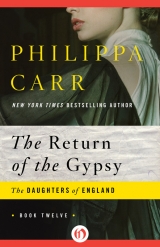

Текст книги "The Return of the Gypsy"

Автор книги: Philippa Carr

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

One of them came close to me and laid a hand on my thigh.

My father made an attempt to seize him but then Romany Jake spoke.

He said in loud tones which rang with authority: “Stop that. Leave the girl alone.”

The man who had touched me fell back.

There was silence, tense and ominous.

“Fools,” said Romany Jake. “Do you want to get the law on us?”

I was aware of the effect he had on the gypsies. The knife had been ready and was for my father. The man stood still with it in his hand.

“Get back,” said Romany Jake.

The man with the knife seemed to be some sort of leader. He said: “It’s time to show them, Jake.”

“Not now … not before the girl. Put that knife away, Jasper.”

The man looked at the knife and hesitated. It was a battle of wills, and I sensed that a great deal hung on this moment. Those watching people were ready to follow either man. Jasper wanted revenge, wanted to wreak his anger against those who owned land and whose permission had to be granted before the gypsies could rest their caravans. What Romany Jake felt on that subject I was not sure. He had spoken as though it were solely on my account that they were to hold off. What would have happened to my father if he had come alone?

My father remained calm. He said: “You seem a reasonable man. Be off my land by nightfall.”

Romany Jake nodded. Then he said quietly: “Go. Go now.”

“Come, Jessica,” said my father.

We turned our horses and walked them slowly away from the gypsy encampment.

When we had left the woods my father pulled up and turned to me. I saw that the rich colour which had suffused his cheeks while he was talking to the gypsies had receded and he was pale. There were beads of sweat on his forehead.

“That was a near thing,” he said.

“I was terrified.”

“And had every reason to be. And another time when I tell you to do something, I expect obedience.”

“What do you think would have happened if I hadn’t been there?”

“Ha! You may well ask. I would have given my full attention to those rogues.”

“Romany Jake saved us. You have to admit that.”

“He’s a rogue, like all of them. If they are not off by dawn tomorrow, there’ll be trouble for them.”

“That man with the knife …”

“Ready to use it, too.”

“And, Father, you had nothing.”

“I wish I had brought a gun with me.”

“I’m glad you didn’t. You had me instead, I was better than a gun.”

He laughed at me. I believed he was very touched because I had insisted on going with him.

“There’s no doubt whose daughter you are,” he said. “Jessica, forget I said this, but I’m proud of you.”

“I’m so glad I insisted on coming with you.”

“You think it would be the end of me if you hadn’t, don’t you? You’re kidding yourself. I’ve been in tighter spots. What beats me is that such a thing could happen on my land in broad daylight. Another thing … not a word of this to your mother.”

I nodded.

And as we rode home each of us was too emotionally stirred for words.

The next morning the gypsies left and there was lamentation in the kitchen because of the departure of Romany Jake.

The Verdict

LIFE SEEMED QUITE DULL after the gypsies had gone. We were all dismayed to hear of Napoleon’s great victory at Austerlitz that December. It seemed that he was not beaten yet. Trafalgar had merely robbed him of sea power and he was anxious to show that his armies were supreme.

However, we settled into the usual routine: lessons, rides, walks, visiting the sick of the neighbourhood with comforts. It was only with the preparations for Christmas that life became eventful again. Bringing in the log, hunting for mistletoe, cutting the holly, and all the baking that went on in the kitchens; selecting the gifts we were giving and speculating on what would be given to us: the usual happenings of the Christmas season.

Christmas came and went and it was January, three months after the gypsies had vacated our woods. I had not forgotten Romany Jake; I believed I never should. He had made a marked impression on me. I found myself thinking of him at odd moments. I was sure he had been attracted by me in a special sort of way; and there was no doubt that he had had an effect on me. He made me feel that I was no longer a child; and that there were many things I could learn and which he would teach me. I felt frustrated because he had gone before I could understand the meaning of this attraction between us.

The winds were blowing in from the north bringing snow with them. We had fires all over the house. I loved fires in the bedrooms; it was pleasant to lie in bed and watch the flames in the grate—blue flames which were due to the salty wood which was brought up from the beach after storms. It was great fun going down to collect it and to burn the pieces we had personally found; I always said that the pictures in the blue flames were more beautiful than any others.

Outside the wind buffeted the house; and there we were warm and cosy with our fires round which we sat roasting chestnuts and telling uncanny stories—the same which we told every year.

It was the middle of January, during an icy spell, when Dolly Mather came over to Eversleigh in a state of panic. She asked for young Mrs. Frenshaw. She seemed to have a special feeling for Claudine. I happened to come in just as Claudine was coming down to the hall, so I heard what was wrong.

“It’s my grandmother … Oh, Mrs. Frenshaw, she’s gone.”

“Gone!” For the moment I thought she was dead for people say “gone” because they fight shy of saying the word “dead” and try to make the act of dying less tragic by calling it something else.

Dolly went on: “She’s gone. I went to her room and she’s not there. She’s just gone …”

“Gone!” echoed Claudine. “How can she be? She found it hard to get about. Where could she have gone on a day like this? Tell me exactly …”

“I think she must have gone last night.”

“Oh no … Dolly, are you sure?”

“I’ve searched the house. She’s nowhere to be found.”

“It’s impossible. I’d better come over.”

“I’ll come too,” I said.

Claudine went up to her room to get her coat and snow boots. Dolly looked at me, staring in that disconcerting way she had.

“I don’t know where she can have gone,” she said.

“She can’t be far off. She was almost bedridden.”

Claudine came down and we walked over to Grasslands. There were only two servants there; the man who managed the small estate lived in a cottage half a mile away and his wife also helped in the house.

Dolly took us up to Mrs. Trent’s bedroom.

“The bed has not been slept in,” I said.

“No. She couldn’t have gone to bed last night.”

“She must be in the house somewhere.”

Dolly shook her head. “She’s not. We’ve looked everywhere.”

Claudine went to the cupboard and opened the door. “Has she taken a coat?” she asked.

Dolly nodded. Yes, she had taken a coat.

“Then she must have gone out.”

“On a night like last?” asked Dolly. “She would have caught her death.”

“We’ve got to find her,” said Claudine. “She must have had some sort of breakdown. But where could she have gone?”

Dolly shook her head.

“I’ll go back to Eversleigh,” said Claudine. “We’ll send some men out to look for her. It’s going to snow later on. Where on earth can she be? Don’t worry, Dolly. We’ll find her. You stay here. Get a fire going in her bedroom. She may need to be warmed up when she gets back.”

“But where is she?” cried Dolly.

“That’s what we have to find out. Come along, Jessica.”

As we trudged back to Eversleigh, Claudine said: “What a strange thing … That old woman. She had difficulty in walking up and down the stairs. I can’t think what this means. Oh dear, I do hope she is all right. I can’t think what will become of Dolly if anything happened to Mrs. Trent.”

“It’s Dolly who really cared for Mrs. Trent.”

“But Dolly … all alone in the world.”

“She can’t be far away,” I said.

“No. They’ll soon find her. But if she has been out all night … in this weather …”

“She must have sheltered somewhere.”

As soon as we returned to Eversleigh and told them what had happened search parties were organized. As predicted it started to snow and the strong winds were making almost a blizzard. The search went on all through the morning, and it was not until late afternoon when Mrs. Trent was found, not by one of the searchers, but by Polly Crypton. Polly had been out—bad as the weather was—to take a potion to old Mrs. Grimes, in one of the cottages, who suffered terribly from rheumatism and had run out of her medicine. Coming back Polly had stumbled over something close to her garden gate. To her horror she had discovered that it was a woman, and looking closer had recognized Mrs. Trent.

It was clear to Polly that she had been dead some time. She hurried to give the alarm, and at last Mrs. Trent was brought back to Grasslands.

Several of us were there—my mother, Claudine, David, Amaryllis and myself. The doctor had come. He said that the effort of walking so far would have put a great strain on her impaired health; it was his opinion that exhaustion had been the main cause of her death; and even if that had not been the case she would have frozen to death.

“Whatever possessed her to go out in such weather?” cried Claudine.

“She must have been temporarily out of her mind,” said my mother.

“It is Dolly who worries me,” went on Claudine. “We shall have to take special care of her.”

Poor Dolly! She was like one in a dream. She spent a great deal of time at Enderby where she was warmly welcomed by Aunt Sophie—herself the victim of misfortune, she was always ready to show sympathy to those whom life had treated ill.

The day of the funeral came. Claudine arranged it all. Dolly had listlessly stood aside and accepted help. We all attended the church and followed the coffin to the grave. Poor Dolly, chief mourner, she looked so frail and white; and at times of emotion that deformity in her face seemed more prominent. Even Aunt Sophie attended in deep black with a black chiffon hood hiding half of her face; she looked very strange standing there at the grave like some big black bird, a prophet of doom. But Dolly kept close to her and clearly drew more comfort from her than from Claudine who was doing so much to help.

Claudine had insisted that the funeral party come back to Eversleigh, so there they all were, talking about Mrs. Trent and how well she had cared for her grand-daughter, and how well she had managed Grasslands, not an easy job for a woman even though she had a good manager. We remembered all the pleasant things about Mrs. Trent as people always do at funerals. I had heard people say—when she was living—that she was an old witch and that if she had been different, her grand-daughter Evie would never have committed suicide when she found herself pregnant, and that poor Dolly had a “life of it” looking after her. But she was dead and death wipes away a person’s faults and gives virtue in their place.

But Mrs. Trent’s virtues were discussed with not so much fervour as was the reason for her sudden departure from the comforts of Grasslands to go out into the bitterly cold winter’s night.

Claudine said that Dolly must stay at Eversleigh for a few days, but Aunt Sophie insisted that she go to Enderby; and it was clear that this was Dolly’s preference. So Dolly stayed with Aunt Sophie for a week after the funeral and then she returned to Grasslands. Claudine said that we must all keep an eye on her and do what we could to help her over this terrible tragedy.

One day when Claudine returned home from visiting Aunt Sophie, she looked very grave and I saw from her expression that something had happened. She went straight to my mother and they were closeted together for a long time.

“Something is going on,” I said to Amaryllis and she agreed with me.

“I’m going to find out,” I added. “It’s something about Aunt Sophie because it is since your mother came back from there that it started.”

I made a few tentative enquiries in the kitchens but I could glean nothing there so I decided to ask my mother.

I had always been treated in a rather special way by my mother. It may have been that she was older than most mothers are when their children are born, and she did tend to treat me more as an adult than Claudine and David did Amaryllis. It may have been that I was more anxious to be regarded so than Amaryllis. “Pushing,” as some of the servants called it.

So when I found my mother in one of what I called her dreamy moods, I asked her outright if there was something going on, some secret adult matter which was considered to be not for the ears of the young.

She looked at me and smiled. “So you have noticed,” she said. “My goodness, Jessica, you are like a detective. You notice everything.”

“This is rather obvious. Claudine went to Aunt Sophie and came back, well… secretive … anxious and strange.”

“Yes, there is something, but it is not Aunt Sophie. You will have to know in due course, so why not now?”

“Yes, you might as well tell me,” I agreed eagerly.

“It’s Dolly. She is going to have a baby.”

“But she is not married!”

“People occasionally have babies when they are not married.”

“You mean …”

“That is what is troubling us. Dolly herself is happy enough, almost ecstatic. That’s a help in a way but it is more unfortunate. Your Aunt Sophie will help all she can. We shall all have to be gentle with Dolly. She has had a very hard life. She adored her sister who drowned herself because of her own pregnancy. So now you see why we are worried about Dolly.”

“You don’t think Dolly will kill herself?”

“On the contrary. She seems delighted at the prospect.”

“ ‘My soul doth magnify the Lord’… and all that,” I quoted irreverently.

My mother looked at me intently. “Perhaps I shouldn’t be telling you all this. Sometimes, Jessica, I forget how young you are.”

“I’m quite knowledgeable. One learns about these things. I knew about Jane Abbey’s baby before she had it.”

“Your father thinks you are wise beyond your years.”

“Does he?”

“But most parents think there is something special about their offspring.”

“But my father is not like most parents. He would only think it if it were so.”

She laughed and ruffled my hair. “Don’t say too much about Dolly, will you? Not just yet. Of course it will come out and there’ll be a lot of gossip. But don’t set it going.”

“Of course not. I’ll only tell Amaryllis; and she never talks about anything if you tell her not to.”

I went away and thought a good deal about Dolly. Oddly enough I was to talk to her soon after my conversation with my mother.

I went over one day to see Aunt Sophie. Jeanne told me she was sleeping so I went into the garden to wait for a while and whom should I see there but Dolly.

She looked different. There was no thickening of her figure yet but there was a certain transformation in her face. The drawn-down eye was less noticeable. There was a little colour in her cheeks and the visible eye shone with a certain delight and, yes … defiance.

She was more talkative than I had ever known her.

I did not, of course, refer to the subject. It was she who brought it up.

“I suppose you know about me?”

I admitted I did.

“I’m glad,” she said. She gave me that odd look. “In a way you’re to blame.”

“I? What have I done?”

“When you were a little baby I kidnapped you. Did you know that?”

“Yes,” I said.

“I thought you were the other one. I was going to kill her.”

“Kill Amaryllis! Whatever for?”

“Because she was alive … and oh … it’s an old story. But my sister had lost her lover and she killed herself. It was all mixed up with them at Eversleigh. It was their fault that it had happened. She was going away with her lover and I was going with her to look after the little baby.”

“You mean … you wanted revenge through Amaryllis?”

“Something like that.”

“But Amaryllis … she is the most inoffensive person I ever knew. She would never do anyone any harm.”

“It was because she was a baby and I’d lost Evie’s. But I took you instead … the wrong baby, you see. I had you up in my room hidden away. I was afraid you were going to cry. You were the most lovely baby I had ever seen. I used to try to make myself believe you were Evie’s baby. You used to smile at me when I spoke to you. I just loved you when you were a baby. That was when above everything I wanted a baby of my own. It was you who started it. And now I’m going to have one.”

“You seem very happy about it.”

“I always wanted a little baby… ever since I took you. I thought I’d look after Evie’s. I don’t care what people say. It will be worth it to have a little baby. You’d like to know about it, wouldn’t you?”

I did not speak for a moment. I looked into her face and I thought of her dancing round the bonfire on Trafalgar night.

“And … the baby’s father?” I said weakly.

She smiled, reminiscently, I thought.

I said: “Was it… Romany Jake?”

She did not deny it. “He used to sing those songs for me. No one ever cared about me before. He said life was meant for enjoying. There should be laughter and pleasure. ‘Live for today,’ he said, ‘and let tomorrow take care of itself.’ The gypsies lived a life of freedom. It was what they cared about more than anything. And so … I was happy … for the first time in my life, really. And now… there is going to be a little baby … mine and Jake’s.”

I felt deflated; betrayed. I could see him so clearly standing there in the light of the bonfire. I had felt he was calling to me … to me … not to Dolly. He had wanted me to be down there dancing with him and I had wanted to be there. Only now did I realize how much.

“Dolly,” I said, “did he ask you to go off with the gypsies … with him … ?”

She shook her head.

“It was such a night… It was the people dancing and singing … and everything somehow not quite real. I’ve never known anyone like him.”

“You will love the baby, Dolly.”

Her smile was ecstatic. “More than anything on earth I wanted a little baby … a little baby of my own,” she repeated.

I thought what a strange girl she was! She had changed, grown up suddenly. Though she was adult in years, there had always been a childishness about her, perhaps because she was so vulnerable. I was angry suddenly with Romany Jake. He had taken advantage of her innocence. He had called to me with his eyes, with his presence … but I was too young … I was guarded by my family and so he had turned to Dolly. It was wrong; it was wicked … but it had given Dolly what she wanted more than anything on earth.

She said: “I have nightmares about Granny. You know how you feel when it’s your fault… in a way. I could say I killed her.”

“You!”

“I didn’t know where she had gone … not then. But now I know and I know why. There was a terrible scene that night before she died. I’ve got to tell someone so I’ll tell you because it was partly your fault for being the baby you were … and it was your family who made Evie do what she did. But for the Frenshaws at Eversleigh, Evie’s lover would never have been found out and he would have gone to France with Evie and me and she would have had the dear little baby … so it was the Frenshaws’ fault in a way.”

“Tell me what happened that night when your grandmother went out in the cold.”

“She thought there was something wrong with me and she questioned me. When I said I was going to have a baby she nearly went mad with rage. She kept saying, ‘The two of you. It’s happened to the two of you. What’s wrong with you …’ That seemed to upset her so much that it took her right back to the time when Evie had died. She always thought afterwards that if she had been different Evie would have come to her with her trouble and something could have been sorted out. She blamed herself and that was why she was so ill. She kept shouting, ‘Who was it?’ and when I told her she cried out, ‘The gypsy! God help us, I can’t bear this. You … and the gypsy …’ I told her that he was a wonderful man and that there was no one I’d rather have for the father of my child, and the more I talked the more mad she became. She kept saying she had failed with us. She had planned for us; she had wanted so much for us … and I was going the same way as Evie. She kept on and on about Evie. I thought she really had gone mad. I didn’t know she had left the house. She told me to leave her alone and I did. ‘Go away,’ she said. ‘I’ve got something to do. Go away and leave me in peace to do it.’ She was so upset I went out and left her and in the morning she had gone. I know now where she had gone. She was making her way to Polly Crypton. Polly knows what to do to get rid of babies. She had done it before for girls in trouble. That was where my grandmother was going on that night. She was going to Polly Crypton to get her to do something to destroy my child.”

“Oh, Dolly, what a terrible story! Poor Mrs. Trent, she cared so much for you.”

“It was the wrong sort of caring … with Evie and with me. Evie was afraid to tell her. I shall never forget the day she learned that her lover was dead and we shouldn’t be going away with him after all. She kept saying, ‘What shall I do?’ I said we’d tell Granny and we’d stand together and we’d manage somehow. But, you see, she could not bring herself to tell Granny. She chose to drown in the river instead. Granny blamed herself for that, and when she knew that I was going to have a child it brought it all back to her. She was going to stand by me. That was why she went to Polly Crypton’s on that night.”

“I’m so sorry, Dolly. You know we’ll do everything … everything we possibly can.”

“Yes. Madame Sophie wants to help me. So do the two Mrs. Frenshaws. I’ll be all right.”

Jeanne was calling that Aunt Sophie was ready to see me. I touched Dolly’s hand gently and as I ran into the house I was still seeing Romany Jake standing there in the light of the bonfire and wondering what would have happened … if I had danced with him as Dolly had done.

By the time spring came, people ceased to talk much about Dolly and her coming child. No one seemed to think very harshly of her. I suppose it is only when people envy others that they revel in their misfortunes. Nobody ever envied Dolly. “Poor Dolly,” they all said, even the most humble of them. So if she had had her hour of abandoned passion and this was the result—about which she was delighted—who was to grudge her that?

She spent a great deal of time at Enderby. Aunt Sophie was quite excited at the prospect of the coming child. Jeanne Fougere made all sorts of nourishing dishes, and Dolly seemed to like to be cossetted. Aunt Sophie said that when the time came she must go to Enderby. The midwife should be there and Jeanne would look after her. My mother commented that she had rarely seen Sophie so happy.

Soon it was summer. The war with France dragged on. One grew used to it and a little bored by it. It seemed there was always war with France and always would be.

It was the end of June. Dolly’s baby was expected in July. Aunt Sophie insisted that Dolly leave Grasslands and take up her residence at Enderby and Dolly seemed happy to do so. She was completely absorbed in the coming baby and it was wonderful to see her so contented. For as long as I could remember she had been mourning her sister Evie and had been very much her grandmother’s prisoner. Now she was free and that which she wanted more than anything—a child of her own—was about to come to her.

“It’s a strange state of affairs,” said my mother. “That poor girl with her illegitimate child … the child of a wandering gypsy… and there she is for the first time in her life really happy.”

“Yes,” added Claudine, “even in the days when Evie was alive, she was overshadowed by her. Now she is a person in her own right… about to be a mother, no less.”

“I do hope all goes well for her,” said my mother fervently.

Jeanne had taken one of the cradles from the Eversleigh nursery and had made flounces of oyster-coloured silk for it. It was a glorious affair by the time Jeanne had finished with it. There was a room at Enderby called “the nursery”; and Aunt Sophie talked of little else but the baby. Jeanne was making baby clothes—very beautiful ones at that—and Aunt Sophie embroidered them.

It certainly was an extraordinary state of affairs, as my mother said.

The few servants who had been at Grasslands resided chiefly at Enderby now, going to Grasslands only a few times a week to be sure the place was kept in order.

When I walked past it I thought it had a dead look. It would soon have the reputation Enderby used to have. David had said that a house acquired a ghostly reputation because the shrubs were allowed to enshroud it, giving it a dark and sinister appearance. It was not the houses themselves which were haunted; it was the reputation they were given, and people usually saw to it that those reputations were enhanced. Things happened in supposedly haunted houses because people imagined they would.

With July the weather came in hot and sultry. Late one afternoon I had been over to Aunt Sophie with a special cake our cook had made and to enquire after Dolly’s health. When I came out of the house I noticed the heavy clouds overhead.

One of the servants called to me: “You’d best wait awhile, Miss Jessica. It’s going to pelt down in a moment or two. There’s thunder in the air, too.”

“I’ll be at Eversleigh before it starts,” I replied.

And I set out.

There was a stillness in the air. I found it rather exciting. The calm before the storm! Not a breath of wind to stir the leaves of the trees … just that silence, rather eerie … ominous in fact. It was the kind of silence in which one could expect anything to happen.

I walked on quickly. I was near Grasslands. I glanced at the house … empty now. I stood for a few seconds looking up at the windows. Some houses seem to have a life of their own. Enderby certainly had. And now… Grasslands. Eversleigh? Well, there were always so many people at Eversleigh. Enderby had had an evil reputation before Aunt Sophie had gone there, and a woman whose face was half hidden from sight because of a dire accident could hardly be expected to disperse that. Grasslands? Well, people had said that old Mrs. Trent was a witch; and her grand-daughter had committed suicide and now the other was going to have an illegitimate child. It was stories like that which made houses seem strange … influencing the lives of the people who lived in them.

There was a faint rumbling in the distance and forked lightning shot across the sky. Several large drops of rain fell on my upturned face. The black clouds overhead were about to burst.

I was flimsily clad. I ought to take shelter. The rain would pelt down but it would very likely soon be over. I looked about me. “Never shelter under trees in a thunderstorm,” my mother had often warned me.

I turned in at the gate. I could find adequate shelter under the porch at Grasslands.

I started to run towards the house; the rain was coming down in earnest now. I looked up. Then I stopped short for there at one of the upper windows, I saw … or thought I saw … a face.

Who could be there? Dolly was at Enderby, so were all the servants. There were only three of them and I had seen them all that afternoon.

A dark face … I could not see clearly. It had moved swiftly away as I looked up. Was it a trick of the unusual light? A fancy? But I was sure I saw the curtains move.

I reached the porch and stood there. I was quite wet already. Who could be in the house? I wondered.

One of the servants? But I had seen them all at Enderby just before I left. I pulled on the somewhat rusty chain and the bell rang. I could hear it echoing through the house.

“Is anyone at home?” I called through the keyhole.

There was no answer—only a loud clap of thunder.

I rapped on the door. Nothing happened. It was a heavy oak door and I leaned against it, feeling that something very strange was happening. I am not particularly scared by thunderstorms, especially when other people are there, but to see that lightning streaking across the sky and to wait for the violent claps of thunder which followed and to watch the rain violently hitting the ground when behind me was a house which should have been empty … well, I did feel a strange sort of fear which made my skin creep.

I stood for a while watching the storm as it grew wilder. My impulse was to run, for suddenly I knew that there was someone on the other side of the door.

“Who is there?” I called.

There was no answer. Did I hear heavy breathing? How could I? The storm was too noisy, the door too thick.

What was it I was aware of? A presence?

I would brave the storm. They would scold me. Miss Rennie would say, How foolish to run through it. You should have stayed at Enderby till at least the worst was over …

I shivered. My thin damp dress was clinging to me, but I was not really cold. It was just the thought that there was someone in that house who was aware of me … and that it was very lonely here.

I turned to the door and put my hands against it. To my amazement it opened.

How could that be? It had been shut. I had leaned against it. I had rapped on it and now… it was open.

I stepped into the hall.

It was dark because of the weather. I looked up at the vaulted ceiling which was rather like ours at Eversleigh but smaller.

“Is anyone there?” I called.

There was no answer and I had the feeling that I was being watched.

I advanced cautiously, crossing the hall to the staircase. I heard a movement and hastily turned round. There was no one in the hall. The door swung shut with a bang. I ran over to it. Someone was in the house and I had to get out quickly. I had to run home as fast as I could, never mind the storm.

A figure appeared at the top of the stairs. I stared.

“Are you alone?” said a voice.

“It’s … it’s …” I stammered.

“That is right,” he said. “You remember me.”

“Romany Jake,” I murmured.

“And the lady Jessica.”

“What are you doing here?”

“I’ll tell you. But first are you alone … Is anyone with you? Anyone coming after you?”

I shook my head. I was no longer afraid. Waves of relief were sweeping over me. I could not feel afraid of Romany Jake—only a tremendous excitement.

He came down the stairs stealthily.

“It was you who were behind the door. You were at the window … You opened the door so that I would come in. What are you doing here?”