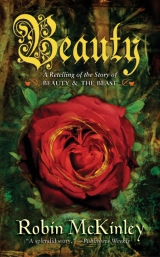

Текст книги "Beauty"

Автор книги: Robin McKinley

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 13 страниц)

“The only problem with this place is the silence,” I said conversationally to my teacup. “Even the fire burns quietly; and while I can’t fault the service”—and I wondered if there were anything to hear—“I could almost like a little more rattling of cutlery and so forth. It makes a house, or even a castle, seem lived-in.” I took my teacup over to the window. “I’ve never liked house pets much—monkeys are a nuisance, dogs shed and make me sneeze, and cats claw things—but birds, now. It would be very nice to have Orpheus here to sing to me.” I found a latch to the window, and a section of it swung out, noiselessly of course. “Not even any birds here,” I continued, leaning out. “I can see how anything that goes on feet would want to stay out of his way; but surely he doesn’t control the sky,” There was a broad window ledge with a shallow flat-bottomed trench cut into it. “Just the thing for birds,” I said, and found a tin at my elbow, with jeweled peacocks painted on it, full of mixed seeds such as a bird might like. I spread several generous handfuls of this along the ledge. “All I ask is a few sparrows,” I said. “The only peacocks I ever knew bit people.”

I looked out across the gardens. It was odd that no birds had found those trees and flowers. “Perhaps they’re only waiting to be asked,” I said. “Well, consider yourself invited,” I said loudly. “On my behalf, anyway.” I closed the window again, changed into a divided skirt more or less suitable for riding—“Haven’t you ever heard of plain clothing?” I said in exasperation, searching through the wardrobes for a blouse without ribbons or jewels or lace, while the breeze plucked protestingly at my elbows—and went out again to take Greatheart for his ride.

He was feeling lively, and once we were beyond the stately gardens with their trim paths it took very little urging to get him into his long-striding gallop. The air was cold, out beyond the gardens; I had brought a cloak, and after pulling Greatheart down to a jog, I wrapped it around me. I had expected to reach the tall holly hedge that bounded my prison fairly soon; it had not taken so very long to ride in the night before, and Father had seen the gates from the garden. But now we walked and trotted through fields, and stands of trees, and more fields, and more trees. It was wilder country here, with rocks and twisted scrub, and the ground underfoot was uneven. I wondered if perhaps the hedge did not extend all the way around the Beast’s lands, and perhaps we had re-entered the fringes of the enchanted forest. Not that that would be very useful, I thought; I’d probably just find that carriage-road again, and be led straight back. And I don’t fancy trying to find my way out till I starve to death.

There were even patches of snow where we were walking. I turned to look over my shoulder. I could still see the castle towers dark and solemn against the clear blue sky, but they were getting far away. “Time we were heading back,” I said, reined him round, and kneed him into a ponderous canter. “Back home, I suppose,” I said thoughtfully. It wouldn’t do to try to escape on my very first day anyway, I thought. Particularly since it wouldn’t do any good.

The sun was low in the sky by the time I had stabled Greatheart, groomed him, and again cleaned the tack by hand. “Yes, and I did notice that all the mended bits have been replaced, and I thank you,” I said aloud, polishing the bits. If I didn’t do it, the invisible hands would; I had also noticed that the bits and buckles had been shined to mirror hue after I’d left them a respectable glossy clean last night, and felt that I was being put on my mettle. My hands were still bandaged; they felt a little stiff, but they no longer troubled me—and the magic bandages didn’t get soiled, even after I’d soaped and oiled the leather.

I went a little way into the garden after leaving the stable and sat on a marble bench, still warm from the sun, to watch the afternoon change to evening grey and flame. Or at any rate it could be the sun that warmed it, I thought; I also took notice that the bench was just the right height for someone of my short length of leg. I turned my head to look over another sweep of the gardens, and saw the Beast coming towards me. He was already very near, and I bit back a cry; he walked as silently as the shadows crawling towards my feet, in spite of the heavy boots he wore. Today he was wearing brown velvet, the color of cloves, and there was ivory-coloured lace at his throat, and hanging low over the backs of his hands.

“Good evening, Beauty,” he said.

“Good evening, Beast,” I replied, and stood up.

“Please don’t let me disturb you,” he said humbly. “I will go away again if you prefer.”

“Oh no,” I said hastily, trying to be polite. “Will you walk a little? I love to see the sun set over a garden, and yours are so fine.” We walked in silence for a minute or two; I’ve had better ideas, I thought, taking three steps to his one, although I could see that he was adjusting his pace to mine as best he could. Presently I said, a little out of breath, but finding the silence uncomfortable: “Sunset was my favourite time of the day when we lived in the city; I used to walk in our garden there, but the walls were too .high. When the sky was most beautiful, our garden was already dark.”

“Sunset no longer pleases you?” the Beast inquired, as one who will do his duty by the conversation.

“I’d never seen a sunrise—I was always asleep,” I explained. “I used to stay up very late, reading. Then we moved to the country—I suppose I like sunrise best now; I’m too tired, usually, by sunset, to appreciate it, and I’m usually in a hurry to finish something and go in to supper—or I was,” I said sadly. Longing for home broke over me suddenly and awfully, and closed my throat.

We came to a wall covered with climbing roses which I recognized at once: This must be where Father had met the Beast. We went through the break in the wall, and I looked around me at the glorious confusion; the Beast halted a few steps behind me. Then suddenly in a final fierce bloom of light before it disappeared, the sun filled the castle and its gardens with gold, like nectar in a crystal goblet; the roses gleamed like facets. We both turned towards the light, and I found myself gazing at the back of the Beast’s head. I saw that the heavy brown mane that fell to his shoulders was streaked with grey. The light went out like a snuffed candle, and we stood in soft grey twilight; the sky the sun had left behind was pink and lavender.

The Beast turned back to me. I could look at him fairly steadily this time. After a moment he said harshly: “I am very ugly, am I not?”

“You are certainly, uh, very hairy,” I said.

“You are being polite,” he said.

“Well, yes,” I conceded. “But then you called me beautiful, last night.”

He made a noise somewhere between a roar and a bark, and after an anxious minute, I decided it was probably a laugh. “You do not believe me then?” he inquired.

“Well’—no,” I said, hesitantly, wondering if this might anger him. “Any number of mirrors have told me otherwise.”

“You will find no mirrors here,” he said, “for I cannot bear them: nor any quiet water in ponds. And since I am the only one who sees you, why are you not then beautiful?”

“But—” I said, and Platonic principles rushed into my mouth so fast that they choked me silent. After a moment’s reflection I decided against a treatise on the absolute, and I said, to say something: “There’s always Greatheart. Although I’ve never noticed that he minds how I look.”

“Greatheart?”

“My horse. The big grey stallion in your stable.”

“Ah, yes,” he said, and looked at the ground.

“Is anything wrong?” I said anxiously.

“It would have been better, perhaps, if you had sent him back with your father,” said the Beast.

“Oh dear—is he not safe? Oh, tell me nothing will happen to him! Could I not send him back now? I won’t have him hurt,” I said.

The Beast shook his head. “He’s safe enough; but you see—beasts—other beasts don’t like me. You’ve noticed that nothing lives in the garden but trees and grass and flowers, and rocks and water.”

“You’ll not hurt him?” I said again.

“No; but I could, and horses know it. As I recall, your father’s horse would not come through my gates a second time.”

“That’s true,” I whispered.

“There’s no need to worry. You know now. You look after him well, and I will take care to stay away from him.”

“Perhaps—perhaps it would be better if he went home,” I said, although my heart sank at the thought of losing him. “Could you—send him?”

“I could, but not in any fashion that he would understand, and it would drive him mad. He will be all right.”

I looked up at him, wanting to believe him, and found to my surprise that I did. I smiled. “All right.”

“Come; it’s getting dark. Shall we go in? May I join you at your dinner?”

“Of course,” I said. “You are master here.”

“No, Beauty; it is you who are mistress. Ask for anything I can give you, and you shall have it.”

“My freedom” sat on my tongue, but I did not say it aloud.

“Is your room as you wish? .Is there anything you would change?”

“No—no. Everything is perfect. You are very kind.”

He brushed this away impatiently. “I don’t want your thanks. Is the bed comfortable? Did you sleep well last night?”

“Yes, of course, very well,” I said, but an involuntary gesture of my hands caught his eye.

‘

‘What have you done to your hands?’’ he demanded.

“I—oh—” I said, and realized I could not lie to him, although I did not understand why. “Last night—I tried to go out of my room. The door wouldn’t open, and—I was frightened.”

“I see,” he said; it was no more than a rumble deep in his chest. “It was on my orders that the door was locked.”

“You said I had nothing to fear,” I said.

“That is so; but I am a Beast, and I cannot always behave prettily—even for you,” he replied.

“I am sorry,” I said. “I did not understand.” There was something about the way he stood there without looking at me: Resignation born of long silent hopeless years sat heavily on him, and I found myself involuntarily anxious to comfort him. “But I am quite recovered now in my mind—and see: I am sure my hands are nearly healed too.” I pulled the bandages off as I spoke, and held my hands out for inspection. I had forgotten my ring; the diamonds and the bright ruby eyes caught a few drops of the last daylight and glittered.

“Do you like your ring?” he asked after a pause, looking at my hands.

“Yes,” I said. “Very much. And thank you for the rose seeds, too. I planted them right after Father came home, and they bloomed the day I left—so I can remember the house all covered with them,” I said wistfully.

‘Tm glad. I tried to hurry them along, of course, but it’s rather difficult to do at a distance.”

“Is it?” I said, not sure if an answer was required; and I remembered how the vines nearest the forest had grown the fastest. “And thank you for all the lovely things in Father’s saddle-bags—it was very kind of you.”

“I am not kind—you know you are thinking right now that you would much rather be without rings and roses and lace tablecloths, and be home again instead—and I don’t want your gratitude. I told you that already,” he said roughly. After a moment he continued in a different tone: “It was difficult to know what to send. Emeralds, sapphires, the usual king’s ransom and so forth, I didn’t think would be much good to you. Even gold coins might be difficult to use.”

“You chose very well,” I said.

“Did I really?” he sounded pleased. “Or are you just being polite again?”

“No, really,” I said. “I used two of the candles myself, reading. It was very extravagant of me, but it was wonderful to have good, even light to read by.”

“I sent more candles this time,” he said. “And furs, and cloth. I didn’t want to send more money.”

Blood money, I thought.

“It’s dark,” he said. “Your dinner will be waiving. Will you take my arm?”

“I’d rather not,” I said.

“Very well,” he replied.

“Let’s hurry,” I said, looking away from him. “I’m very hungry.”

The dining hall lit up at our approach. I had noticed without thinking about it that while dusk was falling as we stood in the gardens, and the pedestal lanterns were lighting elsewhere, we stood among the roses in a little pool of shadow, and the lanterns that lined our path back towards the castle remained dark.

“That’s odd,” I said. “Don’t they usually light as you approach? The candles did, last night, when I was walking through the castle.”

He made a noise like a grunt with words in it, but in no language I knew; and the lamps lit at once.

“I don’t understand,” I said.

He glanced at me. “I have long preferred the dark.”

I could think of no response; and we entered the castle. The same immense table stood, heavily laden with fine china and crystal and silver and gold, and I recognized not one cup or bowl or plate from the night before; and the air was crowded with savory smells. The Beast stood behind the great carved chair and bowed me into it; and called another chair over to him from where it stood in a row of tall chairs, no two alike, lined up against the wall. The words he used were as unfamiliar as those he had spoken to the lamps in the garden.

Then the little table with hot water and towels trotted up to me, and while I busied myself with that, serving platters jostled and rang against each other in their haste to serve my plate. A little rattling cutlery, I thought. But here even clanks and collisions are musical—I suppose because they’re made of such fine materials. What am / doing here? Grace would have looked magnificent in a throne. I feel foolish.

I glanced over at the Beast, who was sitting a little way down the table on my right. He was leaning back in his chair with one velvet knee against the table, and no place laid for him.

“Are you not joining me?” I asked in surprise.

He raised his hands—or paws, or claws. “I am a Beast,” he said. “I cannot wield knife and fork. Would you rather I left you?”

“No,” I said, and this time I didn’t need to remember to be polite. ‘

‘No; it’s nice to have company. It is lone—

some here—the silence presses around so.”

“Yes, I know,” he said, and I thought of what he had said the previous night. “Beauty,” he said, watching the parade past my plate, “you shouldn’t let them bully you that way. You can have anything you would like to eat; you need only ask for it.”

“Everything looks and smells so delicious, I couldn’t choose. I don’t mind having the decision taken out of my hands.” Around a mouthful I said: “You say I need only ask—yet the words I’ve heard you say, to the lanterns outside, and your chair here, are no language I recognize.”

“Yes; when enchantments are dragged from their world into ours they tend to be rather slow and grudging about learning the local language. But I’ve assigned two—er—well, call them handmaids, to you that should understand you.”

“The little breeze that chatters at me,” I said.

“Yes; they should seem a little more real—almost substantial to you. They’re very near our world.”

I chewed thoughtfully. “You talk as if this were all very obvious, but I don’t understand at all”

“I’m sorry,” he said. “It is rather complicated; I’ve had a long time to accustom myself to the arrangements here, but little practice in explaining them to an outsider.”

I looked again at the grey in his hair. “You are not a very—young Beast, are you?” I said.

“No,” he answered, and paused. “I have been here about two hundred years, I think.”

He did not give me time to recover from this, but went on as I stared at him, stunned, thinking, two centuries!

“Have you had any difficulty making your wants known? I will gladly assist you if necessary.”

“No-o,” I said, dragging myself back to the present, “But how would I find you if I needed you?”

“I am easily found,” he said, “if you want me.”

Shortly after that I finished my meal, and stood up. “I will wish you good night now, milord,” I said. “I find that I am already tired.”

Sitting in his chair, he was nearly as tall as my standing height. “Beauty, will you marry me?” he said.

I took a step backwards. “No,” I said.

“Do not be afraid,” he said, but he sounded unhappy. “Good night, Beauty.”

I went directly to bed and slept soundly. I heard no strange voices and felt no fear.

* * *

Several weeks passed, more quickly than I would have believed possible during those first few days. My time fell into a sort of schedule. I rose early in the morning, and after breakfast in my room went out into the gardens for a walk. I usually took Greatheart with me, on his lead rope. At home he used to follow me around like a pet dog, and sometimes when I was working in the shop for an afternoon I would let him loose to graze in the meadow that surrounded our house. He would wander over to the shop occasionally, and fill up the doorway with his shoulders while he watched Ger and me for a few minutes before returning to his meanderings. Since the Beast had warned me about other animals’ dislike of him, I had thought it wise to keep a lead on my big horse, though in fact if he had ever taken it into his head to bolt, my small strength would not have been able to do much about it. But the Beast stayed away from us, and I never saw Greatheart exhibit any uneasiness; he was placid to the point of sleepiness, and as sweet-natured as ever. Ger had been right; having him with me in exile made a big difference in my courage.

About mid-morning I returned co the castle and spent the hours till lunch reading and studying. I had forgotten more of my Greek and Latin in the nearly three years I’d been away from them than I liked to admit; and my French, which had always been weak, had been reduced to near nonexistence. One day, in a temper at my own stupidity, I was prowling through the bookshelves for something to relax me, and found a complete Faerie Queen. I had only had the opportunity to read the first two cantos before, and I seized upon these volumes with delight.

After lunch, I read again; usually Faerie Queen or Le Morte d’Arthur, after studying languages all morning, until mid-afternoon, when I changed into riding clothes and went out to take Greatheart for a gallop. Nearly every day we found ourselves traveling over unfamiliar ground, even when I thought I was deliberately choosing a route we had previously traced; even when I thought I recognized a particular group of trees or flower-strewn meadow, I could not be sure of it. I didn’t know whether this was caused by the fact that my sense of direction was worse than I’d realized, which was certainly possible, or whether the paths and fields really changed from day to day—which I thought was also possible. One afternoon we rode out farther than usual, while I was preoccupied with going over the morning’s reading in my mind. I realized with dismay that the sun was almost down when we finally turned back. I didn’t like the idea of trying to find our way after dark—or rather, I did not like the idea of being abroad on this haunted estate after the sun set—but by some sympathetic magic less than an hour’s steady jog-trot and canter brought us to the garden borders. I was sure we had been nearly three hours riding out.

But usually I had Greatheart stabled, groomed, and fed before die light faded, so that I could watch the sun set from the gardens, as I had truthfully told the Beast I liked to do. He usually met me then, in the gardens, and we walked together—I learned to trot along beside him without being too obvious about how difficult I found him to keep up with—and sometimes talked, and sometimes didn’t, and watched the sky turn colours. When it had paled to mauve or dusty gold, we went inside and he sat with me in the great dining call while I ate my dinner.

After the first few days of my enforced visit I had adopted the habit of going upstairs first, to dress for dinner. This had been one of the civilized niceties I was most pleased to dispense with after my family had left the city; but the magnificence of the Beast’s dining hall cowed me. At least I could make a few of the right gestures, even if I did look more like the scullery-maid caught trying on her mistress’s clothes than the gracious lady herself.

After dinner I went back to my room and read for a few more hours beside the fire before going to bed. And every night after dinner at the moment of parting, the

Beast said: “Will you marry me, Beauty?” And every night I said, “No,” and a iittle tremor of fear ran through me. As I came to know him better, the fear changed to pity, and then, almost, to sorrow; but I could not marry him, however much I came to dislike hurting him.

I never went outside after dark. We came in to dinner as soon as the sun sank and took its brilliant colours with it. When I had retired to my room after dinner I did not leave it again, and carefully avoided trying the door—or even going near it; nor did I look from my window into the gardens after the lanterns extinguished themselves at about midnight.

I missed my family terribly, and the pain of losing them eased very little as the weeks passed, but I learned to live with it, or around it. To my surprise, I also learned to be cautiously happy in my new life. In our life in the city my two greatest passions had been for books and horseback riding, and here I had as much as I wanted of each. I also had one other thing I valued highly, although my generally unsocial nature had never before been forced to admit it: companionship. I liked and needed solitude, for study and reflection; but I also wanted someone to talk to. It wasn’t long before I looked forward to the Beast’s daily visits, even before I had overcome my fear of him. It was difficult to completely forget fear of something as large as a bear, maned like a lion, and silent as the sun; but after a very few weeks of his company I found it was equally difficult not to like and trust him.

Even my makeshift bird feeder was successful. On the very first day I noticed that the seed had been disturbed, rearranged into little swirls and hollows that, I thought hopefully, were more likely to have been caused by birds’ feet and beaks than by errant wind; although in this castle one was never sure. But the next morning I saw a tiny winged shadow leave the sill as I approached the window; and at the end of two weeks I had half a dozen regular visitors I recognized: three sparrows, a chaffinch, a little yellow warbler, and a diminutive black-and-white creature with a striped breast that I didn’t recognize. They grew so tame that they would perch on my fingers and take grain from my hand, and chirp and whistle at me when I chirped and whistled at them. I never saw anything larger than a dove.

The weather over these enchanted lands was nearly always fine. Spring should have a good grasp on the world where my family still lived; there would be mud everywhere, and the trees would be putting out their first fragile green, and the shabby last year’s grass would be displaced by this year’s fresh growth. At the castle, the gardens remained perfect and undisturbed—by seasonal change, animal depredations, or anything else. Not only was there no sign of gardeners, visible or invisible, but there was never any sign of any need for gardeners; hedges never seemed to need trimming, nor flower beds weeding, nor trees pruning; nor did the little streams in their mosaic stone beds swell with spring floods.

The outlying lands where Greatheart and I rode were touched with the change of season; the snow patches disappeared from the ground, and new leaves appeared on the trees. But even here there was little mud; the ground thawed and grew softer under the horse’s hoofs without turning marshy, and there was little dead vegetation from past seasons, either underfoot or on the bushes and trees. The fresh young green replaced nothing brown and weary, but grew on clean polished stems and branches.

Occasionally, however, it did rain. I woke up one morning a little over a fortnight after I first arrived, and noticed how dimly the sun shone through my window. I looked out and saw a gentle grey but persistent rain falling. The garden glimmered like jewels under water, or like a mermaids’ city of which I was catching fantastic glimpses beneath the surface of a deep quiet lake. “Oh,” I said sadly. This new vision of the castle and gardens was beautiful, but it meant postponing our morning walk. I dressed and ate slowly, then wandered listlessly downstairs, thinking to walk about a little indoors, and perhaps make a conciliatory visit to Greatheart, before settling down to a long morning of study.

The Beast was standing at the front doors, which were open. He stood with his back to me as I walked down the curved marble staircase; for a moment I thought he looked like Aeolus, standing at the mouth of his thundery cavern on the mountain of the gods; a warm wind sang around him, and came up to greet me on the stairs, smelling of a green land at the end of the world. As I reached the ground floor he turned around and said gravely, “Good morning, Beauty.”

“Good morning, Beast,” I answered, wondering a little, because I had only seen him in the evenings before. I walked down the hall and came to stand beside him in the doorway. “It’s raining,” I said, but he understood the question, because he answered:

“Yes, even here it rains sometimes.” As if he thought there was need for some explanation, he went on: “I’ve found that it doesn’t do to tinker with the weather too much. The garden will take care of itself as long as I don’t try to be too clever. Snow disappears in a night, you know, and it’s never very cold here, but that’s about all. Usually it rains after nightfall,” he added apologetically.

“It does look very beautiful,” I said. I knew by this time that his kindness was real, as was his interest in my welfare. It was very mean of me to boggle at rain, and it showed how selfish and spoiled I was becoming through having my least whim granted, “All misty and mysterious. I’m sorry I was sulky; of course it has to rain, even here.”

“I thought, perhaps,” he said hesitantly, “that you might like to see a bit more of the castle this morning, since you can’t go out. I believe that there is quite a lot that you have missed.”

I nodded and smiled wryly. “I know there is. I can’t seem to keep the corridors straight in my head somehow, and as soon as I’m hopelessly lost, I turn a corner and there’s my room again. So I never learn anything. I don’t mean to complain,” I added hastily. “It’s just that I get lost so very quickly that I don’t have the chance to see very much before they—er—send me home again.”

“I quite understand,” said the Beast. “The same used to happen to me.”

Two hundred years, I thought, watching raindrops sliding slowly down the luminous pale marble.

“But I know my way around rather well by now, I think,” he continued. There was a pause. The rain seeped into the raked sand of the courtyard till it sparkled like opal. “Is there anything in particular that you would like to see?”

“No,” I said, and smiled up at him. “Anything you like.”

With a guide, the great rooms that had blurred into surfeit before my dazzled eyes during my solitary rambles became clear again, full of individual wonders. After some time we came to a portrait gallery, the first I had seen in the castle; all the paintings I had looked at thus far had avoided depicting human beings in any detail. I paused to look at these more closely. The men and women were most of them handsome, and all of them very grand. I knew little about styles and techniques of painting, but it seemed to me that they were a series, extending over a considerable period of time, possibly several centuries. I thought I saw a family resemblance, particularly among the men: tall, strong, brown-haired and brown-eyed, and a bit grim about the mouth, and they all had a certain proud tilt of eyebrow and chin and shoulder. “This looks like a family,” I said.

There were no recent portraits; the line seemed to have stopped a long time ago. “Who are they?” I said, studying the picture of a pretty woman, golden-haired and green-eyed, with a silly fluffy white lap dog, and trying to sound casual; it was the secret that hid behind the men’s eyes I really wondered about.

The Beast was silent so long I looked at him inquiringly. It was more difficult to gaze at him steadily again after looking at all the handsome, proud painted human faces. “They are the family that have owned these lands for thousands of years, since time began, and before portraits were painted,” he said at last.

He spoke in the same tone of voice that he had used in reply to all my other questions, yet for the first time in several days I was reminded of the undercurrent of thunder in his deep harsh voice, and remembered that he was a Beast. I shivered and dared ask no more.

I looked longest at the last painting in the long row: Beyond it the wall was decorated with scrolls and hangings, but there were no more portraits. This last one that held my attention was of a handsome young man, of my age perhaps; one hand held the bridle of a fine chestnut horse that was arching its neck and stamping. There was something rather terrible about this young man’s beauty, though I could not say just where the dreadfulness lay. The hand on the bridle was clenched a little too tightly; the light in the eyes was a little too bright, as if the soul itself were burning. He seemed to watch me as I looked at him, watch me with all the intensity of those eyes; the other portraits I examined had flat painted eyes that behaved as they should, vaguely refusing to focus on their audience. For a moment I was frightened; then I raised my chin and stared back. This castle was a strange place, and probably not to be trusted, but I trusted the Beast; he would not let me be bewitched by any daub.

As I stared I began unwillingly to realize just how beautiful this young man was, with his curly brown hair, high forehead, and straight nose. His chin and neck were a perfect balance between grace and strength, he was broad-shouldered and evidently tall, and the hand holding the bridle was finely shaped. He was wearing velvet of the purest sapphire hue; the white lace at his throat and wrists made his skin golden. His beauty was extraordinary, even in this good-looking family; and the passion of his expression made him loom above me like a god-ling. I looked away at last, no longer afraid, but ashamed, remembering the undersized, sallow, snub-nosed creature he looked down upon.