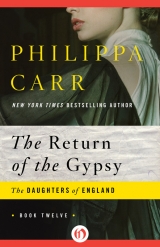

Текст книги "The Return of the Gypsy"

Автор книги: Philippa Carr

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 22 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

I could see Clare’s point of view and why her antagonism was aroused against me.

I was glad when it was midnight and I told my mother we must leave. We had to get Edward home and for that reason we had the carriage, so we would all go home in it with Edward: Jake, Clare, myself and Tamarisk who had been allowed to sit up as it was Christmas.

Toby came too for he was needed to help Edward into the carriage. James was still suffering from his strained back and Toby was very useful.

We said goodnight to my mother and other guests and set out for home.

“What a wonderful Christmas Day it has been!” said Jake. “There is nothing like the old traditions.”

We all agreed and Edward told us about Christmases in Nottingham and we all joined in until we arrived at Grasslands.

Toby—with Jake’s help—took Edward to his room; Clare said goodnight and took a somewhat subdued Tamarisk off with her. She would soon be asleep. Indeed she was halfway to that state already.

I met Jake coming out of Edward’s room. “All is well,” he said. “That Toby is a strong young man.”

“Goodnight, Jake.”

He took my hand and kissed it. “Come with me,” he whispered.

I shook my head.

“Just see me up and say goodnight.”

I went up the stairs with him to the bedroom. It looked very cosy. There was a fire in the grate and it threw its flickering light on the red curtains which had been drawn across the windows.

He closed the door and put his arms round me. “Stay with me,” he said.

“No. I am going to sit with Edward. I always do when they have got him to bed.”

“Afterwards … come back.”

“No, Jake. Not here.”

“Does it matter where?”

“Yes, I think so.”

“What strange ideas you have, Jessica. Place and time … they are unimportant. What matters is that we are together.”

“Edward is so near.”

He looked at me in tender exasperation. “You will stay with me here … through the night… please.”

“I couldn’t. It would seem to me as though Edward were here… in this room. It would seem like the ultimate betrayal.”

“If you are going to think along those lines the ultimate betrayal has already taken place.”

“I don’t think you see it as I do. Perhaps infidelity comes more naturally to men. It is condoned by society … unless it is discovered. What I have done is so wrong. It would be wrong for any woman … but because of Edward it is dastardly. I hate myself.”

“For loving and being loved by me?”

“Oh no … not for that. That is something which will always sustain me. I shall always love you, Jake. But I have made up my mind very definitely that I cannot leave Edward. I shall be with him as long as he needs me. I have given him my word and that is how it shall be. He has suffered so much. I would never add to that suffering if I could help it.”

“Do you mean that I must go away … I must leave you … that all I have to hope for is the snatched moment?”

“You will go away knowing that I love you as you love me.”

“I love you exclusively. I would never allow anything to stand in my way. I should consider no one but you… us … being together always.”

“You have seen how it is.”

“I have seen, of course, that Edward relies on you. He would be very sad if you went away. But he is not a man who would demand a sacrifice.”

“He is the most unselfish of men.”

“Yes. He has qualities which I do not possess. Yet you love me, remember. You loved me enough to break those marriage vows by which you set such store.”

“I do. I do. But you must understand. I must be here. I must stay with Edward while he needs me. I married him. I must remember that. It is too late for us, Jake.”

“It is never too late.”

And now, I thought, someone knows about us. Someone took the letters you wrote to me. Clare? Leah? I wanted to tell him to make him understand how careful we must be. But I hesitated. He would brush it aside. It was unimportant, he would say. Some day everyone would know that we were lovers because he did not intend to allow matters to remain as they were.

I withdrew myself.

“I must go and sit a while with Edward. I always chat with him for a few minutes before I say goodnight. He looks forward to it.”

“Come back,” he said.

I did not answer but came out of the room, and as I did I heard a door quietly shut. It could have been Clare’s room or that of Tamarisk. Tamarisk was adept at listening at doors. I thought Clare might not be guiltless either.

I went down to Edward’s room. He was in bed waiting for me. And his face lit up with pleasure as I came in.

I sat down beside the bed. On the top of the small cabinet which served as a table was the sleeping draught he took most nights, for he often found it difficult to sleep and the doctor said he must get the rest he needed.

On this night he looked tired. It had been a strenuous day for him.

I said: “You must be tired. It has been a heavy day.”

“Christmas is rather special, isn’t it?”

“Did you enjoy it?”

“Very much. Has our guest retired?”

“Oh yes. He’s probably fast asleep by now.”

“So should you be.”

“I shall go after our chat.”

“I loved to see you dancing. How I wish …”

I sighed and he went on: “Sorry, self pity.”

“You’re entitled to a little. Heaven knows you don’t indulge in it often.”

“I should not be sorry for myself… having you.”

I kissed him.

“Sleep well,” I said.

“I’m not really tired. It must be the excitement of Christmas.”

“So you will have your draught tonight?”

“Yes. I asked James to leave it ready for me. It’s effective.”

I picked up the glass and gave it to him.

He drank it and grimaced.

“Unpleasant?”

“A little bitter.”

“Well, I shall say goodnight.” I stooped over and kissed him. He returned my kiss lingeringly.

“God bless you, dearest Jessica, for all you have given me.”

“God bless you, Edward, for all you have given me.”

He smiled at me ironically and I shook my head at him.

“Always remember, Jessica, I want to do what is best for you.”

I kissed him hurriedly once more and went out of the room. I felt as I always did when he revealed his devotion to me … unclean and ashamed.

I came up the stairs. The door of Jake’s room was slightly open. I stood still for a few seconds looking at it. Then I took a step towards it.

I hesitated. I had a feeling I was being watched.

I turned away and went deliberately to my own room. I shut the door firmly, all the time fighting the urge to go to him to give way to my longing, to abandon the principles to which I was trying so desperately to cling.

I went to bed, but not to sleep. I lay awake for a long time thinking of Jake in his room, waiting for me in vain.

It was symbolic of the future.

I must never go to him. I must give my life to looking after Edward. I felt very apprehensive, waiting, fearful that Jake would come to me, for if he did I knew I should have no power to resist.

Finally I slept.

I was awakened early next morning by a knocking on my door.

I called: “Come in.” It was Jenny, one of the maids. She looked white-faced, disbelieving and scared.

“What’s wrong?” I asked, starting up.

“Oh, Madam, will you come … at once. It’s the master. James said to tell you he wanted to see you.”

“Where is he?”

“In the master’s bedroom.”

I leaped out of bed snatching my dressing gown. I ran downstairs to Edward’s room. He was lying back in bed, unnaturally white and very still.

I felt myself turn cold and I started to shiver.

I murmured: “Oh God, please don’t let it be …” I went to the bed and took his hand. It was cold and fell limply from my grasp.

“James?” I cried.

James came to me and shook his head. “I’m afraid …” he began.

I murmured: “Dead. Oh no, James … not dead.”

“I’ve sent Toby for the doctor.”

“When … ?”

“I came in this morning to see about breakfast as usual. I did not notice at first. I drew back the curtains and said good morning. There was no answer. Then I came to the bed and I saw … I couldn’t believe it. Then I sent Jenny for you.”

“James … how… ?”

James looked at the glass which was on the top of the cabinet—the very one which I had handed to Edward on the previous night.

“Oh … no,” I said.

“We won’t know until the doctor comes.”

“But there was nothing wrong with him … apart from his injuries … nothing that would be fatal?”

James shook his head. “Sit down, Mrs. Barrington. You look faint.”

“It can’t have been …” I went on.

“He was worried about himself… being so incapacitated. We’ll have to see what the doctor says.”

Clare came running in. “What is it? They are saying …”

She looked from Edward to me. “Oh no. It can’t be true …” Her eyes came to rest on me. They were dark with misery and suspicion.

“How I wish the doctor would come,” I said.

There was a terrible silence in that room. The tick of the clock seemed unusually loud. I thought: I’m dreaming. This can’t be. Edward … dead!

At last the doctor was with us. We left him alone with Edward and when he came out he was very grave.

“Mrs. Barrington,” he said, “this is most distressing.”

“I cannot believe it,” I said. “Why … Doctor … what…”

“I am certain it is the sleeping dose. How much did he take?”

“James always prepares it for him.”

James said quickly: “It was the usual dose, doctor.”

“I think it was more than that last night.”

“So it was that,” I murmured.

I thought of our last meeting when I had sat by his bed and he had kissed the eternity ring. He had wanted the best for me. A horrible thought struck me. Had he deliberately taken that dose … to make me free? Oh no, he would not do that. I had never allowed him to think for a moment that I wanted to be free. But did he know?

Clare was looking at me with horror in her eyes.

The doctor said: “Was the bottle within his grasp?”

I knew that question was fraught with meaning. Had Edward taken the strong dose himself or had it been given to him?

James hesitated. “It was in the cupboard beside his bed. I suppose he could just have managed to get the door open and take out the bottle.”

The doctor nodded. “There will have to be an autopsy, of course.”

A terrible fear had started to race round and round in my mind. I was trying to remember all that had happened last night. Jake had helped Toby carry Edward in. The glass had been beside his bed when I entered the room. I had actually given it to him.

How much of the drug had been dissolved in that water? One small dose was all that must be taken. It was dangerous to take more. That was clearly stated and the doctor had warned us many times that more than the prescribed dose could be fatal.

Jake had been there. He had helped Toby to bring Edward in. He had killed a man once and he had said only this night: “I will find a way.”

I was desperately afraid.

The doctor had just left and we were seated together in the drawing room—myself, Clare and Jake with James. A terrible silence had fallen on us. I dared not look at Clare; I could see the accusation in her eyes. I dared not look at Jake. I was terribly afraid of what I might read in his eyes.

At length James spoke: “How could it have happened? I did not think he would ever attempt it. He was a man who believed that life had to be lived to the end no matter what tribulations had to be faced. It would have been all against his nature … as I knew it.”

Jake said: “Where was the stuff? Could he have reached it?”

“Yes … just,” said James. “The little cabinet served as a table. It wouldn’t have been easy for him to reach the bottle but he could have done so.”

“He would never have done it,” burst out Clare. “I know he would never have done it.”

“What alternative is there?” asked Jake in a curiously quiet voice.

There was silence and I felt Clare’s eyes on me accusingly. I raised mine and looked at Jake. For a few moments his gaze held mine. I did not know what I read there. But the thought would come to me. He killed a man once. He had done that in the heat of anger. If one had killed once did it come easily to do it a second time?

No, I thought. Not that. There had been a barrier between us before. That would be an insurmountable one. I must know the truth. I should not have a moment’s peace until I did.

I heard myself saying: “What actually happened last night? When could it have been put in the glass? Was Edward alone for any time?”

James said: “Sir Jake and Toby helped him out of the chair. We got him into bed between us. I poured out the water and put in the sleeping draught. I put it on top of the cabinet. We talked as we always did. He was in good spirits but of course he always did hide his feelings. What happened then? I think we all went out.”

“I believe I lingered to say a few words to him,” said Jake.

My heart began to beat very fast. Oh, Jake, I thought, were you alone with him … even for a few minutes?

“Well, Mr. Barrington was by himself until you came in, Mrs. Barrington.”

“Had he taken the sleeping draught then?” asked Jake.

“No. He usually took it while I was there… just as I was leaving actually. He didn’t want to feel sleepy while we were talking. I stayed a while. We talked as usual. He drank it while I was there. Then I took the glass from him and put it on top of the cabinet.”

“I can’t understand it,” said James. “And on Christmas night! If he had contemplated doing it he would surely not have chosen Christmas night.”

“You think the time is important?” said Clare harshly.

“Well,” explained James, “he would think of people enjoying Christmas. He was always one to think of other people. No. It was a mistake. He would never have killed himself in the first place … and certainly not on Christmas night.”

“Then,” said Clare, and I noticed how her eyes glittered, “someone else must have done it.”

There was silence with none of us daring to look at each other.

Suddenly I knew I could endure no more. I stood up and said: “There will be things to do.” And I went out of the room.

I cannot remember much of the rest of that day, except that it was like a bad dream. Messages were sent to Mr. and Mrs. Barrington. My father and mother came to Grasslands. They were deeply shocked. Amaryllis came over with Peter.

Amaryllis was deeply moved; she embraced me with great affection. “Dear, dear Jessica, this is terrible. Poor Edward! But it is those who are left who suffer. He was such a good man, and he loved you so much.”

I knew that whatever happened I would always have Amaryllis’ support and affection. I noticed Peter watching me rather sardonically. I dared not think what was going on in his mind.

My mother said: “Would you like to come back with us to Eversleigh? Your father says you are not to worry. He is going to take charge of everything. There’ll have to be an inquest. Perhaps it would be better for you to stay with us until that is over.”

I said I would stay at Grasslands.

“What about Tamarisk? Perhaps I’ll take her back with me. Jonathan can come over and persuade her if she is difficult.”

“Yes,” I said. “I should be glad of that. It is no place for her.”

“I expect the Barringtons will be here soon. What a terrible blow to them! They are such a devoted family and Edward was the apple of their eyes … particularly I think since his infirmity.”

The long day dragged into evening and I was glad when it was time to retire. I had avoided Jake all day. There was so much I wanted to say to him and so much I was afraid to say. I thought that if I asked him outright he would tell me the truth.

But did I want to know the truth? In my heart I was terrified of it.

I went to bed but I knew I should not sleep. I lay there, my eyes shut, thinking of the previous night and trying to recall every second, what Edward had said, what I had said. Had he seemed different? I was trying to read something in his words, something significant. I was trying to make myself believe that there was a possibility that Edward had taken his own life. If he had, then it was what he wished. I remembered how he had persuaded me to dance with Jake. I had looked over my shoulder and seen his eyes following me wistfully.

If Edward had taken his life it must have been what he wished. He had a right to leave this world if it had become intolerable to him. But no one else had a right to banish him from it. Only if I could be sure that Edward had wished to die and had taken the action himself, could I begin to grow away from the tragedy. No one … not even Jake … could make me truly happy again if that were not so.

How could I know?

The door of my bedroom opened quietly. For a moment I thought it was Jake and sat up ready to protest. It was not Jake. It was Clare.

She stood at the end of my bed. “Edward is dead,” she said, as though I did not know it. “He had to die, didn’t he? Otherwise how could you marry your lover?”

“What are you saying?”

“Surely you know. I loved Edward as you could never love anyone. When I came to them I was only seven years old, the poor relation. Oh, they were kind, but he gave me a special sort of kindness. He made me feel as though I were a person … not just a poor relation taken in because I had nowhere else to go. He was different. He was fond of me. I believe he would have been very fond of me. But you had to come along and spoil it.”

“I’m sorry, Clare.”

“Sorry? I don’t suppose you ever thought of him… or me … or anyone but yourself. You wouldn’t have him for a long time and then you decided you would. After that you made the grand gesture, didn’t you? He was crippled. He would never walk again, so you would show everyone how noble you were.”

“It wasn’t like that.”

“I know how it was. You thought Peter Lansdon wanted you. You thought every man must want you. And when he turned to Amaryllis it was a great shock, so you thought, All right, I’ll take Edward. So you did. That was why you became engaged to him. And then you got tired of it, didn’t you? I would have given my whole life to nursing him. But you took a lover, didn’t you … the dashing Sir Jake.”

“You don’t understand, Clare.”

“I understand everything. Do you think I am blind? I know what is going on. And I have proof.”

I stared at her and she laughed at me. “It’s all rather clear. He set it down, didn’t he? I have two letters he wrote to you. Don’t think you are going to brush me aside again. It’s evidence, you know. I will show them the letters. You were both with him that night. Sir Jake was there. Did he put in the extra dose or did you? Perhaps when you went in to say goodnight to him? You actually handed it to him, didn’t you? You said you did. Which one put in the fatal dose is anyone’s guess. But it was you who handed it to him.”

“Clare, Clare, what are you saying?”

“That you and your lover between you killed Edward.”

“It’s not true. I wouldn’t have hurt him for …”

“Wouldn’t you? When you had your lover staying in this very house?”

“There is so much that you don’t know.”

“And so much I do, eh? Don’t imagine I shall stand by and let you get away with this. I am going to show them at the inquest. I am going to give them proof.”

“It is no proof.”

“It is proof that two people in this house wanted Edward dead, and both of those people were with him on the night. They both had an opportunity of putting the dose into the water.”

“Clare, this is madness.”

“It sounds like common sense to me.”

With that she went out and left me.

I lay down. So she had the letters and she would show them. Jake and I would be exposed as having had a motive for murder. I would never have hurt Edward willingly. But Jake?

There was no sleep for me all through the night.

I rose early next morning. I went to the stables and saddled a horse. I had to get out of the house. I had to be alone to think. I rode down to the sea and galloped along the shore. There was no joy in the exercise on that morning. One thought was hammering in my mind; Clare had the letters. She it was who had stolen them. I had guessed correctly.

I could not face Jake yet. I was too much afraid of what I would discover.

There was one to whom I had turned during the whole of my life when I was in trouble: My mother.

I left the shore and rode to Eversleigh.

She expressed no surprise to see me. I said: “I have to talk to you at once … alone.”

“Of course,” she said.

She took me into the little sitting room which led from the hall. She shut the door and said: “No one will come here.”

I told her everything—that Jake and I were lovers. I told her of my remorse and my determination not to hurt Edward.

She nodded, understanding.

She said: “It was natural, Jessica. You cannot be blamed.”

But when I told her of the letters which had been written by Jake and stolen by Clare, she was very grave.

“It was clear from what he had written that we had been lovers,” I told her, “that he was impatient and wanted me to go away with him. She threatens to produce them and use them against me.”

My mother was silent. I could see that she was very disturbed.

“I’m afraid,” I concluded. “It will appear that either Jake or I… or the two of us together … planned to kill Edward.”

“Those letters must not be seen by anyone else,” she said.

“Clare has always hated me. She loved Edward and hoped to marry him. Perhaps if it were not for me she might have done so. She will never forgive me, and now she sees this chance …”

“It’s got to be stopped.”

“She is determined.”

“We must get hold of those letters before the inquest,” said my mother firmly.

“She will never give them up.”

She said then what she had always said in the past and which I had often laughed at: “I’ll talk to your father.”

I did not laugh now.

She went on: “My dear, you should go back to Grasslands now. I am going to suggest that Jake comes over to Eversleigh. It would be better that he is not in the house with you. We’ll explain that as things are it is better for him to be with us. Tamarisk is here, and Jonathan is being very good and giving her a lot of attention. It is not right for children to know too much of these things. The Barringtons will be here soon. Clare will be in the house of course. I hope she will not give too much trouble.”

I clung to her. She kissed me and said: “Everything will be all right. Your father and I will see to that.”

Jake saw the point of staying at Eversleigh. I did not have a chance to speak to him alone before he went. I did not seek it. If I had been alone with him I should have had to ask him outright if he had killed Edward, and I was afraid of the answer.

Mr. and Mrs. Barrington arrived. Their daughter Irene and her husband came with them. They had left the children with their paternal grandparents. They were heartbroken. Mrs. Barrington clung to me and wept.

Later we talked together. She said: “He was so noble, my dear Edward. He was always such a good boy, so thoughtful to others … always. When you married him he could not believe his good fortune. Poor dear boy! That he should be the one to suffer from those wicked men! But then you showed your love for him as few would have done, and I shall never forget it. You made him so happy. I blessed the day when you came into his life.”

I thought: Clare will talk to her. Clare will produce the letters. What will she think of me then? What would she say had she known that I had broken my marriage vows? She would have a different opinion of me then.

My parents came to Grasslands. They did not talk a great deal about the tragedy. In fact my father scarcely mentioned it except once when he said: “Poor Edward, he could see no future for himself. I would have been the same. Better to get out than the way it was.”

He had made up his mind that Edward had killed himself and he was the sort of man who would make sure that everyone agreed with him.

It would be different at the inquest. I had never been to an inquest and was unsure of the procedure, but I did know that the verdict was all-important, and it would be decided whether or not this was a case of suicide, accidental death or a case of murder against some person or persons unknown. And if the latter a trial would follow.

It was the day before that fixed for the inquest. My mother sent a message to Grasslands asking me to come over to Eversleigh.

I went immediately.

It was late afternoon and the house was quiet. She was waiting for me in the hall. She said: “Jonathan has taken Tamarisk for a ride. Jake has gone with them.”

“What has happened?”

“Come up to our bedroom,” she said. “Your father is there.”

“Something has happened. Do tell me.”

“Yes. You can trust your father to act.”

He was there in the bedroom and to my surprise Mrs. Barrington was with him. She kissed me warmly. “I expect you are surprised to see me here,” she said.

My father put his arms round me and kissed me.

“Sit down,” he said. “Everything is going to be all right. The inquest is tomorrow and there is going to be a verdict of suicide.”

“How?” I stammered.

“I’ve talked to Jake. I know he had no hand in Edward’s death.”

“How can you know?”

“Because he said so. I know men. I know he would not have been such a fool as to do a thing like that. He was confident of getting Edward’s understanding and you your freedom.”

“He had not spoken to Edward!”

“No, but he intended to.”

“Then how do you know … ?”

“Toby has told me that Edward spoke to him two nights before his death. He said he thought there was little point in his going on living. He said, ‘I am sometimes tempted to slip in an extra dose. That would finish the job and I’d slip quietly away.’ That will be important evidence and Toby will give it. There will be no one who had the slightest reason for wanting Edward’s death.”

I said: “What of the letters?”

My father put his hand in his pocket and drew out two sheets of paper. I snatched them from him.

“Where did you get them?”

“I have them. That’s the important part. I wanted you to be here … to be sure. These are the letters?”

“Why yes. But I don’t understand …”

There was a lighted candle on the dressing table. I had vaguely wondered why it was there as it was not dark. He took the letters from me and held them out to the flame. We watched them burn.

“There!” said my mother, blowing out the candle. “That is an end of that.”

“Did Clare give them up?” I asked.

My mother shook her head. “I took Mrs. Barrington into my confidence. When I explained everything to her she understood …”

She smiled at Mrs. Barrington who said: “Yes, Jessica my dear, I understood. You brought great happiness to my son. He was never so happy as he was through you. I am for ever grateful. Your mother made me see that you loved this man, and he you… and I love you all the more for not leaving Edward but staying by his side. I want to help you. Clare can be of a jealous nature. She was always a difficult child, always looking for slights. Edward could manage her better than the rest of us, and she was very fond of him. I did think at one time that they might have married… but it turned out otherwise, and he was so happy with you. I wanted to help, so when I knew there were incriminating letters I was determined to find them.

“Clare has a very special box which Edward once gave her. It was on her fourteenth birthday. It was very precious to her. In it she kept her treasures. Clare is a creature of habit. She always kept the key to that box on a key-ring—another present of Edward’s—and it was kept in the third drawer of her dressing table. I guessed that the letters would be in that box and I knew where the key was. Poor Clare, she has always been an unhappy girl. She came to us when she was seven. She was a distant cousin’s child. Her parents had been poor. Her mother had died and her father had very little time for her. He was glad when we offered to take her. She was an envious child. Perhaps if her life had been different, she would have been. She always had to remember misfortunes and thought other people should suffer as she had. The only time she was really happy was when she was with Edward. It might well be that he would have married her if you hadn’t come along. People drift into these things. I think she would have been a different girl if he had. Well, I knew of the box and I knew of the key. I chose an opportunity when she was out. It was quite simple. I went into her room. I took the key and opened the box and, as I expected, there were the letters. I brought them to your mother.”

“You have done this … for me?” I cried.

“How can we ever thank you,” said my mother warmly.

“I knew in my heart that it was what Edward would have wanted. The last thing he would have wished would have been for you, Jessica, to be unhappy. So I am doing this for Edward as well as for you.”

My father said: “This will make all the difference. There will be no accusation now.”

My relief was so intense that I could not speak.

My father took my arm and led me to a chair. I sat down beside my mother and she put an arm round me.

“This will pass, my darling,” she said. “Soon it will be like some hazy nightmare … best forgotten.”

I went back to Grasslands. I should have been easier in my mind but the gloom had returned to hang over me. I felt as though I were groping in the dark and at any moment would come upon a terrible discovery.

I wanted to see Jake … desperately I wanted to. I wanted to talk to him … to ask him questions, to beg him to tell me the truth. I did not think he would lie to me. Did he hold life cheaply? Once he had killed a man and felt no remorse for that. What sort of life had he led on that convict ship? He must have seen death and horror in various forms. Did that harden a man? Make him hold life cheap? Make him determined to get what he wanted no matter the cost?

Yes, I wanted to see him and I dared not see him.

As I approached the house I noticed a rider coming towards me. It was Peter Lansdon, one of the last people I wanted to see at that moment.

“Jessica!” he cried.

“Hello.”

“Amaryllis is coming over to see you. She’s very anxious about you. You look drawn. This is a terrible business.”

I was silent.

“Have you just come from Eversleigh?” he asked. “I suppose the parental wits are being exercised to fullest capacity.”

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“This kind of situation … it’s always difficult for the spouse in the case. It’s a commentary on marriage, I suppose, that when a man or woman dies mysteriously, the first suspect is the wife or husband.”