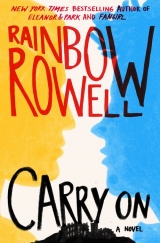

Текст книги "Carry On"

Автор книги: Rainbow Rowell

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

36

PENELOPE

My mum insisted on me having a mobile after what happened with the Humdrum.

For a few weeks this summer, she was saying I couldn’t come back to Watford at all, and my dad didn’t even try to talk her down. I think maybe he felt responsible. Like he should have figured the Humdrum out by now.

Dad spent the whole month of June in his lab, not even coming out to eat. Mum made his favourite biryani and left steaming plates of it outside his door.

“That madman!” Mum kept ranting. “Sending children to fight the Humdrum!”

“The Mage didn’t send us,” I tried telling her. “The Humdrum took us.” But that just made her angrier. I thought she’d want to work out how the Humdrum had done it. (It’s impossible to steal someone like that, to port them that far. The magic required … Even Simon doesn’t have enough.) But Mum refused to approach it intellectually.

It made me really glad that she doesn’t know the details of every other scrape Simon and I have got ourselves into—and got ourselves out of, I should add. We deserve some credit for that.

Mum probably would have cooled down sooner, if it weren’t for the nightmares.…

I didn’t scream when it actually happened:

One minute, Simon and I were in the Wavering Wood, gaping at Baz and Agatha—me holding Simon’s arm. And the next minute, we were in a clearing in Lancashire. Simon recognized it—he lived in a home there when he was a kid, near Pendle Hill. There’s this big sound sculpture that looks like a tornado, and I thought at first that the noise was the Humdrum.

I could already feel that we were in one of his dead spots.

Dad studies dead spots, so I’ve been to loads of them. They’re the holes in the magickal atmosphere that started appearing when the Humdrum did. Stepping into a dead spot is like losing a sense. Like opening your mouth and realizing you can’t make any noise. Most magicians can’t handle it. They start to lose their shit immediately. But Dad told me he’s never had as much magic as most magicians, so it isn’t as terrifying for him to think of losing it.

So Simon and I show up in this clearing, and I can feel straight away it’s a dead spot—but it’s more than that. It’s worse. There’s this weird whistling on the wind, and everything’s dry, so dry and hot.

Maybe it’s not a dead spot, I thought, maybe it’s a dying spot.

“Lancashire,” Simon said to himself.

And then—the Humdrum was there.

And I knew it was the Humdrum because he was the source of everything. Like the way you know that the sun is what makes the day bright. All the heat and dryness were coming from him. Or sucking towards him.

And neither of us, Simon or me, cried out or tried to run, because we were too much in shock: There was the Humdrum—and he looked just like Simon. Just like Simon when I first met him. Eleven years old, in grotty jeans and an old T-shirt. The Humdrum was even bouncing that red rubber ball that Simon never put down our first year.

The kid bounced the ball at Simon, and Simon caught it. Then Simon started screaming at the Humdrum, “Stop it! Stop it! Show yourself, you coward—show yourself!”

It was so hot, and so dry, and it felt like the life was getting sucked out of us, sucked right up through our skin.

Both of us had felt it before during the Humdrum’s attacks—that sandy, dry suck. We knew what he felt like, we recognized him. But we’d never seen the Humdrum before. (Now I wonder if that was the first time the Humdrum was able to show himself.)

Simon was sure the Humdrum was wearing his face just to taunt him. He kept howling at it to show its real face.

But the Humdrum just laughed. Like a little kid. The way little kids laugh once they’ve got started, and they can’t stop.

(I can’t really say why I think so or what it means, but I don’t think that the Humdrum appeared that way as a mean joke. I think that’s his true form. That he looks like Simon.)

The suck was too much. I looked down at my arm, and there was yellow fluid and blood starting to seep through my pores.

Simon was shouting. The Humdrum was laughing.

I reached out and took the ball from Simon and threw it down the hill.

The Humdrum stopped laughing then—and immediately darted after the ball. The second he turned away from us, the sucking stopped.

I fell over.

Simon picked me up and threw me over his shoulder (which is pretty amazing, considering I weigh as much as he does). He pushed forward like a Royal Marine, and as soon as he was out of the dead spot, he shifted me around to the front—and big bony wings burst out of his back. Sort-of wings. Misshapen and overly feathered, with too many joints …

There’s no spell for that. There are no words. Simon just said, “I wish I could fly!” and he made the words magic.

(I haven’t told anyone that part. Magicians aren’t genies; we don’t run on wishes. If anyone knew that Simon could do that, they’d have him burnt at the stake.)

We were both hurt, so I tried to cast healing spells. I kept thinking that the Humdrum would haul us back as soon as he found his ball. But maybe that wasn’t the sort of trick he could manage twice in one day.

Simon flew as far as he could with me clinging to him—stuck to him with spells and fading fast. Then I think he realized how mad we looked and landed near a town.

We were going to take a train, but Simon couldn’t get his wings to retract. Because they weren’t wings. They were bones and feathers and magic—and will.

This is what my nightmares are about:

Hiding in a ditch along the side of the road. Simon’s exhausted. And I’m crying. And I’m trying to gather the wings up and push them into his back, so that we can walk into town and catch a train. The wings are falling apart in my hands. Simon’s bleeding.

In my nightmares, I can’t remember the right spell.…

But I remembered it that day. It’s a spell for scared children, for sweeping away practical jokes and flights of fancy. I pressed my hand into Simon’s back and choked out, “Nonsense!”

The wings disintegrated into clumps of dust and gore on his shoulders.

Simon picked someone’s pocket at the train station, so we could buy tickets. We slept on the train, leaning against each other. And when we got back to Watford, it was in the middle of the end-of-year ceremony, and Mum and Dad were there, and they dragged me home.

They almost didn’t let me come back to school this autumn—they tried to talk me into staying in America. Mum and I yelled at each other, and we haven’t really talked properly since.

I told my parents I couldn’t miss my last year. But we all knew that what I really meant was that I wouldn’t let Simon come back without me.

I said I’d walk back to Watford, that I’d find a way to fly.

Now they make me carry a mobile phone.

37

AGATHA

Watford is a quiet place if you’re not dating Simon Snow—and if you’ve spent so many years with Simon Snow that you never bothered making other friends.

I don’t have a roommate. The roommate the Crucible gave me, Philippa, got sick our fifth year and went home.

Simon said Baz did something to her. Dad said she had sudden, traumatic laryngitis—“a tragedy for a magician.”

“That would be a tragedy for anyone,” I said. “Normals talk, too.”

I don’t really miss Philippa. She was dead jealous that Simon liked me. And she laughed at my spellwork. Plus she always painted her nails without opening a window.

I do have friends, real friends, back home, but I’m not allowed to tell them about Watford. I’m not even able to tell them—Dad spelled me mum after he caught me complaining to my best friend, Minty, about my wand.

“I just said it was a hassle carrying it everywhere! I didn’t tell her it was magic!”

“Oh for snakes’ sake, Agatha,” Dad said.

My mother was livid. “You have to do it, Welby.”

So Dad levelled his wand at me: “Ix-nay on the atford-Way!”

It’s a serious spell. Only members of the Coven are allowed to use it. But I suppose it was a serious situation: If you tell Normals about magic, they all have to be tracked down and scoured. And if that’s not possible, you have to move away.

Now Minty (we met in primary school, that’s actually her first name, isn’t it lush?) thinks I go to a super-religious boarding school that doesn’t allow the Internet. Which is all true, as far as I’m concerned.

Magic is a religion.

But there’s no such thing as not believing—or only going through the motions on Easter and Christmas. Your whole life has to revolve around magic all the time. If you’re born with magic, you’re stuck with it, and you’re stuck with other magicians, and you’re stuck with wars that never end because people don’t even know when they started.

I don’t talk like this to my parents.

Or to Simon and Penny.

Ix-nay on my ue-feelings-tray.

* * *

Baz is walking by himself across the courtyard. We haven’t talked since he’s been back.

We’ve never really talked, I guess. Even that time in the Wood. Simon burst in before we could get anywhere, and then Simon burst out again.

(Just when you think you’re having a scene without Simon, he drops in to remind you that everyone else is a supporting character in his catastrophe.)

As soon as Simon and Penny disappeared that day, Baz dropped my hands. “What the fuck just happened to Snow?”

Those were his last words to me.

But he does still watch me in the dining hall. It makes Simon mental. This morning, Simon got fed up and slammed his fork down, and when I looked over at Baz, he winked.

I hurry to catch up with him now. The sun is setting, and it’s making his grey skin look almost warm. I know it’s setting my hair on fire.

“Basil,” I say coolly, smiling like his name’s a secret.

He turns his head slightly to see me. “Wellbelove.” He sounds tired.

“We haven’t talked since you’ve been back,” I say.

“Did we talk before that?”

I decide to be bold. “Not as much as I’d like.”

He sighs. “Crowley, Wellbelove, there must be a better way to get your parents’ attention.”

“What?”

“Nothing,” he says, walking ahead.

“Baz, I thought—I thought you might need someone to talk to.”

“Nope, I’m good.”

“But—”

He stops and sighs, rubbing his eyes. “Look … Agatha. We both know that whatever you and Snow are squabbling about, you’ll soon work it out and be back to your golden destiny. Don’t complicate it.”

“But we’re not—”

Baz has started walking again. He’s limping a little. Maybe that’s why he isn’t playing football. I keep following him.

“Maybe I don’t want a golden destiny,” I say.

“When you figure out how to sidestep destiny, let me know.” He’s walking as fast as he can with his limp, and I decide not to run to keep up with him. That would look appalling.

“Maybe I want something more interesting!” I call out.

“I’m not more interesting!” he shouts back, without turning his head. “I’m just wrong for you. Learn the difference.”

I bite down on my bottom lip and try not to cross my arms like a 6-year-old.

How does he know he’s wrong for me?

Why does everyone else think they know where I belong?

38

BAZ

Snow has been staring at me all day—for weeks now—and I’m just really not up for it. Maybe Aunt Fiona was right; I should have stayed home longer and rested up. I feel like complete shit.

Like I can’t get full, and I can’t get warm—and last night, I had some sort of attack in the Catacombs. It’s so fucking dark down there. And even though I can see in the dark, I felt like I was back in that stupid numpty coffin.

I couldn’t stay underground any longer. I caught six rats, banged their heads on the floor, tied their tails in a knot, then brought them back upstairs and drained them in the courtyard under the stars. May as well have sent an engraved announcement to the whole school, telling them I’m a vampire. A vampire who’s afraid of the dark, for Crowley’s sake.

I threw the rat carcasses to the merwolves. (They’re worse than rats. I’d drain every one of them if the taste didn’t stay in my mouth for weeks. Gamy and fishy.)

Then I slept like the dead for nine hours, and it still wasn’t enough. I’ve been asleep on my feet since lunch, and I can’t exactly go up to my room to take a nap. Snow would probably sit across from me and watch.

He’s been following me everywhere since I got back. He hasn’t been this persistent since our fifth year—he even followed me to the boys’ toilet yesterday and pretended he just needed to wash his hands.

I don’t have the strength for it.

I feel 15 again, like I’m going to give in if he gets too close—kiss him or bite him. The only reason I got through that year was that I couldn’t decide which of those options would finally put me out of my misery.

Probably Snow himself would put me out of my misery if I tried either one.

Those were my fifth-year fantasies: kisses and blood and Snow ridding the world of me.

I watched the football practice this afternoon, just for an excuse to sit down, then slipped away from the team when everyone else headed for dinner.

Wellbelove catches me in the courtyard and tries to suck me into her maiden-fair drama, but I haven’t got time for the pain. I heard Miss Possibelf say that the Mage is coming back to Watford tomorrow—and I still haven’t snuck up to his office. (Probably because it’s an idiotic idea.) But if I go up there and take something, it will at least get Fiona off my back for a while.

I haul myself to the Weeping Tower, and skip the spiral staircase to take the staff elevator up to the very top.

I walk past the door to the headmaster’s rooms. When my mother was headmistress, I lived with her here. I was just a toddler. Father would come in most weekends, and we’d all go back to the house in Hampshire every summer.

My mother used to let me play in her office while she worked. She’d come get me from the nursery, and I’d spread my Lego bricks out on her rug.

When I get to the headmaster’s office, the door opens easily for me—the Mage never took down the wards my mother cast to let me in. I can get in his rooms, too. (I snuck in once and found myself puking in his toilet.) Fiona would have me inspecting his chambers every night, but I’ve told her we have to save that trick until we really need it. Until we can use it. And not just to leave steaming bags of shit in his bed.

“Furthermore, Fiona, I’m not shitting in a bag.”

“I’ll do the shitting, you knob; it can be my shit.”

My stomach clenches when I walk into the office. When I see my mother’s desk. It’s dark in here—the curtains are drawn—so I light a fire in my palm and hold it out in front of me.

It terrifies my stepmother when I do this. “Basilton, don’t. You’re flammable.”

But bringing fire is as easy for me as breathing; it hardly takes any magic, and I always feel utterly in control. I can make it twist through my fingers like a snake. “Just like Natasha,” my father always says. “He’s got more fire than a demon.”

(Though Father did draw a hard line when he caught me smoking cigarettes in the carriage house. “For Crowley’s sake, Baz, you are flammable.”)

The headmaster’s office looks exactly the same as it did when I played here. You’d think the Mage would have thrown all my mother’s things out and hung up Che Guevara posters—but he didn’t.

There’s dust on his chair. On my mother’s chair. And thick dust on the computer keyboard—I don’t think he even uses it. He’s not the sitting, typing type, the Mage. He’s always stalking around or swinging a sword, or doing something to justify his Robin Hood costume.

I open his top drawer with my wand. Nothing here … Dried-up office supplies. A phone charger.

My mother kept tea in this drawer, and mint Aero bars and clove drops. I lean in to see if I can smell them—I can smell things other people can’t. (I can smell things no people can.) (Because I’m not a person.)

The drawer smells like wood and leather. The room smells like leather and steel and the forest, like the Mage himself. I open the other drawers with my hand. There aren’t any booby traps. There’s nothing personal at all. I’m not even sure what to take for Fiona. A book, maybe.

I hold my flame up to the bookshelves and think about blowing, just setting the whole room on fire. But then I notice that the books are all out of order. Obviously out of order. Stacked, instead of set on their shelves—some of them lying in piles on the floor. I feel like putting them back, sorting them by subject the way my mother used to. (I was always allowed to touch her books. I was allowed to read any book, as long as I put it back in its place and promised to ask if something confused or frightened me.)

Maybe I should take advantage of the fact that the books are out of order: No one will notice if one goes missing—or several. I reach for one with a dragon embossed on the spine; the dragon’s mouth is open, and fire spews out forming the title: Flames and Blazes—The Art of Burning.

A shaft of light widens on the shelf before me, and I jerk around, sending the book sailing, pages flapping. Something flies out as the book hits the floor.

Snow is standing in the doorway. “What are you doing here?” he demands. His blade is already out.

I’ve seen that sword in action enough, you’d think I’d be terrified—but instead it’s reassuring. I’ve dealt with this, with Snow, before.

I must truly be exhausted, because I tell him the truth: “Looking for one of my mother’s books.”

“You’re not supposed to be in here,” he says, both hands on his sword.

I hold my light higher and step away from the shelves. “I’m not hurting anything. I just want a book.”

“Why?” He looks down at the book lying between us and rushes forward, abandoning his stance to beat me to it. I lean back against the shelves and swing one ankle over the other. Snow’s crouching over the book. He probably thinks it’s a clue, the thing that will blow my conspiracy wide open.

He stands again, staring at a small piece of paper in his hand. He looks upset. “Here,” he says softly, holding it out to me. “I’m … sorry.”

I take the paper, a photograph, and he watches me. I’m tempted to shove it in my pocket and look at it later, but curiosity gets the best of me, and I hold it up.…

It’s me.

Down in the crèche, I think. (Watford used to have a staff nursery and day school; it’s where the vampires struck.)

I’m just a baby in this photo. Three or four years old, wearing soft grey dungarees with bloomer bottoms, and white leather boots. My skin is the shocking thing: a stark reddish gold against my white collared shirt and white socks. I’m smiling at the camera, and someone’s holding my fingers—

I recognize my mother’s wedding ring. I recognize her thick, rough hand.

And then I can remember her hand. Resting on my leg when she wanted me to be still. Holding her wand precisely in the air. Slipping into her desk drawer to get a sweet and popping it into her mouth.

“Your hands are scratchy,” I’d say when she cupped one around my cheek.

“They’re fire-holders’ hands,” she’d say. “Flame throwers’.”

My mother’s hands scuffing my cheek. Tucking my hair behind my ears.

My mother’s hands held aloft—setting the air of the nursery on fire while a chalk-skinned monster buried his teeth in my throat.

“Baz…,” Snow says. He’s picked up the book and is holding it out to me.

I take it.

“I need to tell you something,” he says.

“What?” Since when do Snow and I have anything to tell each other?

“I need to talk to you.”

I raise my chin. “Talk, then.”

“Not here.” He sheathes his blade. “We’re not supposed to be here, and … what I have to tell you is sort of private.”

For a moment—not even a moment, a split second—I imagine him saying, “The truth is, I’m desperately attracted to you.” And then I imagine myself spitting in his face. And then I imagine licking it off his cheek and kissing him. (Because I’m disturbed. Ask anyone.)

I “Make a wish!” the flame out of my hand, tuck the photo into the book, and the book under my arm. “Lucky for us,” I say, “we have our own suite at the top of a turret. Private enough for you?”

He nods, embarrassed, and gestures for me to walk ahead of him. “Just come on,” he says.

I do.

39

SIMON

I’d just caught my enemy red-handed, breaking into the Mage’s office. I could have got him expelled for this. Finally.

And instead I gave him the thing he came to steal, then asked him if we could have some alone time—all because of a baby picture.

But the look on Baz’s face in that picture … Smiling just because he was happy, with cheeks like red apples.

And the look on his face when he saw it. Like someone blew a horn and all his walls crumbled.

We walk back to our room, and it’s awkward; we don’t have any experience walking with each other, even though we’re usually headed in the same direction. We keep our distance on the stairs, then move even farther away as we cross the courtyards. I keep wanting to get my sword back out.

Baz has worked himself up to a full-on strop by the time we get to our room. He slams the door shut behind us, sets the book on his bed, then crosses his arms. “Fine, Snow. We’re alone. Whatever you have to say—say it.”

I cross my arms, too. “All right,” I say, “just … sit down, okay?”

“Why should I sit down?”

“Because you’re making me uncomfortable.”

“Good,” he says. “You should be glad I’m not making you bleed.”

“For Christ’s sake,” I say. I only swear like a Normal when I’m at my wit’s end. “Could you just calm down? This is important.”

Baz shakes his head, exasperated, but sits at the end of his bed, frowning at me. He has these droopy dog eyes that always look like they’re peeking out from under his eyelids, even when his eyes are wide open. And his lips naturally turn down at the corners. It’s like his face was designed for pouting.

I walk over to my book bag and pull out a notebook. I wrote down as much as I could the day after Baz’s mum came to see me; I thought I was writing it all down to share with the Mage.

I sit on my bed, facing him, and he reluctantly shifts to sit across from me.

“All right,” I say, “look. I don’t want to tell you this. I don’t even know if I should. But it’s your mum, and I don’t think it’s right to keep it from you.”

“What about my mother?” His arms unfold, and he leans forward, grabbing at my notebook.

I whip the notebook away. “I’m telling you, okay? Just listen.”

His eyes narrow.

I’m stupidly flustered. “When you were gone—you were gone when the Veil lifted.”

He guesses it immediately—his nostrils flare, and his eyes go a little wild—he’s so fucking smart, I don’t know how I’m ever going to get the best of him.

“My mother…,” he says.

“She was looking for you. She kept coming back. Here. Where were you that she couldn’t find you?”

“My mother came through the Veil?”

“Yeah. She said she was called here, to our room, that this was your place. And she was pretty hacked off that you weren’t here. Wanted to know whether I’d hurt you.”

“She talked to you?”

“Yeah. I mean—yes.” I run my hands through my hair. “She came looking for you and scared the living shit out of me, asking if I’d hurt you. And then she said that the Veil was closing.…” I look down at my notebook.

Baz grabs it from me, scanning the page hungrily, then hurls it back at my chest. “You write like an animal. What did she say?”

“She said that…” My voice falters. “That her killer walks. That you should find Nicodemus and bring her peace.”

“Bring her peace?”

I don’t know what more to say. His face is in agony.

“But she killed the vampires,” he says.

“I know.”

“Does she mean the Humdrum?”

“I don’t know.”

“Tell me again.”

I look back down at my notes. “Her killer walks, but Nicodemus knows. Find Nicodemus and bring her peace.”

“Who’s Nicodemus?” Baz demands. Fierce and imperious, just like his mother.

“She didn’t say.”

“What else?” he asks. “Was there anything else?”

“Well … she kissed me.” My hand jerks up, and I brush my fingertips over my forehead. “She told me it was for you, to give to you.”

He clenches his fists at his sides. “Then what?”

“Then she left,” I say. “She came back one more time, that same night, the last night before the Veil fell”—Baz looks like he wants to choke me—“and she was different, sadder, like she was crying.” I look down at my notes. “And I couldn’t see her that time, but she said, ‘My son, my rosebud boy.’ She said that a few times, I think. And then she called me by my name and said she never would have left you. And then: ‘He said we were stars.’”

“Who said? Nicodemus?”

“I guess, I don’t know.”

Baz squeezes his fists tight, and his voice comes out of him in a tight roar. “Who. The fuck. Is Nicodemus.”

“I don’t know,” I say. “I thought you’d know.”

He gets off the bed and starts prowling about the room. “My mother came back. She came back to see me. And you talked to her instead. Unbelievable.”

“Well, where were you? Why couldn’t she find you?”

“I was indisposed! It’s none of your business!”

“Well, I hope your secret trip was worth it!” I shout. “Because your mother came for you! She came and she came and she came—and you were off planning your hopeless rebellion!”

He stops pacing, then charges towards me, his hands reaching for my neck. And I’m more scared for him than I am for myself, even though I know he wants to kill me. Because if he touches me, he’ll be cast out. The Anathema.

I jump to my feet and catch his wrists. They’re cold. “Baz, you don’t want to hurt me. Do you.” He strains against my grip. He’s panting with rage. “You don’t want to hurt me,” I say, trying to push him back. “Isn’t that right? I’m sorry. Look at me, I’m sorry.”

His grey eyes focus, and he steps back, snatching his arms away. We both glance around the room, waiting for the Anathema to kick in.

There’s a knock at the door, and we both jump.

“Simon?” I hear Penny say.

Baz arches an eyebrow, and I can practically hear him thinking, Interesting. I shove past him and open the door. “Penny, what’re you—?”

She’s been crying. She starts again—“Simon”—and rushes into my arms. I slowly put my arms around her and look up at Baz, waiting for him to raise the alarm.

He shakes his head, like it’s all too much for him. “I’ll leave you alone,” he says, sliding past us out the door. I hate to think of how he’ll use this against Penelope, or me—but right now I’ve got Penny sobbing into my shirt.

“Hey,” I say, patting her back. I’m not good at hugging, she knows that, but she must not care right now. “Hey, what’s wrong?”

She pulls back and wipes her face on her sleeve. She’s still wearing her coat. “My mum…” Her face is all crumpled. She wipes it on her sleeve again.

“Is she okay?”

“She’s not hurt—nobody’s hurt. But she told me that Premal came yesterday.” Penny’s talking too fast, and still crying. “He came for the Mage with two more of his Men, and they wanted to search our house.”

“What? Why?”

“The Mage sent them. Premal said it was a routine search for banned magic, but Mum said there’s no such thing as a routine search, and she’d be damned to Slough before she let the Mage treat her like she was an enemy of the state. And then Premal said it wasn’t a request. And Mum said they could come back with an order from the Coven”—Penny’s shaking in my arms—“and Prem said that we’re at war, and that the Mage is the Mage, and what did Mum have to hide, anyway? And Mum said that wasn’t the point. The point was civil liberties, and freedom, and not having your 20-year-old son showing up at your house like Rolf in The Sound of Music. And I’m sure Premal was humiliated and not acting like himself—or maybe just acting more like his tosser self than usual—because he said he’d be back, and that Mum had better change her mind. And Mum said he could come back as a Nazi and a fascist, but not as her son.” Penny’s voice breaks again, and she covers her face in her arms, elbowing me in the chin.

I pull my head back and hold on to her shoulders. “Hey,” I say, “I’m sure this is just something that got out of hand. We’ll talk to the Mage.”

She jerks away from me. “Simon—no. You can’t talk to him about this.”

“Pen. It’s the Mage. He’s not going to hurt your family. He knows you’re good.”

She shakes her head. “My mum made me promise not to tell you, Simon.”

“No secrets,” I say, suddenly defensive. “We have a pact.”

“I know! That’s why I’m here, but you cannot tell the Mage. My mother’s scared, and my mother doesn’t get scared.”

“Why didn’t she just let them search the house?”

“Why should she?”

“Because,” I say, “if the Mage is doing this, he has a reason. He doesn’t just hassle people. He doesn’t have time for that.”

“But … what if they found something?”

“At your house? They wouldn’t.”

“They might,” she says. “You know my mum. ‘Information wants to be free.’ ‘There’s no such thing as a bad thought.’ Our library is practically as big as Watford’s and better stocked. If you wanted to find something dangerous in there, I’m sure you could.”

“But the Mage doesn’t want to hurt your family.”

“Who does he want to hurt, Simon?”

“People who want to hurt us!” I say. I practically shout it. “People who want to hurt me!”

Penny folds her arms and looks at me. She’s mostly stopped crying. “The Mage isn’t perfect. He’s not always right.”

“No one is. But we have to trust him. He’s doing his best.” As soon as I say it, I feel a pound of guilt settle in my stomach. I should have told the Mage about the ghost. I should have told Penny. I should have told them both before I told Baz. I could be spying for the wrong side.

“I need to think about this,” Penny says. “It’s not my secret to tell—or yours.”

“All right,” I agree.

“All right.” A few more tears well up on her, and she shakes her head again. “I should go. I can’t believe Baz hasn’t come back with the house master yet. They probably think he’s lying—”

“I don’t think he’s snitching on you.”

She huffs. “Of course he is. I don’t care. I have bigger worries.”

“Stay for a bit,” I say. If she stays, I’ll tell her about Baz’s mum.

“No. We can talk about this tomorrow. I just needed to tell you.”

“Your family will be safe,” I say. “You don’t have to worry about it. I promise.”

Penelope looks unconvinced, and I half expect her to point out how worthless my words have been so far. But she just nods and tells me she’ll see me at breakfast.