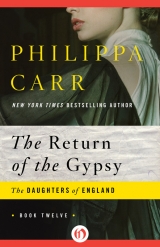

Текст книги "The Return of the Gypsy"

Автор книги: Philippa Carr

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

Peter Lansdon told her what he had told me.

“Insatiable curiosity, I have to admit. I saw you at the Green Man and remembered you. Then I happened to be in Bond Street this morning and recognized your daughter.”

“Thank God you were!”

“I thought there was something suspicious about the blind girl.”

“I was telling Mr. Lansdon how observant he is,” I said.

My mother nodded.

“So … I have to admit, I followed at a distance. I saw your daughter go into the house.”

“And you knew what sort of place it was?”

“I have heard mention of it. I believe at one of the clubs. I could not understand why your daughter should have been taken there by this girl… whose blindness seemed to have come on rather suddenly. Acting on impulse, I went in.”

“You must dine with us tonight,” said my mother. “That is if you are free.”

“I shall be delighted.”

He left us after half an hour.

“What a charming man!” said my mother.

When my father came in and heard what had happened he was first of all astounded and then so angry that I thought he was going to have an apoplectic fit.

He turned on me. “How could you have been so foolish! You don’t seem to have any notion of what can go on in a big city. The idea of going into a strange house …”

“The girl was blind … so I thought. She seemed so pathetic.”

“Pathetic indeed! And you were an idiot.”

I accepted his scorn meekly, feeling it was deserved and now that the ordeal was over I was beginning to feel rather excited. The tall man in the brown beaver hat had taken on a personality and it was a very interesting one. He was coming to dinner and I was sure that acquaintance with him could be stimulating.

My father said to my mother, “Keep the girl in. You never know what folly she’ll be capable of. And, remember, Jessica. You are not to go out alone in any circumstances. Have I made that clear?”

“You have.”

“Then give me your promise.”

I did.

My father went out soon after that. He was bent on making enquiries about number nineteen Grant Street.

To my mother I had to repeat over and over again what had happened: how the blind girl had approached me, what had been said in the house. She kept saying: “Thank God for that young man. I must say he was charming … so self effacing. He really seemed as though he did not think he had done anything very wonderful. To go into a house like that… Goodness knows what might have happened to him. And for the sake of a stranger too … someone to whom he had not even spoken. I think he is wonderfully brave and gallant too. I am so glad he is coming to dinner.”

My father came back some hours later. He had made enquiries about the house in Grant Street. It had been a brothel run by a woman calling herself Madame Delarge who was said to be French. There was no one there at the time. The place was about to be sold. Madame Delarge had what she called a reputable establishment in Piccadilly. She entertained gentleman callers it was true, but there was no enforcement of girls. Everyone came willingly. She had left the house in Grant Street and it had been vacated by her staff a week before. She could not imagine who the people were who had lured a young girl to the place. It was nothing whatever to do with her. She could only believe someone was playing some sort of joke.

More enquiries were made and it seemed that Madame Delarge was speaking the truth.

It was very mysterious, said my mother; and my father was baffled.

“A watch will be kept on the place,” he said.

The adventure seemed to have become more curious than ever.

Peter Lansdon dined with us that evening.

My father’s discoveries about the house in Grant Street had made him even more grateful towards my rescuer. He thought it was very odd that the house had been used by people unknown to Madame Delarge. He thought there was something very suspicious and sinister about the whole matter. He believed that there were organizations which abducted young women and took them out of the country to serve in houses of ill fame in foreign places and the thought that this could have happened to his own daughter roused his anger to such heights that my mother was afraid for him. He was having further investigations made.

“My dear Jessica,” my mother kept insisting, “you must be more careful.”

I promised that I would indeed and I felt very ashamed to have been so easily duped.

Peter Lansdon proved to be an interesting guest.

The dinner was just for the four of us. My parents had thought it better not to ask others. They did not want it known what a narrow escape I had had, and my father—who was by nature suspicious—wanted to know a little more about Peter Lansdon before he introduced him to our friends.

Peter Lansdon was willing—almost eager in fact—to talk about himself.

He had recently come to this country, he said. His family owned estates in Jamaica and had exported sugar and rum in large quantities. A year ago he had decided to sell out his holdings and settle in England.

“Such matters take longer than one at first anticipates,” he explained.

My father agreed with this. “And what are you planning to do now that you are in England? I can see you are a young man who would not wish to remain idle … not one of those gentlemen about town who spend most of their time gambling in clubs.”

“You have assessed me accurately, sir. Indeed, that is not my wish. I had thought that I might buy an estate somewhere and settle here… somewhere in the south. Having been accustomed to a warm climate, I might find the north too invigorating.”

“Have you looked for anything yet?” asked my mother.

“I have seen one or two … nothing which pleases me.”

“Have you a place in London?”

“Not yet. I have been travelling around. I am in a hotel at the moment. Exploring as it were.”

“My daughter tells me that you saw us at the Green Man.”

I smiled at him. “I remember you were in the parlour when we arrived.”

He nodded.

“And you recognized my daughter when you saw her in the street,” said my father.

“Well,” he smiled warmly, “she is rather noticeable. My interest was aroused when I noticed the girl who was pretending to be blind.”

“An extraordinary business,” said my father. “The place was deserted when I called a few hours later. They must have left hastily. Madame Delarge who owns the place knew nothing of them.”

“She is a Frenchwoman?”

“I’m not sure. Posing as one perhaps. Why do they think the French are so much more expert at vice than we are?”

“Perhaps because they are,” I suggested. “Vice must be rather like fashion. There has to be a special elegance … otherwise it becomes quite sordid.”

Peter Lansdon laughed. “There is something in that, I suppose,” he said. “I have made enquiries too and I cannot believe that this Madame Delarge who seemed to be very desirous of keeping what she calls her reputation would stoop to such actions as these people did. It was so crude and so absurd.”

“You are making me feel that I was even more foolish than I have been led to believe to be taken in by it,” I said.

“Oh no, no. Who would not be taken in? A poor blind girl asks to be helped. It would be a hardhearted person who would refuse.”

“But to go into the house …” I said.

“It all happened so naturally, I am sure.”

“It certainly seemed very strange to me,” said my father, and my mother added: “I shudder to think what might have happened if you had not been there, Mr. Lansdon.”

“Don’t think of it. All’s well that ends well and this has ended very well for me, I do assure you. Coming from abroad I have few acquaintances here and it is a great pleasure for me to dine here with you. I sincerely hope this will not be the end of our acquaintance.”

“There is no reason why it should be,” said my mother.

“I was wondering if you could help me at all. You see, I know so little about this country. Although it is my native land I went to Jamaica as soon as I had finished with school and there I joined my father.”

“Your father is there now?” began mine.

“He died two years ago. He was the victim of a virulent fever, endemic to Jamaica. He had suffered from it a few years before. That had a weakening effect…” He shook his head sadly.

“And you decided you would leave,” I asked.

“One has a feeling for one’s own country. One wants to be among one’s own people … the same ideals … the same way of thinking … You know what I mean.”

“I understand perfectly,” said my mother. “I feel the same. I went to France when I was about twelve or thirteen. My first husband was French. But I always regarded England as my home.”

Peter Lansdon was looking at me.

“No, no,” said my mother. “This is Jessica’s father. By my first marriage I have a daughter, Claudine, who is married to my husband’s son. I also have a son who is in France.”

“I see.”

“A complicated relationship,” she added.

“But you understand how I felt about coming home.”

“Perfectly. One day you must meet my other daughter—Jessica’s half sister.”

“That would be a great pleasure. In what part of the country is your estate, if I may ask?”

“The south east. We are only a few miles from the sea. Our nearest big town is Dover.”

“Oh, that part of the country? Is it fertile?”

“Yes. Our bane is the south east wind. That can be pretty fierce. But as you know in the south of England we enjoy a fairly temperate climate. Farming is good. It’s quite a reasonable spot.”

“I shall have to explore.”

“I wonder …” began my mother; and I knew she was thinking about Enderby.

“Yes?” asked Peter Lansdon.

“There is a house which could be rented. It’s quite close to us. It belongs to someone connected with the family and we are looking after it.”

“Really?”

“It would be a good place to look round from, wouldn’t it, Dickon?”

“I don’t know of any estates up for sale in the area,” said my father.

“What about the house itself?” asked Peter Lansdon eagerly.

“There isn’t a lot of land attached to it.”

“Could one acquire land?”

“It might be possible. Our estate covers most of the area round there, and there is another house, Grasslands. There are two farms attached to that.”

“It seems promising. What is the name of this house?”

“Enderby,” I said.

He smiled. “I wonder …” he said.

After the meal we went into the drawing room and Peter Lansdon talked to my father about Jamaica and the exporting of sugar and rum. My father was always interested in business projects and I think found Peter Lansdon’s company entertaining. My mother had taken a great liking to him—largely I think because he had rescued me.

As for myself I was certainly intrigued. He had a special way of looking at me which told me that he admired me, and I guessed that the reason why he had been so interested was on my account.

He left us at ten thirty to go back to his hotel. My mother came up to my room and sat talking for a while.

“What an interesting young man! I am so glad he came to dinner.”

“He seemed delighted to come.”

“I daresay he hasn’t many friends … coming so recently from Jamaica. My dear child, I thank God for that young man. When I think …”

“Oh, please, Mother, don’t go over it all again! I was foolish. I was gullible. But I have learned my lesson.”

“As long as you have …”

“Well, of course I have. It is experiences like that which make us wise. I’ll never be caught like that again.”

“You have to have your eyes open in a city like London.”

“I know that now.”

“Well, we have made the acquaintance of this interesting young man and your father is so grateful to him. Wouldn’t it be amusing if he came to Enderby.”

“Amusing?”

“I mean interesting. It’s odd. But we met the Barringtons through a chance encounter and they came to Grasslands.”

“I don’t think he would want to live at Enderby. It’s not a very enticing house.”

“No, but other things might be … enticing.”

“What do you mean?”

“I think he was rather taken by you.”

“Mother! You are incurably romantic.”

“Well, you are young and very attractive.”

“In your maternal imagination perhaps.”

“I think he is very interesting. I hope we see more of him.”

I was thoughtful after she had gone. It had been a strange day. I went on reliving those terrifying moments in that room in Grant Street. It was very odd and I could believe I had dreamed the whole thing but for Peter Lansdon. I could not get the memory of him out of my mind.

It was small wonder that I found sleep evasive; and when I did sleep I dreamed of him vaguely.

And the first thing I thought when I awoke was: I wonder if I shall see him again.

How life had changed in our neighbourhood—and all within the space of a few years. One thing is altered and then another and another until it is an entirely different scene. It was not completely different because all remained more or less the same at Eversleigh. But Grasslands, where once the rather odd Mrs. Trent had lived with her grand-daughter, was now the home of the somewhat conventional Barringtons; and Aunt Sophie was dead and we had Peter Lansdon at Enderby.

My parents had not thought for one moment that he would take the house. I had secretly held different views. I was beginning to think that he had fallen in love with me at first sight; and I found that exceedingly gratifying and romantic. From the moment he had seen me in the Green Man, he had been interested. He had questioned our coachman; he had seen where I lived in Albemarle Street and by great good luck he had followed me on my adventure to Grant Street.

This last had made a very special bond between us—and indeed with the family, who could never be grateful enough to him.

So I was not altogether surprised when he decided he would take Enderby for three months while he, as he said, “spied out the land”; and I was almost certain that he had come there to be near me.

I enjoyed his society very much and we saw a good deal of each other. My mother took him under her wing and procured servants for him. She invited him to our house frequently and he was now on very friendly terms with the family. Even my father enjoyed talking to him. Amaryllis thought him very charming—one of the most pleasant men she had ever met, she commented.

The Barringtons were slightly less enthusiastic; but I think that was because they felt he might be a rival to Edward.

I had thought a great deal about Edward since the arrival of Peter Lansdon. In Peter’s company I felt stimulated; in Edward’s interested and cosy, but not in the least excited.

At this time Edward was having a great deal of anxiety at his factory and this made him preoccupied; moreover he was away for long periods at a time. His parents were very worried about him and so was Clare Carson. I think she was rather pleased by the advent of Peter Lansdon, which confirmed my suspicions that she was in love with Edward.

Life had become very interesting since Peter was the tenant of Enderby. I was extremely gratified that he had gone to such lengths to be near me and I supposed this endeared me to him. I was still waiting for that great excitement which I connected with being in love. I had believed in it so fervently long ago when I had watched Romany Jake dancing round a bonfire. I had to grow up, I reminded myself. I would have to marry soon. It was expected of me. I thought I was fortunate to have two suitors and was rather sorry for Amaryllis who had no one.

It would be Peter, of course. Our meeting had been so romantic. Poor Edward, he would be heartbroken. I was very sorry because I was fond of him and the last thing I wanted was to hurt him. Perhaps he would marry Clare. That would be a satisfactory conclusion for everyone.

Peter had been so enthusiastic from the first and determined to take Enderby. He had travelled back to Eversleigh with us on that first occasion and my mother invited him to stay with us for a day or so.

He had been fulsome in his praise of our home. “A perfect example of Elizabethan architecture,” he had called it; and he had wanted to know as much as he could about the family.

“It is what one misses when one makes one’s home abroad,” he said. “Oh, how I envy you!”

He studied the portraits in the gallery and asked questions about them. He rode round the estate with Amaryllis and me, and he was charmingly courteous to us both.

I was with my mother and Amaryllis when we took him to see Enderby. I wondered what he would think of it for it looked particularly gloomy as it did on winter days.

I studied him closely trying to see what his first impression was as we went into the hall—that gloomy old hall with the minstrels’ gallery and high vaulted roof.

“It has an atmosphere,” he said. “Not as grand as Eversleigh, but nevertheless splendid in its way.”

We went up the stairs, through the bedrooms.

“Rather a large house for one gentleman,” said my mother.

“It’s a family house,” he agreed.

“It’s a house that needs people,” said my mother. “My aunt, the last occupant, had just herself and her maid. Before that it stood empty for so long.”

“You are not afraid of ghosts, I hope,” said Amaryllis.

“I don’t think Mr. Lansdon is afraid of anything,” said my mother warmly.

“There might be something,” he admitted. “But ghosts certainly not.”

“It’s interesting to look at the old house,” said Amaryllis. “I must confess I never liked the place.”

“Are you trying to discourage me?” he asked.

“Oh no … no … It’s for you to say. I often think places have different effects on people. Some feel one thing, others another.”

“Do you really think there is a possibility of your taking this place?”

“It could not be better situated for my purposes.”

He smiled directly at me and Amaryllis.

I said: “You have decided to look round this area for a suitable place to buy then?”

“I think it might be an ideal spot.”

“Of course,” said my mother, “it is not like buying a place. I don’t think you can get the feel of a neighbourhood until you have actually lived in it.”

We went through the rooms.

“So many of them,” he said.

“Yes, and there is an intriguing speaking tube from one of the bedrooms to the kitchen. I must show you that,” I told him.

“It is a most exciting house. I should like to come and look at it again if I may.”

“Whenever you like,” said my mother. “The girls will come with you. Or perhaps you would prefer to be alone. I often do when I am going to make a decision.”

We talked about Enderby constantly during that day.

“You are certainly letting me know the disadvantages,” he said.

“There are not many advantages to tell you about really,” I replied.

“There is one.”

“And that is?”

“That I should have charming neighbours.”

And before that visit was over he had decided to take Enderby for a short period; and I was sure he had done so, not because the house was suitable but because he was falling in love with me and wanted to be near the family.

He had moved in before Christmas. It was very easy because the place was furnished, just as Aunt Sophie had left it before she died. We seemed to spend a lot of time going back and forth to Enderby and he was often with us at Eversleigh. Amaryllis and I helped him decorate the place for Christmas and he insisted that he entertain us on Boxing Day as he came to us for Christmas Day.

My mother said it was rather touching to see Enderby in a festive mood. There had never been anything like that during Aunt Sophie’s ownership, and before that the place had been empty and neglected. We brought in the yule log and hung a Christmas bush on the door; we stuck up holly and mistletoe in every conceivable place and we decorated the house with ivy.

The Barringtons were invited and I think Mrs. Barrington was a little put out because she wanted us all to go to them on the important days and it was she who had to have her Christmas party on Christmas Eve.

When I had danced with Edward at Grasslands he had once more asked me to marry him. I told him I was still undecided. He was rather sad—anxious about Peter Lansdon’s coming into my life. I was sorry for him and should have liked to comfort him because he was going through such a difficult time; but I did not know how to, except by promising to marry him.

On that occasion I had a word or two with Clare Carson. She said: “What an attractive man your friend from London is.”

I agreed with her.

“I wonder how long he will stay at Enderby.”

“He is deciding what he will do now that he is going to settle in England. He has just sold his estates in Jamaica.”

“How fascinating. I expect… you will marry him.”

I flushed hotly. “Why do you say that?”

“I thought it was what he wanted … you too.”

“You know more than I do.”

She laughed and I realized that was something she rarely did. “I should be surprised if it didn’t happen that way,” she said.

I thought: Is it as obvious as that? Or was it a matter of wishful thinking on Clare’s part.

The Pettigrews were spending Christmas at Eversleigh. My father liked Jonathan to come fairly frequently. He would, of course, be the eventual heir and my father was the sort of man to look ahead. He had a certain affection for Jonathan, a grudging admiration which I think meant that he saw in his grandson something of what he had been at his age.

Peter Lansdon was intrigued by the relationships in our family. He said: “It is so complicated that I have to keep reminding myself who is who. It seems odd that Jessica should be your aunt, Amaryllis.”

“Oh yes,” agreed Amaryllis. “It gave her such superiority when we were in the school room and you can be sure she took advantage of it.”

“Jessica would always seize an advantage.”

We were walking home from church at the time. It was Christmas morning and my head was ringing with the Christmas hymns which I loved. I felt so happy that I could have burst into song.

I said: “You make me sound grasping and scheming. Is that your opinion of me?”

He turned to me and took my hand. “I am sorry. I merely meant you are full of energy … full of the desire to enjoy life … which is what it is meant to be.”

“It is true,” Amaryllis confirmed. “Jessica is… how can I put it? … aware. I am far more gullible, more trusting, more stupid I suppose.”

“I will not allow you to say such things.” He had turned his attention to her. “Like Jessica, you are charming …”

“Although so different,” she added.

“You are both … as you should be.”

“You make us sound like paragons,” I said, “which we are not… even Amaryllis.”

“I shall insist on keeping my opinions.”

“You will probably change them when you know us better.”

“I know you very well already.”

“People can never really know each other.”

“You are thinking of the secret places of the heart. Well, perhaps that is what makes people so fascinating. Would you say that?”

“Perhaps.”

“I am still a little at sea about these relatives of yours. Who is the lively young gentleman?”

“You mean Jonathan?”

“Yes, Jonathan. What exactly is his relationship?”

“My father in his first marriage had twin sons—David and Jonathan. Jonathan married Millicent Pettigrew and young Jonathan is their son. David married my mother’s daughter by her first marriage, Claudine. And Amaryllis is the outcome of that marriage.”

“So Amaryllis and Jonathan are cousins.”

“Yes, and I am Jonathan’s—as well as Amaryllis’—aunt.”

“Isn’t it strange what complicated relations we have managed to build up,” said Amaryllis.

“My father likes Jonathan to come here,” I said. “I daresay he’ll have Eversleigh one day, after David has died of course.”

“Don’t speak of it,” said Amaryllis quickly.

“It will be years and years and we all have to go some time,” I retorted lightly.

“And haven’t the Pettigrews got an estate for Jonathan somewhere?”

“They have a fine house but it is not exactly an estate,” said Amaryllis.

“It will have to be Eversleigh for Jonathan,” I put in. “My father will insist. It was lucky that his sons were so different. David was very good for the estate and I believe his brother Jonathan wasn’t interested. He had all sorts of mysterious irons in the fire. He died violently … I think because of them. I am sure he would never have settled down to run the estate. It may be Jonathan will be like his father.”

“My mother says he reminds her so much of him,” said Amaryllis.

“Your father seems to be a man who knows exactly what he wants,” said Peter to me. “And he’ll make sure he gets it.”

“That sums him up perfectly,” I replied. “There will be trouble if Jonathan doesn’t come up to expectations. He is always saying it is a pity David didn’t have a son as well as you, Amaryllis. He is very fond of you but he would have preferred you to be a boy. He thinks David’s son would have been … amenable.”

“You see,” said Amaryllis, “I have a reputation for being easily led.”

“That’s not exactly true,” I replied. “Amaryllis can be firm, but she is inclined to believe the best of people.”

“What a nice compliment for an aunt to pay her niece,” said Peter lightly; he slipped his arms through mine and that of Amaryllis.

We had reached the house.

Peter said goodbye to us and went back to Enderby. He would be returning later for the evening festivities.

It was a very merry party which sat down for Christmas dinner, consisting of the Barringtons, with Clare Carson, Peter Lansdon, the Pettigrews and our own family. It also included the doctor and his wife and the solicitor from the nearby town, who looked after my father’s domestic business at Eversleigh. For several years they had been our guests and the only newcomer was Peter Lansdon. He made a difference to the party. He had all the social graces to make him immediately popular. Clare Carson seemed to like him a great deal—but I think that was largely due to the fact that she believed he wanted to marry me and that I felt strongly about him.

I was thinking a great deal about Edward and it seemed to me that it would be an excellent idea if she married him. She would care for him, sympathize with him; and she knew something about the factory for she had lived with the family in Nottingham since she was a child.

How unfortunate life was! Why did people set their hearts on the wrong people?

I talked to Edward at dinner and asked how matters were faring at Nottingham.

He said: “No doubt you have heard that these people are getting more and more violent. It is not just confined to Nottingham now. It is spreading all over the country. This cursed French revolution has a lot to answer for.”

“Indeed it has in France.”

“Something like that can’t happen without sending its reverberations all over the world.”

“What will happen about these people who are breaking up the machines?”

“Penalties for the culprits must get harsher. It is the only way to stop it.”

“You mean … transportation?”

“That… and hanging most likely. Only stupid men would not see that you can’t stand still in industry. You have to go forward.”

“Even if it means losing their jobs?”

“Then they must find other jobs. In time the industry will be more prosperous and that will mean more security for them.” He looked at me apologetically. “Hardly the subject for the Christmas feast.”

I put my hand over his. “Poor Edward,” I said. “It is hard to forget it.”

He pressed my hand. I think Peter saw the gesture and I thought with a little touch of excitement: He will be jealous.

I was young. I was frivolous. I was vain; and I could not help being excited because two men were in love with me. I liked Edward so much and I was very sorry for him. If Peter asked me to marry him … when Peter asked me to marry him… what should I say? I could not shilly-shally for ever. The circumstances of our meeting had been so unusual, so romantic. Of course I was going to marry Peter. I was not sure whether I was in love with him. I was very much a novice when it came to falling in love. I felt this was not quite how I ought to feel. But I must be in love with Peter.

My father was talking across the table to Lord Pettigrew who was seated opposite him. I heard my name mentioned and realized they were talking about the adventure and how Peter had rescued me.

Peter was alert, listening.

“I am still making enquiries,” my father was saying. “I don’t intend to let the matter drop. I am going to sift it out.”

“Difficult to trace … The place is empty, you say.”

“The Delarge woman is said to own the place. I don’t believe that. I wonder if there is someone behind her. I’m keeping my eyes open.”

Conversation buzzed round us and continued in a light vein until the meal was over and the hall cleared for dancing.

Peter was a good dancer. He danced with me and then with Amaryllis. That left me free for Edward, who danced rather laboriously—correctly but without inspiration.

“You ought to come for a visit to Nottingham,” he said. “Your mother told me she would like to. She and my mother get on so well together.”

“Yes, it would be interesting,” I said.

“It is a very pleasant house really, lacking the antiquity of this one, of course. But it’s a good family house … some way from the town and we are surrounded by green fields.”

“Perhaps we can come in the spring,” I said. “Edward, I do hope your troubles will be over by then.”

“They must be. They can’t go on. The law will be more stringent and then we shall see changes.”

“Your parents are worried.”

“Yes, about me … in the thick of it.”

“Oh Edward … take care.”

He pressed my hand. “Do you really care?”

“What a stupid question! Of course I do. I care about your whole family … your mother, father, you and Clare. Clare is very worried about you, I believe.”

“Oh yes, she is one of the family.”

I thought how pleased I should be if he and Clare married. I would cease to have a conscience about him then.

“You haven’t made up your mind … ?”

I wanted to say: Yes, I have. I think I shall marry Peter Lansdon, but how could I say that when he hadn’t asked me? All I was aware of was that being with him was exciting, exhilarating, and the manner of our first meeting had seemed so unusual, so adventurous that it was significant.

I said hesitantly: “N-no, Edward. Not yet.”

He sighed and I was very worried because I was going to hurt him. It seemed so sad in view of all his business problems.

I wished I could have made him happier. If I promised to marry him he would have forgotten his business troubles for a while at any rate. And how pleased his parents and mine would have been! At the same time I felt a little irritated with him. It is a sad commentary on human nature that when one could help and doesn’t one begins to dislike the person who arouses one’s pity … largely because one hates feeling uncomfortable, I suppose.