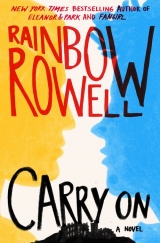

Текст книги "Carry On"

Автор книги: Rainbow Rowell

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

16

SIMON

Baz isn’t at breakfast the next morning. Or the next.

He isn’t in class.

The football team starts practising, and someone else takes his place.

After a week, the teachers stop saying his name when they take attendance.

I trail Niall and Dev for a few days, but they don’t seem to have Baz hidden away in a barn.…

I know I should be happy about Baz being gone—it’s what I’ve always said I wanted, to be free of him—but it seems so … wrong. People don’t just disappear like this.

Baz wouldn’t.

Baz is … indelible. He’s a human grease stain. (Mostly human.)

Three weeks into the term, I still find myself walking by the pitch, expecting to see him at football practice, and when I don’t, I take a hard turn out into the hills behind the school.

I hear Ebb shout at me before I see her. “Hiya, Simon—ahoy!”

She’s sitting above me a ways in the grass, with a goat curled up in her lap.

Ebb spends most of her time out in the hills when the weather is good. Sometimes she lets the goats roam the school grounds—she says they take care of weeds and predatory plants. The predatory plants at Watford will actually take you down if they get a chance; they’re magic. The goats aren’t, though. I asked Ebb once if the magic hurts the goats when they eat it. “They’re goats, Simon,” she said. “They can eat anything.”

When I get closer, I see that Ebb’s eyes are red. She wipes them with the sleeve of her jumper. It’s an old Watford school jumper, faded from red to pink and stained brown around the neck and wrists.

If it were anybody else, I’d worry. But Ebb is kind of a weeper. She’s like Eeyore if Eeyore hung out with goats all the time instead of letting Pooh and Piglet cheer him up.

It gets on Penelope’s nerves, all the crying, but I don’t mind. The thing about Ebb is, she never tells anybody else to keep their chin up or look on the bright side. It’s very comforting.

I flop down next to her in the grass and run my hand down the goat’s back.

“What’re you doing up here?” Ebb asks. “Shouldn’t you be at football practice?”

“I’m not on the team.”

She scratches the goat behind its ears. “Since when do ya let that stop you?”

“I…”

Ebb sniffs.

“Are you okay?” I ask.

“Ach. Sure.” She shakes her head, and her hair flies out around her ears. It’s dirty and blond and always cut in a sharp line above her jaw and across her forehead. “Just the time of year,” she says.

“Autumn?”

“Back to school. Reminds me of my own school days. You can’t go back, Simon, you can never go back.…” She rubs her nose on her cuff again, then rubs her cuff into the goat’s fur.

I don’t point out that Ebb’s never really left Watford. I don’t want to make fun of her—it seems like a pretty sweet deal to me. Spending your whole life here.

“Not everyone came back,” I say.

Her face falls. “Did we lose someone?”

Ebb’s brother died when they were young. It’s one of the reasons she’s so melancholy; she never got over it. I don’t want to set her off again.…

“No,” I say. “I mean—Baz. Basil didn’t come back.”

“Ah,” she says. “Young Master Pitch. Surely he’ll be back. His mother did so value education.”

“That’s what I said!”

“Well, you know him best,” she says.

“That’s what I said, too!”

Ebb nods and pets the goat. “To think you used to be at each other’s throats.”

“We’re still at each other’s throats.”

She looks up at me doubtfully. She has narrow blue eyes, bright blue—brighter somehow because her face is so dirty.

“Ebb,” I insist, “he tried to kill me.”

“Not successfully.” She shrugs. “Not recently.”

“He’s tried to kill me three times! That I know of! It doesn’t actually matter whether it worked.”

“It matters a bit,” she says. “’Sides, how old was he the first time, eleven? Twelve? That hardly counts.”

“It counts with me,” I say.

“Does it.”

I huff. “Yes. Ebb. It does. He hated me before he even met me.”

“Exactly,” she says.

“Exactly!”

“I’m just saying—been a long time since I had to spell you two apart.”

“Well, there’s no point in throwing down all the time,” I say. “Doesn’t get us anywhere. And it hurts. I suspect we’re saving up.”

“For what?” she asks.

“The end.”

“The end of school?”

“The end of the end,” I say. “The big fight.”

“So you were saving it, and then he didn’t come back for it?”

“Exactly!”

“Well, I wouldn’t lose hope,” Ebb says. “I think he’ll be back. His mother always valued a good education. I miss her this time a’year.…”

She wipes her eyes on her sleeve. I sigh. Sometimes, with Ebb, you’re better off just enjoying the silence. And the goats.

* * *

Three weeks pass. Four, five, six.

I stop looking for Baz anywhere where he’s supposed to be.

Whenever I hear someone on the stairs outside our room now, I know it’s Penny. I even let her spend the night sometimes and sleep in his bed; there doesn’t seem to be any immediate danger of Baz bursting in and lighting her on fire for it. (The Roommate’s Anathema doesn’t prevent you from hurting anyone else in your room.)

I hassle Niall a few more times, but he doesn’t even hint that he knows where Baz is. If anything, it seems like Niall’s hoping that I’ll turn up some answers.

I feel like I should talk to the Mage about it. About Baz. But I don’t want to talk to the Mage. I’m afraid he might still be planning to send me away.

Penny says it’s pointless to avoid him. “It’s not like you’ll fall off the Mage’s radar.”

But maybe I have.… And that bothers me, too.

The Mage is always gone a lot, but he’s hardly been at Watford at all this term. And whenever he is here, he’s surrounded by his Men.

Normally, he’d be checking on me. Calling me to his office. Giving me assignments, asking for help. Sometimes I think the Mage actually needs my help—he can trust me better than anyone—but sometimes I think he’s just testing me. To see what I’m made of. To keep me in order.

I’m sitting in class one day when I see the Mage walking alone towards the Weeping Tower. As soon as class ends, I make for the Tower.

It’s a tall, red brick building—one of the oldest at Watford, almost as old as the Chapel. It’s called the Weeping Tower because there are vines that grow in every summer and creep from the top down—and because the building has started to sag forward over the years, almost like it’s slumping in grief. Ebb says not to worry about it falling; the spells are still strong.

The dining hall is on the ground floor of the Tower, the whole ground floor, and then above that are classrooms and meeting rooms and summoning chambers; the Mage’s office and sanctum are at the very top.

He comes and goes as he needs to. The Mage has the whole magickal world to keep track of—in the UK, anyway—and hunting the Humdrum takes up a lot of his time.

The Humdrum doesn’t just attack me. That isn’t even the worst of it. (If it were, the other magicians probably would have thrown me to him by now.)

When the Humdrum first showed up, almost twenty years ago, holes began appearing in the magickal atmosphere. It seems like he (it?) can suck the magic out of a place, probably to use against us.

If you go to one of these dead spots, it’s like stepping into a room without air. There’s just nothing there for you, no magic—even I run dry.

Most magicians can’t take it. They’re so used to magic, to feeling magic, that they go spare without it. That’s how the monster got its name. One of the first magicians to encounter the holes said they were like an “insidious humdrum, a mundanity that creeps into your very soul.”

The dead spots stay dead. You get your magic back if you leave, but the magic never comes back to that place.

Magicians have had to leave their homes because the Humdrum has pulled the magic out from underneath them.

It’d be a disaster if the Humdrum ever came to Watford.

So far, he usually sends someone else—or something else, some dark creature—in after me.

It’s easy for the Humdrum to find allies. Every dark creature in this world and its neighbours would love to see the mages fall. The vampires, the werewolves, the demons and banshees, the Manticorps, the goblins—they all resent us. We can control magic, and they can’t. Plus we keep them in check. If the dark things had their way, the Normal world would be chaos. They’d treat regular people like livestock. We—magicians—need the Normals to live their normal lives, relatively unaffected by magic. Our spells depend on them being able to speak freely.

That explains why the dark creatures hate us.

But I still don’t know why the Humdrum has targeted me, specifically. Because I’m the most powerful magician, I suppose. Because I’m the biggest threat.

The Mage says that he himself followed my power like a beacon when it was time to bring me to Watford.

Maybe that’s how the Humdrum finds me, too.

I take a winding staircase to the top of the Weeping Tower, where it opens up into a round foyer. The school seal is laid out in marble tile on the floor and polished till it looks wet. And the domed ceiling has a mural of Merlin himself calling magic up through his hands into the sky, his mouth open. He kind of looks like the guy who hosts QI.

There are two doors. The Mage’s office is behind the tall, arched door on the left. And his sanctum, his rooms, is behind the smaller door on the right.

I knock on his office door first—no one answers. I consider knocking on the door to his rooms, but that feels too intimate. Maybe I’ll just leave him a note.

I open the door to the Mage’s office—it’s warded, but the wards are set to welcome me—then I walk in slowly, just in case I’m disturbing him.…

It’s dark. The curtains are drawn. The walls are normally lined with books, but a bunch have been taken down, and they’re piled in stacks around the desk.

I don’t turn on the light. I wish I’d brought some paper or something—I don’t want to scrounge around the Mage’s desk. It’s not the sort of desk that has Post-it notes and a WHILE YOU WERE OUT pad.

I pick up a heavy fountain pen. There’re a few sheets of paper on his desk, lists of dates, and I turn one over and write:

Sir, I’d like to talk to you when you have a moment. About everything. About my roommate.

And then I add:

(T. Basilton Grimm-Pitch.)

And then I wish I hadn’t, because of course the Mage knows who my roommate is, and now it sort of looks like I’ve signed it. So then I do sign it:

Simon

“Simon,” someone says, and I startle, dropping the pen.

Miss Possibelf is standing in the doorway, but doesn’t step inside the office.

Miss Possibelf is our Magic Words teacher, and the dean of students. She’s my favourite teacher. She’s not exactly friendly, but I think she genuinely cares, and she seems more human sometimes than the Mage. (Even though she’s not exactly human, I don’t think.…) She’s much more likely to notice if you’re feeling sick or miserable, or if your thumb is hanging on by a thread.

“Miss Possibelf,” I say. “The Mage isn’t in.”

“I see that—do you have business here?”

“I thought he might be here. There were a few things I was going to talk to him about.”

“He was here this morning, but he’s left again.” Miss Possibelf is tall and broad, with a thick silver plait hanging down her back. She’s impossibly graceful, and impossibly eloquent, and if she’s talking to you directly, her voice kind of tickles your ears. “You could talk to me,” she says.

She still doesn’t come in—she must not have permission to cross the wards.

“Well,” I say. “It’s partly about Baz. Basil. He hasn’t come back to school.”

“I’ve noticed,” she says.

“Do you know if he’s coming back?”

She looks down at her wand, a walking stick, and moves the handle in a circle. “I’m not sure.”

“Have you talked to his parents?” I ask.

She looks up at me. “That’s confidential.”

I nod and kick the side of the Mage’s desk—then realize what I’m doing and take a step away from it, tangling my fingers into the front of my hair.

Miss Possibelf clears her throat prettily; even across the room, it sends a buzz up the back of my neck.

“I can tell you,” she says, “that it’s school policy to contact a student’s parents when a child doesn’t return for the term.…”

“So you have talked to the Pitches?”

She narrows her dark brown eyes. “What do you hope to learn, Simon?”

I drop my hand in frustration. “The truth. Is he gone? Is he sick? Has the war started?”

“The truth…”

I keep waiting for her to blink. Even magicians blink.

“The truth,” she says, “is that I don’t have answers to any of those questions. His parents have been contacted. They were aware that he wasn’t in school, but they didn’t elaborate. Mr. Pitch is of legal age—like you, technically an adult. If he doesn’t attend this school, I’m not responsible for his welfare.”

“But you can’t just ignore it when a student doesn’t come back to school! What if he’s planning something?”

“Then that’s a concern for the Coven, not for the dean of students.”

“If Baz is off organizing an insurgency,” I press, “that’s all of our concern.”

She watches me. I push my jaw forward and stand my ground. (This is my standard move when I don’t know what else to do.) (Because if there’s one thing I’m good at…)

Miss Possibelf closes her eyes, but still not like she needs to blink—it’s more like she’s giving in. Good.

She looks back up at me. “Simon, I care about you, and I’ve always been honest with you. Listen to me—I don’t know where Basilton is. Maybe he is off planning something awful; I hope not, for his sake and yours. All I do know is that when I talked to his father, he seemed unsurprised and ill at ease; he knew that his son wasn’t here, and he didn’t seem happy. Honestly, Simon? He sounded like a man at the end of his rope.”

I puff a breath out hard through my nose and nod my head.

“That’s all I know,” she says. “I’ll tell you if I learn more, if I’m able.”

I nod again.

“Now, perhaps you should go to lunch.”

“Thank you, Miss Possibelf.”

As I move past her in the doorway, she tries to pat my arm—but I keep walking, and it’s awkward. I hear the heavy oak door close behind us.

I don’t go to lunch. I go for a walk that turns into a run that turns into me hacking away at a tree on the edge of the woods.

I can’t believe that my blade comes when I call for it.

17

SIMON

I stop looking for Baz anywhere where he’s supposed to be.…

But I don’t stop looking for him.

I take walks in the Wavering Wood at night. Penny sees the look on my face and doesn’t try to join me. Agatha’s always off doing schoolwork; she must be buckling down this year—maybe her dad’s promised her a new horse or something.

I used to love the Wood, I used to find it calming.

I realize after a few nights that I’m not just walking aimlessly; I’m covering the Wood like I’m sweeping it. Like we swept it that year that Elspeth disappeared—all of us holding hands, walking side by side, marking off parcels as we moved through them. I’m marking off parcels in my head now, casting for light and waving my blade back and forth to clear branches. I’ll mow the whole fucking forest down if I go on like this.

I don’t find anything. And I frighten the sprites. And a dryad comes out to tell me that I’m basically a one-man walking woodland apocalypse.

“What do you seek?” the nymph asks, hovering over the ground even though I’ve already told her that it gives me the creeps. She’s got hair like moss, and she’s dressed like one of those manga girls with the Victorian boots and the umbrellas.

“Baz,” I say. “My roommate.”

“The dead one? With the pretty eyes?”

“Yes.” Is Baz dead? I’ve never thought of him that way. I mean, he is a vampire, I guess. “Wait, are you saying he’s dead? Like, really dead?”

“All the bloodeaters are dead.”

“Have you actually seen him eat blood?”

She stares at me. My sword is stuck in the ground beside my feet.

“What do you seek, Chosen One?” She sounds irritated now. She lets her green brolly rest on her shoulder.

“My roommate. Baz. The bloodeater.”

“He’s not here,” she says.

“Are you sure?”

“More sure than you.”

I sigh and dig my sword deeper into the ground. “Well, I’m not sure at all.”

“You’re burning up goodwill here, magician.”

“How many times do I have to save the Wood to win you people over?”

“There’s no use saving it if you’re just going to hack it down.”

“I’m looking. For my roommate.”

“Your enemy,” she counters. She has grey-brown skin, ridged and rippled like bark, and her eyes glow like those mushrooms that grow deep in the woods.

“It doesn’t matter what he is,” I say, “you know who I’m talking about—how can you be sure he isn’t here?”

The dryad tilts her head back, like she’s listening to the trees behind her. Her every move sounds like a breeze blowing through branches.

“He isn’t here,” she says. “Unless he’s hiding.”

“Well, of course he’s hiding! He’s hiding bloody somewhere.”

“If we can’t see him here, magician, neither will you.”

I pick up my sword and sheathe it at my hip. “But you’ll tell me if you hear anything?”

“Probably not.”

“You’re impossible.”

“I’m improbable.”

“This is important,” I say. “A very dangerous person is missing.”

“Not dangerous to me,” she hisses. “Not dangerous to my sisters. We don’t bleed. We don’t play petty games of more and most.”

“Perhaps you’ve forgotten that Pitch is the House of Fire.” I gesture to the woods behind her, all of it flammable.

Her head snaps up. Her smile creaks down. She switches her umbrella to her other shoulder. “Fine.”

“Fine?”

“If we see your handsome bloodeater, we’ll tell him you’re looking for him.”

“Not. Helping.”

“We’ll tell the golden one, then.”

“The golden one … Am I the golden one?”

She scrunches her nose and shakes her mossy hair. Flowers bloom in it.

“Who, then?”

“Your golden one. His golden one. Your pistil and stigma.”

“Pistol … Do you mean Agatha?”

“Sister golden hair.”

“You’ll tell Agatha if you see Baz?”

“Yes.” Her umbrella twirls. “We find her peaceful.”

I sigh and rub the back of my hand into my forehead. “I’ve saved you at least three times. This whole forest. You know that, yeah?”

“What do you seek, Chosen One?”

“Nothing.” I throw my hands in the air and turn to leave, kicking at the nearest sapling. “Nothing!”

Nothing good ever happens in the Wavering Wood.

* * *

I walk the Wood.

I walk the fields.

I cover the school grounds between classes, poking through empty buildings, opening long-closed doors.

Sometimes Watford seems as big on the inside as the walled grounds and the outer lands combined.

There are secret rooms. Secret hallways. Entirely hidden wings that only reveal themselves if you know the right spell or have the right artefact.

There’s an extra storey between the second and third floors of the Cloisters. (Penny calls it “bonus content.”) It’s an echo of the floor above it. All the same things happen there, a day later.

There’s a moat below the moat.

And warrens in the hills.

There are three hidden gates, and I’ve only got one of them to open.

Sometimes it feels like I’ve spent my whole life looking for the map or key that would make Watford—the whole World of Mages—make sense.

But all I ever find are pieces of the puzzle. It’s like I’m in a dark room, and I only ever have enough light to see one corner of it at a time.

I spent most of my fifth year wandering the Catacombs below the White Chapel, searching for Baz. The Chapel’s at the centre of Watford; it’s the oldest building. No one knows whether Watford started as a school or something else. Maybe a magic abbey. Or a mages’ settlement—that’s what I’d like to believe. Imagine it, a walled town with magicians living together, practically out in the open. A magickal community.

The Catacombs sit beneath the Chapel and beyond it. There are probably lots of ways down, but I only know of one.

In our fifth year, I kept seeing Baz slip off towards the Chapel after dinner. I thought it must be some plot—a conspiracy.

I’d follow him to the Chapel, through the high, arched, never-locked front doors … Back behind the altar, behind the sanctuary and the Poets Corner … Through the secret door, and down into the Catacombs.

The Catacombs are properly creepy. Agatha would never go down there with me, and Penelope only went with me at first, when she still believed Baz might be up to something.

She stopped after a few months. She stopped going to Baz’s football matches with me, too. And stopped waiting with me in the hallway outside the balcony where Baz takes violin lessons.

But I couldn’t give it up. Not when all my clues were just starting to come together …

The blood on Baz’s cuffs. The fact that he could see in the dark. (He’d come back to our room at night and dress for bed without ever turning on the light.) Then I found a pile of dead rats in the Chapel basement, all pinched and used, like squeezed-up lemons.

I was alone when I finally confronted him. Deep in the Catacombs, inside the Children’s Tomb. Le Tombeau des Enfants. Baz was sitting in the corner, skulls stacked along the walls around him.

“You found me,” he said.

I already had my blade out. “I knew I would.”

“Now what?” He didn’t even stand. Just brushed some dust off his grey trousers and leaned back against the bones.

“Now you tell me what you’re up to,” I said.

He laughed at that. Baz was always laughing at me that year, but it came out flatter than usual. There were torches staining the grey room orange, but his skin was still chalky and white.

I adjusted my stance, spreading my feet below my hips, squaring my shoulders.

“They died in a plague,” he said.

“Who?”

Baz raised his hand—I flinched back.

He cocked an eyebrow and swept his arm in a flourish at the room around us. “Them,” he said. “Les enfants.” A lock of black hair fell over his forehead.

“Is that why you’re here? To track down a plague?”

Baz stared at me. He was 16, we both were, but he made me feel 5. He’s always made me feel like a child, like I’ll never catch up to him. Like he was born knowing everything about the World of Mages—it’s his world. It’s in his DNA.

“Yes, Snow,” he said. “I’m here to find a plague. I’m going to put it in a steaming beaker and infect all of Metropolis.”

I gripped my blade.

He looked bored.

“What are you doing down here?” I demanded, swinging the sword in the air.

“Sitting,” he said.

“No. None of that. I’ve finally caught you, after all these months—you’re going to tell me what you’re up to.”

“Most of the students died,” he said.

“Stop it. Stop distracting me.”

“They sent the well ones home. My great-great-uncle was the headmaster; he stayed to help nurse the sick and dying. His skull is down here, too. Maybe you could help me look for it—I’m told I share his aristocratic brow.”

“I’m not listening.”

“Magic didn’t help them,” Baz said.

I clenched my jaw.

“They didn’t have a spell for the plague yet,” he went on. “There weren’t any words that had enough power, the right kind of power.”

I stepped forward. “What are you doing here?”

He started singing to himself. “Ring around the rosie / a pocket full of posies…”

“Answer me, Baz.”

“Ashes, ashes…”

I swung my sword into the pile of bones beside him, sending skulls rattling and rolling.

He sneered and sat up, catching the skulls with his wand—“As you were!” They turned in the air and rolled back into place.

“Show some respect, Snow,” he said sharply, then slumped and leaned back again. “What do you want from me?”

“I want to know what you’re up to.”

“This is what I’m up to.”

“Sitting in a fucking tomb with a bunch of bones.”

“They’re not just bones. They’re students. And teachers. Everyone who dies at Watford is entombed down here.”

“So?”

“So?” he repeated.

I growled.

“Look, Snow…” He got to his feet. He was taller than me—he’s always been taller than me. Even after the summer when I grew three inches, I swear that jammy bastard grew four. “You’ve been following me,” he said, “looking for me. And now you’ve found me. It’s not my fault if you still haven’t found what you’re looking for.”

“I know what you are,” I snarled.

His eyes locked onto mine. “Your roommate?”

I shook my head and squeezed the hilt of my sword.

Baz stepped into my reach. “Tell me,” he spat.

I couldn’t.

“Tell me, Snow.” He stepped even closer. “What am I?”

I growled again and raised the blade an inch. “Vampire!” I shouted. He must have felt the force of my breath on his face.

He started giggling. “Really? You think I’m a vampire? Well, Aleister Crowley, what are you going to do about that?”

He slipped a flask out of his jacket and took a swig. I didn’t know that he’d been drinking—my sword dipped. I tried to remind myself to stay battle ready, and pulled it up again.

“Stake through the heart?” he asked, falling back into the corner and resting an arm on a pile of skulls. “Beheading, perhaps? That only works if you keep my head separate from my body, and even then I could still walk; my body won’t stop until it finds my head.… Better go with fire, Snow, it’s the only solution.”

I wanted to just slice him in two. Right then and there. Fucking finally.

But I kept thinking of Penelope. “How do you know he’s a vampire, Simon? Have you seen him drink blood? Has he threatened you? Has he tried to put you in his thrall?”

Maybe he had. Maybe that’s why I’d been following Baz around for six months.

And now I had him.

“Do something,” he teased. “Save the day, Snow. Or the night. Quick, before I … Hmm … what horrible thing shall I do? It’s too late for everyone down here—there’s just you to hurt, isn’t there? And I don’t think I’m in the mood to suck your blood. What if I accidentally Turned you? Then I’d be stuck with your pious face forever.” Baz shook his head and took another pull at his flask. “I don’t think undeath would improve you, Snow. It would just ruin your complexion.” He giggled again. Mirthlessly. And closed his eyes like he was exhausted.

He probably was. I was. We’d been playing cat and mouse in the Catacombs every night for weeks.

I dropped my sword but kept it unsheathed, then stepped out of my stance. “I don’t have to do anything,” I said. “I know what you are. Now I just have to wait for you to make a mistake.”

He winced without opening his eyes. “Really, Snow? That’s your plan? Wait for me to kill someone? You’re the worst Chosen One who’s ever been chosen.”

“Fuck off,” I said. Which always means I’ve lost an argument. I started backing out of the tomb. I needed to talk this through with Penelope; I needed to regroup.

“If I’d known it was this easy to get rid of you,” Baz called after me, “I would’ve let you catch up with me weeks ago!”

I headed for the surface, hoping that he couldn’t turn into a bat and fly after me. (Penny said that was a myth. But still.)

I could hear him singing, even after I’d been walking for ten minutes. “Ashes, ashes—we all fall down.”

* * *

I haven’t been back to the Catacombs since that night.…

I wait until I’m fairly sure everyone is in bed, hopefully asleep—then I sneak down to the White Chapel.

Two busts guard the secret door in the Poets Corner—the most famous of the modern mage poets, Carroll and Seuss. I’ve got some nylon rope, and I tie one end around Theodor’s neck.

The door itself, a panel in the wall, is always locked, and there isn’t any key. But all you have to do to open it is possess a genuine desire to enter. Most people simply don’t.

The door swings open for me. And closed behind me. The air is immediately colder. I light a wall torch and choose my first path.

Down in the winding tunnels of the Catacombs, I use every revealing spell I know, and every finding spell. (“Come out, come out, wherever you are! It’s show time! Scooby-Dooby-Doo, where are you!”) I call for Baz by his full name—that makes a spell harder to resist.

Magic words are tricky. Sometimes to reveal something hidden, you have to use the language of the time it was stashed away. And sometimes an old phrase stops working when the rest of the world is sick of saying it.

I’ve never been good with words.

That’s partly why I’m such a useless magician.

“Words are very powerful,” Miss Possibelf said during our first Magic Words lesson. No one else was paying attention; she wasn’t saying anything they didn’t already know. But I was trying to commit it all to memory.

“And they become more powerful,” she went on, “the more that they’re said and read and written, in specific, consistent combinations.

“The key to casting a spell is tapping into that power. Not just saying the words, but summoning their meaning.”

Which means you have to have a good vocabulary to do magic. And you have to be able to think on your feet. And be brave enough to speak up. And have an ear for a solid turn of phrase.

And you have to actually understand what you’re saying—how the words translate into magic.

You can’t just wave your wand and repeat whatever you’ve heard somebody saying down on the street corner; that’s a good way to accidentally separate someone from their bollocks.

None of it comes naturally to me. Words. Language. Speaking.

I don’t remember when I learned to talk, but I know they tried to send me to specialists. Apparently, that can happen to kids in care, or kids with parents who never talk to them—they just don’t learn how.

I used to see a counsellor and a speech therapist. “Use your words, Simon.” I got so bloody sick of hearing that. It was so much easier to just take what I wanted instead of asking for it. Or thump whoever was hurting me, even if they thumped me right back.

I barely spoke the first month I was at Watford. It was easy not to; no one else around here shuts up.

Miss Possibelf and a few of the other teachers noticed and started giving me private lessons. Talking-out-loud lessons. Sometimes the Mage would sit in on these, rubbing his beard and staring out the window. “Use your words!”—I imagined myself shouting at him. And then I imagined him telling me that it was a mistake to bring me here.

Anyway, I’m still not good with words, and I’m shit with my wand, so I get by with memorization. And sincerity—that helps, believe it or not. When in doubt, I just do whatever Penny tells me to.

I work my way carefully through the Catacombs, doing my level best with the spells I can make work for me.

I find hidden doorways inside hidden doorways. I find a treasure chest that’s snoring deeply. I find a painting of a girl with blond hair and tears pouring down her cheeks, actually pouring, like a GIF carved into the wall. A younger me would have stayed to figure out her story. A younger me would have turned this into an adventure.