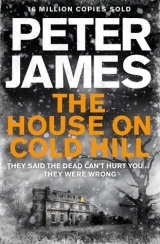

Текст книги "The House on Cold Hill"

Автор книги: Peter James

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

52

Monday, 21 September

The Monday-morning traffic into London was shit, with the M25 and then the Edgware Road clogged, and it was almost midday when Ollie finally arrived at the swanky Maida Vale premises of Charles Cholmondley Classic Motors.

As he pulled into one of the velvet-roped visitor parking bays, he stared, covetously, at the array of cars behind the tall glass wall of the showroom. A 1970s Ferrari, a Bugatti Veyron, a 1950s Bentley Continental Fastback, a 1960s Aston Martin DB4 Volante and a 1960s Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud. All of them gleamed, as spotless and immaculate as if they’d spent all their years wrapped in cotton wool and had not yet been exposed to a road.

On the way here he had managed to speak to his builder’s foreman, frustrated that his calls yesterday hadn’t been returned, and asked him, urgently, to have someone climb in through the tiny window to see what was there between the blue and yellow bedrooms, and left another voicemail for his plumber to investigate the sudden dampness of the walls in their bedroom. Then he spent twenty minutes on the phone trying to pacify Bhattacharya. He wasn’t sure he had succeeded, although the restaurateur had at least accepted the possibility of a malicious hacker – albeit one malicious to Ollie, not to himself. Someone with a grievance against Ollie, he told him. Very unfortunate, but was he willing to take the risk of someone whom Ollie had upset damaging his own business? He told Ollie he would think about it.

Seated in Cholmondley’s oak-panelled office, which was adorned with silver models of classic cars and framed photographs of exotic car advertisements from decades ago, overlooking the showroom floor, the discussion did not go so well. The car dealer himself was the very model of unctuous charm. He gave a reasoned explanation as to why he was not going to pay his bill, accompanied by expansive arm movements, and periodic flashes of his starched white double cuffs and gold links. However, he told Ollie, if he was prepared to waive this bill, in lieu of damages caused, he would be prepared to consider retaining his services going forward.

Leaving Maida Vale shortly after 1.00 p.m., having been offered neither tea, coffee nor water, Ollie was parched and starving. He’d barely eaten a thing yesterday, and he’d only managed to swallow a couple of mouthfuls of cereal for breakfast today. His nerves were jangling, his stomach felt like it was full of writhing snakes, and he was feeling light-headed from lack of sugar.

He pulled onto a garage forecourt, filled up with diesel, then bought himself a ham sandwich, a KitKat, and a Coke. He returned to his car and sat, listening to the news on the radio, while he ate.

The traffic was better than earlier but still heavy, the rain not helping, and it would be touch and go whether he made it to Jade’s school in time to pick her up. He decided to ignore the route the satnav was suggesting, which would put him outside the school ten minutes late, and short-cut his way down through Little Venice, White City and then Hammersmith, and cross the Thames there.

Suddenly his phone rang. He saw it was Bryan Barker. ‘Hi, Ollie, sorry I didn’t call you back yesterday, we’d gone over to my sister in Kent and I left my phone behind. How was your weekend?’

‘I’ve had better.’

‘Wish I could give you some good news now to cheer you up, but I’m afraid every time we look behind anything at the house, we find another problem.’

‘So what’s the latest doom and gloom?’

‘There are some nasty-looking cracks around the base of the tower, below your office – we’ve only found them since chipping away some of the rendering.’

‘What’s causing them?’

‘Well, it could just be slight movements of the earth – changes in the water table, the soil beneath drying out. Or it could be subsidence.’

‘Subsidence?’ Ollie said, knowing full well what that would entail. Cripplingly expensive underpinning. ‘Why didn’t this show up on the survey?’

‘Well, I’m looking at the relevant section of the survey now. It warned of possible movement but inspection wasn’t possible without removing some of the rendering. It says they brought this to your attention and you told them to leave it.’

‘Great!’ Ollie said, gloomily. ‘Just one thing after another after another.’

‘Should have bought yourselves a nice little brand-new bungalow if you wanted an easy life!’ Barker said.

‘Yeah, great.’ Ollie concentrated on the road for a second. He used to know this part of London well – his first job was for a small IT company down the skanky end of Ladbroke Grove, on the fringe of Notting Hill – and he cycled everywhere then. He drove along with the canal on his right.

‘Oh, and another thing,’ Barker said. ‘That window you asked us to take a look through – there’s a bit of a problem.’

‘What?’

‘I climbed up this morning – we put two ladders together – but I couldn’t see in – there are metal bars blocking out the light.’

‘Metal bars? Like a prison cell?’

‘Exactly.’

‘So is it a room?’

‘I don’t know – we’d either have to cut away the bars or go in through a wall.’

‘How long are you going to be there today, Bryan?’

‘I’ve got to leave early today – I’ve got a site visit to make, and it’s Jasmin’s birthday – I’ll be in big trouble if I’m late!’

‘I’ve asked the plumber, but if you have time could you also take a look in our bedroom? I think we may have a serious damp problem there.’

‘OK – and you’ll be at the house in the morning?’

‘Yes, I’ll be working from home all day.’

Ollie ended the call and drove on, immersed in his thoughts. At least he had a resolution, of a kind, with Cholmondley. He was going to have to accept the bastard’s deal, he knew, because it was still a gateway to other classic car dealers. And he had a lot of damage limitation ahead with the other dealers who’d been copied in on the vile email that had gone to Cholmondley. With luck, Bhattacharya could be salvaged. And tonight the vicar and Benedict Cutler were coming.

He had a good feeling about that.

Fortinbrass seemed a very human man, concerned and interested. He and Benedict Cutler would help them clear whatever malevolence was in the house. It was 2015, for God’s sake. Ghosts might have terrified people in past centuries, but not any more. This evening was high noon for any spectral guests at Cold Hill House.

The thought made him smile. He was nearing Gatwick airport on the M23, in heavy rain, and was only about twenty-five minutes now from Jade’s school. He would get there with a good ten minutes or more to spare. He leaned forward and switched channels to Radio Sussex. He liked listening to the Alison Ferns afternoon show.

The three o’clock news came on and he turned the volume up a little. The announcer, in his sombre, clear, unemotional BBC voice, stated there was more controversy over the wildcat French industrial action in Calais causing further Eurostar cancellations. There were fresh airstrikes against an ISIS stronghold. A family doctor was questioning the effectiveness of flu vaccinations. Then, suddenly, Ollie stiffened as he heard:

‘Two people who died today when their Volkswagen Golf was in a head-on collision with a lorry, on the B2112 Haywards Heath to Ardingly road, were named as Brighton solicitor Caroline Harcourt and her daughter Jade.’

53

Monday, 21 September

Ollie swerved off onto the hard shoulder and slammed on his brakes, switching on the hazard lights, the wipers clouting away the raindrops. He sat for a moment, drenched in perspiration, his entire body pounding. The Range Rover rocked in the slipstream of a lorry that thundered past, too close, inches away from his wing mirror, as he stabbed Caro’s direct line on his speed-dial button.

It rang once, twice, three times.

‘Answer, please answer, please, please, please, darling.’

Then, with an immense surge of relief, he heard her voice, the professional tone she always adopted when at work. ‘Hi, Ols, I’m with a client at the moment – can I call you back in a while?’

‘You’re OK?’ he gasped.

‘Yes, thank you very much. I’ll be about half an hour.’

‘Jade’s not with you?’

‘I thought you were picking her up from school?’

‘Yes – yes – yes, I am. Call me when you can.’

Another lorry rocked the car.

Had he imagined it?

He must have. Unless, he thought with growing terror, it was another time-slip. Something he had seen that had not yet happened? More evidence that he was going insane?

But he wouldn’t let Caro drive the Golf, nor take Jade anywhere, not for a few days, not until he was absolutely certain he’d just imagined this.

He checked his mirror, accelerated and pulled out onto the inside lane. He was still shaking uncontrollably, perspiration running down the back of his neck.

He didn’t calm down until he saw Jade trotting out of the school gates, rucksack on her back, cheerily chatting with a group of friends. She headed over towards him and climbed up into the car.

‘How was your day, lovely?’

She shrugged, pulling on her seat belt. ‘Mr Simpson was really annoying.’

‘Your music teacher? I thought you liked him.’

She shrugged again. ‘I do, but he can be sooooooo annoying!’

He smiled. But, inside him, a storm was still raging.

When they arrived home shortly before 4.00 p.m., the rain had eased to a light drizzle. The only trade vehicle parked outside the house was the plumber’s black van. As Jade went up to her room, Michael Maguire came out of the kitchen, his face grimy.

‘Ah, Lord Harcourt!’ he greeted him.

‘What did you discover about the bedroom walls, Mike?’

Maguire shook his head. ‘A mystery.’

‘But they’re damp, right? Where’s it coming from – upstairs again?’

‘They’re hardly damp – a tiny bit, I suppose – enough to loosen the old wallpaper paste.’

‘A tiny bit? They were sopping wet last night. We had to move down to the drawing room and sleep on the sofas.’

The plumber shook his head again, looking baffled. ‘We’ll go up there, if you like?’

Ollie followed him up the stairs, and into their bedroom. He went over to each wall in turn, laying the palm of his hand flat against the paper, and across to where the strips had fallen. Maguire was right. The walls felt almost bone dry. ‘I don’t understand – they were sopping in the middle of the night. They can’t just have dried out, it’s been raining all day.’

‘I spoke to Bryan Barker earlier,’ Maguire said. ‘He’s got a meter for measuring damp, and we’ll do some checks tomorrow if I get time. Got a busy day – the new boiler’s arriving first thing. You won’t have any hot water for a few hours, but I’ll make sure it’s all up and running by the evening.’

‘Do you have a sledgehammer?’ Ollie asked, suddenly.

‘A sledgehammer?’ Maguire looked surprised.

‘Yes.’

‘Planning to crack a nut, are you?’

‘Something like that.’ Ollie gave him a weak smile.

‘I’ve seen one lying around . . .’ The plumber frowned, pensively. ‘I think there’s one down in the cellar.’

‘Great, thanks.’

Ollie stared around at the two bare patches of wall which the paper had fallen from, and several other places where it had begun to peel. He walked around the room as he had done in the middle of the night, placing the palm of his hand against the wall.

Maguire was right. The dampness of the middle of the night had gone.

How?

But he had a bigger worry at this moment. He perched on the edge of the bed, pulled out his phone and went to the Argus online, which carried the latest Sussex newsfeeds. He searched down through them for Traffic. There was a three-car accident on the A27 at Southwick which had happened an hour ago. A pedestrian was in critical condition after being struck by a van near the Clock Tower in central Brighton at midday. An elderly man had been cut out of an overturned car at the Gatwick intersection of the A23 earlier in the day.

No fatalities.

No mother and daughter in a collision with a lorry.

His mind playing with him again?

Or a deadly time-slip?

The two cats, Bombay and Sapphire, came into the room, and both in turn nuzzled against him.

He stroked them for some moments, changed out of his business suit into jeans, a sweatshirt and trainers, then went back downstairs and into the kitchen, feeling badly in need of a drink.

He had always tried to make it a rule, apart from the occasional glass with lunch, never to have a drink before 6.00 p.m. But today he grabbed a bottle of Famous Grouse from the kitchen shelf, twisted off the cap, and necked a gulp straight from the bottle. Its fiery warmth sliding down his throat and into his belly instantly made him feel a little more positive. He took a second swig, replaced the cap and put the bottle back on the shelf. Then he went down into the cellar.

Barker’s workers had been busy here. Huge chunks of wall had been knocked out, exposing raw red brick, supported in several places by steel Acrow props. Lying by one wall was a large metal tool box, next to which was an angle grinder, a power drill, and, on the floor, a sledgehammer with a long wooden handle.

He lifted the heavy tool and carried it up, through the kitchen, and on up to the first-floor landing. Music was, as ever, coming out of Jade’s bedroom door.

Good, he thought. Hopefully, she wouldn’t hear him – or would assume it was the builders.

He entered the blue bedroom, walked straight over to the right-hand wall, and swung the sledgehammer hard against it. It struck with a dull thud, making a tiny indent, and throwing up a small shower of plaster. He swung it again in the same place. Then again. Again. The indent slowly grew larger.

Suddenly the head of the hammer embedded itself into the wall. He pulled it back and swung it again, exposing raw red brick. As he did so, he became aware of someone standing behind him in the room.

He turned.

There was no one.

‘Just fuck off!’ he shouted, then swung again, again, again, the hole in the wall steadily getting larger, more and more pieces of brick crumbling and falling onto the floor.

Finally, after ten minutes, sodden with perspiration, and out of breath again, another chunk of the wall fell away, and the hole was just about big enough to crawl through.

He stepped closer to it, his heart thudding, knelt and peered through. There was a stale smell, of old wood and damp. But the light was so dim he could barely see anything. He switched on the torch app on his phone and shone the beam inside.

A shiver ripped through him.

It was a tiny room, no more than six feet wide. Another spare bedroom – once?

Except it was completely bare.

Apart from what was on the far wall.

More shivers rippled through him.

Shit. No. No.

A pair of manacles, on the end of short lengths of rusty chain, were bolted to the wall. Protruding from each manacle were bones – part of what once would have been a hand and wrist. Several fingers were held together by black sinews, but most were missing.

And he could see where they were.

They lay scattered on the floor, along with the skull and all the other bones of the person who had once been imprisoned here. Also on the floor were the decayed remains of a blue dress, other strips of clothing, a pair of yellow silk slippers with tarnished gold buckles and a dusty fan.

He stared, shaking with shock, unsteady on his legs. Stared at the skull. At the scattered bones. He could make out legs, arms, ribcage. He stared at the grinning skull again.

He felt as if a current of electricity was running through him. It seemed as if every hair on his body was standing on end, and that a hundred tiny, ragged fingernails were plucking at his skin.

Then he felt a sharp prod in the small of his back.

54

Monday, 21 September

‘SHIT!’ he screamed, cracking his head on the top of the hole as he jumped backwards.

And saw his daughter right behind him.

‘Sheesh! You scared the hell out of me, Jade!’

‘What are you doing, Dad?’

‘I’m – I’m – just tracing the wiring in the house.’

‘Can I have a look?’

‘There’s nothing there. Go back to your homework, lovely. I’m sorry if I disturbed you.’ He put an arm round her and hugged her tiny frame. After the shock he’d had driving this afternoon it felt so good to feel her, smell her, hear her sweet, innocent voice.

Just to know she was alive.

‘I’m doing some geography stuff, Dad. What do you know about tectonic plates?’

‘Probably less than you do! Why?’

‘Stuff I have to do.’

‘They shift, apparently.’

‘Can we go to Iceland? You can see a join there! You can walk along it, I was reading about it and saw some cool pictures!’

‘Iceland? Sure. When do you want to go – in half an hour?’

‘You know, Dad, sometimes you’re just so – so – so annoying.’

Ollie waited until she had gone back out of the room. Shaking again, it took him several minutes before he plucked up the courage to look back through the hole. He shone the beam down on the skull. Was this Lady De Glossope – formerly Matilda Warre-Spence?

Had he finally cracked the mystery of her disappearance two and a half centuries ago?

Had her husband done this to her? Used her money, manacled her to this wall, then bricked in the entrance and left her to die and rot, while he went gallivanting off across the world with his mistress?

Was this the reason why Sir Brangwyn De Glossope had shut the house down for three years? To give time for the stench of her decomposing body to fade? To give time for the rats to feast on her and conveniently dispose of her remains?

Was it her ghost, or spirit, or whatever it was, that was so angry, and causing all the problems here? Had she cursed this place?

He felt the sensation of an electric current running through him again. His skin felt as if it were being pinched in, then released, again and again. He sensed the presence of someone behind him, and spun round. Stared at the empty room. Felt someone grinning at him. He staggered away from the hole, reeling with shock. Jesus, he thought. Jesus. This had been in the house with them all the time.

What the hell was he going to say to Caro? How on earth could he tell her this?

Hopefully, in less than two hours, when the clergymen arrived, they would find out just what was really going on here.

He should call the police, he knew, but after their last visit, that worried him.

He went out onto the landing and slammed the door shut, then stood there for some moments, trembling. Oh shit, oh shit, oh shit.

He went down into the kitchen, sat at the refectory table and shaking uncontrollably, began flicking through the glossy pages of Sussex Life magazine, which must have arrived with the morning’s papers, to try to calm himself down.

He looked at some pages of estate agency particulars of grand country houses – each one described with estate agency hyperbole. Descriptions that could apply to Cold Hill House.

A very well-presented period property in need of some modernization.

A beautiful, detached family house on the periphery of a village in stunning countryside.

A spectacular country home, boasting a wealth of exposed timbers.

A striking Georgian manor.

Did they all have ghosts, too?

Spectral residents on a mission to screw up the lives of their occupants?

A shadow moved in front of him.

He looked up, startled. Then his eyes widened in relief. It was Caro.

‘Darling!’ he said, jumping up. ‘You’re home early!’

‘Didn’t you get my message?’

‘Message?’

‘I phoned you back but you didn’t answer. And I texted you. My last client of the day cancelled, so I thought I’d come home early.’ She gave him a vulnerable smile. ‘You know, get ready for our visitors. Tidy up a bit, get some nice biscuits out. So how did your meeting go?’

‘Yes, OK,’ he said.

‘Worth the journey?’

‘Apart from coming back with car-envy. You should see his showroom – it’s incredible. I was drooling at some of the cars in there.’

‘I’m afraid you’re going to have to keep drooling for a while yet. How’s everything here?’

‘Oh, you know, fine.’ He was thinking how to break the news about the skeleton upstairs – without totally freaking her out.

‘I’ll go up and see Jade – how was her day at school?’

‘OK. But not very happy with her music teacher today.’

‘I thought she really liked him.’

‘So did I.’

Caro paused for a moment, then she said, ‘So where are we going to meet Mr Ghostbuster and his mate? In here or in the drawing room?’

‘I think in here,’ Ollie replied. ‘It’s warmer for a start – unless you want me to light a fire?’

‘Here’s fine,’ she said. Then she peered at him. ‘You’re covered in dust – what have you been doing?’

‘Oh – I was down in the basement earlier with the builders,’ he said.

‘Are you feeling OK, Ols?’

‘OK?’

‘Yes.’

‘I’m fine.’

‘You don’t look OK.’

Nor would you if you’d just hacked through a wall and found a manacled skeleton, he nearly said. Instead he replied, ‘I’m just looking forward to these guys coming. I’ve got a good feeling about them.’ He was thinking that perhaps he could use them to help soften the shock of the skeleton to Caro.

‘I wish I shared your optimism,’ she said bleakly. ‘I don’t have a good feeling about anything at this moment. I’m going to change. I think you should too, you look like you’ve just come off a building site.’

‘I have!’

‘Yes, well, I think it might be respectful to look a little smarter, OK?’

‘It’s all going to be fine, darling. It will be.’

Caro said nothing for some moments then she said, ‘I don’t think we should stay here for a bit, Ols. Mum said we could stay there until the damp and stuff is sorted. Why don’t we do that? We can’t go on like this here.’

Ollie had memories of staying with his in-laws for several months, five years ago, while renovation work was happening to their Carlisle Road house. After about three days he had been ready to murder his father-in-law and after five days his mother-in-law, too.

‘Things are being sorted, Caro.’

‘Good, well, when they are sorted, we can move back in.’

‘I need to be here on site to manage all the workmen.’

‘Fine, you can commute. We can stay in Mum and Dad’s basement – Jade can have her own room. At least we’ll be safe – and dry.’

And insane, Ollie thought. ‘Shall we see how we feel after the vicar and the minister have been?’

‘OK,’ she said, reluctantly. ‘But I’m not totally convinced. They might be able to clear ghosts, but I doubt they’ll know much about putting in damp-proof courses and stopping wallpaper from falling down.’

‘Well, if God can part the Red Sea, I wouldn’t have thought a spot of damp would cause Him too much of a problem,’ Ollie said and grinned.

She gave a faint smile. ‘Let’s see.’

Feeling a little more confident with Caro home, Ollie went upstairs, washed the dust off his face and brushed it out of his hair, and changed into clean clothes. Then he went up to his office to deal with his emails until the two clergymen turned up – they were due in an hour and a half. He sat down at his computer and logged on, worried about what he was going to find next.

Suddenly his iPhone pinged with a text message. He looked down and saw the words:

TWEEDLEDUM AND TWEEDLEDEE ARE ON THEIR WAY! THAT’S

WHAT YOU THINK. THEY’RE DEAD. YOU ALL ARE.

And, as before, a second later the words vanished.