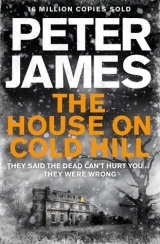

Текст книги "The House on Cold Hill"

Автор книги: Peter James

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

4

Sunday, 6 September

Jade, her long fair hair clipped back, dressed in jeans, socks and a crop top, with a note to herself written in blue ink on her left hand, was in her bedroom, which had wallpaper that she thought was a bit naff. She had spent much of this first weekend sorting her things out, with the occasional help of her mother. Her favourite song, ‘Uptown Funk’ by Bruno Mars and Mark Ronson, was blasting out from the Sonos speaker on top of a wooden chest of drawers.

It was Sunday evening and she was bored of unpacking now. Stuff lay ankle-deep on the floor, and Bombay was curled up on the patchwork quilt of her wrought-iron bed. The tortoiseshell moggie, which had adopted Jade within hours of being brought home from the rescue centre three years ago, lay contentedly amid a pile of cushions, her head resting on Blankie, the grey blanket Jade had had with her since she was an infant, and nuzzled up against Jade’s yellow, bug-eyed minion. Above the cat, Duckie, her gangly, mangy cream duck, with yellow feet and yellow bill, that she’d had almost as long as Blankie, its feet entwined in the metal latticework of the headboard, hung down gormlessly. Suspended from the other side of the headboard was her purple dream-catcher.

She’d had to admit, reluctantly, that this was a nicer room than her previous one, although it was a yucky pink. About five times larger, and – big bonus! – it had an en-suite bathroom, with a huge, old-fashioned bathtub with brass taps. She’d already luxuriated in it last night with a Lush bath-bomb, and felt like a queen.

On the curved shelves on the far side of her bedside table, she’d arranged some of her silver trophies, including her Virgin Active Brighton Tennis Club Championships, Mini Green Runner-up 2013 and Star of the Week Dance Club, 2013, along with a photograph of the rear of a pink American convertible with a surfboard sticking out of the back seat. Next to it was propped her guitar in a maroon case, alongside a music stand on which lay a curled book titled Easy Guitar Lessons. She’d already unpacked most of her books, and put them on the shelves on the opposite wall. All her sets of The Hunger Games and Harry Potter were in their correct order, as well as her collection of David Walliams, except for one, Ratburger, which was on her bedside table. Also next to it on the table were piled several books on training dogs, as well as one she loved, called Understanding Your Cat.

In front of the huge sash window was her wooden dressing table, minus its mirror which her father had not yet fixed into place. The surface was littered with cans of her body sprays, bottles of perfumes and Zoella products. Her orange plastic chair sat in front of it.

She was feeling lonely. On weekends in Brighton she would have walked round to Phoebe, Olivia or Lara’s house, or they would have come round to her, and made music videos together, or she’d have seen Ruari. Right now her parents, and her gran and gramps, were flat-out downstairs, busy unpacking boxes and getting the house in some kind of order – at least, the rooms they could live in for now, until the builders and decorators had got the house straight. Which was going to take months. Years. Forever.

The large window looked past the row of garages, over the vast rear garden and the lake, a couple of hundred yards in the distance, to the paddock, and the steep rise of the hill beyond. Her mother had told her the paddock would be perfect for the pony she had always hankered after. That brightened her a little, although she was keener at this moment on a labradoodle puppy. She’d spent a lot of time googling dog rescue centres and labradoodle breeders, and looking up all sorts of possible alternatives on Dogs 101. So far she’d found no rescue places or breeders in their area with any puppies, but there was one breeder about an hour away who was expecting a litter soon.

It was coming up to eight o’clock. No doubt one of her parents would be up soon to tell her ‘no more screen time’ and to get ready for bed. She went over to her dressing table, picked up her phone, and for some moments gazed wistfully at a video clip of Ruari, with his sharp hairstyle, nodding his head and grinning to a piece of music. Then she dialled Phoebe on her FaceTime app.

It was still light outside, despite the dark clouds and the rain, which had not relented throughout the weekend, pattering against the rattling window in front of her. ‘Uptown Funk’ was playing again at full blast. That was another plus about this new house – her room was at the far end of the first floor, with empty rooms between, so she could play her music as loudly as she liked without her parents coming in to tell her to turn it down. Mostly in their previous home she’d had to resort to wearing her headphones. At this moment she didn’t even know where the headphones were. Buried somewhere in one of the four huge boxes of her stuff that she had still not yet unpacked.

Beep, beep, beep.

The phone went dead.

‘Come on, come on!’ The internet connection here was rubbish. Her dad had promised to get it sorted tomorrow, but he was so useless at dealing with things it would probably take a week, knowing him. They were all going to have to change phone providers. God, it wasn’t like they were in the back of beyond or anything – they were only ten miles from Brighton. But at this moment, they might as well have been on the moon!

She tried again. Then, dialling for the third time, she suddenly saw Phoebe’s face filling the screen, blonde hair hanging over her forehead, and her own face in a small square in the corner.

Her friend, grinning and chewing gum, said, ‘Hey, Jade!’

Then she lost the signal, and Phoebe with it. ‘Come on, come on, come on!’ she shouted at the screen, and redialled. Moments later she was reconnected.

‘Sorry about that, Phebes!’

‘You OK?’

‘I am so not OK! I miss you tons!’

‘Me you, Jade! Mum’s in a shit mood with Dad, and taking it out on me. And all the gerbils escaped. It’s, like, not been a great day. Mungo was running around with my favourite, Julius, in her mouth, with his legs wriggling, then she shot off down the garden.’

‘Did she kill him?’

‘Dad buried him – what was left of him. I hate that cat!’

‘No! Did you get the rest of them back?’

‘They were all under the sofa in the sitting room, huddled together, looking terrified. Why would they want to escape? They had everything they needed – food, water, toys.’

‘Maybe they don’t like the weather and decided to go south for a holiday?’

Phoebe laughed. Then she said, ‘“Uptown Funk”! Turn it up!’

‘OK.’

‘What do you think – I’ve bought the latest Now CD for Lara for her birthday?’

‘Does she still have a CD player, Phebes?’

There was a long silence. Then a defensive, ‘She must have.’

‘I don’t think we have one any more.’

‘Whatever. When are you coming over?’

‘I have to negotiate an exit from here with the Cold Hill House Escape Committee. But my parents say I can have a birthday party here. Three weeks’ time! I’m going to have a retro photo booth with Polaroid cameras! And we’re going to have pizzas – everyone can order them and Dad said he’d collect them.’

‘Epic! But that’s three weeks, can I come over and see your place before then?’

‘Yes. I’ve got a great room – the biggest bath you’ve ever seen. You can almost swim in it! Can you come the weekend after next? Sleepover Saturday night? Ruari said his mum’s going to drive him over on the Sunday.’

‘Maybe we can have a swim in your pool, if it’s nice?’

‘I’ll have to get Dad to remove the dead frogs first. And fill it and heat it. That is so not going to happen.’

‘Yech!’ Then suddenly Phoebe’s voice changed. ‘Hey, Jade, who’s that?’

‘Who’s what?’

‘That woman!’

‘Woman? What woman?’

‘Er, the one right behind you? Hello!’

Jade spun round. There was no one. She turned back to the phone. ‘What woman?’

Then her phone screen went blank. Annoyed, she redialled. She heard the sound of the connection being made, and then Phoebe’s face reappeared.

‘What did you mean, Phebes? What woman?’

‘I can’t see her now, she’s gone. She was standing behind you, by the door.’

‘There wasn’t anyone!’

‘I saw her!’

Jade crossed over to the door, opened it and looked out onto the landing. She held up her phone, pointing it down the landing so Phoebe could see, then she closed the door behind her, walked back across the room and sat down again. ‘There’s no one been in, Phoebe, I’d have heard them.’

‘There was, I saw her clearly,’ her friend insisted. ‘I’m not making it up, Jade, honestly!’

Jade shuddered, feeling cold suddenly. She turned round again and stared at the closed door. ‘What – what did you see?’

‘She was, like, an old lady, in a blue dress. She had a really mean look on her face. Who is she?’

‘The only old lady here’s my Gran. She’s here with Gramps, helping unpack stuff downstairs.’ Jade shrugged. ‘They’re both a bit weird.’

Twenty minutes later, when she had ended the conversation, Jade went downstairs. Her parents were sitting at the refectory table in the kitchen, piles of unopened boxes still on the floor around them, drinking red wine, with the bottle on the table in front of them as they opened all the ‘Good Luck In Your New Home’ cards sent by friends and relatives. Sapphire was crunching dry food in a bowl close to the Aga.

‘Hi, darling,’ her mother said. ‘Are you ready for tomorrow?’

‘Sort of.’

‘Time for bed. Big day – your new school!’

Jade stared at her glumly. She was thinking about all her time at school in Brighton. She had loved being in charge of the School Walking Bus. Making the phone calls every morning, starting off with one friend, collecting another, then another, so by the time they arrived at school there were ten of them altogether. Now the rest of them would be doing this tomorrow, without her. She would be going instead to bloody St Paul’s Catholic College in Burgess Hill. Nowheresville.

And they didn’t even go to church regularly!

‘Where are Gran and Gramps?’ she asked.

‘They went home a short while ago, darling,’ her mother responded. ‘Gramps was very tired. They said to say goodbye and give you their love.’

‘Gran came up to my room.’

‘Good,’ her mother said.

‘But she didn’t say anything, and went out again. That was strange of her. She always kisses me goodbye.’

‘Were you on your computer?’

‘I was talking to Phoebe.’

‘Maybe she didn’t want to disturb you, darling.’

Jade shrugged. ‘Maybe.’

Her father looked up and frowned. But he said nothing.

5

Monday, 7 September

Monday morning came as something of a relief to Ollie. The rain had finally stopped and a brilliant, warm, late-summer sun was shining. Caro had gone to work at her office in Brighton shortly after 7.30 a.m. and at 8.00 a.m., listening to the Radio Four news, he got out Jade’s Cheerios for her breakfast, while she busied herself, first feeding the cats, then switching on the Nespresso machine, which she loved using, to make her father a coffee. Amazingly, Ollie thought, she had actually got up early this morning! But even so they were running short of time and, anxious not to be late for her first day at her new school, he gulped down his muesli, then hurried her out to the car and checked she had belted up.

As he drove, Jade, in her uniform of black jacket, yellow blouse and black pleated skirt, sat beside him in nervous silence. Neil Pringle was on Radio Sussex, talking to a Lewes artist called Tom Homewood about his latest exhibition.

‘Looking forward to your new school?’ Ollie asked.

‘LOL.’

‘What’s that meant to mean?’

‘Yeah, right. All my friends are still going to King’s in Portslade.’ She looked down at her phone. ‘St Paul’s, Burgess Hill. It sounds like a church, Dad!’

‘It seems to be a lovely school, and you know the Bartletts? Their triplets went there and loved it.’

Ollie saw her checking her phone; she was back on Instagram. At the top of the display was Jade_Harcourt_x0x0. Below she had rows and rows of thumbs-down emoticons alternating with scowly faces.

‘Listen, lovely,’ he said. ‘Give it a chance, OK?’

‘I don’t have much choice, do I?’ she said without raising her head.

He drove on in silence for some moments, then he said, ‘So your Gran came up to your room yesterday evening, but didn’t say anything?’

‘Uh-huh.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘Phebes saw her – we were FaceTiming.’

‘And your Gran didn’t say anything?’

‘No, she just went out again. Is she angry with me or something?’

‘Why should she be angry with you?’

‘Phebes said she was looking kind of grumpy.’

Ollie drove the rest of the short journey in silence, thinking, while pinging and clicking noises came from his daughter’s phone. Thinking about last night. His parents-in-law had sat with him and Caro in the kitchen. He’d given Dennis a large whisky and Pamela, who was driving as she had to these days, drank one tiny drop of red wine. They’d seen them off, Pamela telling him to say goodbye from them to Jade.

She had very definitely not gone upstairs.

6

Monday, 7 September

Arriving back home thirty minutes later, Ollie parked alongside a battered-looking red van belonging to the builders, who had arrived early and were down in the cellar, starting work on the damp. He sat for some moments, listening to Danny Pike on Radio Sussex taking a Green Party councillor in Brighton to task over a new bus lane proposal that the presenter clearly thought was absurd. He always liked Pike’s combative but informed interviewing style.

As he jumped down from the car, he caught a flash of movement to his right. It was a grey squirrel, darting up the trunk of the tall gingko tree in the centre of the circle of lawn in front of the house.

He watched the beautiful animal climb. Tree rats, Caro called them. She hated them, telling him they stripped off the bark, and, after seeing another one over the weekend, had told him to go and buy an airgun and shoot it. He watched it sit on a cross-branch and eat a nut that it held in its paws. There was no way he could shoot it. He didn’t want to kill anything here. Except maybe the rabbits, which overran the garden.

There was a smell of manure in the air, faint but distinct. Some distance above him he saw a tractor looking the size of a toy crossing the brow of Cold Hill, too far away to hear its engine. He stared around at the fields, then at the front facade of the house, still scarcely able to believe that they now lived here; this was their home, this was where, maybe, hopefully, they could actually settle, and spend the rest of their lives. Their forever home.

He pulled out his phone and took a series of photographs in all directions. He looked at the columned, covered porch, with its balustrading above, at the two sets of windows on either side of it, then up at the rows of windows on the two floors above, still struggling to orientate himself.

To the left of the front entrance was a WC, then the door to the library. To the right was the drawing room. Further along to the left there was another toilet, before the long hallway opened out into the atrium. To the left of the atrium was the huge dining room. All these rooms had high, stuccoed ceilings. Through the atrium door to the right was the kitchen and, beyond that, the downstairs part of the extension; a pantry and scullery from which the stairs ran down to the cellar with its vaulted brick ceiling. Part of the cellar housed a long-disused kitchen with a range that had not been lit in decades, once the domain of the live-in household staff. The other end of the cellar contained dusty wine racks. One day, when their finances allowed, they would stock all those racks with wine, another of their shared passions.

He’d checked out all the rooms, briefly and excitedly, on Friday, as they were moving in. God, he loved this place! He’d taken photographs of each room. Many were in a terrible state of repair and they’d have to stay that way for a long while yet. It didn’t matter; for now all they needed was to get the kitchen, drawing room and dining room straight, and one of the spare bedrooms. Their own bedroom, which had ancient red flock wallpaper, and Jade’s, were in a reasonable condition – some work had been done on them before the developers had gone bust and also before they’d moved in. The priority at the moment was the rot, the electricity and the ropy plumbing.

He stared back at the porch, and the handsome front door with its corroded brass lion’s-head knocker, and thought back, as he had several times, to that moment on Friday when he was standing there with his mother-in-law and had seen, fleetingly, that shadow. Trick of the light, or a removals man, or maybe some bird or animal – possibly the squirrel?

He went inside, through the atrium, and turned right into the kitchen. In the scullery beyond was a deep butler’s sink, a draining board and a wooden clothes-drying rack on a rope and pulley system to raise and lower it. There was also an ancient metal pump, fixed to the wall, for drawing water from the well that was supposedly under the house, but which no one had yet managed to find.

The cellar door, at the rear of the scullery, had an enormous, rusty lock on it, with a huge key, like a jailer’s. It was ajar. He went down the steep brick steps to see if the builders were OK and to tell them to help themselves to tea and coffee up in the kitchen, but they cheerily told him that they had their thermoses and were self-sufficient.

Then he climbed up the three flights of stairs to his chaotic office in the round tower on the west side of the house. It was a great space, about twenty feet in diameter, with a high ceiling, and windows giving fabulous views, one of them onto the steep, grassy slope of the hill rising out of sight. He waded through the unopened boxes and towers of files littering the floor, carefully stepping past a row of framed pictures stacked against a wall, reached his desk, and switched on his radio to Radio Sussex. As he heard the presenter grilling the Chief Executive of the Royal Sussex County Hospital over waiting times in A&E, his phone pinged with an incoming text.

It was from one of his two closest friends, Rob, asking if he fancied a long mountain bike ride round Box Hill next Sunday morning. He replied:

Sorry, mate, going to be spending time sorting out the house with Caro. And five acres of lawns to mow. Come over and see the place at the w/e.

He sent it and moments later the single-word reply pinged back.

Tosser.

He grinned. Rob and he had barely said a polite word to each other throughout their fifteen-year friendship. He sat down, retuned the radio to Radio 4, and logged on to his computer, checking his emails for anything urgent, then had a quick look at Twitter and Facebook, aware that he had not posted anything on either about the move yet. He also wanted to post some pictures of the worst dilapidations in the house on his Instagram page to show before and after. He and Caro had discussed approaching the TV show Restoration Man, but decided against because of wanting privacy.

But before any of that he had an urgent job to complete, and although the internet connection wasn’t great, it was working, sort of. His Apple Mac geek – as he jokingly referred to his computer engineer – was coming over that afternoon to try to sort it all out, but in the meantime he just had to get on with it, with an urgent deadline for a new client, the grandly titled Charles Cholmondley Classic Motors, Purveyors of Horseless Carriages to the Nobility and Gentry since 1911. They traded top-end classic and vintage sports cars, and had taken several large and very expensive stands at a classic car show that was looming up in Dubai, next month, and for next year’s Goodwood Festival of Speed. They needed an urgent revamp of their very dull and old-fashioned website.

If he got it right, it could open the door to the whole world of classic cars which he had always loved. He’d made a serious stash of cash from his previous website business, an innovative search site for people looking for properties. If he could repeat this success in the lucrative world of classic cars, they would be sorted. They’d have the money to do everything they wanted to this house.

He harboured doubts about the provenance of Charles Cholmondley Classic Motors, as the company had only been registered nine years ago. Its proprietor was a diminutive, self-important man in his fifties. On the two occasions when Ollie had met Charles Cholmondley himself, he had been flamboyantly dressed in a cream linen suit, bow tie and tasselled loafers, with silver hair that looked freshly coiffed. It was exactly the image of him that fronted the website, the dealer standing between a gleaming 1950s Bentley Continental and a Ferrari of similar vintage.

Personally, Ollie thought the message this gave off was, ‘Come and get royally screwed by me!’ He’d tried, subtly, to dissuade him from wearing the bow tie, but Cholmondley would have none of it. You have to understand, Mr Harcourt, that the people I am dealing with are very rich indeed. They like the feeling of dealing with their own kind. They see this bow tie and they see someone of distinction.

Something really did not smell right about Charles Cholmondley, and Ollie even wondered if this was his real name. But hey, he was paying good money, which at this moment he needed badly, both for this house and, if there was any surplus, to finish the restoration of his beloved Jaguar E-Type which was languishing in a lock-up in Hove until he could clear out enough space for it in one of the garages behind the house. At the moment, with all the work needed on the house, that Jag was going to be, unfortunately, a low priority.

Moments after he had settled down, Caro phoned to ask if the plumber had arrived to start work on their bathroom, and Ollie told her there’d been no sign of him yet.

‘Can you call him?’ she asked. ‘The bloody people were meant to start work at nine today.’

‘I will, darling,’ he said, trying not to sound irritated. Caro could never get her head around the fact that, although his office was based at home, he was actually working just as hard as she was. He dialled the plumber, left a message on his voicemail, then focused on his client’s website. The radio continued in the background; he listened to it all the time he was working, either Radio Sussex or Radio 4, and on Saturdays, after Saturday Live, he loved to listen to the football show, The Albion Roar, on Radio Reverb. When there was nothing on the radio he fancied, he tuned his computer to Brighton’s dedicated television station, Latest TV.

He began surfing the sites of other classic car dealers, and became frustrated, in minutes, with the slow and flaky internet connection. Several times during the next hour he shouted at the computer in anger, and wondered just how much of his life had been wasted waiting for the sodding internet. Then, at 10.30 a.m., he went downstairs to make himself a coffee.

He climbed down the steep, spiral staircase, walked a short distance along the first-floor landing, then went down the stairs to the hall, turned right and entered the oak-panelled atrium that was the anteroom to the kitchen. As he did so he saw Bombay and Sapphire both standing in the middle of the room, their hackles up, watching something.

He stopped, curious, wondering what it was. Their eyes were darting around, right then left, then up, then to the right again, in absolute synch, almost as if they were watching a movie. What were they looking at? He stood with them but could see nothing. ‘What is it, chaps?’

The cats continued to stand there, ignoring him, hackles still up, eyes still moving together, utterly absorbed.

‘What is it, chaps?’ he said again, watching them, watching their eyes. It was giving him the creeps.

Then suddenly they both howled, as if in pain, shot out of the room and disappeared along the hallway.

Deeply puzzled, he walked through into the huge kitchen. It had a low, oak-beamed ceiling, an ancient blue four-oven Aga, a twelve-seater oak refectory table which had come with the property, a pine dresser, rows of pine-fronted fitted shelves and a double sink with a large window above it looking out across the rear lawn and grounds.

He made himself a mug of latte on the Nespresso machine and carried it back into the atrium. And stopped in his tracks.

Dozens of tiny spheres of translucent white light were floating in the air, moving across the room. They ranged in size from little bigger than a pinhead to about a quarter of an inch, and all had a different density of light. They reminded him, for an instant, of living organisms he had observed through a microscope in school biology lessons. They were grouped within a narrow band, no more than a couple of feet across and rising from the floor to head height.

What on earth were they?

Was it his glasses, catching the sunlight at an odd angle? He removed them, and put them on again, and the lights had gone.

Strange, he thought, looking around. He hadn’t imagined them, surely? To his left was the long, windowless hallway leading to the front door. To his right was the small door on the far side of the atrium, which had two glass panes, and opened onto the rear terrace.

His glasses must have caught the reflection of some rays of sunlight, he decided, as he climbed back up to his office. He settled back down to work. Just as he did, Caro rang again. ‘Hi, Ols, did the new fridge turn up?’

‘No, it hasn’t turned up yet. Nor has the bloody electrician or the sodding plumber!’

‘Will you chase them?’

‘Yes, darling,’ he said, patiently. ‘The plumber called me back and is coming in an hour. I’ll chase the others.’ Caro had two secretaries at her disposal, plus a legal assistant. Why, he wondered, frustrated, did she never use them to help out?

He dutifully made the calls then returned to his work. Shortly after 1.00 p.m. he went back downstairs to make himself a sandwich. As he entered the atrium again, he felt a stream of cool air on his neck. He turned, sharply. The windows and the door to the rear garden were shut. Then he saw tiny flashes of light around him. They were a familiar precursor to the severe migraines he occasionally suffered from. They were different from the spheres he had seen earlier, but maybe those had been another manifestation of the same symptoms, he realized. He wasn’t surprised, with all the stress right now. But he didn’t have time to be ill.

He went through the kitchen into the scullery and down the stone cellar stairs. A radio at the bottom was blaring out music, and the two builders were sitting, drinking tea and eating their lunch. One was tall, in his early thirties; the other was shorter and looked close to retirement. ‘How’s it going?’ Ollie asked.

‘The damp’s pretty bad,’ the older one said, unwrapping a Mars bar and giving a sharp intake of breath. ‘You’re going to need a damp-proof membrane down here, otherwise it’s going to recur. Surprised no one ever done it.’

Ollie knew very little about building work. ‘Can you do it?’

‘We’ll get the guv to give you a quote.’

‘Good,’ he said. ‘Thank you. Might as well get it done properly. Right, well, I’ll leave you to get on with it. I’ve got to shoot out later and pick up my daughter from school. What time are you off?’

‘About five,’ the younger one said.

‘Fine – if I’m not around, just let yourselves out and shut the front door. See you tomorrow?’

‘I’m not sure,’ the older one said. ‘We’ve got an outside job and if the weather holds the guv may want us on that for a couple of days. But we’ll be back before the end of the week.’

Ollie looked at them, biting his tongue. He remembered beating their boss, Bryan Barker, down on price on the agreement that his workmen could do outside jobs as and when the weather permitted.

‘OK, thanks,’ Ollie said, and went back upstairs, swallowed two Migraleve tablets then made himself a tuna sandwich. He sat at the refectory table with a glass of water, and as he ate he flipped through the newspapers he liked to read daily, the Argus, The Times and Daily Mail, that he had picked up on his way home after dropping off Jade at school.

When he had finished his lunch he climbed back up to his office, relieved not to have developed any more migraine symptoms, so far. The tablets were doing their stuff. He stared for some minutes at a photograph of a white 1965 BMW going almost sideways, at high speed, through Graham Hill Bend at Brands Hatch. It was one of a series of images of the car, which had a strong racing pedigree, for sale on the Cholmondley website. Then he heard the front doorbell ringing. It was Chris Webb, his computer engineer, with an armful of kit, who had come to sort his internet out.

He let him in, gratefully.

A few hours later, after collecting Jade from school and returning to work, he heard Caro’s Golf scrunch to a halt on the gravel outside. Jade had long been up in her room, closeted with her mountain of homework, and Chris Webb, hunched over the Mac up in his office, was still hard at work sorting out his new connection. Chris looked up, mug of coffee in one hand, cigarette burning in the ashtray Ollie had found for him.

‘It’s the curvature of the hill that’s your problem,’ he said.

‘Curvature?’

‘There are phone masts on the top of the Downs, but the curvature of this slope effectively shields you from them. The best solution,’ Webb said, ‘would be to demolish this house and rebuild nearer the top of the hill.’

Ollie grinned. ‘Yep, well, I think we’ll have to go with another option. Plan B?’

‘I’m working on it.’

Ollie hurried downstairs to greet his wife, opening the front door for her and kissing her. Even after fourteen years of marriage, he always felt a beat of excitement when she arrived home. ‘How was your day, darling?’

‘Awful! I’ve had one of the worst Mondays of my life. Three clients in a row who’ve been gazumped on their house purchases, and one nutter.’ She was holding two large plastic bags. ‘I’ve bought a load of torches, as you suggested, and candles.’