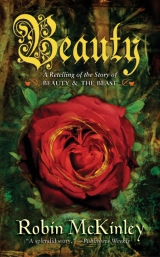

Текст книги "Beauty"

Автор книги: Robin McKinley

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 13 страниц)

At supper I was silent, as I had been for most of the day. The Beast had asked me several times if I was unwell, if there was something troubling me; I had put him off each time with a few brusque or impertinent words. Each time he looked away and forbore to press me. I felt guilty for the way I treated him; but how could I tell him what was hurting me? I had agreed to come and live in his castle to save my father’s life, and I must abide by my promise. The Beast’s subsequent kindness to me led me to hope that one day he might set me free; but I did not think I could rightfully ask. At least not yet, after only four months. But I longed so much to see my family that I could only remember to hold to my promise; I could not always do it cheerfully.

I was staring into my teacup when the Beast asked me once more: “Beauty. Please. Tell me what is wrong. Perhaps I can help.”

I looked up, irritated, my mouth open to tell him to leave me alone—please: But something in his expression stopped me. I flushed, ashamed of myself, and looked down again.

“Beauty,” repeated the Beast.

“I—I miss my family,” I muttered.

The Beast leaned back in his chair and there was a pause. “You would leave me then?” he said; and the hopelessness m his voice shook me even from the depths of my self-pity. I remembered for the first time since my home-sickness had seized me the night before that he had no family to wish for. “It is rather lonesome here sometimes,” he had said at our first meeting; and I had been able to pity him then, before I had learned to like him. My friendship was worth little if I could forget it, and him, so quickly.

“I would be very sorry never to see you anymore,” I said. “But you have been so kind to me that I have—I have occasionally wondered perhaps if—perhaps if after some term is completed, that you would—might let me go. I would still wish to remain your friend.” He was silent, and I went falteringly on: “I know it is too soon yet—I have only been here a few months. I know I shouldn’t have mentioned it. It is very ungrateful of me—and dishonourable,” I said miserably. “I didn’t want to say anything—I wasn’t going to—but you kept asking what was wrong—and I miss them so very much,” and I caught myself up on a sob.

“I cannot let you go,” said the Beast. I looked at him. “Beauty, I’m sorry.” He seemed about to say something more, but I gave him no time.

“Cannot?” I breathed. There was something interminable in that short word. I stood up and backed a few steps away from the table. The Beast sat, with his right hand on the table, the white bandage on it almost covered by the waves of lace. He looked at me; I could not

see his eyes; the world was turning a shimmering, dancing grey, like the inside of a snowflake. I blinked, and a voice I did not recognize as my own said: “Never let me go? Not ever? I will spend my entire life here—and never see anyone again?” And I thought: My life? He has been here two centuries. What is my life span likely to be here? The castle was a prison; The door would not open. “Dear God,” I cried, “the door won’t open. Let me out, let me out!” I raised my fists to pound on silent wooden panels that I seemed to see loom up in front of me, and then I knew no more.

I returned to consciousness slowly and piecemeal. For the first few minutes I had no idea where I was; at first I supposed that I was at home, in bed. But that could not be; the pillow under my cheek was soft and slightly furry—velvet, I thought drowsily. Velvet. We have no velvet at home—except what the Beast sent in Father’s saddlebags. The Beast. Of course, I was in the castle. I had been here for several months. Then I remembered, still dimly, that very recently I had been terribly unhappy; but I did not remember why. How could I be unhappy here? I thought. I have everything I want, and the Beast is very kind to me. A stray thought, less substantial than a wisp of smoke, suggested, The Beast loves me; but it dissolved immediately and I forgot about it. Just now I was very comfortable, and I did not want to move. I rubbed my cheek a little against the warm velvet. There was a curious odour to it; it reminded me of forests, of pine sap and moss and springwater, only with a wilder tang beneath it.

My memory began to return. I had been unhappy because I was home-sick. The Beast had said that he could not let me go home. Then I must have fainted. It occurred to me that the velvet my face rested on was heaving and subsiding gently, like someone breathing; and my fingers were wrapped around something that felt very much like the front of a coat. There was a weight across my shoulders that might have been an arm. I was leaning against the whatever-it-was, half sitting up. I turned my head a few inches, and caught a glimpse of lace, and beneath it a white bandage on a dark hand; and the rest of my mind and memory returned with a shock like a snowstorm through a window blown suddenly open.

I gasped, half a shriek, let go the velvet folds I was clutching, and pushed myself violently away. I found myself kneeling at the opposite end of a small cushioned sofa. This was the first time I saw him clumsy. He stood up and took a few stumbling steps backwards; he held out his hands and looked at me as though I hated him. “You fainted,” he said; his voice was a rough whisper. “I caught you before you reached the floor. You—you might have hurt yourself. I only wanted to lay you down somewhere that you could be comfortable.” I stared at him, still kneeling, with my fingernails biting into the sofa cushions. I couldn’t look away from him, but I did not recognize what I saw. “You—you clung to me,” he said, and there was a vast depth of pleading in his voice.

I wouldn’t listen. Something inside me snapped; I put my hands over my ears, half-fell off the couch, and ran; he moved out of my way as if I were a cannon-ball or a madwoman, A door opened in front of me and I bolted through it. I had to pause to look around me; this was the great front hall. He had carried me from the dining room to the huge drawing room opposite it. I picked up my skirts and ran upstairs to my room as if Charon himself had left his river to fetch me away.

I passed another bad night, pulling my bed to pieces, unable to sleep. When I did doze, I dreamed uneasily, and several times I saw the arrogant, handsome young man of the last portrait in the gallery by the library. He seemed to look through me, and mock me; except for the last time he appeared, when he was very much older, with grey in his hair, and lines of wisdom and sympathy drawn on his handsome face; and he looked at me sorrowfully, but said no word. I rose shortly before dawn, when the black rectangle of my window began to turn grey, and I could see the leading around the individual panes. I wrapped my serf in a quilted dressing gown, a bright blue and crimson that did nothing for my bleak brown mood, and sat on the window seat to watch the sun rise. The pillows and blankets rearranged themselves in a subdued fashion, and only when I wasn’t looking at them. I felt deserted—the breeze that attended me had left after putting me to bed the night before, and did not return to keep me company during my early vigil. Often before when I had had restless nights, it would fuss around me with cups of warm milk sweetened with honey, and lap robes, if I still insisted on getting up.

But my head was clear, strangely clear, for two nights of sleeplessness and emotional upheaval; in fact I felt more clear-headed than I could ever recall feeling be—

169 ·

fore. Light-headed is more likely, I told myself severely. It’s an ill wind, though: I seem to have been cured of the worst of my home-sickness, for the moment anyway. That will probably turn out to be an illusion though, too. I’m just numb with exhaustion. Exhaustion? Shock. Shock? Well, why? What is so inherently awful about being carried to a sofa?

I had avoided touching him, or letting him touch me. At first I had eluded him from fear; but when fear departed, elusiveness remained, and developed into habit. Habit bulwarked by something else; I could not say what. The obvious answer, because he was a Beast, didn’t seem to be the right one. I considered this. I did not get very far; but I thought I knew what Persephone must have felt after she ate those pomegranate seeds; and was then surprised by a sudden rush of sympathy for the dour King of Hell.

That curious feeling of clear-headedness increased with the light. Grey gave way to pink, and then to deep flushed rose edged with gold; there wasn’t a cloud in the sky, and I could see the morning star shining like hope from the bottom of Pandora’s box. I opened a section of the window and a little wind slipped inside to play with my rumpled hair and tickle me back into the beginnings of a good mood.

Then I heard the voices. There was a rustling about them, like too many stiff satin petticoats, and I looked around in surprise, half-expecting to see someone. “Oh dear, oh dear,” said the melancholy voice. “Just look at that bed. I’m sure she hasn’t had a wink of sleep all night. Here now”—more sharply—“what are you about? Pull yourselves together immediately!” The bedclothes started scrambling over one another, and the bed-curtains quivered anxiously.

“Don’t be too hard on them,” said the practical voice mildly. “They’ve had a rough night too.”

“We all have,” said the first voice. “Oh yes indeed. And look at her sitting beside that open window, with her robe all open at the neck, and nothing but a bit of lace for a nightgown! She’ll catch her death!” I guiltily put a hand to my collar. “And her hair! Good heavens. Has she been standing on her head?”

The voices—these were the voices I had heard several times, just before I had drifted into sleep or just after; I had never decided which. They were my invisible maidservants, my friendly breeze, the voices of plain common sense in this magic-ridden castle. They whisked around now, finding hot water in a fold in the air, putting it in a basin, laying towels beside it. Breakfast was laid out—“It is early, but she will certainly feel better after she has eaten”—and all the while they talked, discussing me: “How pale and pinched she looks! Tonight we must be sure she rests properly”; and the coming day, and my wardrobe, and the difficulties of getting the food decently cooked and the floors decently waxed, and so on.

I sat amazed, listening. At first I thought that I must be asleep and dreaming, in spite of the cold clean touch of the dawn; that would also explain the odd sense of preternatural clear-headedness—I might dream anything.

But the sun rose, and I washed my face and hands and ate breakfast, while the voices went on and I listened. The clink of plate and fork and teacup, and the taste of the food, decided me. I was awake; something else had happened to me in this castle where anything might happen. I wondered what else I might find that I could hear or see that had been hidden from me until now.

! almost said aloud: “I can hear you”—but I stopped myself. Perhaps if I pretended continued deafness I would learn what they had meant, when I had caught bits of their conversation—for I was now sure I had heard them—in the weeks past: “You know it’s impossible.”

“It was made to be impossible.” After breakfast, when they brought me a walking dress—did I catch the shimmer of something almost visible out of the corners of my eyes, as they blew around me?—I did say, aloud, “I missed you last night.”

“Oh dear, she missed us, I knew she would, we’ve always been here before. But we couldn’t leave him; I haven’t seen him in such a temper since—oh, years and years. I’m always afraid he may do himself a mischief when he’s in that state—not that she has anything to fear—but we’ve always stood by him in such moods, it seems safer, we don’t really help anything but our presence is a distraction, I think, and anything is better than nothing at all.”

“It is very difficult for him. Much more so than for us.”

“Well, of course”—indignantly. “We’re almost—volunteers; and invisibility isn’t really so bad once you’re accustomed to not seeing yourself around, you know....”

“Yes, I know,” the other voice said drily.

“It is certainly a good thing that that magician took himself off directly after he’d finished his nasty business here, or he would have been murdered. Nights like this past remind me of it. Although I never have understood why killing a magician like that—fiend—yes, fiend—should be counted as murder; after all, he’s not even human,”

“Now, Lydia. That sort of talk will get you nowhere—and he would be angry if he heard you. If he knows better, surely we should.”

“Oh, Bessie, I know, it’s very wrong of me, but I sometimes—I just can’t help it.” The voice sounded near tears. “This can’t possibly work.”

“You may think what you like of course,” the other voice said briskly, “but I shan’t give up. And neither will he.”

“No,” said the melancholy voice, but in a tone so woebegone as to suggest that determination was only another aspect of the problem.

A Faint jingly noise like a laugh. “She’s a good girl, and bright enough. She’ll figure it out in the end.”

“The end is a very long time off,” Lydia said gloomily.

“All the more reason to be hopeful; there’s plenty of time. And she’s stronger than she knows—even if she understands nothing of it. You’ve seen the birds? They come to the garden now—and you know that that was expressly forbidden. Nothing—not even butterflies, not even birds. But we have birds now.”

“That’s true,” Lydia said wistfully.

“Well then,” said Bessie, as if the argument was won. “Now then, come along; there’s a lot to be done before lunch.” Invisible fingers patted my hair and shoulders, and the breeze whirled up and was gone.

All this made no sense to me at all. A magician? Well, if ever there was a place that was obviously under a spell, this was it. And the Beast—he must be the “he” they talked so much about. He must be under a spell too. He had said once, “I have not always been as you see me now.” And they said that I was “bright enough”: Were there clues, then, that I was supposed to be picking up, arranging into a pattern? Oh dear. I didn’t know anything about magic, and spells, and things; such branches of learning were considered a little less than respectable by everyone I knew—nor very intellectually rewarding, so I had felt little interest in them. Surely that wasn’t the method I was supposed to be looking for. But what else was there? I felt very stupid, notwithstanding Bessie’s—stubborn, it seemed to me—faith that everything would work out in the end.

I tackled something more readily accessible: “He” had been in a temper last night.

Sudden dismay clutched my stomach, and my breakfast somersaulted. Was he very angry with me then? “... Not that she has anything to fear ...” Lydia had said. Dismay and my breakfast subsided, but I was still worried; I didn’t like the idea of his being angry with me—perhaps I bad treated him badly last night. Perhaps I should apologize. What if he was so angry that I didn’t see him today? I felt lonely at once, and ashamed of myself.

I took the peacock-tin that held birdseed to the window. I leaned outside and whistled, scattering some seed on the sill as I did so. Butterflies and birds were forbidden; I was stronger than I knew, although I didn’t know why. I sighed. I certainly didn’t know why.

Little dark shadows crossed my face, and then I felt tiny feet on my head, and a sparrow perched on my outstretched hand, “Here, come down from there,” I said, gently dislodging the chaffinch sitting on my head. We discussed the weather and the possibility of rain in chirps and blinks, and I tried to lure a robin to take seed from my hand, but he only cocked his head and looked at me. No birds were allowed. Maybe these weren’t real birds at all, but figments invented by the castle, or by the Beast, because I’d wanted birds. They looked real; the prick of their tiny claws was real. There were never very many of them—whatever that meant. And it was true, too, that recently I had heard birdsongs sometimes when I was out riding Greatheart. Maybe the spell was weakening? Maybe I wouldn’t have to do anything heroic after all.

I had been sitting with the birds perhaps ten minutes when I began to feel uneasy. Uneasy was perhaps too strong a word. It was like trying to catch the echo of a sound so faint I wasn’t sure it existed. Something existed that was niggling at the edge of my consciousness. I turned my head this way and that, seeking some plainer hint. No; it wasn’t so much like a sound as like a teasing whiff of something, something that reminded me of forests, of pine sap and springwater, but with a wilder tang beneath it. The birds were still pecking unconcernedly around my fingers, along the sill.

“Beast,” I called. “You’re here—somewhere. I can feel it. Or something.” I shook my head. There was a brief vision, behind my eyes, of him gathering himself together to materialize out of my sight, around a corner of the castle, before he walked around it in normal fash—

ion and came to stand beneath my window. The birds flew away as soon as he had appeared—before he walked around the corner, and I could see him. “Good morning, Beauty,” he said.

“Something’s happened to me,” I said like a child seeking reassurance. “I don’t know what it is. I’ve felt peculiar all morning. How did I know you were near?”

He was silent.

“You know something of it,” I said, still listening to my new sixth sense.

“I can see that your new clarity of perception will create difficulties for me,” he said lightly.

My room was on the second storey, over a very tall first storey, so I was looking down more than twenty feet to the cop of his head. He had not looked up at me since he had wished me good morning. The grey in his hair seemed to reproach me for not being cleverer in understanding the spell that was laid on him, in not being of any use to him. Today he was wearing dark-red velvet, the colour of sunset and roses, and cream-coloured lace.

“Beast,” I said gently. “I—want to apologize for my behaviour last night. It was very rude of me. I know you were only trying to help.”

He looked up then, but I was too far away, even leaning down over the sill with my elbows on the edge and my hands dangling, to read any expression on that dark face. He looked down again, and there was a pause. “Thank you,” he said at last. “It’s not necessary, but—well—thank you.”

I sat farther out on the window ledge, spraying him with birdseed as he stood below. “Oh—er, sorry,” I said. His face split into a white smile, and he said, “Aren’t you coming for your walk in the garden? The sun is getting high,” and he brushed cracked corn and sunflower seeds from his shoulders.

“Of course,” I said, and slid back into my room, and was downstairs and outside in the courtyard, running towards the stable, in a moment. I let Greatheart out, and he roamed on ahead of us like an oversized dog, while the Beast and I walked behind. When the horse had found a meadow to his taste and was settled down to some serious grazing, I sat down on a low porphyry wall and looked at the Beast, who avoided my gaze.

“You know something about what’s happened to me,” I said, “and I want to know what it is.”

“I don’t know exactly,” said the Beast, looking at Greatheart. “I have some idea of it.”

I curled my feet up beside me on the wall. The Beast was still standing, hands in pockets, half turned away from me. “Well?” I said. “What’s your idea?”

“I’m afraid you won’t like it, you see,” said the Beast apologetically. He sat down at last, but kept his eyes on the horse.

“Well?” I said again.

The Beast sighed. “How shall I explain? You look at this world—my world, here, as you looked at your old world, your family’s world. This is to be expected; it was the only world, and the only way of seeing, that you knew. Weil; it’s different here. Some things go by different rules. Some of them are easy—for example, there is always fruit on the trees in the garden, the flowers never fade, you are waited on by invisible servants.” With a little tremor of laughter in his voice he added: “And many of the books in the library don’t exist. But there are many things here that your old habits and skills have left you unprepared for.” He paused, “I wondered, before you came, how you’d react—if you came. Well, I can’t blame you; you were tricked into coming here. You have no reason to trust me.”

I started to say something, in spite of not wanting to interrupt him for fear that he would not continue; but he shook his head at me and said, “Wait. No, I know, you’ve gotten used to the way I look, as much as anyone can, and my company amuses you, and you’re grateful that your imprisonment here isn’t as direful as you were anticipating—being served for dinner with an apple in your mouth, or a windowless dungeon far underground, or whatever.” I blushed and looked down at my hands. “I’ve never liked Faerie Queen,” he added irrelevantly. “It gives so many things a bad name.

“But I don’t blame you,” he continued. “As I said, you have no reason to trust me, and excellent reason not to. And in not trusting me, you trust nothing here that you cannot perceive on your old terms. You refuse to acknowledge the existence of anything that is too unusual. You don’t see it, you don’t hear it—for you it doesn’t exist.” He frowned thoughtfully. “From what you’ve told me, a little strangeness leaked through to you, your first night here, when you looked out your window. It frightened you—I quite understand this; it used to frighten me too—and you’ve avoided seeing anything else since.”

“I—I haven’t meant to,” I said, distressed at this picture of myself.

“Not consciously, perhaps; but you have resisted me with all your strength—as any sane person would, when confronted with a creature like me.” He paused again. “You know, the first drop of hope I tasted was that day I first showed you the library—when you were confronted with the works of Browning, and of Kipling, and you saw them. You might not have; you might have seen only Aeschylus and Caesar and Spenser, and authors you could have known in your old world.” He went on as if talking to himself: “Later I realized that this was only a reflection of your love and trust for books; it had nothing to do with me, or with my castle and its other wonders. And the birds came to you; that seemed a hopeful sign. But they came because of the strength of your longing for your old home. But perhaps it was a beginning nonetheless.

He was silent for so long that I thought he would say no more, and I began to consider what sort of question to put to him next. But there was a strange quality to my sight that distracted me—a new depth or roundness, which seemed to vary depending on what I was looking at. Greatheart looked as he always had, large and dapple-grey and patient and lovable. But the grass he waded through caught the sunlight strangely, and seemed to move softly in response to something other than wind. When I looked up, the forest’s black edge shivered and ran like ink on wet paper. It reminded me of the spidery quaking shadows I had seen from my window on my first night in the castle; but there was no dread to what I was, or wasn’t, seeing now. This is silly, I thought; I don’t suppose you really see the sort of thing he’s talking about. What’s wrong with my eyes? I found myself blinking and frowning if I looked steadily at the Beast, too; it wasn’t that he looked any less huge or less dark or less hairy, but there was some difference. And how do I know whether I should see the sort of thing he’s talking about or not? There was something wrong, that first night. There’s something wrong now.

“Last night,” he began again at last, “when you fainted, you were helpless, for good or ill, I carried you to a couch in the next room; I was going to call your servants, and leave you alone. But when J tried to set you down, you murmured in your sleep, and held on to my coat with both hands.” He stood up, took a few paces away from me, a few paces back. “For a few minutes you were content—even happy—that I held you in my arms. Then you remembered, and ran away in panic. But it’s those few minutes of sympathy, I think, that caused whatever change you’re noticing now.”

“Am I always going to know when you’re nearby now?” I said, a little wistfully.

“I don’t know. I should think it likely. I always know where you are, near or far. Is that all it is—dial you were aware of me when you couldn’t see me?”

I shook my head, “No. My vision is funny. My colour sense is confused somehow. And you look funny.”

“Mmm,” he said. “I shouldn’t worry about It if I were you. As I told you at our first meeting, you have nothing to fear. Would you like to go back now?”

I nodded assent and we turned and walked slowly back towards die castle. Greatheart tore up a few last hasty mouthfuls and followed. I had a great deal to ponder, and did not speak; nor did the Beast say anything.

The rest of the day passed as my days usually did. I did not again mention my new strange sense of things, and by the end of the afternoon the new crystalline quality to die air, the way the flower petals shaded off into some colour I couldn’t quite put a name to, and the way I was hearing things that weren’t strictly sounds had, by and large, ceased to disturb me. That evening’s sunset was the most magnificent that I had ever seen; I was stunned and enthralled by its heedless beauty and remained staring at the sky till the last shreds of dim pink had blown away, and the first stars were lit and hung in their appointed places. I turned away at last. “I’m sorry,” I said to the Beast, who stood a little behind me. “I’ve never seen such a sunset. It—it took my breath away.”

“I understand,” he replied.

I went upstairs to dress for dinner, still bemused by what I had just observed, and found an airy, gauzy bit of lace and silver ribbons draped across the bed and gleaming in its own pale light. A corner of the skirt lifted briefly as I entered, as though a hand had begun to raise it and then changed its mind.

“Oh for heaven’s sake,” I said in disgust, recalled from my visionary musings with a bump. “We’ve been through all this dozens of times before. I won’t wear anything like this. Take it away.” The dress was lifted by the shoulders till it hung like a small star in my chamber, and for all my certainty that I would not wear it, I did look at it a little longingly. It was very beautiful; more so, it seemed to me, than any of the other wonderful clothes my high-fashion-minded breeze had tried to put on me.

“Well?” I said sharply. “What are you waiting for?”

“This is going to be difficult,” said Lydia’s voice. If I

hadn’t been accustomed, until that day, to not hearing them, their present silence would have seemed ominous to me. Even the satin petticoats were subdued. I was suddenly uneasy, wondering what they had planned for me. The dress was wafted over to lie negligently across an open wardrobe door, and I was assisted out of my riding clothes. I was still shaking my hair loose from its net when there was a moment of confusion, like being caught in a cloud or a cobweb, and I emerged from it pushing my wild hair off my face and found that they had disobediently wrapped me in the shimmering bit of nothing I had ordered back into the closet.

“What are you doing?” I said, surprised and angry. “I won’t wear this. Take it off.” My hands searched for laces to untie, or buttons, but I could find nothing; it fitted me as if it had been sewn on—perhaps it had, “No, no,” I said. “What is this? I said no.” Shoes appeared on my feet; the golden heels were set with diamond chips, and bracelets of opals and pearls began to grow up my arms. “Stop it,” I said, really angry now. My hair twisted up, and I reached up and pulled a diamond pin out of it till it rumbled down around my shoulders and back; the pin I threw on the floor. My hair cascading down around me startled me as I realized that it was brushing bare skin. “Good heavens,” I said, shocked, looking down; there was hardly enough bodice to deserve die name. Sapphires and rubies appeared on my fingers. I pulled diem off and sent them to join the diamond hair-pin. “You shan’t get away with this,” I said between my teeth, and kicked off the shoes. I hesitated to rip the dress off; I didn’t like to damage it, angry as I was, and again I tried to find a way out of it. “This is a dress for a princess,” I said to the listening air. “Why must you be so silly?”

“Well, you are a princess,” said Lydia, and she sounded as if she were panting a little. Bessie said: “I suppose we must start somewhere, but this is very discouraging.”

“Why is she so stubborn?” asked Lydia, plaintively. “It’s a beautiful dress.”

“I don’t know,” replied Bessie, and I felt a quick surge of their determination, and this angered me even more.

“It is a beautiful dress,” I said wildly, as my hair wound up again and the pin flew back to its place, and the shoes, and the rings to theirs; “And that’s why I won’t wear it; if you put a peacock’s tail on a sparrow, he’s still a brown little, wretched little, drab little sparrow,” and as a net of moonbeams settled around my shoulders and a glittering pendant curled lovingly around my neck, I sat down in the middle of the floor and burst into tears. “All right, I don’t seem to be able to stop you,” I said between sobs, “but I will not leave the room.” I wept myself to silence and then sat, still on the floor, with my abundant skirts anyway around and under me, staring into the fire. I took the pendant off, not in any hope that it would stay off, but just to see what it was: It was a golden griffin, wings spread and big ruby eyes shining, about twice the size of the ring I wore every day and kept beside my bed at night. For some reason it made my tears flow again. My face must have been a mess, but the tears left no stain where they dropped onto the princess’s dress. I meekly refastened the griffin around my neck, and it settled comfortably into the hollow of my throat.