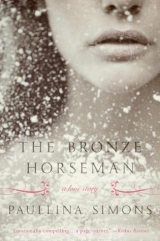

Текст книги "The Bronze Horseman"

Автор книги: Paullina Simons

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 47 страниц)

But what Tatiana felt for Alexander was true.

What Tatiana felt for Alexander was impervious to the drumbeat of conscience.

Oh, to be walking through Leningrad white night after white night, the dawn and the dusk all smelting together like platinum ore, Tatiana thought, turning away to the wall, again to the wall, to the wall, as ever. Alexander, my nights, my days, my every thought. You will fall away from me in just a while, won’t you, and I’ll be whole again, and I will go on and feel for someone else, the way everyone does.

But my innocence is forever gone.

12

Two days later, on the second Sunday in July, Alexander and Dimitri, dressed in their civilian clothes, called on Tatiana and Dasha. Alexander wore black linen trousers and a white cotton button-down short-sleeved shirt. Tatiana had never seen him in a short-sleeved shirt before, seen skin beyond his face and hands. His forearms were muscular and tanned. His face was clean-shaven. She had never seen him clean-shaven. By the time the evening hour fell, Alexander always had stubble. Tatiana thought, her heart catching on him, that he looked almost impossibly handsome.

“Where do you girls want to go? Let’s go somewhere special,” said Dimitri. “Let’s go to Peterhof.”

They packed some food and went to catch the train from Warsaw Station. Peterhof was an hour’s train ride away. All four of them walked a block along Obvodnoy Canal, where Alexander and Tatiana ambled every day. Tatiana walked in silence. Once when Alexander jumped off the narrow pavement and strolled ahead of her with Dasha, his bare arm brushed against her bare arm.

On the train Dasha said, “Tania, tell Dima and Alex what you call Peterhof. Tell them.”

Tatiana came out of her thoughts. “What? Oh. I call it the Versailles of the Soviet Union.”

Dasha said, “When Tania was younger, she wanted to be a queen and live in the Great Palace, didn’t you, Tanechka?”

“Hmm.”

“What did the kids in Luga used to call you?”

“Can’t remember, Dasha.”

“No, they called you something so funny. The queen of… the queen of…”

Tatiana glanced at Alexander, who glanced at Tatiana.

“Tania,” asked Dimitri, “what would have been your first act as queen?”

“To restore peace to the monarchy,” she said. “And then to behead all transgressors.”

Everybody laughed. Dimitri said, “I really missed you, Tania.” Alexander stopped laughing and stared out the window. Tatiana, too, stared out the window. They were sitting diagonally across from each other on facing seats.

Touching her neat ponytail, Dimitri said, “Tania, why don’t you ever wear your hair down? I saw it down once. It looked so pretty.”

Dismissively Dasha said, “Dima, forget it, she’s so stubborn. We tell her and tell her. Why do you keep it so long if you don’t do something with it? But no. She never wears it down, do you, Tania?”

“No, Dasha,” said Tatiana, wishing for her wall, for anything, just so her flushed face would not be in view of Alexander’s quietly full eyes.

“Take it out of your ponytail now, Tanechka,” said Dimitri. “Go on.”

“Go on, Tania,” said Dasha.

Slowly Tatiana pulled the rubber band out of her hair and turned to the window, not speaking again until their stop.

In Peterhof they did not take an organized tour but meandered around the palace and the Elysian manicured grounds instead, finally finding a secluded spot on the lawn under the trees near the Great Cascade Fountain to have their picnic.

With gusto they ate their lunch of hard-boiled eggs and bread and cheese. Dasha had even brought vodka, and she and Alexander and Dimitri drank from the bottle, while Tatiana refused. Then everybody had a smoke except Tatiana.

“Tania,” Dimitri said, “you don’t smoke, you don’t drink. What do you do?”

“Cartwheels!” exclaimed Dasha. “Right, Tania? In Luga, Tania taught all the boys how to do cartwheels.”

“All the boys?” said Alexander.

“Yes, yes,” echoed Dimitri. “There were boys in Luga?”

“Like flies around Tania.”

“What are you talking about, Dasha?” Tatiana said, suddenly embarrassed. With an effort, she did not meet Alexander’s eyes.

Dasha pinched Tatiana on the thigh. “Tania, tell Dima and Alex how those wild beasts never left you alone.” She laughed. “You were like honey to bears.”

“Yes, tell us, Tania!” said Dimitri.

Alexander said nothing.

Tatiana was beet red. “Dasha, I was maybe seven. There was a group of us. Boys and girls.”

“Yes, and they all buzzed around you,” Dasha drew out, looking fondly at Tatiana. “Our Tania was the cutest child. She had round button eyes and those little freckles and not just blonde but white-blonde hair! She was like a ball of white sunshine rolling around Luga. None of the old ladies could keep their hands off her.”

“Just the old ladies?” Alexander asked evenly.

“Do a cartwheel, Tania,” said Dimitri with his hand on her back. “Show us what you can do.”

“Yes, Tania!” Dasha said. “Come on. This is the perfect place for it, don’t you think? Here in front of a majestic palace, fountains, lawn, gardenias blooming—”

“Germans in Minsk,” said Tatiana, trying not to look at Alexander, lying on the blanket on his side, propped up by his elbow. He looked so casual, so familiar, so…

And yet, at the same time, utterly untouchable and unattainable.

“Forget the Germans,” Dimitri said. “This is the place for love.”

That’s what Tatiana was afraid of.

“Come on, Tania,” Alexander said softly, sitting up and crossing his legs. “Let’s see these famous cartwheels.” He lit a cigarette.

Dasha prodded her. “You never say no to a cartwheel.”

Tatiana wanted to say no today.

Sighing, she got up from their old blanket. “Fine. Though, frankly, I don’t know what kind of a queen I’d make, doing cartwheels for my subjects.”

Tatiana was wearing a dress, not the dress but a casual pink sundress. Walking a few meters away from them, she said, “Are you ready?” And from a distance she saw Alexander’s eyes swallowing her. “Watch,” she said, putting her right foot forward. She flung herself upside down on her right arm, swinging her body in a perfect arc around onto her left arm and then her left foot, and then, without taking a breath and with her hair flying, Tatiana whirled around again, and again and again in an empyrean circle, down a straight trajectory on the grass toward the Great Palace, toward childhood and innocence, away from Dimitri and Dasha and Alexander.

As she walked back, her face flushed and her hair everywhere, she allowed herself a glance at Alexander’s face. Everything she had wanted to see was there.

Laughing, Dasha fell on top of Alexander and said, “What did I tell you? She’s got hidden talents.”

Tatiana lowered her gaze and sat down on the blanket.

Rubbing Tatiana’s back, Dimitri said, “Hmm, Tania, what else do you have in your bag of tricks?”

“That’s it,” she replied tersely.

A little later, Dimitri asked, “Dasha, Tania, how would you girls define love?”

“What?”

“How would you define love? What does love mean to you?”

“Dima! Who wants to know?” Dasha smiled at Alexander.

“It’s just a question, Dasha.” Dimitri drank some more vodka. “This is a good place, a fine Sunday, for that question.” He smiled at Tatiana.

“I don’t know. Alexander, should I answer it?” Dasha asked.

Shrugging and smoking, Alexander said, “Answer if you want.”

The blanket was too small for the four of them, Tatiana thought. She was sitting in a lotus position, Dima was lying on his stomach to her left, and Alexander and Dasha were in front of her, Dasha leaning into Alexander.

“All right. Love… let’s see,” said Dasha. “Help me out, Tania, will you?”

“Dash, you can do this. I know you can.” Tatiana didn’t want to say that Dasha had had lots of field experience.

“Hmm… love. Love is… when he comes by when he says he’s going to,” she said, nudging Alexander. “Love is when he is late but says he is sorry.” She smiled. “Love is when he doesn’t look at any other girls but me.” Nudging him again, twice. “How’s that?”

“Very good, Dasha,” said Alexander.

Tatiana coughed.

“Tania! What? You’re not satisfied with that?” Dasha asked.

“No, no. It’s very good.” But the teasing hesitation was clearly in her voice.

“What, clever clogs? What didn’t I say?”

“Oh, no, Dash. Everything. But it sounds to me what you described is what it’s like to be loved.” She paused. No one else spoke. “Isn’t love what you give him, not what he gives you? Is there a difference? Am I completely wrong?”

“Completely,” said Dasha, smiling at Tatiana. “What do you know?”

“Nothing,” Tatiana said, not looking at anyone.

“Tanechka?” said Dimitri. “What do you think love is?”

Tatiana felt she was being set up.

“Tania? Tell us. What does love mean to you?” Dimitri repeated.

“Yes, go ahead, Tania,” said Dasha. “Tell Dimitri what love means to you.” And then in a teasing, affectionate voice, she said, “To Tania, let’s see, love is being left alone for a whole summer to read in peace. Love is—sleeping late, that’s the number one love. Love is—crème brûlée ice cream; no, that is the number one love. Tania, tell the truth, if you could sleep late all summer, and read while you ate ice cream all day, tell me you would not be in bliss!” Dasha laughed. “Love is, oh, I know—Deda! He is number one. Love is this Great Palace. Love is telling us those silly jokes, trying to make us laugh. Love is, Pasha—he is definitely number one. Love is—oh! Naked cartwheels!” Dasha exclaimed with joy.

“Naked cartwheels?” asked Alexander, who had not taken his eyes off Tatiana.

Dimitri said, “Can we see those?”

“Oh, Tania! They should see how you do those cartwheels! At Lake Ilmen she would catapult herself naked five times right into the water.” Delight was all over Dasha’s face. “Wait! That’s it! That’s what you were called. The kids used to call you the cartwheel queen of Lake Ilmen!”

“Yes,” said Tatiana calmly. “Not the naked cartwheel queen of Lake Ilmen.”

Alexander was trying not to laugh.

Dasha and Dimitri were rolling on the blanket.

Throwing a piece of bread at her sister, all red in the face, Tatiana said, “I was seven then, Dashka.”

“You’re seven now.”

“Shut up.”

Dasha knocked Tatiana back, throwing herself on top of her, “Tania, Tania, Tania,” she squealed, tickling Tatiana. “You’re the funniest girl.” And when she was very close to Tatiana’s face, she said, “Look at all your freckles.” Dasha bent her head and kissed them. “They’ve really popped out. You must be walking outside a lot. You don’t walk home from Kirov, do you?”

“No, and get off me. You are way too heavy,” said Tatiana, tickling her sister back and pushing her off.

Dimitri said, “Tania, you didn’t answer the question.”

“Yes,” said Alexander. “Let Tatiana answer the question.”

It took Tatiana a few moments to get her breath back. Finally she said, “Love is…” And with a pulsing heart she thought about what she could say and what would be a big lie. What would be the truth? Partial truth, whole truth? How much could she give right now? Knowing who was listening. “Love is,” she repeated slowly, looking only at Dasha, “when he is hungry and you feed him. Love is knowing when he is hungry.”

Dasha said, “But, Tania, you don’t know how to cook! He’d pretty much starve, wouldn’t he?”

Dimitri cackled. “What about when he is horny? What do you do then?” He laughed so hard he started hiccuping. “Is love knowing when he is horny? And feeding him?”

“Shut the hell up, Dimitri,” said Alexander.

“Dima, you are just so crass,” said Dasha. “You have no class.” Turning to Alexander and smiling, she pushed him lightly and said in an eager voice, “All right, now your turn.”

Tatiana, sitting motionless in her lotus position, looked beyond Alexander to the Great Palace, thinking of the gilded throne room and all her dreams blossoming here in Peterhof when she was a child.

“Love is, to be loved,” said Alexander, “in return.”

Her lower lip trembling, Tatiana would not take her eyes off Peter the Great’s Summer Palace.

Dasha leaned into him with a smile. “That’s nice, Alexander.”

Only when they all got up and folded their blanket to catch the train back did it occur to Tatiana that no one had asked Dimitri what love meant to him.

That night, as she was turned to the wall, remorse over Alexander ate Tatiana up from the whites of her bones. To turn away from Dasha like this was to admit the unadmittable, to accept the unacceptable, to forgive the unforgivable. Turning away meant that deception was going to become her way of life, as long as she had a dark wall to turn her face to.

How could Tatiana live a life, breathe in a life where she could sleep next to her sister with her back turned every night? Her sister, who took her mushroom picking in Luga a dozen years ago with only a basket, no knife and no paper bag, “so that the mushrooms wouldn’t be afraid,” Dasha had said. Her sister, who taught Tatiana how to tie her shoelaces at five and to ride her bike at six, and to eat clover. Her sister, who looked after her summer after summer, who covered for all her pranks, who cooked for her and braided her hair and bathed her when she was small. Her sister, who had once taken her out at night with her and her wild beaus, letting Tatiana see how young men behaved with young women. Tatiana had stood awkwardly against the wall of Nevsky Prospekt, eating her ice cream, while the older boys kissed the older girls. Dasha never took Tatiana with her again and after that night became more protective of Tatiana than ever.

Tatiana could not continue like this one more day.

She had to ask Alexander to stop coming to Kirov.

Tatiana felt one way. That was indisputable. But she had to behave another way. That was indisputable, too.

Turning away from the wall and to Dasha, Tatiana reached out and gently stroked the length of her sister’s thick curls.

“That feels nice, Tanechka,” murmured Dasha.

“I love you, Dasha,” said Tatiana, as her tears trickled down on the pillow.

“Mmm, love you, too. Go to sleep.”

All the while her mind was laying down the unassailable law of right and wrong, Tatiana’s breath was whispering his name in the rhythmic beat of her heart. SHU-rah, SHU-rah, SHU-rah.

13

On the Monday after Peterhof, when a smiling Alexander met an unsmiling Tatiana at Kirov, she said to him before even a hello, “Alexander, you can’t come anymore.”

He stopped smiling and stood silently in front of her, at last prodding her with his hand. “Come on,” he said. “Let’s walk.”

They walked the long block to Govorova.

“What’s the matter?” He was looking at the ground.

“Alexander, I can’t do this anymore. I just can’t.”

He stayed quiet.

“I can’t make it,” said Tatiana, strengthened by the concrete pavement under her feet. She was glad they were walking and she didn’t have to look at his face. “It’s too hard for me.”

“Why?” he asked.

“Why?” Flummoxed by that question, she fell silent. Not one of her answers could she speak aloud.

“We’re just friends, Tania, right?” Alexander said quietly. “Good friends. I come because I know you’re tired. You’ve had a long day, you have a long way home, and a long evening ahead of you still. I come because sometimes you smile when you’re with me, and I think you are happy. Am I wrong? That’s why I come. It’s not a big thing.”

“Alexander!” she exclaimed. “Yes, we have the pretense of not really being up to much. But please.” She took a breath. “Why don’t we tell Dasha then that you take me home from Kirov? Why do we get off every single day three blocks before my building?”

Slowly he said, “Dasha wouldn’t understand. It would hurt her feelings.”

“Of course it would. It should!”

“But, Tania, this has nothing to do with Dasha.”

Tatiana’s efforts to remain calm were costing her white fingers blood. “Alexander, this has everything to do with Dasha. I can’t lie in bed with her night after night, afraid. Please,” she said.

They came to the tram stop. Alexander stood in front of her. “Tania, look at me.”

She turned her head away. “No.”

“Look at me,” he said, taking both her hands in his.

She raised her eyes to Alexander. His big hands felt so comforting.

“Tatia, look at me and say, Alexander, I don’t want you to come anymore.”

“Alexander,” she said in a whisper, “I don’t want you to come anymore.”

He did not let go of her hands, nor did she pull away.

“After yesterday you don’t want me to come anymore?” he asked, his voice faltering.

Tatiana could not look at him when she spoke. “After yesterday most of all.”

“Tania!” he exclaimed suddenly. “Let’s tell her!”

“What?” She thought she had misheard.

“Yes! Let’s tell her.”

“Tell her what?” Tatiana said, her tongue suddenly full of frozen fear. She shivered in her sleeveless top. “There is nothing to tell her.”

“Tatiana, please!” Alexander’s eyes flashed at her. “Let’s tell the truth and live with the consequences. Let’s do the honest thing. She deserves that. I’m going to end it with her and then—”

“No!” She tried to pull her hands away. “Please, no. Please. She’ll be devastated.” She paused. “We have to think about other people.”

“What about us?” He squeezed her hands. “Tania…” he whispered, “what about you and me?”

“Alexander!” Her nerves were raw. “Please…”

“You please!” he said loudly. “I’m sick to death of this—all because you don’t want to do the honorable thing.”

“When is it honorable to hurt other people?”

“Dasha will get over it.”

“Will Dimitri?”

When Alexander did not reply, Tatiana repeated, “Will Dimitri?”

“Let me worry about Dimitri, all right?”

“And you’re wrong. Dasha will not get over you. She thinks you’re the love of her life.”

“She thinks wrong. She doesn’t even know me.”

Tatiana couldn’t listen anymore. She yanked her hands away. “No, no. Stop talking.”

Alexander stood in front of her on the pavement. “I’m a soldier in the Red Army. I’m not a doctor in America. I’m not a scientist in Britain. I’m a soldier in the Soviet Union. I could die any minute a thousand different ways to Sunday. This might be the last minute we will have together. Don’t you want to spend that minute with me?”

Mesmerized by him, Tatiana muttered, “Right now, I just want to crawl into bed—”

“Yes,” he exclaimed fervently, “crawl into bed with me!”

Weakening, Tatiana shook her head. “We have nowhere to go…” she whispered.

Alexander came up close and cupped her face as he said in a trembling, encouraged voice, “We’ll work it out, Tatiasha, I promise, somehow we’ll—”

“No!” she cried.

His hands lowered.

“You… misunderstood,” she stammered. “I meant that there is nothing for us to do.”

And then his eyes lowered.

And hers, too. “She is my sister,” Tatiana said. “Why can’t you just understand? I will not break my sister’s heart.”

Alexander took a step back and said coldly, “Oh, that’s right, you already told me. There will be other boys. But never another sister.” Without another word he turned around and began walking away.

Tatiana ran after him. “Alexander, wait!”

He kept walking.

Tatiana could not keep up. “Please, wait!” she called into Ulitsa Govorova. She held on to the wall of a yellow stucco building, whispering, “please come back.”

Alexander came back. “Let’s go,” he said flatly. “I have to get back to the barracks.”

Tatiana persisted. “Listen to me. If we stop now, at least there will be nothing to tell the people who are close to us, who love us, who depend on us not to betray them. Dasha—”

“Tatiana!” Alexander came at her so suddenly that she staggered back, letting go of the wall and nearly falling to the pavement. He grabbed her by the arms. “What are you talking about?” he said. “The betrayal—it’s an objective thing. What, you think just because we haven’t told them yet it’s not betrayal?”

“Stop.”

He didn’t. “You think when you can’t look at me because you’re afraid that everybody will see what I see, it’s not betrayal? When your face lights up a block away as you fly out of your stupid job? When you leave your hair down, when those lips of yours quiver? Are they not betraying you?” He was breathing hard.

“Stop it,” she said, red, upset, trying unsuccessfully to wrest herself away from him.

“Tatiana, every single minute that you have spent with me, you have lied to your sister, lied to Dimitri, to your parents, to God, and to yourself. When will you stop?”

“Alexander,” Tatiana said in a whisper, “you stop.”

He let go.

She was panting. “You’re right,” Tatiana said, unable to get a breath out. “But I haven’t lied to myself. That’s why I can’t do this anymore.” She paused. “Please… I don’t want to fight with you. And I don’t have the strength to hurt Dasha. I don’t have the strength for any of this.”

“The strength or the desire, Tania?”

Opening her hands pleadingly, she said, “The strength. I’ve never lied like this in my life.” Realizing what she was admitting, Tatiana flushed with embarrassment, but what could she do? She had to bravely continue. “You have no idea what it costs me every day, every minute, every night to hide from Dasha. My blank stare, my gritted teeth, my casual disregard—do you have any idea what it costs me?”

“Oh, I do,” he said, the grimmest of soldiers. “I’m the one who knows the truth. That’s why I want to end this charade.”

“End it and then what?” Tatiana exclaimed, flaring up. “Have you thought this all the way through?” She raised her voice. “End it and then what? I’ve still got to live with Dasha!” She laughed with exasperation. “What do you think, you think you can call on me after you are through with her? You think after you tell him, after I tell her, you’ll be able to come over, have dinner? Chat with my family? And, Alexander, what about me? Where am I supposed to go? To the barracks with you? Don’t you understand that I sleep in the same bed with her? And that I have nowhere else to go!” Tatiana yelled. “Understand,” she said, “you can do what you like, you can end it with Dasha, but if you do, you will never be able to see me again.”

“Don’t threaten me, Tatiana,” Alexander said loudly, his eyes blazing. “And I thought that was the whole point of this.”

Tatiana groaned, ready to cry.

Lowering his voice, he said, “All right, don’t be upset.” He rubbed her arm.

“Then stop upsetting me!”

He took his hand away.

“Go on with your life,” Tatiana said. “You’re a man.” She lowered her eyes. “Go on with Dasha. She is right for you. She is a woman and I’m—”

“Blind!” Alexander exclaimed.

Tatiana stood on Ulitsa Govorova, desolately failing in the battle of her heart. “Oh, Alexander,” she said, “what do you want from me…”

“Everything!” he whispered fiercely.

Tatiana shook her head, clenching her fists to her chest.

Running his hand down the length of her hair, Alexander said, “Tatia, I’m asking you for the last time.”

“And I’m telling you for the last time,” she said, barely able to get the words out.

Standing tall, Alexander stopped touching her.

She took a step forward, putting her gentle hand on him. “Shura… I don’t own Dasha’s life,” Tatiana said. “I cannot sacrifice my sister’s life. I can’t give it away to please you and me—”

“That’s fine,” he interrupted, pulling his arm away. “You’ve made it very clear. I can see I was wrong about you. You can stop now. But I’m telling you, I’m going to do it my way, not your way. I will end it with Dasha, and you will not see me again.”

“No, please…”

“Will you just go?” Alexander said, pointing down the street. “Walk away from me to the canal. Go home. Go to your Dasha.”

“Shura…” she said with anguish.

“Don’t call me that.” His voice was cold. He folded his arms. “Go, I said! Walk away.”

Tatiana blinked. Every night when they parted, an aching breath left her lungs where Alexander had been. She felt physically emptier in his absence. And up in her room she surrounded herself with other people to feel him less, to want him less. But invariably every night Tatiana had to climb into bed with her sister, and every night Tatiana would turn to the wall begging for strength.

I can do this, she thought. I’ve spent seventeen years with Dasha and only three weeks with Alexander. I can do this. Feel one way. Behave one way, too.

Tatiana turned and walked away.

14

True to his word, the next time Dasha came to see him, Alexander took her for a short walk down Nevsky and told her that he needed some time to himself to think things through. Dasha cried, which he hated, because he hated to see women cry, and she pleaded, which he also did not like much. But he did not relent. Alexander could not tell Dasha he was furious with her younger sister. Furious with a shy, tiny thing who could fit into the palm of his hand if she crouched, yet who would not surrender one stride, not even for him.

A few days later Alexander almost felt glad he wasn’t seeing Tatiana’s face anymore. He found out that the Germans were just eighteen kilometers south of the barely fortified Luga line, which in turn was just eighteen kilometers south of Tolmachevo. Information came into the garrison that the Germans had combed through the entire town of Novgorod in a matter of a few hours. Novgorod, the town southeast of Luga, was where Tatiana cartwheeled into Lake Ilmen.

The People’s Volunteer Army, though tens of thousands strong, had just begun digging the trenches in Luga.

Anticipating the threat of the Finns, most of the resources for field mining, antitank trenching, and concrete reinforcements had gone to the north of Leningrad. The Finnish-Soviet front line in southern Karelia was the best-defended line in the Soviet Union—and the quietest. Dimitri must be happy, Alexander thought. Hitler’s precipitous advance south of Leningrad, however, had caught the Red Army by surprise. They scrambled to build a line of defense along 125 kilometers of the Luga River from Lake Ilmen to Narva. There were some entrenchments, some gun emplacements, some tank traps dug, but not nearly enough. The Leningrad command, realizing that something had to be done and done immediately, loaded the concrete tank barriers from Karelia and trucked them down to Luga.

And all the while the Red Army had been retreating after days of constant fighting.

It wasn’t just retreating. It was relinquishing ground to the Germans at the rate of 500 kilometers in the first three weeks of war. There was no more air support, and the few tanks the Red Army had were insufficient, despite Tatiana’s best efforts. In the middle of July the army comprised mostly rifle squads against the German Panzer units of tanks, mobile artillery, planes, and foot soldiers. The Soviets were running out of arms and out of men.

The hope for defending the Luga line now fell to the hordes of People’s Volunteers, who had no training and, worse, no rifles. They were just a wall of old men and young women standing up against Hitler. What weapons they could pick up, they picked up from the dead Red Army soldiers. Some volunteers had shovels, axes, and picks, but many did not have even that.

Alexander didn’t want to think about how sticks held up to German tanks. He knew.