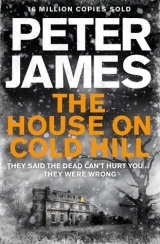

Текст книги "The House on Cold Hill"

Автор книги: Peter James

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

‘I’ll remember that, thank you,’ Ollie said.

‘I’ll give you a bit of advice though – I’ll tell you what I think you should do – I’d have done it myself for you if I’d been a younger man, but I’m too old now.’

Five minutes later, as Ollie drove away, the old clergyman stood by the front door, holding his dog and giving him a strange look that unsettled him.

It was the look of an old man who was seeing something – or someone – for what he knew might be the last time.

It made Ollie shiver.

Manthorpe closed the front door feeling deeply shaken. He needed to make an important phone call, and urgently. He looked around and remembered he had left the handset up in his den on the first floor.

The conversation of the past hour with the decent young man had confirmed so much that he already feared. The Harcourts needed help, and he knew the right person to speak to. He began to climb the narrow stairs, his knees aching, his heart pounding. He was out of breath before he’d reached halfway. Soon he was going to have to find the money for one of those stairlift things. Or else move.

With one step to go to the top, a shadow suddenly crossed in front of him, and stopped.

The old man halted in his tracks and stared up. He wasn’t afraid, just angry. Very angry. ‘What the hell do you want?’ he said.

33

Thursday, 17 September

‘Mr Simpson, the music teacher, has asked me if I’d like to play a solo in the school concert at the end of term!’ Jade said, bubbling with enthusiasm as she climbed up into the car.

‘Wow, that’s great, lovely! What are you going to play?’

‘Well, I’m not sure yet – he’s got a few ideas.’

‘I’m very proud of you!’

All the way home she told him about her day and about how much she liked her new music teacher. The discussion about ghosts they’d had this morning, when he’d been driving her to school, seemed to be gone from her mind – for now at least.

At a few minutes past 6.00p.m., as they drove up the drive and the house came into view, looking stunning in the evening sunlight, his spirits lifted. He was cheered and buoyed by Jade’s happy innocence and her growing enthusiasm for her new school. And she had added two more new friends, in addition to Charlie and Niamh, to the ones she wanted to invite to her birthday party, she told him.

He saw Caro’s black Golf parked outside the house, and then, as they drew closer, he saw she was still in the car, talking on her phone.

He pulled up beside her, and climbed out. Jade jumped down, clutching her guitar and rucksack, and ran happily to the Golf. Moments later, Caro ended her call and emerged, holding her briefcase. Jade hugged her and delivered the same excited news she’d given her father. Then they went inside and Jade disappeared up to her room.

‘How was your day, darling?’ Ollie asked.

‘I need a drink,’ she said. ‘A large one. Several large ones!’

They went through into the kitchen. Caro plonked her briefcase down on the floor. ‘I’m afraid I’ve got a good hour’s work to do,’ she said. ‘But I really do need a drink first. God!’

Ollie went over to the fridge and took out a bottle of wine, then began to cut away the foil. ‘Have you only just arrived home, darling?’

‘No, I got here about twenty minutes ago. I was waiting for you to come home. I’m sorry.’

‘Sorry?’

‘Yes.’

‘Sorry about what?’

She shrugged off her jacket and hung it on the back of her chair. ‘I was too scared to come in here on my own. I – I didn’t want to be alone in the house.’

He turned to look at her. She was hunched over the table, looking deeply vulnerable.

He walked over and put an arm round her. ‘Darling, I understand.’

‘Do you? Do you really? Do you understand what it’s like to be scared to go in the front door of your own sodding home? Aren’t you scared? What’s going to happen tonight? Tomorrow? It’s like something doesn’t want us here. What the hell have we done? What have we got ourselves into? Do you think we should move? Ollie, what are we going to do?’

She was wondering whether she should tell him about the message on her phone that had appeared – then disappeared – whilst she was having lunch with Kingsley Parkin. But she still couldn’t be sure if she had simply imagined it. So she said nothing.

‘We need to sort this out,’ he said. ‘Sort the house out. Find out just what the hell is going on. I went to see the previous vicar here, a nice old boy called Bob Manthorpe. He said the house had a bad history but that all old houses have some tragedies in their past.’

‘And beds that rotate one hundred and eighty sodding degrees during the night?’

‘I still think there’s got to be an explanation for that.’

‘Good, I’m glad one of us does.’

He returned to the wine. ‘It’s not physically possible to have rotated – without being dismantled first. I took Bryan Barker up to the room earlier, and he had a good look at it. The nuts and bolts holding it together haven’t been touched in years – decades. They’re all corroded.’

‘I went to see someone too, today.’

‘Who?’

‘A client. I didn’t want to tell you about him because I didn’t want to upset you. He came to see me on Monday. He’s a new client, a weird guy, an old rocker called Kingsley Parkin – he had one big hit back in the sixties – who says he’s psychic.’

‘What was the hit?’

‘I can’t remember – not something I’d heard of. I think he said his band was called Johnny Lonesome and the Travellers – or something like that. Anyway, he started getting messages about the house when he was in my office on Monday – messages from my auntie Marjorie. Marjie. Remember her?’

‘Of course.’ The cork came out with a loud pop. ‘She was lovely, I liked her.’

‘She liked you, too. He knew her name, Ollie. Isn’t that strange? How did he know her name?’

‘What kind of messages – what was she saying?’

‘He said she was telling us to leave. To leave while we still could.’

Ollie wiped fragments of cork from the neck of the bottle, thinking. If Caro’s mother, despite being a magistrate, was a tad bonkers, her auntie Marjie had been seven miles north of bonkers. He’d genuinely liked her, but she really was wired on a different circuit from everyone else. ‘Did your auntie have anyone in mind to buy this place and pay us back all we’ve sunk into it?’

‘I’m being serious, Ollie.’

‘So am I.’ He filled two wine glasses and carried them over to the table. ‘Look, I’m not going to pretend I’m happy about any of this. I can’t explain the bed, and I can’t explain what you saw in the mirror. But moving here is the biggest thing we’ve ever done. We can’t just walk away because some drug-addled old rocker with a fried brain is getting messages from your dead auntie. Is that what you want?’

‘Kingsley Parkin said that if we wanted to stay we should consider asking for an exorcism. But he’s offered to come out here himself and see what he picks up.’

Ollie sat down opposite her. ‘An exorcism?’

It was along the lines of what Bob Manthorpe had suggested to him earlier, although he had used less dramatic words, a Christian Service of Deliverance, he had called it. And he had told Ollie he knew a good person to do it if they decided to go that route.

‘Parkin said we should talk to the current vicar,’ continued Caro. ‘Apparently there’s an exorcist in every diocese in the country. They get called in when things happen that people can’t explain. Like they’re happening here.’

‘Bell, book and candle. All that stuff?’

‘I’m willing to give it a go. Do you have a better idea, Ollie? Because if so, tell me. Otherwise I’m getting the hell out of here.’

‘Listen, we mustn’t panic, that would be ridiculous!’

‘Like rotating one hundred and eighty degrees in the night is ridiculous? Like seeing an apparition in my mirror is ridiculous? Sure, I can accept that this move here is a big thing and massively disruptive. But we’ve moved into a nightmare.’

‘The old vicar chap, Manthorpe, was going to have a word with someone – someone in the clergy who’s had experience dealing with odd phenomena. But I don’t think it was quite as dramatic as an exorcist.’

‘Why not have an exorcist?’

‘I’m happy to have an exorcist – or whatever he’s called – come here. Let’s do it. Would that make you feel better?’

‘Would it make you feel better?’

‘If he can stop whatever’s going on here, yes.’

‘OK,’ she said. ‘I’ll sort it. I’ll call Kingsley Parkin first and see how soon he could come out here. Maybe he can come this evening. Shall I do that?’

All the time they talked, Ollie continually glanced past her at the archway through into the atrium, looking for the spheres he had seen previously. He glanced around for them, with a shiver, every time he entered the atrium. An exorcist. He shrugged at the thought. But he had no better solution.

He also had a feeling there was more that Manthorpe might have told him, if he’d pressed, if he’d had more time and not had to leave to go and collect Jade. He suspected the old vicar knew more about the history of the house than he was telling. He would call him tomorrow and try to go and see him again, he decided. ‘Sure, call this Parkin chap,’ he said to Caro.

‘I’ll do it now. Let’s carry on this conversation later,’ she said. ‘We’ll make beds up on the sofas. But I’ve got to deal with something urgently for a client.’ Caro leaned down, opened her briefcase and pulled a thick plastic file-holder from it.

‘I’ve got something urgent to do too, for sodding Cholmondley,’ he said. ‘Want me to make supper tonight?’

‘That would be great, thanks.’

‘Stir-fried prawns? We’ve got some raw ones in the fridge.’

‘Anything.’

He looked at his watch. It was coming up to 6.30 p.m. ‘Eat around eight?’

‘Fine.’

As he removed the bag of prawns from the fridge, and poured some into a bowl, Ollie heard Caro on the phone leaving a voicemail message for Parkin. He filled the cats’ food bowls, called them, then carried his wine glass up to his office, sat at his desk, and switched on the radio to catch the closing news headlines.

Earlier that afternoon Cholmondley had sent him an email which he had only looked at, so far, on his iPhone. It was a photograph of a 1965 Ferrari GTO that had sold at auction in the USA for thirty-five million dollars a couple of years back. Cholmondley had now been offered its sister car with, he claimed, an impeccable provenance. He wanted star treatment for it on the website.

As the screen came to life, to Ollie’s surprise all the normal folders and documents on the desktop had vanished. In their place were the words, in large black capitals:

MANTHORPE’S AN OLD FOOL. DON’T LISTEN TO HIM. YOU’LL NEVER LEAVE.

As he stared at them in shock, they suddenly faded away and all the folders and documents came back into view.

Then he heard Caro scream.

34

Thursday, 17 September

With his heart in his mouth, Ollie raced down the stairs, through the atrium and into the kitchen.

Caro was standing, wide-eyed, in the middle of the room. Shards and splinters of glass lay on the table, across her documents, and on the floor. Open-mouthed, she was staring upwards and pointing. He looked up and saw the remains of the light bulb hanging from the ceiling cord directly above the table.

‘It exploded,’ she said, her voice quavering with fear. ‘It just bloody exploded.’

‘It happens sometimes.’

‘Oh, does it? When? It’s never happened to me before.’

‘It’s probably from the flood – water was dripping down here yesterday. Must have caused a short or something – or leaked into the bulb.’ He peered up at it more closely. ‘Looks like it was used in the Ark! Probably some water leaked into it.’

She was shaking her head. ‘No, Ollie. I don’t believe it.’

‘Darling, calm down.’ He put an arm round her. She was trembling. ‘It’s OK,’ he said.

‘It’s not OK.’

‘There’s a perfectly rational explanation.’

‘I’m fed up with hearing you say perfectly rational explanation, Ollie. What’s happening in this house is not perfectly rational. We’re under sodding siege. Or are you in bloody denial?’ She was yelling.

He raised a finger to his mouth. ‘Ssshhh, don’t let Jade hear, I don’t want her freaked out.’

‘She’s up in her room with her music blasting, she can’t hear.’ Caro stared up at the light socket then down at the glass on the table and floor.

‘I’ll get a dustpan and brush and the hoover,’ Ollie said.

‘I’m calling Kingsley Parkin again,’ she said. ‘I want him to come here now, tonight.’

Ollie scooped up as much of the glass as he could with the brush, helped by Caro, who picked up the larger pieces in her fingers. He wondered whether it would help the situation to call his mother-in-law. But he was nervous that the woman, however well-intentioned, might only make matters worse. He emptied the pan into the rubbish bin, then went through into the scullery, returned with the Dyson, and plugged it in. He heard Caro leaving a second voicemail for her medium client. When she hung up, he switched the machine on.

It roared, and there were tiny clinking sounds as it sucked up the smaller, almost invisible glass splinters. Then, suddenly, there was a loud click. The room darkened as the other lights went out. The vacuum cleaner’s motor fell silent.

Caro looked at him, more calmly than he was expecting. ‘Great,’ she said. ‘How great is that?’

Ollie grimaced. ‘The electrics are totally fucked. They’re working on the rewiring but it’s a massive job.’

‘I don’t even know where the fuse box is,’ she said. ‘You’d better show me in the unlikely case I’m ever brave enough to be here on my own.’

He led her through into the scullery and showed her the two new plastic fuse boxes the electrician had fitted this week, up on the wall. He reached up and flipped open their lids, and pointed out the master switch at the end of the lower of the two boxes, which was down. He pressed it up and immediately the lights came back on, and they heard the roar of the Dyson starting up.

‘They’re very sensitive – the RCD trip is a good safety thing.’

She peered along the rows of individual switches.

‘When they’ve finished the rewiring they’re going to label each of them.’

‘Could that bulb exploding have caused this?’ she asked.

He felt relieved that she was taking a rational view. ‘Quite possible, yes, or more likely whatever caused the bulb to blow then caused this. I think we’re going to find it was water from the flood seeping into the electrics that caused both.’

‘I hope to hell you’re right.’

‘They’re due to start the rewiring down here tomorrow,’ he said.

As they walked back into the kitchen, she stared warily around. ‘I don’t know how much more I can take.’

‘I’ll go up and fetch my laptop and work in here with you until supper.’

‘I’d like that.’ She looked up at the wall clock, then at her watch. ‘Why hasn’t Kingsley Parkin called back?’

‘You only rang him half an hour ago. Maybe he’s with a client. Or out.’

She sat back at the table and began looking at a document. ‘Yes, maybe.’ She picked up her phone and dialled the vendor’s solicitor’s home number.

Later, lounging back on a sofa in the drawing room, after their supper of stir-fried prawns, they watched another episode of Breaking Bad. Caro was more relaxed now.

She looked, for the moment at least, Ollie thought, as if she had put her immediate worries behind her. She was enjoying the programme – as well as the second bottle of wine they were now well into.

But Ollie couldn’t concentrate on the television. One moment his eyes were darting warily around, looking at every shadow. The next he was far away. Thinking. Thinking.

Thinking.

The message on his computer screen that had faded within seconds.

Had he imagined it?

Was it possible for a message to appear like that, randomly, and then vanish, given the sophisticated firewall Chris Webb had installed on his computer?

Any more possible than for a photograph of a bearded old man to appear then disappear?

He felt deeply gloomy and his nerves were on edge. This dream home, which they had moved into barely a fortnight ago, had turned into a nightmare beyond anything he could have imagined.

They had to sort it out. They would. They bloody well would. Once the modernization of the plumbing and wiring was complete, maybe it would all settle down. Somehow he had to convince Caro of that.

Somehow he had to convince himself.

Then Caro’s phone rang.

She snatched it up off the old wooden trunk that was serving as a makeshift coffee table and looked at the display. ‘It’s Parkin!’ she said. ‘My client, the medium.’

Ollie grabbed the remote and froze the screen.

‘Hello, Kingsley,’ she answered, with relief.

Ollie watched her as she said, ‘Oh, I’m sorry. I wondered if I could speak with your partner, Kingsley. My name’s Caro Harcourt – we had lunch today – he—’

She fell silent for some moments, listening. Ollie watched her face tighten, then go pale.

‘No,’ she said. ‘No. Oh my God. No.’

She turned and stared at Ollie, looking shocked, shaking her head, then she folded her body over, pressing the phone even closer to her face. ‘Oh my God. Oh my God. I’m so sorry. I – I can’t believe it. I mean – he seemed so well. Like – this is such a shock. I’m so sorry – I’m so sorry for you – I don’t know what to say. Look – thank you for calling and telling me. I’m just so sorry. So sorry. Yes, yes, of course. It’s very good of you to have called me. Can you – can you let me know what the arrangements are, in due course. I’d like – I’d like – yes, thank you. Thank you. I’m so sorry.’

She ended the call and sat, gripping her phone in her hand and staring, white-faced, at Ollie. ‘That was Kingsley Parkin’s partner – girlfriend – whatever. She said –’ her voice was choked – ‘she said Kingsley collapsed in the street this afternoon, near the Clock Tower. That must have been just after our lunch. He was rushed to hospital – the Sussex County – but the paramedics couldn’t save him. She doesn’t know for sure yet, but it seems he had a massive heart attack.’

‘He’s dead?’ Ollie said, shocked too, and aware how feeble that sounded.

‘Dead.’ She pressed the back of her hand against her eyes, dabbing away tears. ‘Shit,’ she said. ‘Shit. I can’t believe it. He was so – so . . .’ She raised her arms in despair. ‘What the hell are we going to do now?’

Ollie looked at his watch. It was 10.15 p.m. Too late to call now. ‘I’ll call the retired vicar, Bob Manthorpe, first thing in the morning.’

‘It’s just so bloody freaky.’

‘How old was he?’

‘Not that old. I don’t know – I think he might have had a bit of work done. Around seventy, I’d guess. But he seemed so full of life.’

‘It happens,’ Ollie said. ‘I’m sure it’s a shock, but – that’s a fair age. Those old sixties rockers did their bodies in with drugs. Besides, things can happen.’

‘Sure. Straight after I had lunch with him. Things can happen all right. Don’t we bloody know it?’

‘That box of documents from your office, darling, about the house – do you remember how far back they go?’

‘They date right back to the early sixteenth century when there was a small monastic commune here, established by a group of Cistercian monks. But they then moved away up to Scotland around the early 1750s, which was when this house was built, using mostly the ruins as foundations. Why do you want to know?’

‘It was something the old chap I saw this afternoon suggested.’ He shrugged. ‘I want to go through them all, but some of them are pretty fragile, I’m worried about damaging them. Could you get some copies made at the office tomorrow?’

‘Yes – assuming we make it through the night,’ she said. Only very slightly in jest.

35

Friday, 18 September

‘Great serve! Wow, Ollie, you’re playing like a man possessed!’ his opponent at the far end of the indoor tennis court, Bruce Kaplan, called out in grudging admiration.

Kaplan rarely gave compliments. Turning forty this year, like Ollie, with a tangle of curly hair, round, wire-framed spectacles and shorts that were far too long, Kaplan looked every inch the technology boffin he was. But he played a ferocious game, moving around the court like lightning, and hating ever to lose a single point, let alone a game. They were reasonably evenly matched, although Kaplan won most of the time – just – because he was the better player, as he liked to remind Ollie. Modesty was not one of Kaplan’s handicaps.

It felt good being back on the court after a two-week absence, Ollie thought. Good to be running around, getting the physical exertion that these needle games with the American professor always became, taking every ounce of energy and concentration out of him. And good to have his mind clear, for this hour and a half on court, of absolutely everything except about where to place the ball, getting to it and firing it back, trying to outwit that arrogant whirling dervish at the far end.

But as the game progressed, he found himself drawn more and more into all the problems going around his mind, despite himself. And he kept wondering if Bob Manthorpe had called him back yet. He’d phoned him first thing this morning and left a message.

As Kaplan and he changed ends, Ollie stopped by his bag to have a swig of water and glance at his phone, on silent. No messages. It was now 1.15 p.m. and the retired vicar had not called him back. Hopefully he would sometime this afternoon.

He kept his concentration focused enough to win the first set, narrowly, on a tie-break. He lost the second 4 – 6, got whopped 0–6 on the third and was 0–3 down in the fourth when their time was finally up.

Before showering and changing, they went to the bar. Ollie ordered pints of lime and lemonade and some sandwiches for them. Then they carried them over to a table, sat and caught up on each other’s news.

‘You were doing really well in the first set,’ Kaplan said. ‘Then you kind of lost the plot. I guess it was superior play that made you realize you really didn’t have a chance, heh-heh.’

Ollie glanced at his phone and saw there was still no returned call from Manthorpe. He grinned, downed a large gulp of his drink, then wiped the back of his mouth with his hand. ‘I’ve just got a shitload of stuff on my mind at the moment,’ he said. ‘Sorry if my game was rubbish.’

‘It’s always rubbish.’

‘Sod you!’

Kaplan grinned. ‘So what’s on your mind?’

Kaplan worked in the Artificial Intelligence faculty at Brighton University. He had a number of theories that had always seemed to Ollie to be on the wild side of science, but he never dismissed anything. One of Kaplan’s interests, and the topic of a book he had written, which had been published by a respected academic imprint, was whether a computer could ever appreciate the taste of food, laugh at a joke or have an orgasm.

‘What’s your view on ghosts, Bruce?’ he asked him, suddenly.

‘Ghosts?’ the professor repeated, quizzically.

‘Do you believe they exist?’

‘Absolutely, why wouldn’t they?’

Ollie looked at him, astonished. ‘Really?’

‘I think you’ll find a lot of mathematicians and physicists – like me – believe in them.’

‘What’s your theory – I mean – what do you think they are?’

‘Well, that’s the ten-gazillion-dollar question.’ He laughed again, the short, nervous, ‘Heh-heh’ laugh he regularly made, like a nervous tic. ‘Why are you asking?’

‘I think our new house may be haunted.’

‘I can’t remember – did you say it had a tennis court?’

‘No, but there’s plenty of room for one.’

‘Going to put one in?’

‘Maybe. A lot of maybes at the moment.’

‘And you have a ghost, you think? A smart or a dumb ghost?’

‘There’s a difference?’ Ollie considered Bruce to be super-intelligent and he liked that the scientist always had an unusual – and often unique – perspective on almost any topic they ever discussed.

‘Sure! A big difference. Want to tell me about this ghost?’

Ollie told him about the bed turning round, about the spheres, the apparition that Caro and Jade had seen and all the other strange events that had happened. Kaplan listened, nodding his head constantly. When he had finished, Ollie asked him, ‘So what do you make of all that?’

Kaplan removed his towelling headband and held it up. ‘Do you know what Einstein said about energy?’

‘No.’

‘He said energy cannot be created or destroyed, it can only be changed from one form to another.’ Making a show of it, he squeezed his headband until droplets fell from it on to the white surface of the table. ‘See those droplets? That water’s been around since the beginning of time. In one form or another molecules of it might have passed through Attila the Hun’s dick when he was taking a piss, or gone over the Niagara Falls, or come out of my mother’s steam iron. Heh-heh. Every molecule in them has always existed, and always will. Boil one and it turns to steam and goes into the atmosphere; then it’ll return with a bunch of others as mist or rain one day, somewhere; it’s never going to leave our atmosphere. No energy will or can – you with me?’

‘Yes,’ Ollie said, dubiously.

‘So if you stick a knife through my heart now, killing me, you can’t kill my energy. My body will decay, but my energy will remain behind – it will go somewhere – and re-form somewhere.’

‘As a ghost?’ Ollie asked.

Kaplan shrugged. ‘I have theories about memory – I’m doing research into it right now – I think it’s a big part of consciousness. Our bodies have memory – keep doing certain movements in certain ways – certain stretches – and our bodies find them increasingly easier, right? Fold a piece of paper and the crease remains – that’s the paper’s memory. So much of what we do – and the animal kingdom does – is defined by memory. If a person spends a long time in a confined space, maybe the energy has memory, too. There’s one of the colleges at Cambridge where a grey lady was regularly seen moving across the dining hall. About fifty years ago they discovered dry rot and had to put a new floor in, raising the level about a foot. The next time the grey lady was seen, she was cut off at the knees. That’s what I mean by a dumb ghost. It’s some kind of memory within the energy that remains after someone dies – and sometimes it retains the form of that person.’

‘So what’s a smart ghost?’

‘Heh-heh. Hamlet’s father, he’s an example of a smart ghost. He was able to talk. Let not the royal bed of Denmark be a couch for luxury and damned incest. By howsoever thou pursues this act, taint not thy mind nor let thy soul contrive against thy mother aught. Leave her to heaven.’ He grinned at Ollie. ‘Yeah?’

‘So a smart ghost is basically a sentient ghost?’

‘Sentient, yes. Capable of thinking.’

‘Then the next step would be a ghost capable of actually doing something physical? Do you think that’s possible?’

‘Sure.’

Ollie stared hard at him. ‘I thought scientists like you were meant to be rational.’

‘We are.’

‘But you’re not talking about the rational, are you?’

‘You know what I really think?’ Kaplan said. ‘We humans are still at a very early stage in our evolution – and I’m not sure we’re smart enough to get much beyond where we are now before we destroy ourselves. But there’s a whole bunch of stuff waiting for us out there in the distant future if we succeed. All kinds of levels – planes – of existence we don’t even yet know how to access. Take a simple ultrasonic dog whistle as an example. Dogs can hear it but we can’t. What else is going on around us that we’re not aware of?’

‘What do you think is?’

‘I don’t know, but I want to live long enough to find out, heh-heh. Maybe ghosts aren’t ghosts at all, and it’s to do with our understanding of time. We live in linear time, right? We go from A to B to C. We wake up in the morning, get out of bed, have coffee, go to work, and so on. That’s how we perceive every day. But what if our perception is wrong? What if linear time is just a construct of our brains that we use to try to make sense of what’s going on? What if everything that ever was, still is – the past, the present and the future – and we’re trapped in one tiny part of the space–time continuum? That sometimes we get glimpses, through a twitch of the curtain, into the past, and sometimes into the future?’ He shrugged. ‘Who knows?’

Ollie frowned, trying to get his head round his friend’s argument. ‘So are you saying that the ghost in our house isn’t really a ghost at all? That we’re seeing something – or someone – in the past, who’s still there?’

‘Or maybe someone in the future. Heh-heh.’

Ollie grinned, shaking his head. ‘Jesus, you are confusing me.’

‘Go with it – sounds like you are on an amazing ride.’

‘Tell Caro that – she’s scared out of her wits. If you want to know the truth, so am I.’

‘None of us like being out of our comfort zone.’

‘We are way out of that, right now.’

Kaplan was silent for some moments. ‘This bed that you’re convinced rotated – in a space that made it impossible – yes?’

‘Yes. Either Caro and I are going mental, or the bed defied the laws of physics of the universe.’

The professor reached over and grabbed half a cheese and pickle sandwich, and bit into it hungrily. He spoke as he chewed. ‘No, there’s a much simpler explanation.’

‘Which is?’

‘It was a poltergeist.’ He grabbed the other half of the sandwich and crammed much of that into his mouth.

‘Poltergeist?’

‘Yeah. You know how poltergeists work?’

‘I’ve no idea.’

Kaplan tapped the surface of the table at which they were sitting. ‘This table’s solid, right?’

Ollie nodded.

Kaplan tapped the china plate. ‘This is solid, too?’

‘Yes.’

‘Wrong on both. Solid objects are an illusion. This plate and this table are held together by billions and billions of electrically charged sub-atomic particles all moving in different directions. They’re being bombarded, just as you and I are, by neutroni particles that pass straight through them. If something happened to change the magnetic field for an instant and, say, all the particles in the plate moved in the same direction, for just a fraction of a second, that plate would fly off the table. The same could happen to the table, making it fly off the floor.’

‘Like the Star Trek transporter?’

‘Yeah, kind of thing, heh-heh!’

‘And that’s your theory for how the bed turned round?’

‘Like I said, Ollie, we understand so little still. Go with it and accept it.’

‘Easy for you to say – you weren’t the one sleeping in the room. Want to come and spend a night in there?’