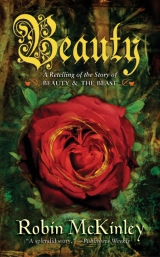

Текст книги "Beauty"

Автор книги: Robin McKinley

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 13 страниц)

His horse began to stumble over the ground, as if the footing had suddenly become much rougher. The snow covered everything. He let his mount pick its way as best it could, trying to shield his own face from the sharp-slivered wind. He did not know how long he had been traveling when he felt the wind lessen; he dropped his arm and looked around him. The snow was falling only softy now, almost caressingly, clinging to twig-tips, sliding on heaped branches. He was lost in a forest; all he could see in any direction was tall dark trees; overhead he saw nothing but their entangling branches.

In a little while they came to a track. It wasn’t much of a track, being narrow and now deep with snow, presenting itself only as a smooth ribbon of white, a slightly sunken ribbon running curiously straight between holes and hummocks and black tree trunks, straight as if it had been planned and built. A trail of any recognizable sort is a welcome thing to a man lost in a forest. He guided his tired horse to it, and it seemed to take heart, raising its head and picking its feet up a little higher as it waded through the snow.

The track widened and became what might have been a carriage-road, if there had been any reason to drive a carriage through the lonesome forests around Blue Hill. It ended, at last, before a hedge, a great, spiky, holly-grown hedge, twice as tall as a man on horseback, extending away on both sides till it was lost in the darkness beneath the trees. In the hedge, at the end of the road, was a gate, of a dull silver colour. He dismounted and knocked, and halloed, but without much hope; the heavy silence told him there was no one near. In despair, he put his hand to the latch, which fell away from his touch, and the gates swung silently open. He was uneasy, but he was also tired; and the horse was exhausted and could not go much farther. He remounted and went in.

Before him was a vast expanse of silent, unmarked snow. It was late afternoon, and the sun would soon be gone; just as he was thinking this a ray of sunlight lit up the towers standing above the trees of an orchard that stood at the centre of the vast bare field he stood in. The towers were stone, and belonged to a great grey castle, but in the light of the dying sun, they were the colour of blood, and the castle looked like a crouching animal. He rubbed his face with his hand and the fancy disappeared as quickly as the red light. A tiny breeze searched his face as if discovering who and what he was; it was gone again in a moment. Once again he took heart; he must be approaching human habitation.

The brief winter twilight escorted him as far as the orchard, and as he emerged from it on the far side, near the castle, his horse started and snorted. An ornamental garden was laid out before him, with rocks, and hedges, and grass, and white marble benches, and flowers blooming everywhere: For here no snow had fallen. He was so weary he almost laughed, thinking this was some trick of fatigue, a waking dream. But the air that touched his face was warm; he threw his hood back and loosened his cloak; he breathed deeply, and found the smell of the flowers heavy and delightful. There was no sound but of the tiny brooks running through the gardens. There were lanterns everywhere, standing on black or silver carved posts, or hanging from the limbs of the small shaped trees; they cast a warm golden light of few shadows. His horse walked forwards as he stared around him, bewildered; and when they stopped again he saw they had come to one corner of a wing of the castle. There was an open door before them, and more lanterns lit the inside of what was obviously a stable.

He hesitated a moment, then called aloud, but got no answer; by now he was expecting none. He dismounted slowly and stared around a minute longer; then he straightened his shoulders and led his horse inside, as if empty enchanted castles were a commonplace. When the first stall he came to slid its doors open at his approach, he only swallowed hard once or twice, and took the horse in. Inside there was fresh litter, and hay in a hanging net; and water that ran into a marble basin from a marble trough, and ran sweetly out through a marble drain; a steaming mash was in the manger. He said “Thank you” to the air in general, and felt suddenly that the silence was a listening one. He pulled the saddle and bridle off the horse, and outside the stall found racks to hang the harness on, which he was sure had not been there when they entered. Except for himself and his horse, the long stable was empty, although there was room enough for hundreds of horses.

The sweet smell of the hot mash reminded him suddenly how hungry he was. He left the stable and shut the door behind him. He looked around, and across the courtyard formed by two wings of the castle, one of which was the stable he had just left, another door opened as if it had been waiting only to catch his eye. He went towards it, giving a look as he passed it to what he supposed was the main entrance: double arched doors twenty feet high and another twenty broad, bound with iron and decorated with gold. Around the rim of the doors was another arch, six feet wide, of the same dull silver metal that the front gates were made of, here worked into marvelous relief shapes that seemed to tell a story; but he did not pause to look more closely. The door that beckoned to him was of a more reasonable size. He went in with scarcely a hesitation. A large room lay before him, lit by dozens of candles in candelabra, and hundreds more candles were set in a great chandelier suspended from the ceiling. On one wall was a fireplace big enough to roast a bear; there was a fire burning in it. He warmed himself at it gratefully, for in spite of the flower garden the enchanted castle was cool, and he was chilled and wet after his long ride.

There was a table set for one, drawn snugly near the fire. As he turned to look at it, the chair, padded with red velvet, moved away from the table a few inches, swinging towards him; and the covers slid off the dishes, and hot water descended from nowhere into a china teapot. He hesitated. He had seen no sign of his host—nor, indeed of any living thing that goes on legs, or wings: There weren’t even any birds in the garden—and surely hidden somewhere in this vast pile was the someone who was waited on so efficiently. And one never knew about enchantments; perhaps he, whoever he was, lived alone, and these invisible servants were mistaking this stranger

X

for their master, who would be very angry when he discovered what had happened. Or perhaps there was something wrong with the food, and he would turn into a frog, or fall asleep for a hundred years.... The chair jiggled a little, impatiently, and the teapot rose up and poured a stream of the sweetest-smelling tea he had ever known into a cup of translucent china. He was very hungry; he sighed once, then sat down and ate heartily.

When he was done, a couch he hadn’t noticed before had been made up into a bed. He undressed and lay down, and fell immediately into a dreamless sleep.

No more than the usual eight hours seemed to have passed when he awoke. The day was new; the sun had not yet risen above the tops of the tall, white-crowned forest trees, and a grey but gentle light slipped through the tall leaded windows and splashed on the floor. His clothes had been cleaned, and were folded neatly over the back of the red velvet chair; and for his coarse shirt, a fine linen one had been substituted. His boots and breeches looked new, and his cloak was mysteriously healed of its travel tears and stains. There were tea and toast and an elegantly poached egg on the little table, and a rust-coloured chrysanthemum floating in a crystal bowl.

There was still no sign of his host, and he grew anxious. He wanted to be on his way, but he did not wish to leave without expressing his gratitude to someone—and furthermore he still had no idea where he was, and would have liked to ask directions. He went outside, and then into the stable, where he found his horse relaxed and comfortable, pulling at wisps of hay. The tack outside the stall had been cleaned and mended, and the bits and buckles were polished till they sparkled. He went outside again, and looked around; went round the corner of the castle and stared across more gardens, and grassy fields beyond. The snow had disappeared entirely, and the green was the green of early summer. Far across the fields he saw the black border of the wood, and as he strained his eyes something shiny winked at him, something that might be another gate. “Very well,” he said aloud. “I will go that way.”

He went back into the stable, and saddled the horse, who looked at him reproachfully. He took a last look around the courtyard before riding out, and in a moment of whimsy stood up in his stirrups and bowed to the great front doors. “Thank you very much,” he said. “After a night’s rest here—at least I’m assuming it was only a night—I feel better than I have in years. Thank you.” There was no answer.

He jogged slowly through the gardens. The horse was as fresh and frisky as a youngster, and suited his own light-hearted mood. The thought of the forest held no terror for him; he was certain he would easily find a way out of it; and perhaps tonight he would be with his family again. He was distracted from his pleasant musings by a walled garden opening off the path to his right; the wall was waist-high, and covered with the largest and most beautiful climbing roses that he had ever seen. The garden was full of them; inside the rose-covered wall were rows of bushes: white roses, red roses, yellow, pink, flame-colour, maroon; and a red so dark it was almost black.

This arbour of roses seemed somehow different from

X

the great gardens that lay all around the castle, but different in some fashion he could not define. The castle and its gardens were everywhere silent and beautifully kept; but there was a self-containment, even almost a self-awareness here, that was reflected in the petals of each and every rose, and drew his eyes from the path.

He dismounted, and walked in through a gap in the wall, the reins in his hand; the smell of these flowers was wilder and sweeter than that of poppies. The ground was carpeted with petals, and yet none of the flowers were dead or dying; they ranged from buds to the fullest bloom, but all were fresh and lovely. The petals he and the horse trampled underfoot took no bruise.

“I hadn’t managed to get you any rose seeds in the city, Beauty,” Father continued. “I bought peonies, marigolds, tulips; but the only roses to be had were cuttings or bushes. I even thought of bringing a bush in a saddlebag, like a kidnapped baby.”

“It doesn’t matter, Father,” I said.

His failure to find rose seeds for his youngest daughter was recalled to his mind as he gazed at the gorgeous riot before him, and he thought: I must be within a day’s journey of home. Surely I could pick a bud—just one flower—and if I carried it very carefully, it would survive a few hours’ journey. These are so beautiful: They’re finer than any we had in our city garden—finer than any I’ve ever seen. So he stooped and plucked a bud of a rich red hue.

There was a roar like that of a wild animal, for certainly nothing human could make a noise like that; and the horse reared and plunged in panic.

“Who are you, that you steal my roses, that I value above all things? Is it not enough that I have fed and sheltered you, that you reward me with injustice? But your crime shall not go unpunished.”

The horse stood still, swearing with fear, and he turned to face the owner of the deep harsh voice: He was confronted by a dreadful Beast who stood beyond the far wall of the rose garden.

Father replied in a shaking voice: “Indeed, sir, I am deeply grateful for your hospitality, and I humbly beg your pardon. Your courtesy has been so great that I never imagined that you would be offended by my taking so small a souvenir as a rose.”

“Fine words,” roared die Beast, and strode over the wall as if it were not there. He walked like a man, and was dressed like one, which made him the more horrible, as did an articulate voice proceeding from such a countenance. He wore blue velvet, with lace at the wrists and throat; his boots were black. The horse strained at its bridle but did not quite bolt. “But your flattery will not save you from the death you deserve.”

“Alas,” said Father, and fell to his knees. “Let me beg for mercy; indeed, much misfortune has come to me already.”

“Your misfortunes seem to have robbed you of your sense of honour, as you would rob me of my roses,” rumbled the Beast, but he seemed disposed to listen; and Father, in his despair, told him of the troubles he had had. He finished: “It seemed such a cruel blow not even to be able to take my daughter Beauty the little packet of rose seeds she had asked for; and when I saw your magnificent garden, I thought that I might at least take her a rose from it. I humbly beg your forgiveness, noble sir, for you must see that I meant no harm.”

The Beast thought for a moment and then said: “I will spare your miserable life on one condition: that you will give me one of your daughters.”

“Ah!” cried Father. “I cannot do that. You may think me lacking in honour, but I am not such a cruel father that I would buy my own life with the life of one of my daughters.”

The Beast chuckled grimly. “Almost I think better of you, merchant. Since you declare yourself so bravely I will tell you this for your comfort: Your daughter would take no harm from me, nor from anything that lives in my lands,” and he threw out an arm that swept in all the wide fields and the castle at their centre. “But if she comes, she must come here of her own free will, because she loves you enough to want to save your life—and is courageous enough to accept the price of being separated from you, and from everything she knows. On no other condition will I have her.”

He paused; there was no sound but the horse’s panting breath. Father stared at the Beast, not able to look away; and the Beast turned from his contemplation of the green meadow, and looked back at him. “I give you a month. At the end of that time you must come back here, with or without your daughter. You will find my castle easily: You need only get lost in the woods around it—and it will find you. And do not imagine that you can hide from your doom, for if you do not return in a month, I will come and fetch you!”

Father could think of nothing else to say; he had a month in which to say good-bye to everything that was dear to him. He mounted with difficulty, for with the Beast standing so near, the horse was nervous and would not stand still.

As he gathered up the reins, the Beast was suddenly beside him. “Take the rose to Beauty, and farewell for a rime. Your way lies there,” and he pointed towards the winking silver gate. Father had forgotten all about the rose; he took it in his hand, shrinking, from the Beast; and as he took it the Beast said, “Don’t forget your promise!” and he slapped Father’s mount on die rump. The horse leaped forwards with a scream of terror, and they galloped across the fields as if running for their lives. The gates swung open as they approached, and they plunged through and into die forest, floundering in the snow until he could pull the poor animal back to a more collected pace.

“I don’t remember die rest of that journey very well,” said Father. “It started to snow again. I held die reins in one hand, and the red rose in die other. I don’t remember stopping until the poor horse stumbled out of the edge of die trees and I recognized our house in the clearing.”

Father stopped speaking, and as though he could not look at us, returned his gaze to the fire. The shadows from die restless flames twisted around the scarlet rose, and it seemed to nod its heavy head at the truth of Father’s tale. We all sat stunned, not comprehending anything but die fact that disaster had struck us—again; it was like the first shock of business ruin in the city. It had been impossible to imagine just what losing our money, our home, might mean; but it was numbing, dreadful. This was worse, and we had yet only begun to feel it, because it was Father’s life.

I have no idea how long the silence lasted. I was staring at the rose, silent and serene on the mantelpiece, and I heard my own voice say, “When the month is up, Father, I will return with you.”

“Oh, no,” from Hope. “No one will go,” said Grace. Ger frowned down at his hands. Father remained staring at the fire, and after a tiny pause, he said: “I’m afraid someone must go, Grace. But I am going alone.”

“You are not,” I said.

“Beauty—” Hope wailed.

“Father,” I said, “he won’t harm me. He said so.”

“We can’t spare you, child,” said Father.

“Mmph,” I said. “We can’t spare you.”

He lifted his shoulders, “You would soon have to spare me anyway. You are young, child. I thank you for your offer, but I will go alone.”

“I am nor offering,” I said. “I am going.”

“Beauty!” Grace said sharply. “Stop it. Father, why must anyone go? He will not truly come to take you away. You are safe here. Surely you are safe once you are away from his gates.”

“Yes, of course,” said Hope. “Ger, tell them. Perhaps they’ll listen to you.”

Ger sighed. “I’m sorry, Hope my dearest, but I agree with your father and with Beauty. There is no escaping this doom.”

Hope sucked in her breath with a gasp, then broke out crying. She buried her face in Ger’s shoulder and he stroked her bright hair with his hand.

“If it weren’t for the rose, I might not believe it.... I blame myself for this; I should have warned you better,” Ger said very low. “There have been stories about the evil in that wood for generations; I should not have ignored them.”

“You didn’t,” I said. “You told us to stay out of it, that it was old and dangerous, and there were—funny stories about it,”

“There was nothing you could have done, lad,” said Father. “Don’t worry yourself about it. It was my own fault for taking a foolish risk in bad weather. My own fault, none other’s; and none other shall pay for it.”

Grace said: “Funny stories, Hope and I heard stories about a monster who lived in the forest, a creature that lived in the forest and ate everything that walked or flew, which is why there is no game in it. And how it likes to lure travelers to their deaths . , . and it’s very, very old, as old as the hills, as old as the trees in its forest. We never mentioned it to the rest of you because we thought you’d laugh; Molly told us about it. To warn us to stay out of the wood.” I looked over at Ger. The stories he’d told me two years ago had never been mentioned again.

Hope had stopped crying. “Yes, we thought it was all foolishness; and we needed no urging to stay out of that awful wood,” she said. The tears began to run down her cheeks again; but she sat up and leaned against Ger, who put his arm around her. “Oh, Father, surely you can stay here.”

Father shook his head; and Ger said abruptly: “What’s in your saddle-bags?”

“Nothing very grand. A little money, though; I thought we might buy a cow, instead of having to bring milk from town for the babies, and—well, there’s probably not enough.”

Ger stood up, still holding Hope’s hand, then knelt by the leather bags, still piled in their corner. Grace and Hope, usually the most conscientious of housekeepers, had for some reason let them lie untouched. “I noticed when Beauty and I brought them in yesterday that they were very heavy.”

“They were? They aren’t—I mean, they can’t be. I didn’t have all that much.” Father knelt beside Ger and unbuckled the top of one and threw back the flap. Dazed, he lifted out two dozen fine wax candles, a linen tablecloth with a delicate lace edge, several bottles of very old wine and a bottle of even older brandy, and a silver corkscrew with the head of a griffin, with red jewels for eyes that looked very much like rubies; and wrapped in a soft leather pouch was a carving knife with an ivory handle cut in the shape of a leaping deer, with its horns laid along its straining back. At the bottom of the bag, piled wrist deep, were coins: gold, silver, copper, brass. Buried among the coins were three small wooden boxes, and inlaid on each of their polished lids was an initial in mother-of-pearl: G, H, and B. “Grace, Hope, and Beauty,” said Father, and handed them to us. In my sisters’ boxes were golden necklaces, and ropes of pearls, diamonds, emeralds; topaz and garnet earrings; sapphires in bracelets, opals in rings. They made a shining incongruous pile in laps of homespun.

My box was filled to the brim with little brownish, greenish, irregularly shaped roundish things. I picked up a handful, and let them run through my fingers, and as they pattered into the box again I laughed suddenly, as I guessed what they must be: “Rose seeds!” I said. “This Beast has a sense of humour, at least. We shall get along quite well together, perhaps.”

“Beauty,” Father said. “I refuse to let you go.”

“What will you do then, tie me up?” I said. “I wilt go, and what’s more, if you don’t promise right now to take me with you when the rime comes, I will run off tonight while you’re asleep. I need only get lost in the woods, you said, to find the castle.”

“I can’t bear this,” said Hope. “There must be a way out.”

“No; there is no way out,” said Father.

“And you agree?” asked Grace. Ger nodded. “Then I must believe it,” she said slowly. “And one of us must go. But it need not be you, Beauty; I could go,”

“No,” I said, “The rose was for me. And I’m the youngest—and the ugliest. The world isn’t losing much in me. Besides, Hope couldn’t get along without you, nor could the babies, while my best skills are cutting wood and tending the garden. You can get any lad in the village to do that.”

Grace looked at me a long minute. “You know I always wear you down in the end,” I said.

“I see you are very determined,” she said. “I don’t understand why.”

I shrugged. “Well, I’m turned eighteen. I’m ready for an adventure.”

“I can’t—” began Father.

“I’d let her have her way, if I were you,” said Ger.

“Do you realize what you’re saying?” shouted Father, standing up abruptly and spilling the empty leather satchel off his lap. “I have seen this Beast, this monster, this horror, and you have not. And you are willing that I should give him—//—my youngest daughter, your sister, to spare my own wretched life!”

“You are the one who does not understand, Papa,” I said. “We are not asking that I be killed in your stead, but that I be allowed to save your life. It is an honourable Beast at least; I am not afraid.” Father stared at me, as if he saw the Beast reflected in my eyes. I said: “He cannot be so bad if he loves roses so much.”

“But he is a Beast,” said Father helplessly.

I saw that he was weakening, and wishing only to comfort him I said, “Cannot a Beast be tamed?”

As Grace had a few minutes before, Father stared down at me as I sac curled up on the floor with the little wooden box in my Jap. “I always get my own way in the end, Papa,” I said.

“Yes, child, I know; and now I regret it,” he said heavily. “You ask the impossible, and yet—this is an impossible thing. Very well. When the month is up, we will go together.”

“You won’t see your roses bloom,” murmured Hope.

“I’ll plant them tomorrow. They’re enchanted too—if I’m lucky, maybe I will see them,” I said.

2

That night I couldn’t sleep. Father had gone upstairs immediately after he agreed to let me go to the castle with him in a month’s time; he had said no further word, and I followed him up the stairs only a few minutes later, fearing questions, and sensing an ominous quiver in the silence.

I sat on my bed and looked out at the quiet woods, black and silver in snow and moonlight, and serene. There was nothing watchful or brooding about that stillness; whatever secrets were hidden in that forest were so perfectly kept that their existence could not be suspected nor even imagined by any rational faculty.

So

I had been granted my wish; I would go and claim the Beast’s promise to take the daughter in the father’s place. Grace’s question came back to me, and the beaten look on Father’s face: Why was I so determined? “I wish I knew,” I said aloud. I believed that my decision was correct, that I and no other should fulfill the obligation; but a sense of responsibility, if that was what it was, did not explain the intensity of my determination.

I had brought the little wooden box with my initial on it upstairs with me. I poured its contents onto my bed; the tiny dark drops gleamed dully in the moonlight as they clattered one over another. The last thing to fall out of the box was bigger, an icy yellow under the pale light, and it bounced and rang as it landed, spraying seeds across the bed. I picked it up. It was a ring, shaped like a griffin, like the silver handle of the corkscrew downstairs. But this griffin was gold, and it had its mouth open, with diamond fangs glittering cold, and its wings spread: The wings were the band that fitted around the finger; they overlapped at the back, next to the palm of the hand. The creature was rearing up, claws stretched out. It looked fine and noble, with its neck arched and its head thrown back, the line of its body making a taut and graceful curve. It did not look evil, nor predatory; it was proud, not vicious. I put it on my finger, which it fitted perfectly, and hastily scooped the seeds back into the brown box. I would have only a few hours of sleep now, and I could ill afford to waste a day by being tired—especially after tonight, I thought, my hand pausing as I closed the lid. Especially during my last four weeks. Three weeks and five days.

I dreamed of the castle that Father had told us about. I seemed to walk quickly down long halls with high ceilings. I was looking for something, anxious that I could not find it. I seemed to know the castle very well; I did not hesitate as I turned corners, went up stairs, down stairs, opened doors; nor did I linger to look at the wonderful rooms, the frescoed ceilings, the paintings on the walls, the carved furniture. My sleeping self was dazzled, bewildered; but the dream self went on, more and more anxious, till I awoke shivering with the first light of dawn fingering my face. I dressed hurriedly, hesitated, looking at my hand, then pulled the ring off and hid it under my pillow; a needless gesture since no one but myself ever entered my little attic room. I finished lacing my boots as I went downstairs—two activities that did not mix well, and I had to do my boots all over again when I sat down at the kitchen table.

The same uneasy silence that had characterized Father’s first day home continued; but with a difference. Yesterday we had feared a doom we did nor know; today the doom was known by us all, and feared no less. No one spoke at breakfast except the babies, and I left the table first.

I frowned at the ground outside. Most of the snow from the blizzard Father had been lost in had melted quickly under yesterday’s warm sun, and from the warm touch of the morning wind on my cheek I thought that what remained would soon disappear; but the ground was still much too hard to be planting anything. Nor, if I managed to chop a few holes, would the seeds be likely to find the cold earth very hospitable. They’re magical, after all, I thought. I’ll do what I can.

I borrowed a pick from Ger, and fetched a spade from my gardening tools, and set to work cutting a narrow, shallow trench around the house, close to the outside wall where perhaps the ground was a little warmer than in the meadow or the garden. By lunchtime I was tired and sweating, but I had sprinkled my seeds in the trench and covered them over roughly; and had a few left to bury along one wall of the stable and one wall of the shop. No one said anything to me, although I should have been tending the animals and chopping wood.

At the noon meal Grace said, “I can’t just ignore what we decided—or what Beauty decided for us—last night, as we all seem to be trying to do. Beauty, child, I won’t try to dissuade you—” She hesitated. “But is there any-thing we can do? Anything you’d like, perhaps, to take with you?” The tone of her voice said that she felt she was offering me silk thread to build a bridge across a ravine.

“It will be so lonesome,” said Hope, timidly. “Not even any birds in the trees.” The canary was singing his early-afternoon-on-the-threshold-of-spring song.

There was a pause while I stared at my soup and thought: There isn’t anything I want to take. The clothes I stand up in, and one change—about all I’ve got anyway. They can keep the dress I wore to Hope’s wedding, and cut it up and use it for baby clothes. The skirt I wear to church will fit either of my sisters with just a little alteration. If the Beast wants me to look fine, he’ll have to produce his own tailor. I thought of Father’s description of velvet and lace; and it occurred to me that in my dream

I had been richly dressed in rustling embroidered skirts and soft shoes. I could almost feel those shoes on my feet, instead of my scratched and dirty boots. I was still staring at my soup, but I saw only beans and onions and carrots; I rearranged the pattern with my spoon.

Ger said: “Greatheart will be a little company for her, at least.”

I looked up. “I had hoped to ride him there, but I’ll send him back with Father. You need him here.”

“Nay, girl,” said Ger in an inflection not his own, “he’ll not eat if you go off and leave him, He goes with you.”

I put down my spoon. “Stop it, Ger, don’t tease me. I can’t take him. You need him here.”

“We’ll get along without,” Ger said in his own voice. “We have an extra horse now, don’t forget, and we can buy another if we need it—with the money your father brought back from the city. They won’t be Greatheart’s equal, but they’ll do us.”