’d ever seen true shock before. And here it was, written all over Isaac Asterholder. He dove in immediately, his eyebrows drawing together. “Senna, you don’t—”

I waved him off.

“I have to. I can’t live every day in fear, knowing it might come back. This is the only way.” He searched my face, and I knew then that he was the type of man who always considered what someone else was feeling. After a while the tension left his shoulders. He lifted his hands from where they’d been resting on the table, and placed them over mine. I could see the crumbs sticking to his skin. I focused on them so I wouldn’t pull away. He nodded.

“I can recommend—”

I cut him off for the third time, jerking my hands out from beneath his. “I want you to do the surgery.”

He leaned back, put both hands behind his head and stared at me.

“You’re an oncologic surgeon. I Googled you.”

“Why didn’t you just ask?”

“Because I don’t do that. Asking questions is at the forefront of developing relationships.”

He cocked his head. “What’s wrong with developing relationships?”

“When you get raped, and when you get breast cancer, you have to tell people about it. And then they look at you with sad eyes. Except they’re not really seeing you, they’re seeing your rape or your breast cancer. And I’d rather not be looked at if all people are seeing are the things I do, or the things that happen to me instead of who I am.”

He was quiet for a long time.

“What about before those things happened to you?”

I stared at him. Maybe a little too fiercely, but I didn’t care. If this man wanted to show up in my life, and put his hands over mine, and ask why I didn’t have a best friend—he was going to get it. The full version.

“If there was a God,” I said, “I’d say with confidence that he hates me. Because my life is the sum of bad things. The more people you let in, the more bad you let in.”

“Well, there you have it,” Isaac said. His eyes weren’t wide; there was no more shock. He was a cucumber.

It was the most I’d ever said to him. It was probably the most I’d said to any person in a long time. I pulled my cup up to my mouth and closed my eyes.

“All right,” he said, finally. “I’ll do the surgery on one condition.”

“What’s that?”

“You see a counselor.”

I started shaking my head before the words were out of his mouth.

“I’ve seen a psychiatrist before. I’m not into it.”

“I’m not talking about medicating yourself,” he said. “You need to talk about what happened. A therapist—it’s very different.”

“I don’t need to see a shrink,” I said. “I’m fine. I’m dealing.” The idea of counseling petrified me; all of your inner thoughts put in a glass box, to be seen by someone who spent years studying how to properly judge thoughts. How was that okay? There was something perverse about the process and the people who chose to do it for a living. Like a man being a gynecologist. What’s in this for you, you freak?

Isaac leaned forward until he was uncomfortably close to my face and I could see his irises, pure grey without any flecks or color variations. “You have Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. You were just diagnosed with breast cancer. You. Are. Not. Okay.” He pushed away from the table and stood up. I opened my mouth to deny it, but I sighed instead, watching his white coat disappear through the cafeteria doors.

He was wrong.

My eyes found the scar from the night I cut myself. It was pink, the skin around it tight and shiny. He hadn’t said anything when he found me bleeding, hadn’t asked me how or why. He had simply fixed it. I stood up and walked in his wake. If someone was going to be digging around in my chest with a scalpel, I wanted it to be the guy who showed up and fixed things.

He was standing at the main entrance to the hospital when I found him, hands tucked into his pockets. He waited until I reached him and we walked in silence to his car. We were far enough apart that we couldn’t touch, close enough together that it was clear we were together. I slid quietly into the front seat, folding my hands in my lap and staring out the window until he pulled into my driveway. I was about to get out—halfway suspended between car and driveway—when he put his hand on my arm. My eyebrows were drawn together. I could almost feel them touching. I knew what he wanted. He wanted me to promise I’d see a counselor.

“Fine.” I yanked myself out of his reach and stalked toward my house. I had the key in the lock, but my hands were shaking so badly I couldn’t turn it. Isaac came up behind me and put his hand over mine. His skin was warm like it had been sitting in the sun all day. I watched in mild fascination as he used both of our hands to turn the key. When the door swung open, I stood frozen on the spot, with my back toward him.

“I’m gonna go home tonight,” he said. He was so close I could feel his breath moving tendrils of my hair. “Will you be all right?”

I nodded.

“Call me if you need me.”

I nodded again.

I climbed the stairs to my bedroom and crawled into bed fully clothed. I was so tired. I wanted to sleep while I could still feel him on my hand. Maybe, I wouldn’t dream.

Chapter Sixteen

The next morning it was snowing. A freak February snow that coated the trees and rooftops in my neighborhood with a butter cream frosting. I wandered from room to room, standing at the windows and staring out at the different views. Around noon, when I was tired of looking, and felt the slow thrumming of a headache starting behind my temples, I talked myself into going outside. It’ll be good for you. You need the fresh air. Daylight doesn’t have teeth. I wanted to touch the snow, hold it in my hand until it burned. Maybe it could clean me of the last few months.

I walked past where my jacket hung on the coat rack and swung open the front door. The cold air hit my legs and crawled under my t-shirt. The t-shirt was all I was wearing. No layers of sweaters, no tights underneath sweatpants. The thin beige t-shirt hung around me like a shedding second skin. I was barefoot as I stepped into the snow. It gave under my feet with a soft sigh as I took a few steps forward. My father would have freaked out if he saw me. My father who yelled at me to put my slippers on if I walked on the kitchen floor barefoot in the winter. I could see tire marks that led up one side of my horseshoe driveway to where Isaac parked. It could have been the mailman. I looked back over my shoulder to see if there was a package on my doorstep. There was none. It was Isaac. He was here. Why?

I walked to the middle of the driveway and scooped up some of the snow, cupping it in my palm, looking around. It was then that I saw it. A patch of snow had been cleared from my car’s windshield. The car that I never park in the garage, though now I wish I had. There was something underneath my wiper blade. I carried my handful of snow over, stopping when I reached the driver’s side door. Anyone could drive past my house and see me half undressed, cupping snow in my hand and staring limpidly at my snow-capped Volvo. There was a brown square underneath the blade. I dropped my snow, and it landed in a semi-hard clump on my foot. The package was thin, wrapped grocery bag paper I turned it over in my hands. He’d written something on it in blue sharpie. His handwriting flicked across the paper in messy, carefree lines. A doctor’s scrawl, the kind you might find on a medical chart or a script. I narrowed my eyes, absently licking off drops of snow on the back of my hand.

Words. That’s what he’d written.

I carried it inside, flipping it over in my hand. There was a slot on one side of the cardboard. I stuck my finger inside and pulled out a CD. It was black. A generic disk, something he’d burned himself.

Curious, I put the disk into my stereo and hit play with my big toe as I stretched out on the floor.

Music. I closed my eyes.

Heavy drum beat, a woman’s words … her voice bothered me. It was emotive, going from warm cooing to hard with each word. I didn’t like it. It was too unstable, unpredictable. It was bipolar. I stood up to turn it off. If this was Isaac’s attempt at facilitating me into his music, he was going to have to try for something less…

The words—they suddenly picked me up and held me, dangling in the air; I could kick and writhe and I wouldn’t have been able to come down from them. I listened, staring at the fire, and then I listened with my eyes closed. When it was over, I played it again and listened for what he was trying to convey.

When I ripped the CD from the player and stuffed it back in its envelope my hands were shaking. I marched it to the kitchen and shoved it in the back of my junk drawer, underneath the Neiman Marcus catalog and pile of bills bound by a rubber band. I was agitated. My hands couldn’t stop moving– through my skunk streak, into my pockets, pulling on my bottom lip. I needed a detox so I retreated to my office to soak up the colorless solitude. I lay on the floor and stared up at the ceiling. Normally the white cleansed me, calmed me, but today the words to the song found me. I’ll write! I thought. I stood up and moved to my desk. But even when the blank Word document was pulled up in front of me—clean and white—I couldn’t splash any thoughts onto it. I sat at my desk and stared at the cursor. It seemed impatient as it blinked at me, waiting for me to find the words. The only words I could hear were the words of the song that Isaac Asterholder left on my windshield. They invaded my white thinking space until I slammed shut my computer and marched back downstairs to the drawer. I dug out the cardboard sleeve from where I’d shoved it underneath the catalogs and bills, and dropped it into the trash.

I needed something to distract myself. When I looked around, the first thing I saw was the fridge. I made a sandwich with the bread and the cold cuts Isaac kept stocked in my vegetable bin, and ate it sitting cross-legged on my kitchen counter. For all of his save the earth with hybrids and recycling bullshit, he was a soda fanatic. There were five variations of carbonated, stomach-eating, sugar-infested soda in my fridge. I grabbed the red can and popped the tab. I drank the whole thing watching the snow fall. Then I dug the CD from the trash. I listened to it ten times … twenty? I lost count.

When Isaac walked through the door sometime after eight, I was draped in a blanket in front of the fire, my arms wrapped around my legs. My bare feet were tapping to the music. He stopped dead in his tracks and stared at me. I wouldn’t look at him, so I kept to the fire, focused. He moved to the kitchen. I heard him cleaning up my sandwich mess. After a while he came in with two mugs and handed me one. Coffee.

“You ate today.” He sat down on the floor and leaned his back against the sofa. He could have sat on the couch, but he sat on the floor with me. With me.

I shrugged. “Yeah.”

He kept staring at me and I squirmed, pressed down by his silver eyes. Then, what he said hit me. I hadn’t fed myself since it happened. I would have starved if not for Isaac. That sandwich was the first time I’d taken action to live. The significance felt both dark and light.

We sat in silence drinking our coffee, listening to the words he left me.

“Who is it?” I asked softly. Humbly. “Who is singing?”

“Her name is Florence Welch.”

“And the name of the song?” I sneaked a glance at his face. He was nodding slightly, like he approved of me asking.

“Landscape.”

I had a thousand words, but I held them tightly in my throat. I wasn’t good at saying. I was good at writing. I played with the corner of my blanket. Just ask him how he knew.

I squeezed my eyes shut. It was so hard. Isaac took my mug and stood up to carry them to the kitchen. He was almost there when I called out.

“Isaac?”

He looked at me over his shoulder, his eyebrows up.

“Thanks … for the coffee.”

He tucked his lips in and nodded. We both knew that was not what I was going to say.

I put my head between my knees and listened to Landscape.

Chapter Seventeen

Saphira Elgin. What kind of shrink goes by the name Saphira? It’s a stripper’s name. One with scabby track marks up her arm and greasy black roots growing inch-deep above brittle yellow hair. Saphira Elgin the MD has smooth slender arms, the color of caramel. The only things decorating them were thick gold bracelets that stacked from her wrist to the middle of her forearm. It was a classy show of wealth. I watched her write something on her notepad, the bracelets tinkling gently as her pen scratched across the paper. I categorized people by whichever one of the four senses they exhibited the strongest. Saphira Elgin would fall under sound. Her office made sounds, too. There was a fire to the left of us, snapping as it ate a log. A small water fountain behind her left shoulder trickled water down miniature rocks. And in the corner of the room, past the walnut bookcase and chocolate couches, there was a large, brass birdcage facing the window. Five rainbow finches hopped and chirped from tier to tier. Dr. Elgin looked up at me from her notepad and said something. Her lips were the color of beets and I watched them vapidly when she spoke.

“I’m sorry. What did you say?”

She smiled and repeated the question. Smoky voice. She had an accent that put heavy emphasis on her ‘r’s’. It sounded like she was purring.

“Yourrr motherrr.”

“What does my mother have to do with my cancer?”

Saphira’s leg bounced gently on her knee, making a swishing sound. I’d decided to call her Saphira rather than Dr. Elgin. That way I could pretend I wasn’t being psychoanalyzed by Isaac’s choice of shrink.

“Our sessions, Senna, arrrre not just about your cancerrrr. There is morrrrre to your composition as a perrrrson than a disease.”

Yes, a rape. A parent who left me. A parent who pretended he didn’t have a daughter. A slew of bad relationships. A lost relationship…

“Fine. My mother not only walked out on her family, she also probably passed this disease down to me. I hate her for both.”

Her face was impassive.

“Has she trrrried to contact you afterrrr she left?”

“Once. After my last book published. She sent me an e-mail. Asked to meet with me.”

“And? How did you respond?”

“I didn’t. I’m not interested. Forgiveness is for Buddhists.”

“What are you then?” she asked.

“An anarchist.”

She considered me for a moment, and then said, “Tell me about your father.” Tell me about yourrrr fatherrrr.

“No.”

Her pen scratched on her notepad. It sounded itchy. Or maybe I was just aggravated.

I imagined her writing; Will not talk about father. Abuse? There was no abuse. Just nothingness.

“Your book, then.” She reached under her notepad and pulled out a copy of my last novel, setting it on the table between us. I should have been surprised that she had a copy, but I wasn’t. When it was made into a movie, I didn’t think I would see it, but I did. Chances were they’d turn my book into some bastardized Hollywood knockoff. At least my book would get good publicity. They anticipated a small release, but on opening night the movie grossed three times the expected amount and then went on to top the box office for three weeks before it was knocked out by a tights-wearing superhero. My book became an overnight sensation. And I hated it. All of a sudden everyone was looking at me, looking into my life, asking questions about my art, which I had always deemed highly private. So, I bought a house with my money, changed my number and stopped answering my e-mails. For a while I was one of the most sought after interviews in the book world. Now I was a rape victim and I had cancer.

I hated Isaac for making me do this. I hated him for making this the condition for performing my surgery. I’d taken to the internet, searching other surgeons who could cut out my cancer. They were plentiful. Cancer was trending. There were websites you could go to where you could see their pictures, where they went to medical school, how their former patients rated them. Five stars to Dr. Stetterson from Berkley! He took the time to know me as a person before dissecting me like a live specimen! Four stars to Dr. Maysfield. His bedside manner was stiff, but my cancer is gone. It was like a damn dating site. Scary. I’d quickly closed the window and resolved to see the shrink Isaac was forcing on me.

The only peace I had at that point was knowing it was he who would cut the cancer from my body. Not any old stranger—the stranger who’d been sleeping on my couch and feeding me.

“Let’s talk about your last relationship,” Saphira said.

“Why? Why do we have to dissect my past? I hate it.”

“To know who a person really is, I believe you have to know first who they were.”

I hated where she put her words. A normal person would have said you first have to know who they were. Saphira mixed everything up. Threw me off. Used her dragged out ‘r’s’ as a weapon. She was a purring dragon.

In my hesitation, her pen scratched on paper again.

“His name was Nick.” I picked up my untouched coffee and spun the cup in my hands. “We were together for two years. He’s a novelist. We met at a park. We broke up because he wanted to get married and I didn’t.” Some of the truth. It was like sprinkling artificial sweetener over bitter fruit.

I sat back, satisfied that I’d filled the session with enough information to keep Saphira the Dragon happy. She raised her eyebrows, which I figured was the prompt to keep talking.

“That’s it,” I snapped “I’m fine. He’s fine. Life moved on.” I pulled out my grey and smoothed it back behind my ear.

“Where is Nick now?” she asked. “Do you keep in contact?”

I shook my head. “We tried that for a while. It was too painful.”

“For you, or him?”

I stared at her blankly. Weren’t breakups always painful for everyone involved? Maybe not…

“He moved to San Francisco after he published his last book. Last I heard he was living with someone.” I looked at the finches while she wrote on her notepad. I had to turn my back to her to do it, but it felt good, like passive-aggressive defiance.

“Did you read his book?”

I waited a second to turn back around, just enough time to rearrange my face. I lifted a hand to my throat, wrapping my forefinger and thumb under my chin. Nick used to say it looked like I was trying to strangle myself. I suppose subconsciously I was. I quickly pulled my hand away.

“He wrote it about me … about us.”

I had thought that would be enough, that it would divert her attention and allow me to breathe. But she waited patiently for my answer. Did you read his book? Her chocolate eyes were unblinking.

“No, I didn’t read it.”

“Why not?”

“Because I can’t,” I snapped. “I don’t want to read about how I failed him and broke his heart.”

It felt okay to say. The problems I had two years ago with Nick felt welcome compared to what was lurking in the shallow tide pools of my memory.

“He mailed me a copy. It’s been sitting on my nightstand for two years.”

I glanced at the clock … hoping. And, yes! Our time was up. I jumped up and grabbed my purse.

“I hate this,” I said. “But my stupid surgeon won’t operate unless I talk to you.”

She nodded. “I’ll see you Thursday.”

I was shrugging my coat on and opening the door when she called after me.

“Senna.”

I paused, one arm not all the way in my sleeve.

“Read the book,” she said.

I left without saying goodbye. Dr. Elgin was humming softly as the door quietly shut behind me.

It was the first time I’d driven myself anywhere. I brought Isaac’s CD, and I played Landscape all the way home. It calmed me. Why? I’d love to know. Maybe Saphira could eventually tell me. It was the only song I owned that actually had words attached to it, and the beat wasn’t particularly soothing. Quite the opposite.

When I got home, I carried the CD inside. I set it on the kitchen counter and climbed the stairs. I had no intention of listening to anything Saphira Elgin said, but when I saw the cover of Nick’s novel lying next to my bed, I picked it up. It was a reflex—we’d been talking about the book, and now I was having a look. There was a fine layer of dust over the top. I wiped it off with my sleeve and studied the jacket for clues. The cover was not his style, but authors had little say over what cover went on their book. There is a team that does that at the publishing company. They brainstorm with cheap Flavia coffee, in a windowless conference room-that’s what my agent told me at least. If I was looking for Nick in the cover, I would not find him. The cover looked like a close-up of bird feathers: greys and whites and blacks. The title is angled in chunky white letters: Knotted.

I opened it to the dedication page. That was as far as I’d gotten in the past before slamming it shut.

For MV

I breathed through my mouth, flexing my fingers across the open page like I was preparing to do something physical. My mind caressed the dedication again.

For MV

I turned the page.

Chapter One

She bought me with words; beautiful, promising and intricately carved words…

My doorbell rang. I closed the book, set it on my nightstand, and went downstairs. There was no way in hell I was reading that.

“We should just make you a key,” I said to Isaac. He was standing on my doorstep, arms loaded with paper grocery bags. I stepped aside to let him in. It was a snarky comment, but I’d said it with familiarity.

“I can’t stay,” he said, setting the bags down on the kitchen counter. There was a brief sting, like a bee had wandered into my chest cavity. I wanted to ask him why, but of course I didn’t. It wasn’t my business where he went or who he went there with.

“You don’t have to do this anymore,” I said. “I saw Dr. Elgin today. Drove there myself. I—I’m better.”

He was wearing a brown leather jacket and his face was scruffy. It didn’t look like he came from the hospital. And on days he did there was always the faint smell of antiseptic around him. Today there was only aftershave. He rubbed his fingers across the hair on his face. “I scheduled your surgery for two weeks from Monday. That way you’ll have a few more sessions with Dr. Elgin.”

My first instinct was to reach a hand up to feel my breasts. I’d never been one of those women who prided themselves on their bra size. I had breasts. For the most part I ignored them. But, now that they were going to be taken, I felt protective.

I nodded.

“I’d like you to keep seeing her … after…” His voice dropped off, and I looked away.

“All right.” But I didn’t mean it.

He tapped the granite with his fingertip. “All right,” he repeated. “I’ll see you later, Senna.”

I started unpacking the groceries. At first I felt nothing. Just boxes of pasta and bags of fruit being shelved … put away. Then I felt something. An itch. It nagged at me, tugging and pulling until I was so frustrated I threw a box of soup crackers across the room. They hit the wall and I stared at the spot where they’d landed, trying to find the sound of my emotion. Sound. I ran to the living room and hit play on Florence Welch. She’d been singing this song to me nonstop for days. Her real voice would be tired by now, but her recorded voice called out to me, unfailing. Strong.

How had he known this song, these words, this tormented voice would speak to me?

I hated him.

I hated him.

I hated him.