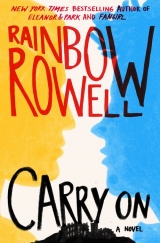

Текст книги "Carry On"

Автор книги: Rainbow Rowell

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

55

BAZ

Snow was a wreck at dinner.

Which I might have enjoyed if I wasn’t so desperate for him to stay.

Everything on his plate seemed to confuse him, and he alternated between staring at his food miserably and vacuuming it up because he was clearly ravenous.

Daphne went out of her way to make him feel comfortable, and the children just stared at him. Even they’ve heard of the Mage’s Heir.

Father seems to think I have some dark plan at work. (I guess I do have a dark plan, but this time it has nothing to do with disabling Snow.) He—Father—pulled me aside after dinner and asked if I wanted him to call in the Families for assistance.

“No,” I said. “Please don’t. Snow’s just here for a school project.”

Father practically winked.

I’ve thought about telling him. That Mother came back for me. But what if he asks why she didn’t come back to him? What if he takes it to the Families? They’d never understand why I was working with Snow and Bunce. And right now, Snow and Bunce seem like the best allies I could have. They’re relentless once they set their minds to something. Completely trustworthy, with no sense of self-preservation. I’ve watched these two uncover plots and beat back monsters time and again.

Snow is still eating dinner. Daphne keeps offering extra helpings, out of politeness, and Snow keeps accepting them.

I’ve never actually sat at a table with Snow before. I let myself watch him, and let myself enjoy it, at least for a few minutes. I keep doing that, since this all started—indulging myself. (What’s that they say about having dessert first if you’re on the Titanic?)

Snow’s table manners are atrocious—it’s like watching a wild dog eat. A wild dog you’d like to slip the tongue.

After dinner, we go to the library and I show him what I’ve found on vampires. He keeps moving away from me, and I pretend not to notice. We should probably call Bunce and see what she thinks of all this—I’ll suggest it tomorrow.

There’s nothing in our library about any Nicodemus. I’ve already searched, but I do it again. I stand at the door and cast, “Fine-tooth comb—Nicodemus Petty!” None of the books come flying out of the shelves.

We do find a few mentions of the Petty family, so we read those. They’re an old East End family, and a big one, and every few generations, they turn out a powerhouse like Ebb. If Snow hadn’t come along, Ebb might be the most powerful magician in our world—and to think she wastes it all on goats and moping.

“Do you think it would have made it into The Record?” Snow asks. “When Nicodemus crossed over?”

“I don’t know,” I say. “Maybe not. They probably wanted to keep it hush-hush, and it doesn’t seem like he hurt anybody.”

“What’s the point of becoming a vampire,” Snow says, “if you’re not planning to hurt anybody?”

“What’s the point of becoming a vampire?” I ask.

“You tell me.”

I swallow my temper and then swallow it again, and keep looking through a book.

Snow sits down across from me at the small table, pulling up a quilted chair. “No,” he says. “I’m being serious. Why would Nicodemus have done it?”

“You’re asking me to pose a theory?”

He nods.

“To become stronger,” I say. “Physically.”

“How much stronger?” Snow asks.

I shrug. “You’d have to ask him. I wouldn’t know how to compare.” Because I don’t remember being normal.

“What else?” he asks.

“To enhance himself … his senses.”

“Like, to see better?”

“In the dark,” I say. “And hear more. And smell more sharply.”

“To live forever?”

I shake my head. “I don’t think so. I don’t think it works like that. But he wouldn’t ever … be sick.”

Snow lowers his eyebrows. “When you look at it that way, why doesn’t everyone cross over?”

“Because it’s death,” I say.

“It clearly isn’t.”

“They say your soul dies.”

“That’s tosh,” he says.

“How would you know, Snow?”

“Observation.”

“Observation,” I say. “You can’t observe a soul.”

“You can over time,” he says. “I think I’d know—”

“It’s death,” I say, “because you need to eat life to stay alive.”

“That’s everyone,” he says. “That’s eating.”

“It’s death,” I say, refusing to raise my voice, “because when you’re hungry, you can’t stop thinking about eating other people.”

Snow sits back. His mouth is open—because no one ever taught him to close it. He pushes at his bottom lip with his tongue. I think about licking blood from it.

“It’s death,” I say, looking back down at my book, “because you look at other people, living people, and they seem really far away. They seem like something else. The way that birds seem like something else. And they’re full of something you don’t have. You could take it from them, but it still won’t be yours. They’re full, and … you’re hungry. You’re not alive. You’re just hungry.”

“You have to be alive to be hungry,” Snow says. “You have to be alive to change.”

“Maybe you should write a book about vampires,” I say.

“Maybe I should. Apparently, I’m the world’s leading expert.”

When I look up, Snow’s staring right at me.

I can feel the cross around his neck, like static in my salivary glands, but it’s never been less discouraging. I could knock him over right now. (Kiss him? Kill him? Improvise?)

“You should ask your parents,” Snow says.

“Whether I’m alive?” Fuck. I didn’t mean to say it like that. To concede, even a little.

Snow closes his mouth. Swallows. That’s where I’d bite him, right in the throat.

“I meant,” he says, “you should ask them if they remember Nicodemus. Maybe they know where he is.”

“I’m not asking my parents about the only magician to run off to join the vampires. Are you a complete moron?”

“Oh,” he says. “I guess I didn’t think about it that way.”

“You didn’t think—” I say. And then—“Oh. Oh, oh, oh.”

SIMON

Baz is running up the steps again, so I’m running behind him. We haven’t seen anyone else since dinner. This house is so big, it could absorb a mob and still seem empty.

We’re in a different wing now. Another long hallway. Baz stops in front of a door and starts casting disarming spells. “So predictably paranoid,” he mutters.

“What’re we doing?” I ask.

“Looking for Nicodemus.”

“You think he might live here?”

“No,” he says. “But—”

The door opens, and we’re in another creepy goth bedroom. This one is like Goth Through the Ages, because on top of the gargoyles, there are posters of ’80s and ’90s rock stars wearing lots of black eyeliner. And somebody’s even written Never Mind the Bollocks in yellow spray paint on one wall, ruining the antique black-and-white wallpaper.

“Whose room is this?” I ask.

Baz is crouching next to a bookshelf. “My aunt Fiona’s.”

I step back into the doorway. “What are we doing here?”

“Looking for something…” A second later, he pulls out a big purple scrapbook with Remember the Magic embossed on the front in gold. “Aha!” he says. “I’m pretty sure Fiona went to school with Ebb. I’ve heard her talk about her. Disparagingly, I promise you. She never mentioned Ebb’s brother, though.…”

Baz is flipping through the pages. I crouch down next to him. “What is that?”

“It’s a memory book,” he says. “They used to give them out at Watford before the Mage took over. At your leavers ball. It’s got class pictures from every year and little stories.…” He holds the book open to a page full of photos. It makes me wish I had something like it—I don’t have any pictures of myself or my friends. Agatha has a few, I think.

Baz has turned to the back of the book, and he’s poring over a big class picture, squinting.

Underneath the picture, someone has taped in a few snapshots. “Look,” I say, pointing at a photo of a girl sitting against a tree—the yew tree. She’s got mad dark hair with a blond streak, and she’s grinning with her nose crunched up and her tongue between her teeth. There’s a rawboned boy sitting next to her with his arm slung around her shoulders. “Ebb,” I say. Because the straight blond hair is the same. And the cliff’s-edge cheekbones. But I’ve never seen Ebb looking so cocksure of herself—and I can’t imagine her smirking like that. Under the picture, someone’s written Me and Nickels, and dotted the i with a heart.

“Fiona!” Baz says, snapping the book closed.

I take it from him and open it again, settling down on the floor and leaning against the bed. There are a few pages for each year Fiona was in school—with big class photos and blank pages where you can put other pictures and certificates. It’s not hard to spot Fiona in each posed class photo—that white streak must be natural—and then to find Ebb and Nicodemus, always standing next to each other, looking almost exactly alike, but completely different. Ebb looks like Ebb, gentle and unsure, in every picture. Nicodemus looks like he’s about to hatch a plan. Even as a first year.

I find another snapshot of Nicodemus and Baz’s aunt, this time posing in old-fashioned costumes. “Did you know Watford used to have a drama society?” I ask.

“Watford had a lot of things before the Mage.” Baz takes the book from me and puts it back on the shelf. “Come on.”

“Where are we going?”

“Now? To bed. Tomorrow? London.”

I must be tired, because neither of those statements makes sense to me.

“Come on,” Baz says. “I’ll show you to your room.”

* * *

My room turns out to be the creepiest one yet:

There’s a dragon painted on the archway around the door, and its face is charmed to glow and follow you in the dark.

Plus there’s something under the bed.

I don’t know exactly what, but it moans and clicks and makes the bedposts shake. I end up at Baz’s door, telling him I’m going back to Watford.

“What?” He’s half asleep when he comes to the door. And flushed—he must have gone hunting after I went to bed. Or maybe they keep kennels for him on the grounds.

“I’m leaving,” I say. “That room is haunted.”

“The whole house is haunted, I told you.”

“I’m leaving.”

“Come on, Snow, you can sleep on my couch. The wraiths don’t hang out in here.”

“Why not?”

“I creep them out.”

“You creep me out,” I mutter, and he throws one of his pillows into my face. (It smells like him.)

I realize, as I’m settling in on his couch, that I don’t mean it. About him creeping me out.

I used to mean it. I usually do.

But he’s the most familiar thing in this house, and I fall asleep better, listening to Baz breathe, than I have since winter break started.

56

FIONA

All right, Natasha, I know I shouldn’t have told him anything.

You wouldn’t have done.

Swans right into my flat, looking for trouble. Being trouble, every bloody moment he’s alive.

“Tell me about Nicodemus,” he says, like he already knows everything he needs to.

He knows he’s my favourite; that’s the problem. He would be, even if you’d had a litter of pups. Cocky as Mick Jagger, that one. And smart as a horsewhip.

“Who’s been talking to you about Nicodemus?” I ask.

He sits at my grotty little table and starts drinking my tea, dunking the last of my lavender shortbread in it. “Nobody,” he says. Liar. “I’ve just heard that he’s like me.”

“A scheming brat?

“You know what I mean, Fiona.”

“Nice suit, Basil, where are you headed?”

“Dancing.”

He’s all kitted out in his finest. Spencer Hart, if I’m not wrong. Like he’s here to collect his BAFTA.

I sit across from him. “He’s nothing like you,” I say.

“You should have told me,” he says. “That I wasn’t the only one.”

“He chose it. He crossed over.”

“What does it matter whether I chose it, Fiona? The result is the same.”

“Not hardly,” I tell him. “He left our world. Left. Said he was going to evolve.”

He said he was going to be more than magic.

“You’re powerful enough now, Nicky.”

“What do we say about ‘enough,’ Miss Pitch?”

His school tie tucked into his jacket pocket. That cruel, cool smile.

“He betrayed us, Basil.” I feel the old anger—the old everything—rising up in my throat.

“And he was stricken,” my nephew says.

“Because he was a betrayer,” I say.

“Because he was a vampire,” Baz says, and I can’t help it—that word still makes me recoil.

It wasn’t supposed to be me, Natasha. Telling this boy how to make his way in the world. I’m no good at this. Look at me. Thirty-seven years old, rolling my own joints in my dressing gown, eating bikkies for breakfast whenever I manage to get up—I’m a disgrace.

What would you say to him if you were here?

No … Never mind. I know what you’d say—and you’re wrong.

That’s one way I’ve bettered you. I was weak enough to give your son a chance. And look at him now—he may be dead, but he isn’t lost. He’s dark as pitch and sharp as a blade, and he’s full of your magic. He’s a bonfire. He’d make you proud, Tasha.

“You’re not going to be stricken, Basil,” I tell him. “Is that what this is about? No one knows about you, and even if they find out—which they won’t—they’ll know we can’t spare you. The Families are finally ready to strike back at the Mage. It’s all happening.”

He licks his bottom lip and looks out my little window. The sun’s still out, and I know it bothers him, even if he won’t complain. I unhook the curtain, and my kitchen falls into shadow.

“Is he still alive?” Baz asks. “Nicodemus?”

“I think so. In a matter of speaking. I haven’t heard any different.”

“Would you have heard?”

There’s a pack of fags on the table. I light one with my wand and take a few good drags, tapping the ash out on my saucer. “You know that the Families use my London connections.…”

“What does that mean, Fiona?”

“I talk to people here who no one else wants to. Undesirables. I’m not worried about getting my hands dirty now and then.”

Then, sister, he cocks one of your eyebrows at me.

I spit out some smoke. “Pfft. Not like that, you perv.”

“So Nicodemus is an undesirable,” he says.

“We’re not permitted to talk about him. It’s mage law.”

“Would you cut me off so easily?”

“Oh, fuck, Baz, you know I wouldn’t. What are you on about?”

“I can’t help but be curious.” He leans towards me over the table. “Is he alive? Does he hunt? Has he aged? Has he Turned anyone?”

“Nicodemus Petty doesn’t have any answers for you, boyo.” I’m jabbing my cigarette at him, so I put it out before I accidentally torch him. “He’s a two-bit gangster—a third-tier thug in a Guy Ritchie movie. He thought he was going to be the über-mage, but he ended up shooting dice in the back room of some vampire bar in Covent Garden. He threw his whole life away, and hurt everyone who loved him—and there’s nothing you can learn from him, Basil. Other than how to be a shitty vampire.”

Baz’s eyebrow is still raised. He drinks the rest of my tea. “Fine,” he says. “You’ve made your point.”

“Good. Go home and study.”

“I’m on break.”

“Go home and figure out how to take down the Mage.”

“I told you. I’m going dancing.”

I look at his suit again and his shiny black shoes. “Basil. Have you met a bloke?”

He smiles, and he’s made of trouble. We should have dropped him in the Thames in a bag of stones. We should have left him out for the fairies.

“Something like that.”

57

AGATHA

I’m sitting at Penelope’s counter, spreading pink icing on another gingerbread lady.

“Why do the gingerbread girls have to wear pink?” Penny asks.

“Why should the gingerbread girls feel like they shouldn’t wear pink?” I say. “I like pink.”

“Only because you’ve been conditioned to like it by Barbies and gendered Lego.”

“Lay off, Penny. I’ve never played with Lego.”

Hanging out with Penny is actually going better than I thought. When she cornered me in the courtyard before we left for break, I thought she was going to chew me out for abandoning Simon.

“Hey,” she said, “I heard that Simon isn’t coming over for Christmas.”

“Because we’re not dating anymore, Penelope. Happy?”

“Generally,” she said, “but not because you broke up.”

It’s impossible to end a conversation with Penny. You can be rude, you can ignore her—she’s unshakable.

“Agatha,” she said, “do you honestly think I want to be with Simon?”

I think Penny wants to be the most important person in Simon’s life, so is that a yes or a no? “I don’t know, Penelope. But I know you didn’t want me to be with him.”

“Because you both seemed miserable!”

“That wasn’t any of your business!”

“Of course it was!” she said. “You’re my friends.”

I rolled my eyes at her, very obviously, but she kept going.

“This isn’t what I wanted to talk to you about,” she said briskly. “I heard Simon isn’t coming to your house for Christmas. And he can’t come to my house because my mum’s pissed off at the Mage, but I thought maybe you and I could still get together and make biscuits and exchange gifts.”

We always do this, every year, the three of us. “Without Simon?”

“Right, like I said, my mum’s got a bee in her bonnet about Simon.”

“But we never hang out without Simon,” I said.

“Only because he’s always around,” Penny said. “Just because you guys broke up doesn’t mean we’re not still friends, you and me.”

“We’re friends?”

“Nicks and Slick, I hope so,” Penny said. “I only have three friends. If we’re not friends, I’m down to two.”

* * *

“What’re you girls doing?” Penny’s mum comes into the kitchen, carrying her laptop, like she can’t put it down long enough to make herself a cup of tea. Her hair is pulled up in a messy dark bun, and she’s wearing the same cardigan and joggers she was wearing when I got here yesterday. My mother wouldn’t leave her bedroom looking like that.

Professor Bunce teaches History of the Middle Ages at a Normal university, and she’s a magickal historian. She’s published a whole shelf full of mage books, but she doesn’t make any money doing it. There aren’t enough magicians to support magickal arts and sciences as careers. My father does well as a magickal physician because he’s one of a few with the right training, and everyone needs a doctor. Penny’s dad used to teach linguistics at a local university, but now he works full-time for the Coven, researching the Humdrum. He even has his own staff of investigators who work in the lab with him upstairs. I’ve been here almost two days, and I haven’t seen him yet.

“He only comes out for tea and sandwiches,” Penny said when I asked her about it. She has a few younger siblings, too; I recognize them from Watford. There’s one camped out in the living room right now, watching three months’ worth of Eastenders—and at least one more upstairs attached to the Internet. They’re all frightfully independent. I don’t even think they have mealtimes. They just wander in and out of the kitchen for bowls of cereal and cheese toasties.

“We’re making gingerbread,” Penny says in answer to her mother. “For Simon.”

“Let it rest, Penelope,” her mum says, setting her laptop on the island and checking out our biscuits. “You’ll see Simon in a week or two—I’m sure he’ll still recognize you. Oh, Agatha, honestly, do the gingerbread girls have to be wearing pink?”

“I like pink,” I say.

“It’s good to see you girls spending time together,” she says. “It’s good to have a life that passes the Bechdel test.”

“Because our house is just teeming with your women friends,” Penny mutters.

“I don’t have friends,” her mum says. “I have colleagues. And children.” She picks up one of my pink gingerbread girls and takes a bite.

“Well, I’m not avoiding other girls,” Penny says. “I’m avoiding other people.”

“And I have plenty of girlfriends,” I say. “I wish I could go to school with them.” Not for the first time today, I think that I’m wasting a day with my real friends, my Normal friends, just to make nice with Penelope.

“Well, you’ll get to be with them next year, at uni,” her mum says to me. “What are you going to study, Agatha?”

I shrug. I don’t know yet. I shouldn’t have to know—I’m only 18. I’m not destined for anything. And my parents don’t treat me like I have to rise to greatness. If Penny doesn’t cure cancer and find the fairies, I think her mum will be vaguely disappointed.

Professor Bunce frowns. “Hmm. I’m sure you’ll sort it out.” The kettle clicks, and she pours her tea. “You girls want a fresh cup?” Penny holds hers out, and her mum takes mine, too. “I had girlfriends when I was your age; I had a best friend, Lucy.…” She laughs, like she’s remembering something. “We were thick as thieves.”

“Are you still friends?” I ask.

She sets our mugs down and looks up at me, like she’s only been half paying attention to our conversation until now. “I would be,” she said, “if she turned up. She left for America a few years after school. We didn’t really see each other after Watford, anyway.”

“Why not?” Penny asks.

“I didn’t like her boyfriend,” her mum says.

“Why?” Penny says. God, Penny’s parents must have heard that question a hundred thousand times by now.

“I thought he was too controlling.”

“Is that why she left for America?”

“I think she left when they broke up.” Professor Bunce looks like she’s deciding what to say next. “Actually … Lucy was dating the Mage.”

“The Mage had a girlfriend?” Penny asks.

“Well, we didn’t call him the Mage then,” her mum says. “We called him Davy.”

“The Mage had a girlfriend,” Penny says again, goggling. “And a name. Mum, I didn’t know you went to school with the Mage!”

Professor Bunce takes a gulp of tea and shrugs.

“What was he like?” Penny asks.

“The same as he is now,” her mum says. “But younger.”

“Was he handsome?” I ask.

She makes a face. “I don’t know—do you think he’s handsome now?”

“Ugh, no,” Penny says, at the same time as I say, “Yes.”

“He was handsome,” Professor Bunce admits, “and charismatic in his way. He had Lucy wrapped around his little finger. She thought he was a visionary.”

“Mum, you have to admit,” Penny says, “he really was a visionary.”

Professor Bunce makes a face again. “He always had to have everything his way, even back then. Everything was black-and-white with Davy, always. And if Lucy didn’t agree—well, Lucy always agreed. She lost herself in him.”

“Davy,” Penelope says. “So weird.”

“What was Lucy like?” I ask.

Penny’s mum smiles. “Brilliant. She was powerful.” Her eyes light up at that word. “And strong. She played rugby, I remember, with the boys. I had to mend her collarbone once out on the field—it was mad. She was a country girl, with broad shoulders and yellow hair, and she had the bluest eyes—”

Penny’s dad wanders into the kitchen.

“Dad!” Penny says. “Now can we talk?”

The other Professor Bunce fumbles towards the kettle and turns it on. Penny’s mum turns it off and takes it to the sink to add water, and he kisses her forehead. “Cheers, love.”

“Dad,” Penny says.

“Yeah…” He’s rummaging in the fridge. He’s a smallish man, shorter than Penny’s mum. With sandy blond-grey hair and a big squishy nose. He’s got unfashionable, round, wire-rimmed glasses tucked up on his head. Everyone in Penny’s family wears unfashionable glasses.

The gossip about Penny’s dad is that he’s not even half as powerful as her mum; my mum says he only got into Watford because his father used to teach there. Penny’s mum is such a power snob, it’s hard to imagine her married to a dud.

“Dad, remember? I needed to talk to you.”

He’s stacking food in his arms: Two yoghurts. An orange. A packet of prawn crackers. He grabs a gingerbread girl and notices me. “Oh, hello, Agatha.”

“Hello, Professor Bunce.”

“Martin,” he says, already leaving. “Call me Martin.”

“Dad.”

“Yeah, come on up, Penny—bring my tea, would you?”

She waits for his tea, then snatches a couple more gingerbread people—they’re eating them faster than I can decorate them—and follows him upstairs.

“Why did they break up?” I ask Professor Bunce after Penny and her dad have cleared out.

She’s staring at her laptop, holding her tea, forgotten, halfway up to her mouth. “Hmmm?”

“Lucy and Davy,” I say.

“Oh. I don’t know,” she says. “We’d lost touch by then. I imagine she finally realized he was a git and had to cross the ocean to get away from him. Can you imagine having the Mage for an ex? He’s everywhere.”

“How did you find out that she left?”

Professor Bunce looks sad. “Her mother told me.”

“I wonder why the Mage has never dated anyone else.…”

“Who knows,” she says, shaking it off and looking back at her computer. “Maybe he has secret Normal girlfriends.”

“Or maybe he really loved Lucy,” I say, “and never got over her.”

“Maybe,” Professor Bunce says. She’s not paying attention. She types for a few seconds, then looks up at me. “You just reminded me of something I haven’t thought of in years. Wait here.” She walks out of the kitchen, and I figure she probably won’t be back. The Bunces do that sometimes.

But she does come back, holding out a photograph. “Martin took this.”

It’s three Watford students, two girls and a boy, sitting in the grass—by the football pitch, I think. The girls are wearing trousers. (Mum says nobody wore school skirts in the ’90s.) One of them is pretty obviously Penelope’s mum. With her hair down and wild, she looks a lot like Penny. Same wide forehead. Same smirk. (I wish Penny were down here, so I could tease her about that.) And the boy is obviously the Mage—different with his hair longer and loose, and with no silly moustache. (The Mage has the worst moustache.)

But the girl in the middle is a stranger.

She’s lovely.

Shoulder-length yellow-blond hair, curly and thick. With rosy cheeks, and eyes so big and blue, you can see the colour in the photo. She’s smiling warmly, holding Penelope’s mum’s hand, and leaning into the boy, who has his arm around her.

The Mage really was dead handsome. Better looking than either of the girls. And he looks softer here than I’ve ever seen him, smiling out one side of his mouth, with an almost sheepish look in his eyes.

“Lucy and I never really fought,” Professor Bunce says. “I’d fight, and Lucy would just try to change the subject. It was never a fight at the end, either. I think she stopped talking to me because she got tired of defending Davy to me. He was so intense by the time we left school—radicalized, ready to charge the palace and set up a guillotine.”

I realize that Professor Bunce is talking to herself now, and to the photo, more than she is to me.

“And he never shut up,” she says, setting the photo on the counter. “I still don’t know how she could stand him.”

She looks up at me and narrows her eyes. “Agatha, I know I’m being indiscreet—but nothing we say in this kitchen leaves the kitchen, understood?”

“Oh, of course,” I say. “And don’t worry about it—my mother complains about the Mage, too.”

“She does?”

“He never comes to her parties, and when he does, he’s wearing his uniform, and it’s usually caked with mud, and then he leaves early. It gives her a migraine.”

Professor Bunce laughs.

Her mobile rings. She takes it out of her pocket. “This is Mitali.” She looks back at her computer and clicks at the touchpad. “Let me check.” She picks up the laptop, balancing it against her stomach, propping the phone between her ear and shoulder, and walks out of the room.

She leaves the photo on the counter. After a moment, I pick it up.

I look at the three of them again. They look so happy—it’s hard to believe none of them are on speaking terms now.

I look at Lucy, at the colour in her cheeks and her blue-sky eyes, and slip the photo into my pocket.