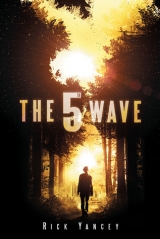

Текст книги "The 5th Wave"

Автор книги: Rick Yancey

Жанры:

Подростковая литература

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 27 страниц)

HE LEAVES THE OLD FARMHOUSE every night to patrol the grounds and to hunt. He tells me he has plenty of dry goods and his mom was a devoted preserver and canner, but he likes fresh meat. So he leaves me to find edible creatures to kill, and on the fourth day he comes into the room with an honest-to-God hamburger on a hot, homemade bun and a side of roasted potatoes. It’s the first real food I’ve had since escaping Camp Ashpit. It’s also a freaking hamburger, which I haven’t tasted since the Arrival and which, I think I’ve pointed out, I was willing to kill for.

“Where’d you get the bread?” I ask midway through the burger, grease rolling down my chin. I haven’t had bread, either. It’s light and fluffy and slightly sweet.

He could give me any number of snarky replies, since there is only one way he could have gotten it. He doesn’t. “I baked it.”

After feeding me, he changes the dressing on my leg. I ask if I want to look. He says no, I most definitely do not want to look. I want to get out of bed, take a real bath, be like a person again. He says it’s too soon. I tell him I want to wash and comb out my hair. Too soon, he insists. I tell him if he won’t help me I’m going to smash the kerosene lamp over his head. So he sets a kitchen chair in the middle of the claw-foot tub in the little bathroom down the hall with its peeling flowery wallpaper and carries me to it, plops me down, leaves, and comes back with a big metal tub filled with steaming water.

The tub must be very heavy. His biceps strain against his sleeves, like he’s Bruce Banner mid-Hulkifying, and the veins stand out on his neck. The water smells faintly of rose petals. He uses a lemonade pitcher decorated with smiley-faced suns as a ladle, and I lean my head back for him. He starts to work in the shampoo, and I push his hands away. This part I can do myself.

The water courses from my hair into the gown, plastering the cotton to my body. Evan clears his throat, and when he turns his head his thick hair does this swooshy thing across his dark brow and I’m a little disturbed, but in a pleasant way. I ask for the widest-toothed comb he has, and he digs in the cupboard beneath the sink while I watch him out of the corner of my eye, barely noticing the way his powerful shoulders roll beneath his flannel shirt, or his faded jeans with the frayed back pockets, definitely paying no attention to the roundness of his butt inside those jeans, totally ignoring the way my earlobes burn like fire beneath the lukewarm water dripping from my hair. After a couple eternities, he finds a comb, asks if I need anything before he leaves, and I mumble no when what I really want to do is laugh and cry at the same time.

Alone, I force myself to concentrate on my hair, which is a horrible mess. Knots and tangles and bits of leaf and little wads of dirt. I work on the knots until the water goes cold and I start to shiver in my wet nightie. I pause once in the chore when I hear a tiny sound just outside the door.

“Are you standing out there?” I ask. The small, tiled bathroom magnifies sound like an echo chamber.

There’s a pause, and then a soft answer: “Yes.”

“Why are you standing out there?”

“I’m waiting to rinse your hair.”

“This is going to take a while,” I say.

“That’s okay.”

“Why don’t you go bake a pie or something and come back in about fifteen minutes.”

I don’t hear an answer. But I don’t hear him leave.

“Are you still there?”

The floorboards in the hall creak. “Yes.”

I give up after another ten minutes of teasing and pulling. Evan comes back in, sits on the edge of the tub. I rest my head in the palm of his hand while he rinses the suds from my hair.

“I’m surprised you’re here,” I tell him.

“I live here.”

“That you stayed here.” A lot of young guys left for the nearest police station, National Guard armory, or military base after news of the 2nd Wave started trickling in from survivors fleeing inland. Like after 9/11, only times ten.

“There were eight of us, counting Mom and Dad,” he says. “I’m the oldest. After they died, I took care of the kids.”

“Slower, Evan,” I say as he empties half the pitcher onto my head. “I feel like I’m being waterboarded.”

“Sorry.” He presses the edge of his hand against my forehead to act as a dam. The water is deliciously warm and tickly. I close my eyes.

“Did you get sick?” I ask.

“Yeah. Then I got better.” He ladles more water from the metal tub into the pitcher, and I hold my breath, anticipating the tickly warmth. “My youngest sister, Val, she died two months ago. That’s her bedroom you’re in. Since then I’ve been trying to figure out what to do. I know I can’t stay here forever, but I’ve hiked all the way to Cincinnati, and maybe I don’t need to explain why I’m never going back.”

One hand pours while the other presses the wet hair against my scalp to wring out the excess water. Firmly, not too hard, just right. Like I’m not the first girl whose hair he’s washed. A little, hysterical voice inside my head is screaming, What do you think you’re doing? You don’t even know this guy! but that same voice is going, Great hands; ask him for a scalp massage while he’s at it.

While outside my head, his deep, calm voice is saying, “Now I’m thinking it doesn’t make sense to leave until it gets warmer. Maybe Wright-Patterson or Kentucky. Fort Knox is only a hundred and forty miles from here.”

“Fort Knox? What, you’re going on a heist?”

“It’s a fort, as in heavily fortified. A logical rallying point.” Gathering the ends of my hair in his fist and squeezing, and the plop-plops of the water spattering in the claw-foot tub.

“If it were me, I wouldn’t go anyplace that’s a logical rallying point,” I say. “Logically those’ll be the first points they wipe off the map.”

“From what you’ve told me about the Silencers, it’s not logical to rally anywhere.”

“Or stay anywhere longer than a few days. Keep your numbers small and keep moving.”

“Until…?”

“There is no until,” I snap at him. “There’s just unless.”

He dries my hair with a fluffy white towel. There’s a fresh nightie lying on the closed toilet seat. I look up into those chocolate-colored eyes and say, “Turn around.” He turns around. I reach past the frayed back pockets of the jeans that conform to the butt that I’m not looking at and pick up the dry nightie. “If you try to peek in that mirror, I’ll know,” I warn the guy who’s already seen me naked, but that was unconsciously naked, which is not the same thing. He nods, lowers his head, and pinches his lower lip like he’s sealing off a smile.

I wiggle out of the wet nightie, slip the dry one over my head, and tell him it’s okay to turn around.

He lifts me from the chair and carries me back to his dead sister’s bed, and I have one arm around his shoulders, and his arm is tight—though not too tight—across my waist. His body feels about twenty degrees warmer than mine. He eases me onto the mattress and pulls the quilts over my bare legs. His cheeks are very smooth, his hair neatly groomed, and his cuticles, as I’ve pointed out, are impeccable. Which means grooming is very high on his list of priorities in the postapocalyptic era. Why? Who’s around to see him?

“So how long has it been since you’ve seen another person?” I ask. “Besides me.”

“I see people practically every day,” he says. “The last living one before you was Val. Before her, it was Lauren.”

“Lauren?”

“My girlfriend.” He looks away. “She’s dead, too.”

I don’t know what to say. So I say, “The plague sucks.”

“It wasn’t the plague,” he says. “Well, she had it, but it wasn’t the plague that killed her. She did that herself, before it could.”

He’s standing awkwardly beside the bed. Doesn’t want to leave, doesn’t have an excuse to stay.

“I just couldn’t help but notice how nice…” No, not a good intro. “I guess it’s hard, when it’s just you, to really care about…” Nuh-uh.

“Care about what?” he asks. “One person when almost every person is gone?”

“I wasn’t talking about me.” And then I give up trying to come up with a polite way to say it. “You take a lot of pride in how you look.”

“It isn’t pride.”

“I wasn’t accusing you of being stuck-up—”

“I know; you’re thinking what’s the point now?”

Well, actually, I was hoping the point was me. But I don’t say anything.

“I’m not sure,” he says. “But it’s something I can control. It gives structure to my day. It makes me feel more…” He shrugs. “More human, I guess.”

“And you need help with that? Feeling human?”

He looks at me funny, then gives me something to think about for a long time after he leaves:

“Don’t you?”

HE’S GONE MOST of the nights. During the days he waits on me hand and foot, so I don’t know when the guy sleeps. By the second week, I was about to go nuts cooped up in the little upstairs bedroom, and on a day when the temperature climbed above freezing, he helped me into some of Val’s clothes, averting his eyes at the appropriate moments, and carried me downstairs to sit on the front porch, throwing a big wool blanket over my lap. He left me there and came back with two steaming mugs of hot chocolate. I can’t say much about the view. Brown, lifeless, undulating earth, bare trees, a gray, featureless sky. But the cold air felt good against my cheeks, and the hot chocolate was the perfect temperature.

We don’t talk about the Others. We talk about our lives before the Others. He was going to study engineering at Kent State after graduating. He had offered to stay on the farm for a couple years, but his father insisted that he go to college. He had known Lauren since the fourth grade, started dating her in their sophomore year. There was talk of marriage. He noticed I got quiet when Lauren came up. Like I said, Evan is a noticer.

“How about you?” he asked. “Did you have a boyfriend?”

“No. Well, kind of. His name was Ben Parish. I guess you could say he had this thing for me. We dated a couple of times. You know, casually.”

I wonder what made me lie to him. He doesn’t know Ben Parish from a hole in the ground. Which is kind of the same way Ben knew me. I swirled the remains of my hot chocolate and avoided his eyes.

The next morning he showed up at my bedside with a crutch carved from a single piece of wood. Sanded to a glossy finish, lightweight, the perfect height. I took one look at it and demanded that he name three things he isn’t good at.

“Roller skating, singing, and talking to girls.”

“You left out stalking,” I told him as he helped me out of the bed. “I can always tell when you’re lurking around corners.”

“You only asked for three.”

I’m not going to lie: My rehab sucked. Every time I put weight on my leg, pain shot up the left side of my body, my knee buckled, and the only things that kept me from falling flat on my ass were Evan’s strong arms.

But I kept at it during that long day and the long days that followed. I was determined to get strong. Stronger than before the Silencer cut me down and abandoned me to die. Stronger than I was in my little hideout in the woods, rolled up in my sleeping bag, feeling sorry for myself while Sammy was suffering God knows what. Stronger than the days at Camp Ashpit, where I walked around with a huge chip on my shoulder, angry at the world for being what the world was, for what it had always been: a dangerous place that our human noise had made seem a whole lot safer.

Three hours of rehab in the morning. Thirty-minute break for lunch. Then three more hours of rehab in the afternoon. Working on rebuilding my muscles until I felt them melt into a sweaty, jellylike mass.

But I still wasn’t done for the day. I asked Evan what happened to my Luger. I had to get over my fear of guns. And my accuracy sucked. He showed me the proper grip, how to use the sight. He set up empty gallon-size paint cans on the fence posts for targets, replacing those with smaller cans as my aim improved. I ask him to take me hunting with him—I need to get used to hitting a moving, breathing target—but he refuses. I’m still pretty weak, I can’t even run yet, and what happens if a Silencer spots us?

We take walks at sunset. At first I didn’t make it more than half a mile before my leg gave out and Evan had to carry me back to the farmhouse. But each day I was able to go a hundred yards farther than the day before. A half mile became three-quarters became a whole. By the second week I was doing two miles without stopping. Can’t run yet, but my pace and stamina have vastly improved.

Evan stays with me through dinner and a couple hours into the night, and then he shoulders his rifle and tells me he’ll be back before sunrise. I’m usually asleep when he comes in—and it’s usually way past sunrise.

“Where do you go every night?” I asked him one day.

“Hunting.” A man of few words, this Evan Walker.

“You must be a lousy hunter,” I teased him. “You hardly ever come back with anything.”

“I’m actually very good,” he said matter-of-factly. Even when he says something that, on paper, sounds like bragging, it isn’t. It’s the way he says it, casually, like he’s talking about the weather.

“You just don’t have the heart to kill?”

“I have the heart to do what I have to do.” He ran his fingers through his hair and sighed. “In the beginning it was about staying alive. Then it was about protecting my brothers and sisters from the crazies running around after the plague first hit. Then it was about protecting my territory and supplies…”

“What’s it about now?” I asked quietly. That was the first time I’d seen him even mildly worked up.

“It settles my nerves,” he admitted with an embarrassed shrug. “Gives me something to do.”

“Like personal hygiene.”

“And I have trouble sleeping at night,” he went on. Wouldn’t look at me. Not looking at anything, really. “Well. Sleeping period. So after a while I gave up trying and started sleeping during the day. Or trying to. The fact is I only sleep two or three hours a day.”

“You must be really tired.”

He finally looked at me, and there was something sad and desperate in his eyes.

“That’s the worst part,” he said softly. “I’m not. I’m not tired at all.”

I was still uneasy about his disappearing at night, so once I tried to follow him. Bad idea. I lost him after ten minutes, got worried I’d get lost, turned to go back, and found myself staring up into his face.

He didn’t get mad. Didn’t accuse me of not trusting him. He just said, “You shouldn’t be out here, Cassie,” and escorted me inside.

More out of concern for my mental health than our personal safety (I don’t think he was completely sold on the whole Silencer idea), he hung heavy blankets over the windows in the great room downstairs so we could have a fire and light a couple of lamps. I waited there until he returned from his forays in the dark, sleeping on the big leather sofa or reading one of his mom’s battered paperback romance novels with the buffed-out, half-naked guys on the covers and the ladies dressed in full-length ball gowns caught in midswoon. Then around three in the morning he would come home, and we’d throw some more wood on the fire and talk. He doesn’t like to talk about his family much (when I asked about his mother’s taste in books, he just shrugged and said she liked literature). He steers the conversation back to me when things start getting too personal. Mostly he wants to talk about Sammy, as in how I plan to keep my promise to him. Since I have no idea how I’m going to do that, the discussion never ends well. I’m vague; he presses for specifics. I’m defensive; he’s insistent. Finally I get mean, and he shuts down.

“So walk me through this again,” he says late one night after going around and around for an hour. “You don’t know exactly who or what they are, but you know they have lots of heavy artillery and access to alien weaponry. You don’t know where they’ve taken your brother, but you’re going there to rescue him. Once you get there, you don’t know how you’re going to rescue him, but—”

“What is this?” I ask. “Are you trying to help or make me feel stupid?”

We’re sitting on the big fluffy rug in front of the fireplace, his rifle on one side, my Luger on the other, and the two of us in between.

He holds up his hands in a fake gesture of surrender. “I’m just trying to understand.”

“I’m starting at Camp Ashpit and picking up the trail from there,” I say for about the thousandth time. I think I know why he keeps asking the same questions, but he’s so damned obtuse, it’s hard to pin him down. Of course, he could say the same thing about me. As plans go, mine is more of a general goal pretending to be a plan.

“And if you can’t pick up the trail?” he asks.

“I won’t give up until I do.”

He’s nodding a nod that says, I’m nodding, but I’m not nodding because I think what you’re saying makes sense. I’m nodding because I think you’re a total fool and I don’t want you to go all kung fu on me with a crutch I made with my own hands.

So I say, “I’m not a total fool. You’d do the same for Val.”

He doesn’t have a quick reply to that. He wraps his arms around his legs and rests his chin on his knees, staring at the fire.

“You think I’m wasting my time,” I accuse his flawless profile. “You think Sammy’s dead.”

“How could I know that, Cassie?”

“I’m not saying you know that. I’m saying you think that.”

“Does it matter what I think?”

“No, so shut up.”

“I wasn’t saying anything. You said—”

“Don’t…say…anything.”

“I’m not.”

“You just did.”

“I’ll stop.”

“But you’re not. You say you will, then you just keep going.”

He starts to say something, then shuts his mouth so hard, I hear his teeth click.

“I’m hungry,” I say.

“I’ll get you something.”

“Did I ask you to get me anything?” I want to pop him right in that perfectly shaped mouth. Why do I want to hit him? Why am I so mad right now? “I’m perfectly capable of waiting on myself. This is the problem, Evan. I didn’t show up here to give your life purpose now that your life’s over. That’s up to you to figure out.”

“I want to help you,” he says, and for the first time I see real anger in those puppy-dog eyes. “Why can’t saving Sammy be my purpose, too?”

His question follows me into the kitchen. It hangs over my head like a cloud while I slap some cured deer meat onto some flat bread Evan must have baked in his outdoor oven like the Eagle Scout he is. It follows me as I hobble back into the great room and plop down on the sofa directly behind his head. I have this urge to kick him right between his broad shoulders. On the table beside me is a book entitled Love’s Desperate Desire. Based on the cover, I would have called it My Spectacular Washboard Abs.

That’s my big problem. That’s it! Before the Arrival, guys like Evan Walker never looked twice at me, much less shot wild game for me and washed my hair. They never grabbed me by the back of the neck like the airbrushed model on his mother’s paperback, abs a-clenching, pecs a-popping. My eyes have never been looked deeply into, or my chin raised to bring my lips within an inch of theirs. I was the girl in the background, the just-friend, or—worse—the friend of a just-friend, the you-sit-next-to-her-in-geometry-but-can’t-remember-her-name girl. It would have been better if some middle-aged collector of Star Wars action figures had found me in that snowbank.

“What?” I ask the back of his head. “Now you’re giving me the silent treatment?”

His shoulders jiggle up and down. You know, one of those wry, silent chuckles, accompanied by a rueful shake of the head. Girls! So silly.

“I should have asked, I guess,” he says. “I shouldn’t have assumed.”

“What?”

He rotates around on his butt to face me. Me on the sofa, him on the floor, looking up. “That I was going with you.”

“What? We weren’t even talking about that! And why would you want to go with me, Evan? Since you think he’s dead?”

“I just don’t want you to be dead, Cassie.”

That does it.

I hurl my deer meat at his head. The plate glances off his cheek, and he’s up and in my face before I can blink. He leans in close, putting his hands on either side of me, boxing me in with his arms. Tears shine in his eyes.

“You’re not the only one,” he says through gritted teeth. “My twelve-year-old sister died in my arms. She choked to death on her own blood. And there was nothing I could do. It makes me sick, the way you act as if the worst disaster in human history somehow revolves around you. You’re not the only one who’s lost everything—not the only one who thinks they’ve found the one thing that makes any of this shit make sense. You have your promise to Sammy, and I have you.”

He stops. He’s gone too far, and he knows it.

“You don’t ‘have’ me, Evan,” I say.

“You know what I mean.” He’s looking intently at me, and it’s very hard to keep from turning away. “I can’t stop you from going. Well, I guess I could, but I also can’t let you go alone.”

“Alone is better. You know that. It’s the reason you’re still alive!” I poke my finger into his heaving chest.

He pulls away, and I fight the instinct to reach for him. There’s a part of me that doesn’t want him to pull away.

“But it’s not the reason you are,” he snaps. “You won’t last two minutes out there without me.”

I explode. I can’t help it. It was the perfectly wrong thing to say at the perfectly wrong time.

“Screw you!” I shout. “I don’t need you. I don’t need anyone! Well, I guess if I needed someone to wash my hair or slap a bandage on a boo-boo or bake me a cake, you’d be the guy!”

After two tries, I manage to get on my feet. Time for the angrily-storming-out-of-the-room part of the argument, while the guy folds his arms over his manly chest and pouts. I pause halfway up the stairs, telling myself I’m stopping to catch my breath, not to let him catch up. He’s not following me anyway. So I struggle up the remaining steps and into my bedroom.

No, not my bedroom. Val’s bedroom. I don’t have a bedroom anymore. Probably never will again.

Oh, screw self-pity. The world doesn’t revolve around you. And screw guilt. You aren’t the one who made Sammy get on that bus. And while you’re at it, screw grief. Evan’s crying over his baby sister won’t bring her back.

I have you. Well, Evan, the truth is it doesn’t matter whether there are two of us or two hundred of us. We don’t stand a chance. Not against an enemy like the Others. I’m making myself strong for…what? So when I go down, at least I go down strong? What difference does that make?

I slap Bear from his perch on the bed with an angry snarl. What the hell are you staring at? He flops over to his side, arm sticking up in the air like he’s raising his hand in class to ask a question.

Behind me, the door creaks on its rusty hinges.

“Get out,” I say without turning around.

Another creeeeak. Then a click. Then silence.

“Evan, are you standing outside that door?”

Pause. “Yes.”

“You’re kind of a lurker, you know that?”

If he answers, I don’t hear him. I’m hugging myself. Rubbing my hands up and down my arms. The little room is freezing. My knee aches like hell, but I bite my lip and remain stubbornly on my feet, my back to the door.

“Are you still there?” I say when I can’t take the silence anymore.

“If you leave without me, I’ll just follow you. You can’t stop me, Cassie. How are you going to stop me?”

I shrug helplessly, fighting back tears. “Shoot you, I guess.”

“Like you shot the Crucifix Soldier?”

The words hit me like a bullet between the shoulder blades. I whirl around and fling open the door. He flinches, but stands his ground.

“How do you know about him?” Of course, there’s only one way he could know. “You read my diary.”

“I didn’t think you were going to live.”

“Sorry to disappoint you.”

“I guess I wanted to know what happened—”

“You’re lucky I left the gun downstairs or I would shoot you right now. Do you know how creepy that makes me feel, knowing you read that? How much did you read?”

He lowers his eyes. A warm red blush spreads across his cheeks.

“You read all of it, didn’t you?” I’m totally embarrassed. I feel violated and ashamed. It’s ten times worse than when I first woke up in Val’s bed and realized he had seen me naked. That was just my body. This was my soul.

I punch him in the stomach. There’s no give at all; it’s like I hit a slab of concrete.

“I can’t believe you,” I shout. “You sat there—just sat there—while I lied about Ben Parish. You knew the truth and you just sat there and let me lie!”

He jams his hands in his pockets, looking at the floor. Like a little boy busted for breaking his mother’s antique vase. “I didn’t think it mattered that much.”

“You didn’t think…?” I’m shaking my head. Who is this guy? All of a sudden I’ve got a bad case of the jitters. Something is seriously wrong here. Maybe it’s the fact that he lost his whole family and his girlfriend or fiancée or whatever she was and for months he’s been living alone pretending that doing really nothing is really doing something. Maybe he’s cocooned himself on this isolated patch of Ohio farmland as a way of dealing with all the shit the Others have ladled out, or maybe he’s just weird—weird before the Arrival and just as weird after—but whatever it is, something is seriously twisted about this Evan Walker. He’s too calm, too rational, too cool for it to be completely, well, cool.

“Why did you shoot him?” he asks quietly. “The soldier in the convenience store.”

“You know why,” I say. I’m about to burst into tears.

He’s nodding. “Because of Sammy.”

Now I’m really confused. “It had nothing to do with Sammy.”

He looks up at me. “Sammy took the soldier’s hand. Sammy got on that bus. Sammy trusted. And now, even though I saved you, you won’t let yourself trust me.”

He grabs my hand. Squeezes it hard. “I’m not the Crucifix Soldier, Cassie. And I’m not Vosch. I’m just like you. I’m scared and I’m angry and I’m confused and I don’t know what the hell I’m going to do, but I do know you can’t have it both ways. You can’t say you’re human in one breath and a cockroach in the next. You don’t believe you’re a cockroach. If you believed that, you wouldn’t have turned to face the sniper on the highway.”

“Oh my God,” I whisper. “It was just a metaphor.”

“You want to compare yourself to an insect, Cassie? If you’re an insect, then you’re a mayfly. Here for a day and then gone. That doesn’t have anything to do with the Others. It’s always been that way. We’re here, and then we’re gone, and it’s not about the time we’re here, but what we do with the time.”

“What you’re saying makes absolutely no sense, you know that?” I feel myself leaning toward him, all the fight draining out of me. I can’t decide if he’s holding me back or holding me up.

“You’re the mayfly,” he murmurs.

And then Evan Walker kisses me.

Holding my hand against his chest, his other hand sliding across my neck, his touch feathery soft, sending a shiver that travels down my spine into my legs, which are having a hard time keeping me upright. I can feel his heart slamming against my palm and I can smell his breath and feel the stubble on his upper lip, a sandpapery contrast to the softness of his lips, and Evan is looking at me and I’m looking back at him.

I pull back just enough to speak. “Don’t kiss me.”

He lifts me into his arms. I seem to float upward forever, like when I was a little girl and Daddy flung me into the air, feeling as if I’d just keep going up until I reached the edge of the galaxy.

He lays me on the bed. I say, right before he kisses me again, “If you kiss me again, I’m going to knee you in the balls.”

His hands are incredibly soft, like a cloud touching me.

“I won’t let you just…” He searches for the right word. “…fly away from me, Cassie Sullivan.”

He blows out the candle beside the bed.

I feel his kiss more intensely now, in the darkness of the room where his sister died. In the quiet of the house where his family died. In the stillness of the world where the life we knew before the Arrival died. He tastes my tears before I can feel them. Where there would be tears, his kiss.

“I didn’t save you,” he whispers, lips tickling my eyelashes. “You saved me.”

He repeats it over and over, until we fall asleep pressed against each other, his voice in my ear, my tears in his mouth.

“You saved me.”