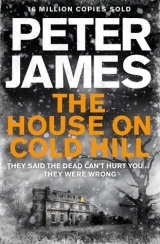

Текст книги "The House on Cold Hill"

Автор книги: Peter James

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

13

Monday, 14 September

‘I’m being shown a house,’ Kingsley Parkin said, totally out of the blue.

‘I beg your pardon?’ Caro said to her client.

‘A house! I’m being shown a very big country house – not far from Brighton!’

Caro’s modern office, in the centre of Brighton, had a window that looked directly down on the courtyard in front of the city’s Jubilee Library. Not that she ever had time to take in the view. From the moment she arrived in her office, in the small law firm in which she was a junior partner, before 8.00 a.m. every morning, she was full-on, reading documents, drafting and redrafting transfers and leases. At 9.00 a.m. the phone would begin to ring, incessantly, until the switchboard closed at 5.00 p.m. Some clients would email or phone her – or both – several times a day, anxious about properties they were buying or selling.

Additionally, she had meetings throughout the day both with existing clients and to take new instructions. Mostly she enjoyed face-to-face meetings, they were her favourite part of her work. She had a natural instinct to help people, and she enjoyed the challenge of pointing out pitfalls in property transactions. But with the way her days stacked up, she needed to keep her client meetings as brief as possible and to the point; there was little time to spare for small talk.

Which was why this new client, seated in front of her, a pleasant, but very, very long-winded man, vacillating over whether to bid for a potential student housing property which was shortly coming up at auction, was beginning to irk her.

He was an elfin creature, of indeterminate age somewhere north of sixty, in a high-collared emerald shirt beneath a shiny black jacket on which the tailor’s white stitching was part of the design, silver trousers, and patent-leather Cuban-heeled boots. His fingers were adorned with large jewelled rings. His hair was jet black, his skin was pockmarked and sallow, as if rarely exposed to daylight, and he reeked of tobacco. He’d once been the lead singer of a 60s rock band that was something of a one-hit wonder, and had scraped a living doing pub gigs and cruise ships on the back of it ever since, he had told her. Now he was looking to shore up his finances for his old age with some property investments.

‘There are a couple of things I need to make you aware of,’ Caro said, reading through a long email from the vendor’s solicitor, a particularly sharp character called Simon Alldis.

Mr Parkin picked up his cup of coffee and held it daintily in the air. ‘Listen, my love,’ he said in his coarse, gravelly voice. ‘I’m being told something.’

‘Told something?’

‘Happens to me all the time. The spirits won’t leave me alone – know what I mean?’ He flapped his hands in the air, as if they were a pair of butterflies he was trying to shake free from his bangled wrists.

‘Ah.’ She frowned, not knowing what he meant at all. ‘Spirits?’

‘I’m a conduit, my love, from the spirit world. I just can’t help it. They give me messages to pass on.’

‘Right,’ she said, focusing back on the document in the hope it would concentrate his mind on the business in hand.

‘You’ve just moved into a new house, Mrs Harcourt?’

‘How do you know that?’ she asked sharply, uncomfortably surprised. She did not like her clients knowing about her private life, which was why she kept her office bland, with just one photograph facing her on her desk, of Ollie and Jade holding paddleball bats on the beach in Rock, Cornwall.

The two butterflies flitted around above his head again. ‘I have an elderly lady with me, who passed last year!’ he said. ‘You see, the spirits tell me things, I can’t switch them on and off. I hear a click and then someone is there. They can be very irritating sometimes, you know? They can piss me off.’

‘Who tells you?’

‘Well, it varies, you see!’

‘Shall we concentrate, Mr Parkin?’ She looked back down at the document on her desk.

‘I have a message for you,’ he said.

‘That’s very nice,’ she said, sarcastically, glancing at her watch, the Cartier Tank that Ollie had bought her for their tenth wedding anniversary. ‘The document I have here—’

He cut her off in mid-stream. ‘Can I ask you something very personal, Mrs Harcourt?’

‘I have another client immediately after you, Mr Parkin. I really think we should concentrate.’

‘Please hear me out for a moment, OK?’

‘OK,’ she said, reluctantly.

‘I don’t go looking for spirits, right? They find me. I’m just passing on what I get told. Does that make any sense?’

‘Honestly? Not much, no.’

‘I’m being shown a house. A very big place, Georgian-looking, with a tower at one end. Does that mean anything?’

Now he had her attention. ‘You saw the estate agent’s particulars?’

‘I’m just passing on what the spirits are telling me.’ He shrugged. ‘I’m just a conduit.’

‘So what are these spirits telling you?’

‘This is just one particular spirit. She wants me to tell you there are problems with your new home.’

‘Thank you, but we already know that.’

‘No, I don’t think you do.’

‘We’re well aware of them, Mr Parkin,’ she replied, coldly. ‘We had a survey done and we know what we’re in for.’

‘I don’t think what I’m being told would have shown up on a survey, my love.’

His familiarity annoyed her.

‘There are a lot of things you don’t know about this house,’ he went on. ‘You’re in danger. There are very big problems. I’m being told you really ought to think about moving out, while you still can. Your husband, Ollie, your daughter, Jade, and yourself.’

‘How the hell do you know all this about us?’ she rounded on him.

‘I told you already about the spirits. They tell me everything. But many people don’t like to believe them. Maybe you are one of those?’

‘I’m a solicitor,’ she said. ‘A lawyer. I’m very down to earth. I deal with human beings. I don’t believe in – what do you call them – spirits? Ghosts? I’m afraid I don’t believe in any of that.’ She refrained from adding all that rubbish.

Kingsley Parkin rocked his head, defensively, from side to side, the butterflies soaring once more, light glinting off the rubies, emeralds and sapphires. ‘Admirable sentiments, of course!’ he said. ‘But have you considered this? Ghosts might not care that you don’t believe in them? If they believe in you?’

He grinned, showing a row of teeth that looked unnaturally white. ‘You’re going to need help very soon,’ he said. ‘Trust me. This is what I’m being told.’

She was beginning to feel very unsettled by the man. ‘Told by whom?’

‘I have this elderly lady with me who passed in spring last year. She had a grey cat who passed the year before, who is in spirit with her. She’s telling me her name was – hmmm, it’s not clear. Marcie? Maddie. Marjie?’

Caro fell silent. Her mother’s sister, her aunt Marjory, had died in April last year. Everyone called her Aunt Marjie. She’d had a grey cat which had died a few months before she did.

14

Monday, 14 September

Ollie left the old lady, Annie Porter, his head spinning. She was wrong. She must be. Maybe her memory wasn’t too great.

He walked on down into the village, deep in thought, as the tractor driven by grim, surly Arthur Fears, local farmer and frustrated Formula One driver, rocketed by, blasting him with its slipstream. He passed the village store, then hesitated when he reached the pub. Much in character with the village, The Crown was a Georgian building, but with a rather shabby extension to the left covered with a corrugated iron roof. It was set well back from the road, with a scrubby, uneven lawn in front of it, on which were dotted around several wooden tables and benches – a couple of them occupied.

He walked up the path. In small gold letters above the saloon bar door, were the words:LICENSED PROPRIETOR, LESTER BEESON.

If he ever had to create the interior of an iconic English country pub for a website, Ollie thought, as the ingrained sour reek of beer struck his nostrils, this place would be it. Booths recessed into the walls, wooden tables and chairs, window seats, and a warren of doorways leading to other rooms. The ochre walls were hung with ancient agricultural artefacts, and there was a row of horseshoes along one side, along with a dartboard.

Presiding over the L-shaped bar was a massively tall man in his late fifties, with a mane of hair, a cream shirt with the top two buttons undone and a gut the size of a rugby ball bulging his midriff. Behind his head were rows of optics, a photograph of a cricket team, and several pewter tankards.

‘Good afternoon,’ the landlord greeted him warmly, lifting a pint glass up and drying it with a cloth.

‘Good afternoon!’

‘Mr Harcourt would it be, by any chance?’ He set the glass down.

Ollie grinned, surprised. ‘Yes.’ He held out his hand. ‘Ollie Harcourt.’

The landlord shook it firmly. ‘Les,’ he said. ‘All of us in Cold Hill are very happy to have you and your family with us. We need a little rejuvenation. What can I offer you as a drink on the house?’

Normally, Ollie avoided drinking alcohol at lunchtime, but didn’t want to look a prig. ‘Well, that’s very kind of you, thank you. I’d like a draught Guinness – and also a lunch menu, please.’

The plastic-coated menu appeared in front of him instantly, as if conjured from out of the ether by the landlord. The Guinness took some minutes longer. As Lester Beeson stood over the glass, which was steadily filling with black liquid and cream foam, Ollie ventured, ‘Do you by chance know an old guy in the village, with a briar pipe and walking stick?’

‘Pipe and walking stick?’ He thought for a moment. ‘Doesn’t ring a bell. Local, is he?’

Ollie nodded. ‘A wiry little fellow with a goatee beard and very white hair. In his seventies or even eighties?’

‘No, doesn’t ring any bells.’

‘I understand he lives here, in the village. I met him last week – I wanted to have another chat with him.’

‘I thought I knew everyone.’ The landlord looked puzzled. He turned towards an elderly, morose couple seated in a window booth, eating in silence as if they had run out of conversation with each other years earlier. ‘Morris!’ he called out. ‘You know an old fellow who smokes a pipe and has a walking stick?’

After some moments the man, who had lank white hair hanging down either side of his face, as if a damp mop had been plonked on his head, set down his knife and fork, picked up his pint of beer and sipped it.

Ollie thought at first he couldn’t have heard the landlord. But then he said, suddenly, in a northern accent, ‘Pipe and a walking stick.’ He licked froth from his lips, revealing just two teeth, like a pair of tilting tombstones, at the front of his otherwise barren mouth.

The landlord looked at Ollie for confirmation. He nodded.

‘That’s right, Morris. A beard and white hair,’ Beeson added.

The old couple looked at each other for a moment and both shrugged.

‘He’s as old as God, Morris is!’ Beeson said to Ollie with a grin, and loudly enough for the old man to hear, then turned towards him. ‘You’ve been here in the village – what – forty years, Morris?’

‘Forty-two it is, this Christmas,’ the old woman said.

Her husband nodded. ‘Aye, forty-two. We came down here because our son and his family moved here.’

‘Morris were engineer on the railways,’ she said, inconsequentially.

‘Ah,’ said Ollie, as if that explained everything. ‘Right.’

‘Don’t know of anyone like that,’ she said.

‘I’ll ask around for you,’ Beeson said to Ollie, helpfully.

‘Thank you. I’ll give you my home and mobile phone numbers – if you hear anything.’

‘If he lives anywhere around here, someone will know him.’

‘Old as God, did you say?’ the old man suddenly called out to Beeson. ‘I’ll have you know, young man . . . !’ Then he began chuckling.

Later that day, when Caro came home from work, Ollie again said nothing to her about the strange old man with the pipe.

Caro said nothing to Ollie about her encounter with Kingsley Parkin.

15

Monday, 14 September

With Katy Perry belting out through the Sonos speaker, Jade sat at her dressing table, which doubled as her desk, doing her maths homework, and allowing herself – willing herself – to be distracted by just about anything. She hated maths, although at least her new teacher at St Paul’s made it more interesting than the dull one at her old school.

That, she had gleefully Instagrammed to all her old friends, was one very big plus of St Paul’s. No more annoying Mr G! God, he was so dreary. So – well – just so annoying.

Annnnnooooooyyyyyyyyinggggg! she typed out and posted beneath a photograph she had taken, surreptitiously, of Mr G in class some months ago, then pinged it to all her old schoolmates.

She put her iPhone back down on the table, then watched several ducks in the distance swimming in convoy across the lake, heading to their island sanctuary in the middle. Good, she thought. Smart ducks! Keep safe from the foxes overnight! As if reading her mind, Bombay suddenly arched her back, jumped down from the bed, walked over to the water bowl Jade kept up here for her, and began lapping at it.

‘I bet you’d like a duck if you weren’t so lazy, wouldn’t you, Bombers?’ She slipped off her chair, knelt beside the cat and began stroking her. Bombay nuzzled her head against Jade’s hand and started purring. ‘But I would not be happy about that, OK? No ducks!’

Her room was a lot straighter now, at least, with all of her things out of the boxes and on shelves or in cupboards. But she wasn’t entirely happy. She still felt too isolated from her friends. And Ruari wasn’t messaging her as often as he usually did. What was that about, she wondered, suspiciously? And although there seemed to be some nice people at St Paul’s, she’d not yet made any new friends. In fact, there were a couple of girls in her class who seemed quite bossy and rude.

She sat back at her desk and, instead of returning to her maths, opened up the Videostar app on her iPad and went to the current pop video she was making with Phoebe, which she hoped to complete at the weekend.

In the video, set to ‘Uptown Funk’, she and Phoebe, in matching zebra-striped onesies, were dancing, alternately in colour, then in black and white, then just in silhouette. She’d got the idea from some of the silhouette shows she had watched on YouTube. As the video progressed, they were to fade more and more into silhouette, but the idea was not yet coming across as she wanted.

Her phone rang. She froze the video, picked the phone up and saw it was Phoebe on FaceTime, her blonde hair hanging untidily over her face as normal in a ragged fringe.

‘Hey.’

‘Hey.’

‘Missing you, Jade!’

‘Me too. I wish I was back with you guys.’ Then she paused for a moment. ‘You know what – I was just watching the shadows. I think I’ve had an idea! We can do this over the weekend – I’ve—’

Phoebe frowned. ‘You’ve got a visitor,’ she said, suddenly.

‘That’s Bombay! She’s with me all the time, just like in Carlisle Road.’

‘Not the cat, your gran.’

‘Gran?’

‘Behind you!’

Jade felt a sudden icy chill and spun round. There was no one there. The door was closed. She shivered and turned back to her phone. Then she shot another wary glance over her shoulder.

‘Phebes, my gran’s not here today.’ She was conscious that her voice was shaking.

‘I saw her, honestly, Jade. The same lady that came in last week – last Sunday?’

‘Describe her?’

‘I could see her more clearly this time, she was closer, only a few feet behind you. All in blue, with a creepy old-woman face.’

‘Yeah, yeah, yeah!’

‘No, no, for real, Jade!’

Taking the phone with her, Jade walked over to the door, waited a moment, then pulled it open sharply. There was nothing there. Just the long, empty landing, with closed doors to the spare rooms, the door to her parents’ room some distance along, the stairs up to her father’s office in the tower at the far end, and the staircase down to the hall. ‘There’s no one here. Are you joking, Phebes? You’re trying to spook me out, aren’t you?’

‘Honest, I’m not!’

‘Whose idea is it? Yours? Liv’s? Lara’s? Ruari’s? Trying to freak me out for a prank?’

‘No, I promise you, Jade!’

‘Yeah, right.’

16

Tuesday, 15 September

‘Hey!’ Ollie called out, immensely relieved to see the old man again. He was standing at the bottom of the drive between the entrance pillars, pipe clenched in his mouth, staring up at him, squinting against the intensely bright sunlight. Ollie ran the last few yards as if terrified the old man would walk off. ‘I’ve been trying to find you, but it’s not easy!’

‘No, well, it wouldn’t be,’ he said. ‘That’s for sure.’

He looked exactly as he had last week, with his rheumy eyes, his pipe and his gnarled walking stick.

‘I never got your name?’ Ollie quizzed him.

‘Oh, I like to keep meself to meself.’ He nodded with an almost sage-like expression on his face.

Ollie proffered his hand. This time the old man took it and shook it, weakly, with bony, clammy fingers. ‘I needed to come and find you again, Mr Harcourt, you see. There’s things you need to know about your house.’

‘That’s why I was trying to find you. I wanted to ask you more about what you told me last week. Would you like to come up and have a cuppa, or a cold drink?’

The man looked afraid suddenly and shook his head vigorously, almost in a panic. ‘Oh no, thank you, I don’t drink nothing.’

‘Nothing?’

‘I’m not coming up to the house. Not going near that place, thank you very much.’ He stared at Ollie levelly, his eyes filled with an almost immeasurable sadness. ‘I don’t know what to tell you, that’s the truth. I don’t know. Have you seen her yet?’

‘The lady?’

‘Have you seen her?’

Ollie suddenly had the idea of taking a photograph of the man. If he showed a photograph, then someone would identify him.

He didn’t think the old man would give permission if he asked him straight out, so while they talked he sneaked a glance at his iPhone, which he was holding in his right hand, and swiped the camera symbol up with his thumb. Just as the old man appeared, blurrily, within the camera viewing screen, the phone rang. It was Caro.

Ollie couldn’t believe his luck!

Seizing the chance, he raised the phone and pressed the red button to kill the call, but pretended to answer it. ‘Hi, darling!’ he said. ‘I’m just chatting to a lovely gentleman in the lane. Call you back!’ While he was speaking, the camera viewfinder returned, and still holding the phone up, he took a clear photograph of the man, before pocketing the phone. Then he said to the old man, ‘Apologies, my beloved.’

‘So,’ the old man said again, more insistently. ‘Have you seen her? Have you?’

‘I think both my in-laws may have done.’

Suddenly, gripping his stick with a clenched fist, he looked around, wildly, with fear in his eyes. ‘I have to be on my way now, I have to be off.’

‘Wait, please, can’t you tell me more about this – this thing you saw here? The lady? Is it something we need to be worried about, do you think? There was a big piece on ghosts in the Sunday Times I’ve been reading. It talks about imprints in the atmosphere, energy they’ve left behind, that sort of thing, trapped in a space–time continuum. There’s tons of stuff on the web, all kinds of theories. One is they’re the spirits of people who don’t realize their bodies are dead and haven’t found their way to the next plane. Earthbound souls, I think is the expression. Or that they have unfinished business. They’re spooky, but does anyone actually need to be afraid of them? I mean – can ghosts ever actually do anything?’

‘What about that Hamlet’s father?’ the old man replied.

‘That was a play, it was fiction, just a story,’ Ollie said, surprised to have Shakespeare thrown at him by this man.

Abruptly, the old man turned away, just as he had done the previous time they’d met. ‘I have to go now,’ he said, and started walking off.

Ollie hurried after him and drew level. ‘Please – please just tell me a bit more about her, this lady.’

‘Ask someone to tell you about the digger.’

‘You mentioned it last time – tell me what about the digger?’

‘The mechanical digger.’

‘What digger do you mean?’

‘No one leaves your house. They all stay.’

‘All stay? What do you mean?’

‘Ask about the digger.’

‘What about the digger?’

But the stranger quickened his pace, striking the ground with his stick, staring fixedly ahead in silence, his face livid with anger, as if he resented Ollie’s presence.

Ollie stopped and watched him walk on, feeling confused by the encounter. He turned to go back up to the house, but instead of the long driveway, he was suddenly staring at the front of their old home, their Victorian terrace in Carlisle Road in Hove. He walked slowly towards the front door, feeling as if it were the natural thing to do. As he reached the porch, the door opened, and there was Caro, smiling happily.

‘Darling,’ she said. ‘We have a visitor!’

It was the old man. He appeared in the doorway, looking very comfortable, as if he had come to stay and was settling in nicely, and raised his pipe in the air. ‘Mr Harcourt, nice to see you, welcome home!’

Then a steady peep . . . peep . . . peep . . . peep intruded.

His alarm clock.

He had been dreaming. A weird dream – or a nightmare.

Caro leaped out of bed instantly. ‘Got to get in really early today,’ she said. ‘I’ve got a completion going on this morning and I have to go and see a client who’s in the Martlets Hospice.’

As he heard the sound of Caro in the bathroom, Ollie sat up, remnants of the strange dream still going around his head, and silenced the alarm repeat. 6.30 a.m. God, it had seemed so real, so vivid.

He reached out for his phone to check Sky News, as was his ritual, and saw to his surprise the red low-battery warning. He was sure it had been fully charged last night. Then he realized that the camera app was running.

He wondered if he was still dreaming. Out of curiosity, he clicked on Photos. There was a new image in the bottom left of the screen.

And now for sure he knew he was dreaming.

He jumped out of bed and ran over to the bathroom, his heart pounding. Caro was stepping out of the shower, one towel wrapped round her body, another, like a turban, round her head.

‘Take a look at this!’ he said, urgently, and held up the screen. ‘Tell me I’m not dreaming, please?’

She peered at it for a moment then said, in the acidly pleasant-but-dismissive tone she sometimes adopted when she was required to be polite about something she really did not care for, ‘What a sweet little old man. Why did you photograph him?’