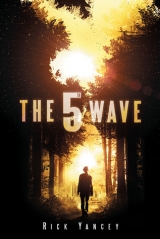

Текст книги "The 5th Wave"

Автор книги: Rick Yancey

Жанры:

Подростковая литература

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 27 страниц)

I DEBATED WHETHER to travel by day or night for a long time. Darkness is best if you’re worried about them. But daylight is preferable if you want to spot a drone before it spots you.

The drones showed up at the tag end of the 3rd Wave. Cigar-shaped, dull gray in color, gliding swiftly and silently thousands of feet up. Sometimes they streak across the sky without stopping. Sometimes they circle overhead like buzzards. They can turn on a dime and come to a sudden stop, from Mach 2 to zero in less than a second. That’s how we knew the drones weren’t ours.

We knew they were unmanned (or un-Othered) because one of them crashed a couple miles from our refugee camp. A thu-whump! when it broke the sound barrier, an ear-piercing shriek as it rocketed to earth, the ground shuddering under our feet when it plowed into a fallow cornfield. A recon team hiked to the crash site to check it out. Okay, it wasn’t really a team, just Dad and Hutchfield, the guy in charge of the camp. They came back to report the thing was empty. Were they sure? Maybe the pilot bailed before impact. Dad said it was packed with instruments; there wasn’t any room for a pilot. “Unless they’re two inches tall.” That got a big laugh. Somehow it made the horror less horrible, thinking of the Others as being two-inch Borrower types.

I opted to travel by day. I could keep one eye on the sky and another on the ground. What I ended up doing is rocking my head up and down, up and down, side to side, then up again, like some groupie at a rock concert, until I was dizzy and a little sick to my stomach.

Plus there are other things at night to worry about besides drones. Wild dogs, coyotes, bears, and wolves coming down from Canada, maybe even an escaped lion or tiger from a zoo. I know, I know, there’s a Wizard of Oz joke buried in there. Shoot me.

And though it wouldn’t be much better, I do think I’d have a better chance against one of them in the daylight. Or even against one of my own, if I’m not the last one. What if I stumble onto another survivor who decides the best course of action is to go all Crucifix Soldier on anyone they come across?

That brings up the problem of my best course of action. Do I shoot on sight? Do I wait for them to make the first move and risk it being a deadly one? I wonder, not for the first time, why the hell we didn’t come up with some kind of code or secret handshake or something before they showed up—something that would identify us as the good guys. We had no way of knowing they would show up, but we were pretty sure something would sooner or later.

It’s hard to plan for what comes next when what comes next is not something you planned for.

Try to spot them first, I decided. Take cover. No showdowns. No more Crucifix Soldiers!

The day is bright and windless but cold. The sky cloudless. Walking along, bobbing my head up and down, swinging it from side to side, backpack popping against one shoulder blade, the rifle against the other, walking on the outside edge of the median that separates the southbound from the northbound lanes, stopping every few strides to whip around and scan the terrain behind me. An hour. Two. And I’ve traveled no more than a mile.

The creepiest thing, creepier than the abandoned cars and the snarl of crumpled metal and the broken glass sparkling in the October sunlight, creepier than all the trash and discarded crap littering the median, most of it hidden by the knee-high grass so the strip of land looks lumpy, covered in boils, the creepiest thing is the silence.

The Hum is gone.

You remember the Hum.

Unless you grew up on top of a mountain or lived in a cave your whole life, the Hum was always around you. That’s what life was. It was the sea we swam in. The constant sound of all the things we built to make life easy and a little less boring. The mechanical song. The electronic symphony. The Hum of all our things and all of us. Gone.

This is the sound of the Earth before we conquered it.

Sometimes in my tent, late at night, I think I can hear the stars scraping against the sky. That’s how quiet it is. After a while it’s almost more than I can stand. I want to scream at the top of my lungs. I want to sing, shout, stamp my feet, clap my hands, anything to declare my presence. My conversation with the soldier had been the first words I’d said aloud in weeks.

The Hum died on the tenth day after the Arrival. I was sitting in third period texting Lizbeth the last text I will ever send. I don’t remember exactly what it said.

Eleven A.M. A warm, sunny day in early spring. A day for doodling and dreaming and wishing you were anywhere but Ms. Paulson’s calculus class.

The 1st Wave rolled in without much fanfare. It wasn’t dramatic. There was no shock and awe.

The lights just winked out.

Ms. Paulson’s overhead died.

The screen on my phone went black.

Somebody in the back of the room squealed. Classic. It doesn’t matter what time of day it happens—the power goes out, and somebody yelps like the building’s collapsing.

Ms. Paulson told us to stay in our seats. That’s the other thing people do when the power goes out. They jump up to…To what? It’s weird. We’re so used to electricity, when it’s gone, we don’t know what to do. So we jump up or squeal or start jabbering like idiots. We panic. It’s like someone cut off our oxygen. The Arrival had made it worse, though. Ten days on pins and needles waiting for something to happen while nothing is happening makes you jumpy.

So when they pulled the plug on us, we freaked a little more than normal.

Everybody started talking at once. When I announced that my phone had died, out came everyone’s dead phone. Neal Croskey, who was sitting in the back of the room listening to his iPod while Ms. Paulson lectured, pulled the buds from his ears and wondered aloud why the music had died.

The next thing you do when the plug’s pulled, after panicking, is run to the nearest window. You don’t know why exactly. It’s that better-see-what’s-going-on feeling. The world works from the outside in. So if the lights go off, you look outside.

And Ms. Paulson, randomly moving around the mob milling in front of the windows: “Quiet! Back to your seats. I’m sure there’ll be an announcement…”

There was one, about a minute later. Not over the intercom, though, and not from Mr. Faulks, the vice principal. It came from the sky, from them. In the form of a 727 tumbling end over end to the Earth from ten thousand feet until it disappeared behind a line of trees and exploded, sending up a fireball that reminded me of the mushroom cloud of an atomic blast.

Hey, Earthlings! Let’s get this party started!

You’d think seeing something like that would send us diving under our desks. It didn’t. We crowded against the window and scanned the cloudless sky for the flying saucer that must have taken the plane down. It had to be a flying saucer, right? We knew how a top-notch alien invasion was run. Flying saucers zipping through the atmosphere, squadrons of F-16s hot on their heels, surface-to-air missiles and tracers screaming from the bunkers. In an unreal and admittedly sick way, we wanted to see something like that. It would make this a perfectly normal alien invasion.

For a half hour we waited by the windows. Nobody said much. Ms. Paulson told us to go back to our seats. We ignored her. Thirty minutes into the 1st Wave and already social order was breaking down. People kept checking their phones. We couldn’t connect it: the plane crashing, the lights going out, our phones dying, the clock on the wall with the big hand frozen on the twelve, little hand on the eleven.

Then the door flew open and Mr. Faulks told us to head over to the gym. I thought that was really smart. Get all of us in one place so the aliens didn’t have to waste a lot of ammunition.

So we trooped over to the gym and sat in the bleachers in near total darkness while the principal paced back and forth, stopping every now and then to yell at us to be quiet and wait for our parents to get there.

What about the students whose cars were at school? Couldn’t they leave?

“Your cars won’t work.”

WTF? What does he mean, our cars won’t work?

An hour passed. Then two. I sat next to Lizbeth. We didn’t talk much, and when we did, we whispered. We weren’t afraid of the principal; we were listening. I’m not sure what we were listening for, but it was like that quiet before the clouds open up and the thunder smashes down.

“This could be it,” Lizbeth whispered. She rubbed her nose nervously. Dug her lacquered nails into her dyed blond hair. Tapped her foot. Rolled the pad of her finger over her eyelid: She had just started wearing contacts and they bugged her constantly.

“It’s definitely something,” I whispered back.

“I mean, this could be it. Like it it. The end.”

She kept slipping the battery out of her phone and putting it back in. It was better than doing nothing, I guess.

She started to cry. I took her phone away and held her hand. Looked around. She wasn’t the only one crying. Other kids were praying. And others were doing both, crying and praying. The teachers were huddled up by the gym doors, forming a human shield in case the creatures from outer space decided to storm the floor.

“There’s so much I wanted to do,” Lizbeth said. “I’ve never even…” She choked back a sob. “You know.”

“I’ve got a feeling a lot of ‘you know’ is going on right now,” I said. “Probably right underneath these bleachers.”

“You think?” She wiped her cheeks with the palm of her hand. “What about you?”

“About ‘you know’?” I had no problem with talking about sex. My problem was talking about sex as it related to me.

“Oh, I know you haven’t ‘you know.’ God! I’m not talking about that.”

“I thought we were.”

“I’m talking about our lives, Cassie! Jesus, this could be the end of the freakin’ world, and all you want to do is talk about sex!”

She pulled her phone out of my hand and fumbled with the battery cover.

“Which is why you should just tell him,” she said, fiddling with the drawstrings of her hoodie.

“Tell who what?” I knew exactly what she meant; I was just buying time.

“Ben! You should tell him how you feel. How you’ve felt since the third grade.”

“This is a joke, right?” I felt my face getting hot.

“And then you should have sex with him.”

“Lizbeth, shut up.”

“It’s the truth.”

“I haven’t wanted to have sex with Ben Parish since the third grade,” I whispered. The third grade? I glanced over at her to see if she was really listening. Apparently, she wasn’t.

“If I were you, I’d go right up to him and say, ‘I think this is it. This is it, and I’ll be damned if I’m going to die in this school gymnasium without ever having sex with you.’ And then you know what I’d do?”

“What?” I was fighting back a laugh, picturing the look on his face.

“I’d take him outside to the flower garden and have sex with him.”

“In the flower garden?”

“Or the locker room.” She waved her hand around frantically to include the entire school—or maybe the whole world. “It doesn’t matter where.”

“The locker room smells.” I looked two rows down at the outline of Ben Parish’s gorgeous head. “That kind of thing only happens in the movies,” I said.

“Yeah, totally unrealistic, not like what’s happening right now.”

She was right. It was totally unrealistic. Both scenarios, an alien invasion of the Earth and a Ben Parish invasion of me.

“At least you could tell him how you feel,” she said, reading my mind.

Could, yes. Ever would, well…

And I never did. That was the last time I saw Ben Parish, sitting in that dark, stuffy gymnasium (Home of the Hawks!) two rows down from me, and only the back part of him. He probably died in the 3rd Wave like almost everybody else, and I never told him how I felt. I could have. He knew who I was; he sat behind me in a couple of classes.

He probably doesn’t remember, but in middle school we rode the same bus, and there was an afternoon when I overheard him talking about his little sister being born the day before and I turned around and said, “My brother was born last week!” And he said, “Really?” Not sarcastic, but like he thought it was a cool coincidence, and for about a month I went around thinking we had this special connection based on babies. Then we were in high school and he became the star wide receiver for the team and I became just another girl watching him score from the stands. I would see him in class or in the hallway, and sometimes I had to fight the urge to run up to him and say, “Hi, I’m Cassie, the girl from the bus. Do you remember the babies?”

The funny thing is, he probably would have. Ben Parish couldn’t be satisfied with being the most gorgeous guy in school. Just to torment me with his perfection, he also insisted on being one of the smartest. And have I mentioned he was kind to small animals and children? His little sister was on the sidelines at every game, and when we took the district title, Ben ran straight to the sidelines, hoisted her onto his shoulders, and led the parade around the track with her waving to the crowd like a homecoming queen.

Oh, and one more thing: his killer smile. Don’t get me started.

After another hour in the dark and stuffy gym, I saw my dad appear in the doorway. He gave a little wave, like he showed up at my school every day to take me home after alien attacks. I hugged Lizbeth and told her I’d call as soon as the phones started working again. I was still practicing pre-invasion thinking. You know, the power goes out, but it always comes back on. So I just gave her a hug and I don’t remember telling her that I loved her.

We went outside and I said, “Where’s the car?”

And Dad said the car wasn’t working. No cars were working. The streets were littered with stalled-out cars and buses and motorcycles and trucks, smashups and clusters of wrecks on every block, cars folded around light poles and sticking out of buildings. A lot of people were trapped when the EMP hit; the automatic locks on the doors didn’t work, and they had to break out of their own cars or sit there and wait for someone to rescue them. The injured people who could still move crawled onto the roadside and sidewalks to wait for the paramedics, but no paramedics came because the ambulances and the fire trucks and the cop cars didn’t work, either. Everything that ran on batteries or electricity or had an engine died at eleven A.M.

Dad walked as he talked, keeping a tight grip on my wrist, like he was afraid something might swoop down out of the sky and snatch me away.

“Nothing’s working. No electricity, no phones, no plumbing…”

“We saw a plane crash.”

He nodded. “I’m sure they all did. Anything and everything in the sky when it hit. Fighter jets, helicopters, troop transports…”

“When what hit?”

“EMP,” he said. “Electromagnetic pulse. Generate one large enough and you knock out the entire grid. Power. Communications. Transportation. Anything that flies or drives is zapped out.”

It was a mile and a half from my school to our house. The longest mile and a half I’ve ever walked. It felt as if a curtain had fallen over everything, a curtain painted to look exactly like what it was hiding. There were glimpses, though, little peeks behind the curtain that told you something had gone very wrong. Like all the people standing on their front porches holding their dead phones, looking up at the sky, or bending over the open hoods of their cars, fiddling with wires, because that’s what you do when your car dies—you fiddle with wires.

“But it’s okay,” he said, squeezing my wrist. “It’s okay. There’s a good chance our backup systems weren’t crippled, and I’m sure the government has a contingency plan, protected bases, that sort of thing.”

“And how does pulling our plug fit into their plan to help us along in the next stage of our evolution, Dad?”

I regretted the words the instant I said them. But I was freaking out. He didn’t take it the wrong way. He looked at me and smiled reassuringly and said, “Everything’s going to be okay,” because that’s what I wanted him to say and it’s what he wanted to say and that’s what you do when the curtain is falling—you give the line that the audience wants to hear.

AROUND NOON on my mission to keep my promise, I stop for a water break and a Slim Jim. Every time I eat a Slim Jim or a can of sardines or anything prepackaged, I think, Well, there’s one less of that in the world. Whittling away the evidence of our having been here one bite at a time.

One of these days, I’ve decided, I’m going to work up the nerve to catch a chicken and wring its delicious neck. I would kill for a cheeseburger. Honestly. If I stumbled across someone eating a cheeseburger, I would kill them for it.

There are plenty of cows around. I could shoot one and carve it up with my bowie knife. I’m pretty sure I’d have no problem slaughtering a cow. The hard part would be cooking it. Having a fire, even in daylight, was the surest way to invite them to the cookout.

A shadow shoots across the grass a dozen yards in front of me. I jerk my head back, knocking it hard against the side of a Honda Civic I was leaning against while I enjoyed my snack. It wasn’t a drone. It was a bird, a seagull of all things, skimming along with barely a flick of its outstretched wings. A shiver of revulsion goes down my spine. I hate birds. I didn’t before the Arrival. I didn’t after the 1st Wave. I didn’t after the 2nd Wave, which really didn’t affect me that much.

But after the 3rd Wave, I hated them. It wasn’t their fault, I knew that. It was like a man in front of a firing squad hating the bullets, but I couldn’t help it.

Birds suck.

AFTER THREE DAYS on the road, I’ve determined that cars are pack animals.

They prowl in groups. They die in clumps. Clumps of smashups. Clumps of stalls. They glimmer in the distance like jewels. And suddenly the clumps stop. The road is empty for miles. There’s just me and the asphalt river cutting through a defile of half-naked trees, their leaves crinkled and clinging desperately to their dark branches. There’s the road and the naked sky and the tall, brown grass and me.

These empty stretches are the worst. Cars provide cover. And shelter. I sleep in the undamaged ones (I haven’t found a locked one yet). If you can call it sleep. Stale, stuffy air; you can’t crack the windows, and leaving the door open is out of the question. The gnaw of hunger. And the night thoughts. Alone, alone, alone.

And the baddest of the bad night thoughts:

I’m no alien drone designer, but if I were going to make one, I’d make sure that its detection device was sensitive enough to pick up a body’s heat signature through a car roof. It never failed: The moment I started to drift off, I imagined all four doors flying open and dozens of hands reaching for me, hands attached to arms attached to whatever they are. And then I’m up, fumbling with my M16, peeking over the backseat, then doing a 360, feeling trapped and more than a little blind behind the fogged-up windows.

Dawn comes. I wait for the morning fog to burn off, then sip some water, brush my teeth, double-check my weapons, inventory my supplies, and hit the road again. Look up, look down, look all around. Don’t pause at the exits. Water’s fine for now. No way am I going anywhere near a town unless I have to.

For a lot of reasons.

You know how you can tell when you’re getting close to one? The smell. You can smell a town from miles away.

It smells like smoke. And raw sewage. And death.

In the city it’s hard to take two steps without stumbling over a corpse. Funny thing: People die in clumps, too.

I begin to smell Cincinnati about a mile before spotting the exit sign. A thick column of smoke rises lazily toward the cloudless sky.

Cincinnati is burning.

I’m not surprised. After the 3rd Wave, the second most common thing you found in cities, after the bodies, were fires. A single lightning strike could take out ten city blocks. There was no one left to put the fires out.

My eyes start to water. The stench of Cincinnati makes me gag. I stop long enough to tie a rag around my mouth and nose and then quicken my pace. I pull the rifle off my shoulder and cradle it as I quickstep. I have a bad feeling about Cincinnati. The old voice inside my head is awake.

Hurry, Cassie. Hurry.

And then, somewhere between Exits 17 and 18, I find the bodies.