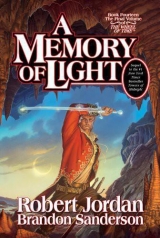

Текст книги "A Memory of Light"

Автор книги: Robert Jordan

Соавторы: Brandon Sanderson

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 71 страниц)

Elayne blinked in shock. “You would have actually done it? Just . . . left us alone? To fight?”

“Some argued for it,” Haman said.

“I myself took that position,” the woman said. “I made the argument, though I did not truly believe it was right.”

“What?” Loial asked, stumbling forward. This seemed news to him. “You didn’t?”

The woman looked to him. “Trees will not grow if the Dark One claims this world.”

Loial looked surprised. “But why did you—”

“An argument must have opposition if it is to prove itself, my son,” she said. “One who argues truly learns the depth of his commitment through adversity. Did you not learn that trees grow roots most strongly when winds blow through them?” She shook her head, though she did seem fond. “That is not to say you should have left the stedding when you did. Not alone. Fortunately, that has been taken care of.”

“Taken care of?” Perrin asked.

Loial blushed. “Well, you see, Perrin, I am married now.”

“You didn’t mention this earlier!”

“Everything has come so quickly. I am married to Erith, though, you see. She’s just over there. Did you hear her singing? Isn’t her song beautiful? Being married is not so bad, Perrin. Why didn’t you tell me it was not so bad? I think I am rather fond of it.”

“I am pleased for you, Loial,” Elayne cut in. Ogier could talk quite long on tangents if one was not careful. “And thankful, to all of you, for joining us.”

“It is worth the price, perhaps,” Haman said, “just to see these trees. In all my life, men have only cut Great Trees. To see someone growing them instead . . . We made the correct decision. Yes, yes, we did. The others will need to see this . . .”

Loial waved to Perrin, apparently wanting to catch up. “Allow me to borrow him for a moment, Loial,” Elayne said, steering Perrin toward the center of the grove.

Faile and Birgitte joined her, and Loial waited behind. He seemed distracted by the mighty trees.

“I have a duty I want to assign you,” Elayne said softly to Perrin. “Losing Caemlyn threatens to send our armies into a supply crisis. Despite complaints of food prices, we had been keeping everyone fed, as well as accumulating stores for the battle ahead. Those stores are now gone.”

“What of Cairhien?” Perrin asked.

“It still has some food,” Elayne said. “As do the White Tower and Tear. Baerlon has good supplies of metals and powder—I need to find what we can draw from the other nations, and discover their food situation. It will be a massive task to coordinate stores and rations for all the armies. I’d like one person in charge of it all.”

“You were thinking of me?” Perrin said.

“Yes.”

“I’m sorry,” Perrin said. “Elayne, Rand needs me.”

“Rand needs us all.”

“He needs me more,” Perrin said. “Min saw it, he said. Without me at the Last Battle, he’ll die. Besides, I have a few fights to finish.”

“I’ll do it,” Faile said.

Elayne turned toward her, frowning.

“It is my duty to manage the affairs of my husband’s army,” Faile said. “You are his liege lady, Your Majesty, so your needs are his needs. If Andor is to command the Last Battle, then the Two Rivers will see it fed. Give me access to gateways large enough for wagons to drive through, give me troops to protect my movements, and give me access to the quartermaster records of anyone I want. I will see it done.”

It was logical and rational, but not what Elayne needed. How far did she trust this woman? Faile had proven herself deft at politics. That was useful, but did she really consider herself part of Andor? Elayne studied the woman.

“There is nobody better you can trust with this task, Elayne,” Perrin said. “Faile will see it done.”

“Perrin,” Elayne said. “There is a different matter involved in this. May we speak privately for a moment?”

“I’ll just tell her what it is when we're done, Your Majesty,” Perrin said. “I don’t keep secrets from my wife.”

Faile smiled.

Elayne eyed the two of them, then sighed softly. “Egwene came to me during our battle preparations. There is a certain . . . item of importance to the Last Battle that she needs to be delivered.”

“The Horn of Valere,” Perrin said. “You still have it, I hope.”

“We do. In the Tower, hidden. We moved it from the strongroom none too quickly. Last night, that room was broken into. I know only because of certain wards we set. The Shadow knows we have the Horn, Perrin, and the Dark One’s minions are looking for it. They can’t use it; it’s tied to Mat until he dies. But if the Shadow’s minions can capture it, he can keep Mat from using it. Or, worse—kill him, then blow it themselves.”

“You want to mask moving it,” Faile said, “using the supply runs to hide where you’re taking it.”

“We’d rather just give it to Mat straight out,” Elayne said. “But he can be . . . difficult, sometimes. I had hoped he would be here at this meeting.”

“He’s in Ebou Dar,” Perrin said. “Doing something with the Seanchan.

“He told you?” Elayne asked.

“Not exactly,” Perrin said, looking uncomfortable. “We . . . have some kind of connection. I sometimes see where he is and what he’s doing.”

“That man,” Elayne said, “is never where he needs to be.”

“And yet,” Perrin said, “he always arrives there eventually.”

“The Seanchan are the enemy,” Elayne said. “Mat doesn’t seem to understand that, considering what he’s done. Light, I hope that man isn’t putting himself in trouble somehow . . .”

“I will do this,” Faile said. “I’ll care for the Horn of Valere. I’ll see it gets to Mat, guard it.”

“No offense to either of you,” Elayne said, “but I am hesitant to trust this to someone I don’t know well. That is why I came to you, Perrin.”

“That’s going to be a problem, Elayne,” Perrin said. “If they really are watching for the Horn, then they’ll expect you and Egwene to give it to someone you know well. Choose Faile. There is nobody I trust more than her, but she won’t be suspected, as she has no direct relationship with the White Tower.”

Elayne nodded slowly. “Very well. I’ll send word to you on how it will be delivered. For now, begin running supplies to establish precedent. Too many people know about the Horn. After we give it to you, I will send five suspect envoys from the White Tower and seed the right rumors. We hope that the Shadow will assume the Horn is being carried by one of those envoys. I want it to be where nobody expects, at least until we can put it into Matrim’s hands.”

“Four battlefronts, Lord Mandragoran,” Bulen repeated. “That’s what the messengers are saying. Caemlyn, Shayol Ghul, Kandor, and here. They want to try to bottle up the Trollocs here and in Kandor while trying hard to defeat those in Andor first.”

Lan grunted, guiding Mandarb around the reeking heap of dead Trollocs. The carcasses served as a bulwark now that his five Asha’man had pushed them up into mounds like dark, bloody hills before the Blight, where the Shadowspawn gathered.

The stench was horrible, of course. Many of the guards he passed in his rounds had thrown sprigleaf onto their fires to cover up the smell.

Evening approached, bringing its most dangerous hours. Fortunately, those black clouds above made nights so dark that Trollocs had trouble seeing anything. Dusk, however, was a time of strength to them—a time when the eyes of humans were hampered but the eyes of Shadowspawn were not.

The power of the united Borderlander attack had pushed the Trollocs back toward the mouth of the Gap. Lan was getting reinforced by the hour with pikemen and other foot to help him hold position. All in all, it looked far better here now than it had just a day before.

Still grim, though. If what Bulen said was right, his army would be stationed here as a stalling force. That meant fewer troops for him than he would have liked. He could not fault the tactics presented, however.

Lan passed into the area where the Shienaran lancers cared for their horses. A figure emerged from them and rode up beside Lan. King Easar was a compact man with a white topknot, recently arrived from the Field of Merrilor following a long day making battle plans. Lan began a horseback bow, but stopped as King Easar bowed to him.

“Your Majesty?” Lan asked.

“Agelmar has brought his plans for this battlefront, Dai Shan,” King Easar said, falling in beside him. “He would like to go over them with us. It is important that you are there; we fight beneath the banner of Malkier. We all agreed to it.”

“Tenobia?” Lan asked, genuinely surprised.

“In her case, a little encouragement was required. She came around. I also have word that Queen Ethenielle will leave Kandor and come here. The Borderlands fight together in this battle, and we do it with you at our head.”

They rode on in the fading light, row upon row of lancers saluting Easar. The Shienarans were the finest heavy cavalry in the world, and they had fought—and died—upon these rocks countless times, defending the lush lands to the south.

“I will come,” Lan agreed. “The weight of what you have given me feels like three mountains.”

“I know,” Easar said. “But we shall follow you, Dai Shan. Until the sky is rent asunder, until the rocks split underfoot, and until the Wheel itself stops turning. Or, Light send its blessing, until every sword is favored with peace.”

“What of Kandor? If the Queen comes here, who will lead that battle?”

“The White Tower rides to fight the Shadowspawn there,” Easar said. “You raised the Golden Crane. We were sworn to come to your aid, so we have.” He hesitated, and then his voice grew grim. “Kandor is beyond recovery now, Dai Shan. The Queen admits it. The White Towers job is not to recover it, but to stop the Shadowspawn from taking more territory.”

They turned and rode through the ranks of lancers. The men were required to spend dusk within a few paces of their mounts, and they made themselves busy, caring for armor, weapons and horses. Each man wore a longsword, sometimes two, strapped to his back, and all had maces and daggers at their belts. The Shienarans did not rely solely upon their lances; an enemy who thought to pin them without room to charge soon discovered that they could be very dangerous in close quarters.

Most of the men wore yellow surcoats over their plate-and-mail, bearing the black hawk. They gave their salutes with stiff backs and serious faces. Indeed, the Shienarans were a serious people. Living in the Borderlands did that.

Lan hesitated, then spoke in a loud voice. “Why do we mourn?”

The soldiers nearby turned toward him.

“Is this not what we have trained for?” Lan shouted. “Is this not our purpose, our very lives? This war is not a thing to mourn. Other men may have been lax, but we have not been. We are prepared, and so this is a time of glory.

“Let there be laughter! Let there be joy! Let us cheer the fallen and drink to our forefathers, who taught us well. If you die on the morrow, awaiting your rebirth, be proud. The Last Battle is upon us, and we are ready!”

Lan wasn’t sure, exactly, what had made him say it. His words inspired a round of “Dai Shan! Dai Shan! Forward the Golden Crane!” He saw that some of the men were writing the speech down, to pass among the other men.

“You do have the soul of a leader, Dai Shan,” Easar said as they rode on.

“It is not that,” Lan said, eyes forward. “I cannot stand self-pity. Too many of the men looked as if they were preparing their own shrouds.”

“A drum with no head,” Easar said softly, flicking his horse’s reins. “A pump with no grip. A song with no voice. Still it is mine. Still it is mine.”

Lan turned, frowning, but the King gave no explanation for the poem. If his people were a serious people, their king was more so. Easar had wounds deep within that he chose not to share. Lan did not fault him in this; Lan himself had done the same.

Tonight, however, he caught Easar smiling as he considered whatever it was that had brought the poem to his lips.

“Was that Anasai of Ryddingwood?” Lan asked.

Easar looked surprised. “You have read Anasai’s work?”

“She was a favorite of Moiraine Sedai. It sounded as though it might be hers.”

“Each of her poems was written as an elegy,” Easar said. “This was for her father. She left instructions; it can be read, but should not be spoken out loud, except when it was right to do so. She did not explain when it would be right to do so.”

They reached the war tents and dismounted. No sooner had they done so, however, than the horns of alarm began to sound. Both men reacted, and Lan unconsciously touched the sword on his hip.

“Let us go to Lord Agelmar,” Lan shouted as men began to yell and equipment to rattle. “If you fight beneath my banner, then I will accept the role of leader gladly.”

“No hesitation at all?” Easar said.

“What am I?” Lan asked, swinging into the saddle. “Some sheepherder from a forgotten village? I will do my duty. If men are foolish enough to put me in charge of them, I’ll send them about theirs as well.”

Easar nodded, then saluted, the corners of his mouth rising in another smile. Lan returned the salute, then galloped Mandarb through the center of the camp. The men at the outskirts were lighting bonfires; Ashaman had created gateways to one of the many dying forests in the south for soldiers to gather wood. If Lan had his way, those five channelers would never waste their strength killing Trollocs. They were far too useful otherwise.

Narishma saluted Lan as he passed. Lan could not be certain that the great captains had chosen Borderlander Ashaman for him on purpose, but it seemed not to be a coincidence. He had at least one from each Borderlander nation—even one born to Malkieri parents.

We fight together.

CHAPTER 8

That Smoldering City

Atop Moonshadow, her deep brown mare from the royal stables, Elayne Trakand rode through a gateway of her own making.

Those stables were now in the hands of Trollocs, and Moonshadow’s stablemates had undoubtedly found their way into cookpots by now. Elayne did not think too hard about what else—who else—might have ended up in those same pots. She set her face in determination. Her troops would not see their queen look uncertain.

She had chosen to come to a hill about a thousand paces to the northwest of Caemlyn, well out of bow range but close enough to see the city. Several mercenary bands had made their camp in these hills during the weeks following the Succession War. Those had all either joined the armies of Light or had disbanded, becoming roving thieves and brigands.

The foreguard had already secured the area, and Captain Guybon saluted as members of the Queens Guard—both male and female—surrounded Elayne’s horse. The air still smelled of smoke, and seeing Caemlyn smoldering like Dragonmount itself tossed a handful of bitter powder into the stew of emotions churning inside of her.

The once-proud city was dead, a pyre that pitched a hundred different columns of smoke toward the storm clouds above. The smoke reminded her of the spring burnings, when farmers would occasionally fire their fields to help clear them for planting. She hadn’t ruled Caemlyn for a hundred days, and already it was lost.

If dragons can do that to a city, she thought, surveying the hole that Talmanes had made in the nearest wall, the world will need to change. Everything we know about warfare will change.

“How many, would you say?” she asked the man who rode up beside her. Talmanes was only one day of rest away from the ordeal that should have cost him his life. He probably should have remained at Merrilor; he certainly wouldn’t be doing any frontline fighting in the near future.

“It is impossible to count their numbers, hidden as they are in the city, Your Majesty,” he said, bowing respectfully. “Tens of thousands, but probably not hundreds of thousands.”

The fellow was nervous around her, and he manifested it in a very Cairhienin way—by speaking with flowery respect. He was said to be one of Mat’s most trusted officers; she would have assumed that, by now, Mat would have corrupted the fellow far more. He didn’t curse once. Pity.

Other gateways opened nearby onto the yellow grass, and her forces came through, filling the fields and topping the hills. She had taken charge of a large army of warriors, which included many of the siswai’aman, to bolster her Queen’s Guard and the Andoran regulars under the command of Birgitte and Captain Guybon. A second contingent of Aiel—Maidens, Wise Ones and the remaining warriors—had been chosen to travel north to Shayol Ghul with Rand.

Only a handful of Wise Ones had come with Elayne, the ones who followed Perrin. Elayne would have liked more channelers than that. Still, she did have the Band and their dragons, which should make up for the fact that her only other channelers were the Kinswomen, many of whom were on the weaker side of strength in the Power.

Perrin and his force had come with her. That included Mayene’s Winged Guards, the Ghealdanin cavalry, the Whitecloaks—she still wasn’t sure what she thought of that—and a company of Two Rivers archers with Tam. Filling out her army was the group who called themselves the Wolf Guard, mostly refugees turned soldiers, some of whom had received combat training. And, of course, she had Captain Bashere and his Legion of the Dragon.

She had approved Bashere’s plan for the battle at Caemlyn. We will need to draw the fighting into the woods, he had explained. The archers will be deadly, loosing at the Trollocs upon their approach. If these lads can move as well as I am told they can in the forest, they’ll be just as dangerous once they’ve pulled back.

The Aiel, too, would be deadly in a forest, where the Trollocs wouldn’t be able to use their masses to overrun their opponents. Bashere himself rode nearby. Apparently, Rand had specifically told him to watch over her. As if she didn’t have Birgitte jumping every time she moved.

Rand had better stay safe so I can tell him what I think of him, she thought as Bashere approached in quiet conversation with Birgitte. Bashere was a bowlegged man with a thick mustache. He didn’t talk to Elayne the way a man should a queen . . . but then, the Queen of Saldaea was his niece, so perhaps he was just very comfortable around royalty.

He is first in line for the throne, Elayne reminded herself. Working with him would offer opportunities to further secure her ties to Saldaea. She still liked the idea of seeing one of her children on that throne. She lowered a hand to her stomach. The babes kicked and elbowed frequently now. Nobody had told her it would feel so much like . . . well, indigestion. Unfortunately, Melfane had, against all expectation, found some goat’s milk.

“What word?” Elayne asked as Birgitte and Bashere arrived, Talmanes moving his horse aside to make room.

“Scout reports of the city are in,” Bashere said.

“Bashere was right,” Birgitte said. “The Trollocs have been reined in, and the burning has mostly died out. A good half of the city still stands. Much of that smoke you see is from cook fires, not buildings.”

“Trollocs are stupid,” Bashere said, “but Halfmen are not. The Trollocs would have gleefully ransacked the city and lit fires all across it, but that would have threatened to let the fires get away from them. Either way, the truth is we don’t know what the Shadow is planning here, but they at least have the option of trying to hold the city for a time, should they desire.”

“Will they try that?” Elayne asked.

“I can’t say, honestly,” Bashere replied. “We don’t know their goals. Was this attack on Caemlyn intended to sow chaos and bring fear to our armies, or is it intended to take a stronghold and hold it long-term as a base from which to harry our forces? Back during the Trolloc Wars, the Fades did hold cities for that purpose.”

Elayne nodded.

“Pardon, Your Majesty?” a voice said. She turned to see one of the Two Rivers men stepping up. One of their leaders, Tam’s second-in-command. Dannil, she thought, that's his name.

“Your Majesty,” Dannil repeated. He fumbled a little, but actually spoke with some polish. “Lord Goldeneyes has his men set up in the forest.”

“Lord Talmanes, do you have your dragons in position?”

“Almost,” Talmanes said. “Pardon, Your Majesty, but I’m not certain the bows will be needed once those weapons fire. Are you certain you don’t want to lead with the dragons?”

“We need to goad the Trollocs into battle,” Elayne said. “The placement I outlined will work best. Bashere, what of my plan for the city itself?”

“I think everything is almost ready, but I’ll want to check,” Bashere said, knuckling his mustache in thought. “Those women of yours made gateways well enough, and Mayene gave us the oil. You’re sure you want to go through with something so drastic?”

“Yes.”

Bashere waited for more of a response, perhaps an explanation. When she didn’t give one, he moved off, issuing the last orders. Elayne turned Moonshadow to ride down the ranks of soldiers here at the front lines, where they’d set up near the forests. There wasn’t much she could do now, in these last moments as her commanders gave orders, but she could be seen riding with confidence. Where she passed, the men raised their pikes higher, lifted their chins.

Elayne kept her own eyes on that smoldering city. She would not look away, and she would not let anger control her. She would use the anger.

Bashere returned to her a short time later. “It’s done. The basements of many buildings that are still standing have been filled with oil. Talmanes and the others are in place. Once your Warder returns with word that the Kinswomen are prepared to open another round of gateways, we can proceed.”

Elayne nodded, and then removed her hand from her belly as Bashere glanced at it. She hadn’t realized she’d been holding it again. “What do you think of me going to battle while pregnant? Is it a mistake?”

He shook his head. “No. It proves just how desperate our situation is. It will make the soldiers think. Make them more serious. Besides . . .

“What?”

Bashere shrugged. “Perhaps it will remind them that not everything in this world is dying.”

Elayne turned back, looking at the distant city. Farmers burned their fields in the spring to prepare them for new life. Maybe that was what Andor was suffering now.

“Tell me,” Bashere said. “Are you going to tell the men that you’re carrying the Lord Dragon’s child?”

Children, Elayne corrected in her head. “You presume to know something that may or may not be true, Lord Bashere.”

“I have a wife, and a daughter. I recognize the look in your eyes when you see the Lord Dragon. No woman with child touches her hand to her womb so reverently when looking on a man who is not the father.”

Elayne drew her lips into a line.

“Why do you hide it?” Bashere asked. “I’ve heard what some of the men think. They talk of some other man, a Darkfriend named Mellar, once Captain of your Guardswomen. I can see that the rumors are false, but others are not so wise. You could kill those rumors if you wished.”

“Rand’s children will be targets,” she said.

“Ah . . .” he replied. He knuckled his mustache for a moment.

“If you disagree with the reasoning, Bashere, speak your mind. I will not suffer a toady.”

“I’m no toady, woman,” he said with a huff. “But regardless, I hardly doubt your child could be a greater target than he or she already is. You’re high commander of the armies of the Light! I think your men deserve to know what exactly they’re fighting for.”

“It is not your business to know,” Elayne said, “nor is it theirs.”

Bashere raised an eyebrow at her. “The heir to the realm,” he said flatly, “is not the business of its subjects?”

“I believe you are overstepping your bounds, General.”

“Perhaps I am,” he said. “Maybe spending so much time with the Lord Dragon has warped the way I do things. That man . . . you could never tell what he was thinking. Half of the time, he wanted to hear my mind, as raw as I could lay it out. The other half of the time, it seemed like he’d break me in two just for commenting that the sky looked a little dark.” Bashere shook his head. “Just give it some thought, Your Majesty. You remind me of my daughter. She might have done something similar, and this is the advice I’d give her. Your men will fight more bravely if they know that you carry the Dragon Reborns heir.”

Men, Elayne thought. The young ones try to impress me with every stunt that comes into their fool heads. The old ones assume every young woman is in need of a lecture.

She turned her eyes toward the city again as Birgitte rode up and gave her a nod. The basements were filled with oil and pitch.

“Burn it,” Elayne said loudly.

Birgitte waved a hand. The Kinswomen opened their round of gateways, and men hurled lit torches through into the basements of Caemlyn. It didn’t take long for the smoke rising above the city to grow darker, more ominous.

“They won’t soon put that out,” Birgitte said softly. “Not with the dry weather we’ve been having. The entire city will go up like a haystack.”

The army gathered to stare at the city, particularly the members of the Queen’s Guard and the Andoran military. A few of them saluted, as one might salute the pyre of a fallen hero.

Elayne ground her teeth, then said, “Birgitte, make it known among the Guards. The children I carry were fathered by the Dragon Reborn.”

Bashere’s smile deepened. Insufferable man! Birgitte was smiling as she went to spread the word. She was insufferable, too.

The men of Andor seemed to stand taller, prouder, as they watched their capital burn. Trollocs started pouring from the gates, driven by the fires. Elayne made sure the Trollocs saw her army, then announced, “Northward!” She turned Moonshadow. “Caemlyn is dead. We take to the forests; let the Shadowspawn follow!”

Androl awoke with dirt in his mouth. He groaned, trying to roll over, but found himself bound in some way. He spat, licked his lips and blinked crusty eyes.

He lay with Jonneth and Emarin against an earthen wall, tied by ropes. He remembered . . . Light! The roof had fallen in.

Pevara? he sent. Incredible how natural that method of communication was beginning to feel.

He was rewarded with a groggy sensation from her. The bond let him know that she was nearby, probably tied up as well. The One Power was also lost to him; he clawed at it, but ran up against a shield. His bonds were tied to some kind of hook in the ground behind him, hindering his movement.

Androl shoved panic down with some effort. He couldn’t see Nalaam. Was he here? The group of them lay tied in a large chamber, and the air smelled of damp earth. They were still underground in a part of Taim’s secret complex.

If the roof fell in, Androl thought, the cells were probably destroyed. That explained why he and the others were tied up, but not locked away.

Someone was sobbing.

He strained around and found Evin tied nearby. The younger man wept, shaking.

“It’s all right, Evin,” Androl whispered. “We’ll find a way out of this.”

Evin glanced at him, shocked. The youth was tied in a different way, in a seated position, hands behind his back. “Androl? Androl, I’m sorry.”

Androl felt a twisting emotion. “For what, Evin?”

“They came right after the rest of you left. They wanted Emarin, I think. To Turn him. When he wasn’t there, they began asking questions, demands. They broke me, Androl. I broke so easily. I’m sorry . . .”

So Taim hadn’t discovered the fallen guards. “It’s not your fault, Evin.”

Footsteps sounded on the ground nearby. Androl feigned unconsciousness, but someone kicked him. “I saw you talking, pageboy,” Mishraile said, leaning down his golden-haired head. “I’m going to enjoy killing you for what you did to Coteren.”

Androl opened his eyes and saw Logain sagging in the grip of Mezar and Welyn. They dragged him near and dropped him roughly to the ground. Logain stirred and groaned as they tied him up. They stood, and one spat on Androl before moving over to Emarin.

“No,” Taim said from somewhere near. “The youth is next. The Great Lord demands results. Logain is taking too long.”

Evin’s sobs grew louder as Mezar and Welyn moved over to seize him under the arms.

“No!” Androl said, twisting. “No! Taim, burn you! Leave him alone! Take me!”

Taim stood nearby, hands clasped behind his back, in a sharp black uniform that resembled those of the Asha’man, but trimmed with silver. He wore no pins at his neck. He turned toward Androl, then sneered. “Take you? I am to present to the Great Lord a man who couldn’t channel enough to break a pebble? I should have culled you long ago.”

Taim followed the other two, who were dragging away the frantic Evin. Androl screamed at them, yelling until he was hoarse. They took Evin somewhere on the other side of the chamber—it was very large—and Androl could not see them because of the angle at which he was tied. Androl dropped his head back against the floor, closing his eyes. That didn’t prevent him from hearing poor Evin’s screams of terror.

“Androl?” Pevara whispered.

“Quiet.” Mishraile’s voice was followed by a thump and a grunt from Pevara.

I am really starting to hate that one, Pevara sent to him.

Androl didn’t reply.

They took the effort to dig us out of the collapsed room, Pevara continued. I remember some of it, before they shielded me and knocked me unconscious. It seems to have been less than a day since then. I guess Taim hasn’t yet hit his quota of Dread-lords Turned to the Shadow.

She sent it, almost, with levity.

Behind them, Evin’s screams stopped.

Oh, Light! Pevara sent. Was that Evin? All wryness vanished from her tone. What’s happening?

They’re Turning him, Androl sent back. Strength of will has something to do with resisting. That is why Logain hasn’t been Turned yet.

Pevara’s concern was a warmth through the bond. Were all Aes Sedai like her? He’d assumed they had no emotions, but Pevara felt the full range—although she accompanied it with an almost inhuman control over how those emotions affected her. Another result of decades of practice?

How do we escape? she sent.

I’m trying to untie my bonds. My fingers are stiff.

I can see the knot. It’s a hefty one, but I might be able to guide you.

He nodded, and they began, Pevara describing the turns of the knot as Androl tried to twist his fingers around them. He failed to get enough purchase on the bonds; he tried pulling his hands free and wiggling them out, but the ropes were too tight.