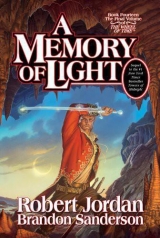

Текст книги "A Memory of Light"

Автор книги: Robert Jordan

Соавторы: Brandon Sanderson

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 71 страниц)

A Memory of Light

Robert Jordan & Brandon Sanderson

For Harriet,

the light of Mr. Jordan's life,

and for Emily,

the light of mine.

And the Shadow fell upon the Land, and the World was riven stone from stone. The oceans fled, and the mountains were swallowed up, and the nations were scattered to the eight corners of the World. The moon was as blood, and the sun was as ashes. The seas boiled, and the living envied the dead. All was shattered, and all but memory lost, and one memory above all others, of him who brought the Shadow and the Breaking of the World. And him they named Dragon.

—from Aleth nin Taerin alt a Camora,The Breaking of the World.Author unknown, the Fourth Age.

PROLOGUE

By Grace and Banners Fallen

Bayrd pressed the coin between his thumb and forefinger. It was thoroughly unnerving to feel the metal squish.

He removed his thumb. The hard copper now clearly bore its print, reflecting the uncertain torchlight. He felt chilled, as if he’d spent an entire night in a cellar.

His stomach growled. Again.

The north wind picked up, making torches sputter. Bayrd sat with his back to a large rock near the center of the war camp. Hungry men muttered as they warmed their hands around firepits; the rations had spoiled long ago. Other soldiers nearby began laying all of their metal—swords, armor clasps, mail—on the ground, like linen to be dried. Perhaps they hoped that when the sun rose, it would change the material back to normal.

Bayrd rolled the once-coin into a ball between his fingers. Light preserve us, he thought. Light . . . He dropped the ball to the grass, then reached over and picked up the stones he’d been working with.

“I want to know what happened here, Karam,” Lord Jarid snapped. Jarid and his advisors stood nearby in front of a table draped with maps. “I want to know how they drew so close, and I want that bloody Darkfriend Aes Sedai queen’s head!” Jarid pounded his fist down on the table. Once, his eyes hadn’t displayed such a crazed fervor. The pressure of it all—the lost rations, the strange things in the nights—was changing him.

Behind Jarid, the command tent lay in a heap. Jarid’s hair—grown long during their exile—blew free, face bathed in ragged torchlight. Bits of dead grass still clung to his coat from when he’d crawled out of the tent.

Baffled servants picked at the iron tent spikes, which—like all metal in the camp—had become soft to the touch. The tent’s mounting rings had stretched and snapped like warm wax.

The night smelled wrong. Of staleness, of rooms that hadn’t been entered in years. The air of a forest clearing should not smell like ancient dust. Bayrd’s stomach growled again. Light, but he would’ve liked to have something to eat. He set his attention on his work, slapping one of his stones down against the other.

He held the stones as his old pappil had taught him as a boy. The feeling of stone striking stone helped push away the hunger and coldness. At least something was still solid in this world.

Lord Jarid glanced at him, scowling. Bayrd was one of ten men Jarid had insisted guard him this night. “I will have Elayne’s head, Karam,” Jarid said, turning back to his captains. “This unnatural night is the work of her witches.”

“Her head?” Eri’s skeptical voice came from the side. “And how, precisely, is someone going to bring you her head?”

Lord Jarid turned, as did the others around the torchlit table. Eri stared at the sky; on his shoulder, he wore the mark of the golden boar charging before a red spear. It was the mark of Lord Jarid’s personal guard, but Eri’s voice bore little respect. “What’s he going to use to cut that head free, Jarid? His teeth?”

The camp stilled at the horribly insubordinate line. Bayrd stopped his stones, hesitating. Yes, there had been talk about how unhinged Lord Jarid had become. But this?

Jarid sputtered, face growing red with rage. “You dare use such a tone with me? One of my own guards?”

Eri continued inspecting the cloud-filled sky.

“You’re docked two months’ pay,” Jarid snapped, but his voice trembled. “Stripped of rank and put on latrine duty until further notice. If you speak back to me again, I’ll cut out your tongue.”

Bayrd shivered in the cold wind. Eri was the best they had in what was left of their rebel army. The other guards shuffled, looking down.

Eri looked toward the lord and smiled. He didn’t say a word, but somehow, he didn’t have to. Cut out his tongue? Every scrap of metal in the camp had gone soft as lard. Jarid’s own knife lay on the table, twisted and warped—it had stretched thin as he pulled it from his sheath. Jarid’s coat flapped, open; it had had silver buttons.

“Jarid . . .” Karam said. A young lord of a minor house loyal to Sarand, he had a lean face and large lips. “Do you really think . . . really think this was the work of Aes Sedai? All of the metal in the camp?”

“Of course,” Jarid barked. “What else would it be? Don’t tell me you believe those campfire tales. The Last Battle? Phaw.” He looked back at the table. Unrolled there, with pebbles weighting the corners, was a map of Andor.

Bayrd turned back to his stones. Snap, snap, snap. Slate and granite. It had taken work to find suitable sections of each, but Pappil had taught Bayrd to recognize all kinds of stone. The old man had felt betrayed when Bayrd’s father had gone off and become a butcher in the city, instead of keeping to the family trade.

Soft, smooth slate. Bumpy, ridged granite. Yes, some things in the world were still solid. Some few things. These days, you couldn’t rely on much. Once immovable lords were now soft as . . . well, soft as metal. The sky churned with blackness, and brave men—men Bayrd had long looked up to—trembled and whimpered in the night.

“I’m worried, Jarid,” Davies said. An older man, Lord Davies was as close as anyone was to being Jarid’s confidant. “We haven’t seen anyone in days. Not farmer, not queen’s soldier. Something is happening. Something wrong.”

“She cleared the people out,” Jarid snarled. “She’s preparing to pounce.”

“I think she’s ignoring us, Jarid,” Karam said, looking at the sky. Clouds still churned there. It seemed like months since Bayrd had seen a clear sky. “Why would she bother? Our men are starving. The food continues to spoil. The signs—”

“She’s trying to squeeze us,” Jarid said, eyes wide with fervor. “This is the work of the Aes Sedai.”

Stillness came suddenly to the camp. Silence, save for Bayrd’s stones. He’d never felt right as a butcher, but he’d found a home in his lord’s guard. Cutting up cows or cutting up men, the two were strikingly similar. It bothered him how easily he’d shifted from one to the other.

Snap, snap, snap.

Eri turned. Jarid eyed the guard suspiciously, as if ready to scream out harsher punishment.

He wasn't always this bad, was he? Bayrd thought. He wanted the throne for his wife, but what lord wouldn’t? It was hard to look past the name. Bayrd’s family had followed the Sarand family with reverence for generations.

Eri strode away from the command post.

“Where do you think you’re going?” Jarid howled.

Eri reached to his shoulder and ripped free the badge of the Sarand house guard. He tossed it aside and left the torchlight, heading into the night toward the winds from the north.

Most men in the camp hadn’t gone to sleep. They sat around firepits, wanting to be near warmth and light. A few with clay pots tried boiling cuts of grass, leaves, or strips of leather as something, anything, to eat.

They stood up to watch Eri go.

“Deserter,” Jarid spat. “After all we’ve been through, now he leaves. Just because things are difficult.”

“The men are starving, Jarid,” Davies repeated.

“I’m aware. Thank you so much for telling me about the problems with every bloody breath you have” Jarid wiped his brow with his trembling palm, then slammed it on his map. “We’ll have to strike one of the cities; there’s no running from her, not now that she knows where we are. Whitebridge. We’ll take it and resupply. Her Aes Sedai must be weakened after the stunt they pulled tonight, otherwise she’d have attacked.”

Bayrd squinted into the darkness. Other men were standing, lifting quarterstaffs or cudgels. Some went without weapons. They gathered sleeping rolls, hoisted packs of clothing to their shoulders. Then they began to trail out of the camp, their passage silent, like the movement of ghosts. No rattling of chain mail or buckles on armor. The metal was all gone. As if the soul had been stripped from it.

“Elayne doesn’t dare move against us in strength,” Jarid said, perhaps convincing himself. “There must be strife in Caemlyn. All of those mercenaries you reported, Shiv. Riots, maybe. Elenia will be working against Elayne, of course. Whitebridge. Yes, Whitebridge will be perfect.

“We hold it, you see, and cut the nation in half. We recruit there, press the men in western Andor to our banner. Go to . . . what’s the place called? The Two Rivers. We should find able hands there.” Jarid sniffed. “I hear they haven’t seen a lord for decades. Give me four months, and I’ll have an army to be reckoned with. Enough that she won’t dare strike at us with her witches . . .”

Bayrd held his stone up to the torchlight. The trick to creating a good spearhead was to start outward and work your way in. He’d drawn the proper shape with chalk on the slate, then had worked toward the center to finish the shape. From there, you turned from hitting to tapping, shaving off smaller bits.

He’d finished one side earlier; this second half was almost done. He could almost hear his pappil whispering to him. We’re of the stone, Bayrd. No matter what your father says. Deep down, we’re of the stone.

More soldiers left the camp. Strange, how few of them spoke. Jarid finally noticed. He stood up straight and grabbed one of the torches, holding it high. “What are they doing? Hunting? WeVe seen no game in weeks. Setting snares, perhaps?”

Nobody replied.

“Maybe they’ve seen something,” Jarid muttered. “Or maybe they think they have. I’ll stand no more talk of spirits or other foolery; the witches are creating apparitions to unnerve us. That’s . . . that’s what it has to be.”

Rustling came from nearby. Karam was digging in his fallen tent. He came up with a small bundle.

“Karam?” Jarid said.

Karam glanced at Lord Jarid, then lowered his eyes and began to tie a coin pouch at his waist. He stopped and laughed, then emptied it. The gold coins inside had melted into a single lump, like pigs’ ears in a jar. Karam pocketed this lump. He fished in the pouch and brought out a ring. The blood-red gemstone at the center was still good. “Probably won’t be enough to buy an apple, these days,” he muttered.

“I demand to know what you are doing,” Jarid snarled. “Is this your doing?” He waved toward the departing soldiers. “You’re staging a mutiny, is that it?”

“This isn’t my doing,” Karam said, looking ashamed. “And it’s not really yours, either. I’m . . . I’m sorry.”

Karam walked away from the torchlight. Bayrd found himself surprised. Lord Karam and Lord Jarid had been friends from childhood.

Lord Davies went next, running after Karam. Was he going to try to hold the younger man back? No, he fell into step beside Karam. They vanished into the darkness.

“I’ll have you hunted down for this!” Jarid yelled after them, voice shrill. Frantic. “I will be consort to the Queen! No man will give you, or any member of your Houses, shelter or succor for ten generations!”

Bayrd looked back at the stone in his hand. Only one step left, the smoothing. A good spearhead needed some smoothing to be dangerous. He brought out another piece of granite he’d picked up for the purpose and carefully began scraping it along the side of the slate.

Seems I remember this better than I'd expected, he thought as Lord Jarid continued to rant.

There was something powerful about crafting the spearhead. The simple act seemed to push back the gloom. There had been a shadow on Bayrd, and the rest of the camp, lately. As if . . . as if he couldn’t stand in the light no matter how he tried. He woke each morning feeling as if someone he’d loved had died the day before.

It could crush you, that despair. But the act of creating something—anything—fought back. That was one way to challenge . . . him. The one none of them spoke of. The one that they all knew was behind it, no matter what Lord Jarid said.

Bayrd stood up. He’d want to do more smoothing later, but the spearhead actually looked good. He raised his wooden spear haft—the metal blade had fallen free when evil had struck the camp—and lashed the new spearhead in place, just as his pappil had taught him all those years ago.

The other guards were looking at him. “We’ll need more of those,” Morear said. “If you’re willing.”

Bayrd nodded. “On our way out, we can stop by the hillside where I found the slate.”

Jarid finally stopped yelling, his eyes wide in the torchlight. “No. You are my personal guard. You will not defy me!”

Jarid jumped for Bayrd, murder in his eyes, but Morear and Rosse caught the lord from behind. Rosse looked aghast at his own mutinous act. He didn’t let go, though.

Bayrd fished a few things out from beside his bedroll. After that, he nodded to the others, and they joined him—eight men of Lord Jarid’s personal guard, dragging the sputtering lord himself through the remnants of camp. They passed smoldering fires and fallen tents, abandoned by men who were trailing out into the darkness in greater numbers now, heading north. Into the wind.

At the edge of camp, Bayrd selected a nice, stout tree. He waved to the others, and they took the rope he’d fetched and tied Lord Jarid to the tree. The man sputtered until Morear gagged him with a handkerchief.

Bayrd stepped in close. He tucked a waterskin into the crook of Jarid's arm. “Don’t struggle too much or you’ll drop that, my Lord. You should be able to push the gag off—it doesn’t look too tight—and angle the waterskin up to drink. Here, I’ll take out the cork.”

Jarid stared thunder at Bayrd.

“It’s not about you, my Lord,” Bayrd said. “You always treated my family well. But, here, we can’t have you following along and making life difficult. There’s just something that we need to do, and you’re stopping everyone from doing it. Maybe someone should have said something earlier. Well, that’s done. Sometimes, you let the meat hang too long, and the entire haunch has to go.”

He nodded to the others, who ran off to gather bedrolls. He pointed Rosse toward the slate outcropping nearby and told him what to look for in good spearhead stone.

Bayrd turned back to the struggling Lord Jarid. “This isn’t witches, my Lord. This isn’t Elayne . . . I suppose I should call her the Queen. Funny, thinking of a pretty young thing like that as queen. I’d rather have bounced her on my knee at an inn than bow to her, but Andor will need a ruler to follow to the Last Battle, and it isn’t your wife. I’m sorry.”

Jarid sagged in his bonds, the anger seeming to bleed from him. He was weeping now. Odd thing to see, that.

“I’ll tell people we pass—if we pass any—where you are,” Bayrd promised, “and that you probably have some jewels on you. They might come for you. They might.” He hesitated. “You shouldn’t have stood in the way. Everyone seems to know what is coming but you. The Dragon is reborn, old bonds are broken, old oaths done away with . . . and I’ll be hanged before I let Andor march to the Last Battle without me.”

Bayrd left, walking into the night, raising his new spear onto his shoulder. I have an oath older than the one to your family, anyway. An oath the Dragon himself couldn’t undo. It was an oath to the land. The stones were in his blood, and his blood in the stones of this Andor.

Bayrd gathered the others and they left for the north. Behind them in the night, their lord whimpered, alone, as the ghosts began to move through camp.

Talmanes tugged on Selfar’s reins, making the horse dance and shake his head. The roan seemed eager. Perhaps Selfar sensed his master’s anxious mood.

The night air was thick with smoke. Smoke and screams. Talmanes marched the Band alongside a road clogged with refugees smudged with soot. They moved like flotsam in a muddy river.

The men of the Band eyed the refugees with worry. “Steady!” Talmanes shouted to them. “We can’t sprint all the way to Caemlyn. Steady!” He marched the men as quickly as he dared, nearly at a jog. Their armor clanked. Elayne had taken half of the Band with her to the Field of Merrilor, including Estean and most of the cavalry. Perhaps she had anticipated needing to withdraw quickly.

Well, Talmanes wouldn’t have much use for cavalry in the streets, which were no doubt as clogged as this roadway. Selfar snorted and shook his head. They were close now; the city walls just ahead—black in the night—held in an angry light. It was as if the city were a firepit.

By grace and banners fallen, Talmanes thought with a shiver. Enormous clouds of smoke billowed over the city. This was bad. Far worse than when the Aiel had come for Cairhien.

Talmanes finally gave Selfar his head. The roan galloped along the side of the road for a time; then Talmanes reluctantly forced his way across, ignoring pleas for help. Time he’d spent with Mat made him wish there were more he could offer these people. It was downright strange, the effect Mat-rim Cauthon had on a person. Talmanes looked at common folk in a very different light now. Perhaps it was because he still didn’t rightly know whether to think of Mat as a lord or not.

On the other side of the road, he surveyed the burning city, waiting for his men to catch up. He could have mounted all of them—though they weren’t trained cavalry, every man in the Band had a horse for long-distance travel. Tonight, he didn’t dare. With Trollocs and Myrddraal lurking in the streets, Talmanes needed his men in immediate fighting shape. Crossbowmen marched with loaded weapons at the flanks of deep columns of pike-men. He would not leave his soldiers open to a Trolloc charge, no matter how urgent their mission.

But if they lost those dragons . . .

Light illumine us, Talmanes thought. The city seemed to be boiling, with all that smoke churning above. Yet some parts of the Inner City—rising high on the hill and visible over the walls—were not yet aflame. The Palace wasn’t on fire yet. Could the soldiers there be holding?

No word had come from the Queen, and from what Talmanes could see, no help had arrived for the city. The Queen must still be unaware, and that was bad.

Very, very bad.

Ahead, Talmanes spotted Sandip with some of the Band’s scouts. The slender man was trying to extricate himself from a group of refugees.

“Please, good master,” one young woman was crying. “My child, my daughter, in the heights of the northern march . . . .”

“I must reach my shop!” a stout man bellowed. “My glasswares—”

“My good people,” Talmanes said, forcing his horse among them, “I should think that if you want us to help, you might wish to back away and allow us to reach the bloody city.”

The refugees reluctantly pulled back, and Sandip nodded to Talmanes in thanks. Tan-skinned and dark-haired, Sandip was one of the Band’s commanders and an accomplished hedge-doctor. The affable man wore a grim expression today, however.

“Sandip,” Talmanes said, pointing, “there.”

In the near distance, a large group of fighting men clustered, looking at the city.

“Mercenaries,” Sandip said with a grunt. “We’ve passed several batches of them. Not a one seemed inclined to lift a finger.”

“We shall see about that,” Talmanes said. People still flooded out through the city gates, coughing, clutching meager possessions, leading crying children. That flow would not soon slacken. Caemlyn was as full as an inn on market day; the ones lucky enough to be escaping would be only a small fraction compared to those still inside.

“Talmanes,” Sandip said quietly, “that city’s going to become a death trap soon. There aren’t enough ways out. If we let the Band become pinned inside . . .”

“I know. But—”

At the gates a wave of feeling surged through the refugees. It was almost a physical thing, a shudder. The screams grew more intense. Talmanes spun; hulking figures moved in the shadows inside the gate.

“Light!” Sandip said. “What is it?”

“Trollocs,” Talmanes said, turning Selfar. “Light! They’re going to try to seize the gate, stop the refugees.” There were five gates out of the city; if the Trollocs held all of them . . .

This was already a slaughter. If the Trollocs could stop the frightened people from fleeing, it would grow far worse.

“Hurry the ranks!” Talmanes yelled. “All men to the city gates!” He spurred Selfar into a gallop.

The building would have been called an inn elsewhere, though Isam had never seen anyone inside except for the dull-eyed women who tended the few drab rooms and prepared tasteless meals. Visits here were never for comfort. He sat on a hard stool at a pine table so worn with age, it had likely grayed long before Isam’s birth. He refrained from touching the surface overly much, lest he come away with more splinters than an Aiel had spears.

Isam’s dented tin cup was filled with a dark liquid, though he wasn’t drinking. He sat beside the wall, near enough the inn’s single window to watch the dirt street outside, dimly lit in the evening by a few rusty lanterns hung outside buildings. Isam took care not to let his profile show through the smeared glass. He never looked directly out. It was always best not to attract attention in the Town.

That was the only name the place had, if it could be said to have a name at all. The sprawling ramshackle buildings had been put up and replaced countless times over two thousand years. It actually resembled a good-sized town, if you squinted. Most of the buildings had been constructed by prisoners, often with little or no knowledge of the craft. They’d been supervised by men equally ignorant. A fair number of the houses seemed held up by those to either side of them.

Sweat dribbled down the side of Isam’s face, as he covertly watched that street. Which one would come for him?

In the distance, he could barely make out the profile of a mountain splitting the night sky. Metal rasped against metal somewhere out in the Town like steel heartbeats. Figures moved on the street. Men, heavily cloaked and hooded, with faces hidden up to the eyes behind blood-red veils.

Isam was careful not to let his eyes linger on them.

Thunder rumbled. The slopes of that mountain were filled with odd lightning bolts that struck upward toward the ever-present gray clouds. Few humans knew of this Town not so far from the valley of Thakan'dar, with Shayol Ghul itself looming above. Few knew rumors of its existence. Isam would not have minded being among the ignorant.

Another of the men passed. Red veils. They kept them up always. Well, almost always. If you saw one lower his veil, it was time to kill him. Because if you didn’t, he’d kill you. Most of the red-veiled men seemed to have no reason to be out, beyond scowling at each other and perhaps kicking at the numerous stray dogs–slat-ribbed and feral—whenever one crossed their path. The few women who had left shelter scuttled along the edges of the street, eyes lowered. There were no children to be seen, and likely few to be found. The Town was no place for children. Isam knew. He had grown from infancy here.

One of the men passing on the street looked up at Isam’s window and stopped. Isam went very still. The Samma N’Sei, the Eye Blinders, had always been touchy and full of pride. No, touchy was too mild a term. They required no more than whim to take a knife to one of the Talentless. Usually it was one of the servants who paid. Usually.

The red-veiled man continued to regard him. Isam stilled his nerves and did not make a show of staring back. His summons here had been urgent, and one did not ignore such things if one wished to live. But still . . . if the man took one step toward the building, Isam would slip into Tel’ararirhiod, secure in the knowledge that not even one of the Chosen could follow him from here.

Abruptly the Samma N’Sei turned from the window. In a flash he was moving away from the building, striding quickly. Isam felt some of his tension melt away, though it would never truly leave him, not in this place. This place was not home, despite his childhood here. This place was death.

Motion. Isam glanced toward the end of the street. Another tall man, in a black coat and cloak, was walking toward him, his face exposed. Incredibly, the street was emptying as Samma N’Sei darted off down other streets and alleys.

So it was Moridin. Isam had not been there to witness the Chosen’s first visit to the Town, but he had heard. The Samma N’Sei had thought Moridin one of the Talentless until he demonstrated differently. The constraints that held them did not hold him.

The numbers of dead Samma N’Sei varied with the telling, but the claim never dipped below a dozen. By the evidence of his eyes, Isam could believe it.

When Moridin reached the inn, the street was empty save for the dogs. And Moridin walked right on past. Isam watched as closely as he dared. Moridin seemed uninterested in him or the inn, which was where Isam had been instructed to wait. Perhaps the Chosen had other business, and Isam would be an afterthought.

After Moridin passed, Isam finally took a sip of his dark drink. The locals just called it “fire.” It lived up to its name. It was supposedly related to some drink from the Waste. Like everything else in the Town, it was a corrupt version of the original.

How long was Moridin going to make him wait? Isam didn’t like being here. It reminded him too much of his childhood. A servant passed—a woman with a dress so frayed that it was practically rags—and dropped a plate onto the table. The two didn’t exchange a word.

Isam looked at his meal. Vegetables—peppers and onions, mostly—sliced thin and boiled. He picked at one and took a taste, then sighed and pushed the meal aside. The vegetables were as bland as unseasoned millet porridge. There wasn’t any meat. That was actually good; he didn’t like to eat meat unless he’d seen it killed and slaughtered himself. That was a remnant of his childhood. If you hadn’t seen it slaughtered yourself, you couldn’t know. Not for certain. Up here, if you found meat, it could have been something that had been caught in the south, or maybe an animal that had been raised up here, a cow or a goat.

Or it could be something else. People lost games up here and couldn’t pay, then disappeared. And often, the Samma N’Sei who didn’t breed true washed out of their training. Bodies vanished. Corpses rarely lasted long enough for burial.

Burn this place, Isam thought, stomach unsettled. Burn it with—

Someone entered the inn. He couldn’t watch both approaches to the door from this direction, unfortunately. She was a pretty woman, dressed in black trimmed with red. Isam didn’t recognize her slim figure and delicate face. He was increasingly certain he could recognize all of the Chosen; he’d seen them often enough in the dream. They didn’t know that, of course. They thought themselves masters of the place, and some of them were very skilled.

He was equally skilled, and also exceptionally good at not being seen.

Whoever this was, she was in disguise, then. Why bother hiding herself here? Either way, she had to be the one who had summoned him. No woman walked the Town with such an imperious expression, such self assurance, as if she expected the rocks themselves to obey if told to jump. Isam went quietly down on one knee.

That motion woke the ache inside his stomach from where he’d been wounded. He still hadn’t recovered from the fight with the wolf. He felt a stirring inside of him; Luc hated Aybara. Unusual. Luc tended to be the more accommodating one, Isam the hard one. Well, that was how he saw himself.

Either way, on this particular wolf, they agreed. On one hand, Isam was thrilled; as a hunter, he’d rarely been presented with such a challenge as Aybara. However, his hatred was deeper. He would kill Aybara.

Isam covered a grimace at the pain and bowed his head. The woman left him kneeling and took a seat at his table. She tapped a finger on the side of the tin cup for a few moments, staring at its contents, and did not speak.

Isam remained still. Many of those fools who named themselves Dark-friends would squirm and writhe when another asserted power over them. Indeed, he admitted with reluctance, Luc would probably squirm just as much.

Isam was a hunter. That was all he cared to be. When you were secure with what you were, there was no cause to resent being shown your place.

Burn it, but the side of his belly did ache.

“I want him dead,” the woman said. Her voice was soft, yet intense.

Isam said nothing.

“I want him gutted like an animal, his bowels spilled onto the ground, his blood a milkpan for ravens, his bones left to bleach, then gray, then crack in the heat of the sun. I want him dead, hunter.”

“Al’Thor.”

“Yes. You have failed in the past.” Her voice was ice. He felt a chill. This one was hard. Hard as Moridin.

In his years of service, he had learned contempt for most of the Chosen. They bickered like children, for all their power and supposed wisdom. This woman made him pause, and he wondered if he actually had spied on all of them. She seemed different.

“Well?” she asked. “Do you speak for your failures?”

“Each time one of the others has tasked me with this hunt,” he said, “another has come to pull me away and set me on some other task.”

In truth, he’d rather have continued his hunt for the wolf. He would not disobey orders, not direct ones from the Chosen. Other than Aybara, one hunt was much the same to him as another. He would kill this Dragon, if he had to.

“Such won’t happen this time,” the Chosen said, still staring at his cup. She hadn’t looked at him, and she did not give him leave to stand, so he remained kneeling. “All others have renounced claim on you. Unless the Great Lord tells you otherwise—unless he summons you himself—you are to keep to this task. Kill al’Thor.”