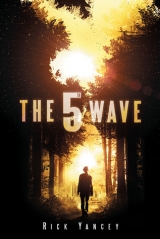

Текст книги "The 5th Wave"

Автор книги: Rick Yancey

Жанры:

Подростковая литература

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 27 страниц)

G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

An imprint of Penguin Young Readers Group.

Published by The Penguin Group.

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014, USA.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.).

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England.

Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd).

Penguin Group (Australia), 707 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3008, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd).

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Center, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi–110 017, India.

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd).

Penguin Books South Africa, Rosebank Office Park, 181 Jan Smuts Avenue,

Parktown North 2193, South Africa.

Penguin China, B7 Jiaming Center, 27 East Third Ring Road North,

Chaoyang District, Beijing 100020, China.

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England.

Copyright © 2013 by Rick Yancey.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission in writing from the publisher, G. P. Putnam’s Sons, an imprint of Penguin Young Readers Group, 345 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014.

G. P. Putnam’s Sons, Reg. U.S. Pat & Tm. Off. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Published simultaneously in Canada.

Cassiopeia photo copyright © iStockphoto.com/Manfred_Konrad.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Yancey, Richard. The 5th Wave / Rick Yancey. pages cm

Summary: “Cassie Sullivan, the survivor of an alien invasion, must rescue her young brother from the enemy with help from a boy who may be one of them”—Provided by publisher.

[1. Extraterrestrial beings—Fiction. 2. Survival—Fiction. 3. War—Fiction. 4. Science fiction.] I. Title. II. Title: Fifth Wave. PZ7.Y19197Aah 2013 [Fic]—dc23 2012047622

ISBN: 978-1-101-59896-2

For Sandy,

whose dreams inspire

and whose love endures

IF ALIENS EVER VISIT US, I think the outcome would be much as when Christopher Columbus first landed in America, which didn’t turn out very well for the Native Americans.

—Stephen Hawking

THE 1ST WAVE: Lights Out

THE 1ST WAVE: Lights Out

THE 2ND WAVE: Surf’s Up

THE 2ND WAVE: Surf’s Up

THE 3RD WAVE: Pestilence

THE 3RD WAVE: Pestilence

THE 4TH WAVE: Silencer

THE 4TH WAVE: Silencer

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Intrusion: 1995

I: The Last Historian

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

II: Wonderland

25

26

27

28

29

30

III: Silencer

31

IV: Mayfly

32

33

34

35

36

V: The Winnowing

37

38

39

40

41

VI: The Human Clay

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

VII: The Heart to Kill

53

54

55

VIII: The Spirit of Vengeance

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

IX: A Flower to the Rain

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

X: A Thousand Ways

78

79

XI: The Infinite Sea

80

XII: Because of Kistner

81

82

XIII: The Black Hole

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

Acknowledgments

The Monstrumologist

THERE WILL BE NO AWAKENING.

The sleeping woman will feel nothing the next morning, only a vague sense of unease and the unshakable feeling that someone is watching her. Her anxiety will fade in less than a day and will soon be forgotten.

The memory of the dream will linger a little longer.

In her dream, a large owl perches outside the window, staring at her through the glass with huge, white-rimmed eyes.

She will not awaken. Neither will her husband beside her. The shadow falling over them will not disturb their sleep. And what the shadow has come for—the baby within the sleeping woman—will feel nothing. The intrusion breaks no skin, violates not a single cell of her or the baby’s body.

It is over in less than a minute. The shadow withdraws.

Now it is only the man, the woman, the baby inside her, and the intruder inside the baby, sleeping.

The woman and man will awaken in the morning, the baby a few months later when he is born.

The intruder inside him will sleep on and not wake for several years, when the unease of the child’s mother and the memory of that dream have long since faded.

Five years later, at a visit to the zoo with her child, the woman will see an owl identical to the one in the dream. Seeing the owl is unsettling for reasons she cannot understand.

She is not the first to dream of owls in the dark.

She will not be the last.

ALIENS ARE STUPID.

I’m not talking about real aliens. The Others aren’t stupid. The Others are so far ahead of us, it’s like comparing the dumbest human to the smartest dog. No contest.

No, I’m talking about the aliens inside our own heads.

The ones we made up, the ones we’ve been making up since we realized those glittering lights in the sky were suns like ours and probably had planets like ours spinning around them. You know, the aliens we imagine, the kind of aliens we’d like to attack us, human aliens. You’ve seen them a million times. They swoop down from the sky in their flying saucers to level New York and Tokyo and London, or they march across the countryside in huge machines that look like mechanical spiders, ray guns blasting away, and always, always, humanity sets aside its differences and bands together to defeat the alien horde. David slays Goliath, and everybody (except Goliath) goes home happy.

What crap.

It’s like a cockroach working up a plan to defeat the shoe on its way down to crush it.

There’s no way to know for sure, but I bet the Others knew about the human aliens we’d imagined. And I bet they thought it was funny as hell. They must have laughed their asses off. If they have a sense of humor…or asses. They must have laughed the way we laugh when a dog does something totally cute and dorky. Oh, those cute, dorky humans! They think we think like they do! Isn’t that adorable?

Forget about flying saucers and little green men and giant mechanical spiders spitting out death rays. Forget about epic battles with tanks and fighter jets and the final victory of us scrappy, unbroken, intrepid humans over the bug-eyed swarm. That’s about as far from the truth as their dying planet was from our living one.

The truth is, once they found us, we were toast.

SOMETIMES I THINK I might be the last human on Earth.

Which means I’m the last human in the universe.

I know that’s dumb. They can’t have killed everyone…yet. I see how it could happen, though, eventually. And then I think that’s exactly what the Others want me to see.

Remember the dinosaurs? Well.

So I’m probably not the last human on Earth, but I’m one of the last. Totally alone—and likely to stay that way—until the 4th Wave rolls over me and carries me down.

That’s one of my night thoughts. You know, the three-in-the-morning, oh-my-God-I’m-screwed thoughts. When I curl into a little ball, so scared I can’t close my eyes, drowning in fear so intense I have to remind myself to breathe, will my heart to keep beating. When my brain checks out and begins to skip like a scratched CD. Alone, alone, alone, Cassie, you’re alone.

That’s my name. Cassie.

Not Cassie for Cassandra. Or Cassie for Cassidy. Cassie for Cassiopeia, the constellation, the queen tied to her chair in the northern sky, who was beautiful but vain, placed in the heavens by the sea god Poseidon as a punishment for her boasting. In Greek, her name means “she whose words excel.”

My parents didn’t know the first thing about that myth. They just thought the name was pretty.

Even when there were people around to call me anything, no one ever called me Cassiopeia. Just my father, and only when he was teasing me, and always in a very bad Italian accent: Cass-ee-oh-PEE-a. It drove me crazy. I didn’t think he was funny or cute, and it made me hate my own name. “I’m Cassie!” I’d holler at him. “Just Cassie!” Now I’d give anything to hear him say it just one more time.

When I was turning twelve—four years before the Arrival—my father gave me a telescope for my birthday. On a crisp, clear fall evening, he set it up in the backyard and showed me the constellation.

“See how it looks like a W?” he asked.

“Why did they name it Cassiopeia if it’s shaped like a W?” I replied. “W for what?”

“Well…I don’t know that it’s for anything,” he answered with a smile. Mom always told him it was his best feature, so he trotted it out a lot, especially after he started going bald. You know, to drag the other person’s eyes downward. “So, it’s for anything you like! How about wonderful? Or winsome? Or wise?” He dropped his hand on my shoulder as I squinted through the lens at the five stars burning over fifty light-years from the spot on which we stood. I could feel my father’s breath against my cheek, warm and moist in the cool, dry autumn air. His breath so close, the stars of Cassiopeia so very far away.

The stars seem a lot closer now. Closer than the three hundred trillion miles that separate us. Close enough to touch, for me to touch them, for them to touch me. They’re as close to me as his breath had been.

That sounds crazy. Am I crazy? Have I lost my mind? You can only call someone crazy if there’s someone else who’s normal. Like good and evil. If everything was good, then nothing would be good.

Whoa. That sounds, well…crazy.

Crazy: the new normal.

I guess I could call myself crazy, since there is one other person I can compare myself to: me. Not the me I am now, shivering in a tent deep in the woods, too afraid to even poke her head from the sleeping bag. Not this Cassie. No, I’m talking about the Cassie I was before the Arrival, before the Others parked their alien butts in high orbit. The twelve-year-old me, whose biggest problems were the spray of tiny freckles on her nose and the curly hair she couldn’t do anything with and the cute boy who saw her every day and had no clue she existed. The Cassie who was coming to terms with the painful fact that she was just okay. Okay in looks. Okay in school. Okay at sports like karate and soccer. Basically the only unique things about her were the weird name—Cassie for Cassiopeia, which nobody knew about, anyway—and her ability to touch her nose with the tip of her tongue, a skill that quickly lost its impressiveness by the time she hit middle school.

I’m probably crazy by that Cassie’s standards.

And she sure is crazy by mine. I scream at her sometimes, that twelve-year-old Cassie, moping over her hair or her weird name or at being just okay. “What are you doing?” I yell. “Don’t you know what’s coming?”

But that isn’t fair. The fact is she didn’t know, had no way of knowing, and that was her blessing and why I miss her so much, more than anyone, if I’m being honest. When I cry—when I let myself cry—that’s who I cry for. I don’t cry for myself. I cry for the Cassie that’s gone.

And I wonder what that Cassie would think of me.

The Cassie who kills.

HE COULDN’T HAVE BEEN much older than me. Eighteen. Maybe nineteen. But hell, he could have been seven hundred and nineteen for all I know. Five months into it and I’m still not sure if the 4th Wave is human or some kind of hybrid or even the Others themselves, though I don’t like to think that the Others look just like us and talk just like us and bleed just like us. I like to think of the Others as being…well, other.

I was on my weekly foray for water. There’s a stream not far from my campsite, but I’m worried it might be contaminated, either from chemicals or sewage or maybe a body or two upstream. Or poisoned. Depriving us of clean water would be an excellent way to wipe us out quickly.

So once a week I shoulder my trusty M16 and hike out of the forest to the interstate. Two miles south, just off Exit 175, there’re a couple of gas stations with convenience stores attached. I load up as much bottled water as I can carry, which isn’t a lot because water is heavy, and get back to the highway and the relative safety of the trees as quickly as I can, before night falls completely. Dusk is the best time to travel. I’ve never seen a drone at dusk. Three or four during the day and a lot more at night, but never at dusk.

From the moment I slipped through the gas station’s shattered front door, I knew something was different. I didn’t see anything different—the store looked exactly like it had a week earlier, the same graffiti-scrawled walls, overturned shelves, floor strewn with empty boxes and caked-in rat feces, the busted-open cash registers and looted beer coolers. It was the same disgusting, stinking mess I’d waded through every week for the past month to get to the storage area behind the refrigerated display cases. Why people grabbed the beer and soda, the cash from the registers and safe, the rolls of lottery tickets, but left the two pallets of drinking water was beyond me. What were they thinking? It’s an alien apocalypse! Quick, grab the beer!

The same disaster of spoilage, the same stench of rats and rotted food, the same fitful swirl of dust in the murky light pushing through the smudged windows, every out-of-place thing in its place, undisturbed.

Still.

Something was different.

I was standing in the little pool of broken glass just inside the doorway. I didn’t see it. I didn’t hear it. I didn’t smell or feel it. But I knew it.

Something was different.

It’s been a long time since humans were prey animals. A hundred thousand years or so. But buried deep in our genes the memory remains: the awareness of the gazelle, the instinct of the antelope. The wind whispers through the grass. A shadow flits between the trees. And up speaks the little voice that goes, Shhhh, it’s close now. Close.

I don’t remember swinging the M16 from my shoulder. One minute it was hanging behind my back, the next it was in my hands, muzzle down, safety off.

Close.

I’d never fired it at anything bigger than a rabbit, and that was a kind of experiment, to see if I could actually use the thing without blowing off one of my own body parts. Once I shot over the heads of a pack of feral dogs that had gotten a little too interested in my campsite. Another time nearly straight up, sighting the tiny, glowering speck of greenish light that was their mothership sliding silently across the backdrop of the Milky Way. Okay, I admit that was stupid. I might as well have erected a billboard with a big arrow pointing at my head and the words YOO-HOO, HERE I AM!

After the rabbit experiment—it blew that poor damn bunny apart, turning Peter into this unrecognizable mass of shredded guts and bone—I gave up the idea of using the rifle to hunt. I didn’t even do target practice. In the silence that had slammed down after the 4th Wave struck, the report of the rounds sounded louder than an atomic blast.

Still, I considered the M16 my bestest of besties. Always by my side, even at night, burrowed into my sleeping bag with me, faithful and true. In the 4th Wave, you can’t trust that people are still people. But you can trust that your gun is still your gun.

Shhh, Cassie. It’s close.

Close.

I should have bailed. That little voice had my back. That little voice is older than I am. It’s older than the oldest person who ever lived.

I should have listened to that voice.

Instead, I listened to the silence of the abandoned store, listened hard. Something was close. I took a tiny step away from the door, and the broken glass crunched ever so softly under my foot.

And then the Something made a noise, somewhere between a cough and a moan. It came from the back room, behind the coolers, where my water was.

That’s the moment when I didn’t need a little old voice to tell me what to do. It was obvious, a no-brainer. Run.

But I didn’t run.

The first rule of surviving the 4th Wave is don’t trust anyone. It doesn’t matter what they look like. The Others are very smart about that—okay, they’re smart about everything. It doesn’t matter if they look the right way and say the right things and act exactly like you expect them to act. Didn’t my father’s death prove that? Even if the stranger is a little old lady sweeter than your great-aunt Tilly, hugging a helpless kitten, you can’t know for certain—you can never know—that she isn’t one of them, and that there isn’t a loaded .45 behind that kitten.

It isn’t unthinkable. And the more you think about it, the more thinkable it becomes. Little old lady has to go.

That’s the hard part, the part that, if I thought about it too much, would make me crawl into my sleeping bag, zip myself up, and die of slow starvation. If you can’t trust anyone, then you can trust no one. Better to take the chance that Aunty Tilly is one of them than play the odds that you’ve stumbled across a fellow survivor.

That’s friggin’ diabolical.

It tears us apart. It makes us that much easier to hunt down and eradicate. The 4th Wave forces us into solitude, where there’s no strength in numbers, where we slowly go crazy from the isolation and fear and terrible anticipation of the inevitable.

So I didn’t run. I couldn’t. Whether it was one of them or an Aunt Tilly, I had to defend my turf. The only way to stay alive is to stay alone. That’s rule number two.

I followed the sobbing coughs or coughing sobs or whatever you want to call them till I reached the door that opened to the back room. Hardly breathing, on the balls of my feet.

The door was ajar, the space just wide enough for me to slip through sideways. A metal rack on the wall directly in front of me and, to the right, the long narrow hallway that ran the length of the coolers. There were no windows back here. The only light was the sickly orange of the dying day behind me, still bright enough to hurl my shadow onto the sticky floor. I crouched down; my shadow crouched with me.

I couldn’t see around the edge of the cooler into the hall. But I could hear whoever—or whatever—it was at the far end, coughing, moaning, and that gurgling sob.

Either hurt badly or acting hurt badly, I thought. Either needs help or it’s a trap.

This is what life on Earth has become since the Arrival. It’s an either/or world.

Either it’s one of them and it knows you’re here or it’s not one of them and he needs your help.

Either way, I had to get up and turn that corner.

So I got up.

And I turned the corner.

HE LAY SPRAWLED against the back wall twenty feet away, long legs spread out in front of him, clutching his stomach with one hand. He was wearing fatigues and black boots and he was covered in grime and shimmering with blood. There was blood everywhere. On the wall behind him. Pooling on the cold concrete beneath him. Coating his uniform. Matted in his hair. The blood glittered darkly, black as tar in the semidarkness.

In his other hand was a gun, and that gun was pointed at my head.

I mirrored him. His handgun to my rifle. Fingers flexing on the triggers: his, mine.

It didn’t prove anything, his pointing a gun at me. Maybe he really was a wounded soldier and thought I was one of them.

Or maybe not.

“Drop your weapon,” he sputtered at me.

Like hell.

“Drop your weapon!” he shouted, or tried to shout. The words came out all cracked and crumbly, beaten up by the blood rising from his gut. Blood dribbled over his bottom lip and hung quivering from his stubbly chin. His teeth shone with blood.

I shook my head. My back was to the light, and I prayed he couldn’t see how badly I was shaking or the fear in my eyes. This wasn’t some damn rabbit that was stupid enough to hop into my camp one sunny morning. This was a person. Or, if it wasn’t, it looked just like one.

The thing about killing is you don’t know if you can actually do it until you actually do it.

He said it a third time, not as loud as the second. It came out like a plea.

“Drop your weapon.”

The hand holding his gun twitched. The muzzle dipped toward the floor. Not much, but my eyes had adjusted to the light by this point, and I saw a speck of blood run down the barrel.

And then he dropped the gun.

It fell between his legs with a sharp cling. He brought up his empty hand and held it, palm outward, over his shoulder.

“Okay,” he said with a bloody half smile. “Your turn.”

I shook my head. “Other hand,” I said. I hoped my voice sounded stronger than I felt. My knees had begun to shake and my arms ached and my head was spinning. I was also fighting the urge to hurl. You don’t know if you can do it until you do it.

“I can’t,” he said.

“Other hand.”

“If I move this hand, I’m afraid my stomach will fall out.”

I adjusted the butt of the rifle against my shoulder. I was sweating, shaking, trying to think. Either/or, Cassie. What are you going to do, either/or?

“I’m dying,” he said matter-of-factly. From this distance, his eyes were just pinpricks of reflected light. “So you can either finish me off or help me. I know you’re human—”

“How do you know?” I asked quickly, before he could die on me. If he was a real soldier, he might know how to tell the difference. It would be an extremely useful bit of information.

“Because if you weren’t, you would have shot me already.” He smiled again, his cheeks dimpled, and that’s when it hit me how young he was. Only a couple years older than me.

“See?” he said softly. “That’s how you know, too.”

“How I know what?” My eyes were tearing up. His crumpled-up body wiggled in my vision like an image in a fun-house mirror. But I didn’t dare release my grip on the rifle to rub my eyes.

“That I’m human. If I wasn’t, I would have shot you.”

That made sense. Or did it make sense because I wanted it to make sense? Maybe he dropped the gun to get me to drop mine, and once I did, the second gun he was hiding under his fatigues would come out and the bullet would say hello to my brain.

This is what the Others have done to us. You can’t band together to fight without trust. And without trust, there was no hope.

How do you rid the Earth of humans? Rid the humans of their humanity.

“I have to see your other hand,” I said.

“I told you—”

“I have to see your other hand!” My voice cracked then. Couldn’t help it.

He lost it. “Then you’re just going to have to shoot me, bitch! Just shoot me and get it over with!”

His head fell back against the wall, his mouth came open, and a terrible howl of anguish tumbled out and bounced from wall to wall and floor to ceiling and pounded against my ears. I didn’t know if he was screaming from the pain or the realization that I wasn’t going to save him. He had given in to hope, and that will kill you. It kills you before you die. Long before you die.

“If I show you,” he gasped, rocking back and forth against the bloody concrete, “if I show you, will you help me?”

I didn’t answer. I didn’t answer because I didn’t have an answer. I was playing this one nanosecond at a time.

So he decided for me. He wasn’t going to let them win, that’s what I think now. He wasn’t going to stop hoping. If it killed him, at least he would die with a sliver of his humanity intact.

Grimacing, he slowly pulled out his left hand. Not much day left now, hardly any light at all, and what light there was seemed to be flowing away from its source, from him, past me and out the half-open door.

His hand was caked in half-dried blood. It looked like he was wearing a crimson glove.

The stunted light kissed his bloody hand and flicked along the length of something long and thin and metallic, and my finger yanked back on the trigger, and the rifle kicked against my shoulder hard, and the barrel bucked in my hand as I emptied the clip, and from a great distance I heard someone screaming, but it wasn’t him screaming, it was me screaming, me and everybody else who was left, if there was anybody left, all of us helpless, hopeless, stupid humans screaming, because we got it wrong, we got it all wrong, there was no alien swarm descending from the sky in their flying saucers or big metal walkers like something out of Star Wars or cute little wrinkly E.T.s who just wanted to pluck a couple of leaves, eat some Reese’s Pieces, and go home. That’s not how it ends.

That’s not how it ends at all.

It ends with us killing each other behind rows of empty beer coolers in the dying light of a late-summer day.

I went up to him before the last of the light was gone. Not to see if he was dead. I knew he was dead. I wanted to see what he was still holding in his bloody hand.

It was a crucifix.