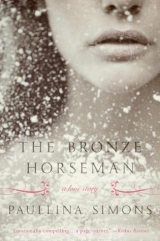

Текст книги "The Bronze Horseman"

Автор книги: Paullina Simons

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 47 страниц)

“Yes, sir,” the three soldiers said in unison. The corporal took his post by the doorway.

Alexander was trying not to smile. “It’s quite a hike up,” he said, his hand on her back, prodding her to the staircase. “Come on.” When they were around a column and not seen by anyone’s eyes, Alexander smiled broadly. “Tania…” he said, “I’m so happy you came to see me.”

Sighing, melting, warming, Tatiana said softly, “Me, too.”

“Did they scare you? They’re harmless,” he said, stroking her hair.

“If they’re so harmless, why did you come down?”

“I heard your voice and theirs. They’re harmless, but you sounded scared.” He was looking at her so…

“What?” Tatiana said shyly.

“Nothing.” Alexander crouched in front of her. “Go on. Grab my neck. Remember how to do this?”

“You’re going to carry me up two hundred stairs?”

“It’s the least I can do after you came all this way. Can you hold my weapon?”

Holding on to the rails, he propelled himself up with her hands around his neck. Hoping he wouldn’t notice, Tatiana silently kissed the back of his military tunic.

Alexander brought her into a glassed-in circular arcade with five columns that partially obstructed the view of the horizon and the sky. Setting her down, he took his rifle from her and propped it against the wall of the gold dome. “We have to go out on the balcony for a clearer view. Will you be all right?” He smiled. “We’re very high up. You’re not afraid of heights, are you?”

“I’m not afraid of heights, no,” Tatiana said, looking up at him.

They walked out onto a narrow outdoor balcony deck circling the arcade above the rotunda. A short iron railing ran around the deck. The view from up here would have been quite striking, Tatiana thought, if only Leningrad weren’t prepared for war. All the lights were extinguished, and in the black of night she could not make out even the white airships floating silently in the dark sky. The air was cool and smelled of fresh water.

“What do you think? Nice up here?” Alexander said, coming up to her. Tatiana couldn’t move if she wanted to. She was between him and the railing.

“Mmm,” she said, peering into the night, afraid to look at him, afraid to let him see her heart. “What do you do here all by yourself, night in and night out?”

“Nothing. Sit on the floor. Smoke. Think.”

Alexander threaded his arms around her waist and closed his hands on her stomach, pressing her into him. She felt his lips at her neck whisper, “Oh, Tatia…”

How instant it was, desire. It was like a bomb exploding, fragmenting and igniting all her nerve endings.

Not desire.

Burning desire for Alexander.

Tatiana tried to move aside, but he held her too tightly. All she wanted was to sink to the ground. Why was that? Why, every time he touched her, did she want to lie down? “Shura, wait,” she said, not recognizing her own voice, which, thick with longing, said, Come here, come, come. Tatiana closed her eyes, muttering, “I don’t see any planes.”

“Me neither.”

“Are they coming?” She moaned softly.

“Yes. The placards are finally right. The enemy is at the gates.” He continued to kiss her under the wisps of her hair.

“Do you think there is any chance we could get out?”

“Not a chance. You’re trapped in the city.” His hot breath and his moist lips on her neck were making her shiver.

“How will it be?”

He didn’t answer.

“You said you wanted to talk to me…” Tatiana said hoarsely.

“Talk?” Alexander said, holding her stomach tight against him.

“Yes, talk… to me… about…” She couldn’t remember what. “Di-mitri?”

He pulled her blouse away and kissed her shoulder blade. “I like your blouse,” he whispered, his mouth on her skin.

“Stop it, Shura, please.”

“No,” he said, rubbing against her back. “I can’t stop.” He breathed into her hair. “Any more than I can stop breathing.”

Alexander’s hands moved to rest below her breasts. Her healing ribs hurt slightly and exquisitely from his touch, and Tatiana couldn’t help herself, she moaned. Squeezing her tighter, he turned her around to him, his mouth on her throat and whispered, “No, you can’t make a sound. Everything carries downstairs. You can’t let them hear you.”

“Then take your hands off me,” Tatiana whispered back. “Or cover my mouth.”

“I’ll cover your mouth, all right,” he said, kissing her fervidly.

After three seconds Tatiana was ready to pass out. “Shura,” she moaned, grasping on to him. “God, you need to stop. How do we stop?” The pulling in her stomach was fierce.

“We don’t.”

“We do.”

“We don’t,” he repeated, his lips on her.

“I don’t mean… I mean, this? How do we ever get relief from this? I can’t go through my days like this, thinking of you. How do we get relief?”

Alexander pulled back from her lips. “The only thing I want in my whole life,” he whispered hotly, “is to show you how we get relief, Tania.” His hands held her to him in a vise.

Tatiana remembered Marina’s words. You are just a conquest to a soldier. And despite herself, despite the unflappable certainty in the things she believed to be true, despite the shining moment with Alexander at the top of the sacred cathedral up in the Leningrad sky, Tatiana’s worst got the better of her. Not trusting her own instincts, scared and doubting, she pushed Alexander away.

“What’s the matter?” he said. “What?”

Tatiana fought for her courage, struggled for the right words, afraid of asking, afraid of hearing his answer, afraid of making him angry or upset. He didn’t deserve it, and in the end she trusted and believed in him so much that it made her like herself less to think that she would give the cynical Marina any credit for her ill-chosen words. Yet the words sat in her chest and churned in her anxious, aching stomach.

Tatiana didn’t want to burden Alexander. She knew he was already carrying plenty. At the same time she could not continue to let him touch her. His hands were tenderly caressing her from her hips up to her hair and back down again. “What’s the matter?” Alexander whispered. “Tania, tell me, what?”

“Wait,” she said. “Shura, can you—” She limped sideways from him. “Wait, just stop, all right?”

He didn’t come after her, and she was a couple of meters away in the arcade when she sank to the floor and gathered her knees to her chest.

“Talk to me about Dimitri,” she said, feeling slightly deflated.

“No,” Alexander said, continuing to stand. He folded his arms. “Not until you tell me what’s bothering you.”

Tatiana shook her head. She just couldn’t have this conversation with him. “I’m fine. Really.” She smiled. Did she manage a good smile? Not according to his long face.

“Just—It’s nothing.”

“All the more reason to tell me.”

Looking down at her long brown skirt, at her toes peeking out from the cast, Tatiana took a few deep breaths. “Shura, this is very, very difficult for me.”

“I know,” he said, crouching where he stood, his arms coming to rest on his knees.

“I don’t know how to say this to you,” she said without lifting her head.

“Open your mouth and speak to me,” said Alexander. “Like always.”

Tatiana couldn’t find her nerve. “Alexander, there are too many more important things for us to resolve, to discuss—” Tatiana managed a quick glance at him. He was studying her with curiosity and concern. “I can’t believe I’m wasting our minutes like this—” She stopped. “But…” He said nothing. “Am I… ?” It was so stupid. What did she know of these things? She sighed. “Listen, you know who helped me get out to see you tonight? My cousin Marina.”

Alexander nodded, unsmiling. “Good. What does she have to do with us? Am I ever going to meet this girl?”

“You might not want to after I tell you what she told me…” Tatiana paused. “About soldiers.” She lifted her eyes. Alexander’s suddenly comprehending and upset face was filled with annoyance, and guilt.

That was not what she wanted to see. “She told me some interesting things.”

“I bet she did.”

“She wasn’t talking about you—”

“That’s a relief.”

“She was trying to warn me about Dimitri, but she said that to soldiers all girls were just a big conquest party and notches in their belt.” Tatiana stopped talking. She thought it was very brave of her to get out even this much.

Slowly Alexander moved over to Tatiana. He didn’t touch her; he just sat by her quietly and finally said, “Do you have a question for me?”

“Do you want a question?”

“No.”

“I won’t ask you then.”

“I didn’t say I wouldn’t answer it. I said I didn’t want it.”

Tatiana wished she could look into Alexander’s face. She just didn’t want to see the guilt there again. And she thought, what if, after our summer, after Kirov, after Luga, after all the unfathomable, breath-dissolving things that I have felt—what if after all that, I will right now find out that Marina was right about Alexander, too? Tatiana could not ask. Yet to have so much of what she felt be built on a lie… How could she not?

“What’s your question?” Alexander repeated, so softly, so patiently, so everything of what he had been to her, that Tatiana, strengthened by him, as always, opened her mouth and in her smallest voice said, “Shura, is that what I am… just another conquest to you? Just more difficult? Am I, too, just another young, difficult notch in your belt?” She lifted her uncertain, vulnerable eyes to him.

Alexander enveloped her in his arms whole, all gathered together like a tiny bandaged package. Kissing her head, he whispered, “I don’t know what I am going to do with you.” Pulling away slightly, he cupped her face. His eyes sparkled. “Tatiasha,” he said beseechingly, “what are you talking about? Have you forgotten the hospital? Conquest? Have you forgotten that if I wanted to, that night, or the following night, or any night that followed, I could have taken it from you standing?” He stared at her and said, even more quietly, “And you would have given it to me standing. Have you forgotten that it was I who put a stop to our senseless desperation?”

Tatiana shut her eyes.

Alexander held her face firmly in his hands. “Come on, open your eyes and look at me. Look at me, Tania.”

She opened her mortified and emotional eyes to find Alexander gazing at her with unremitting tenderness. “Tania, please. You’re not my conquest, you’re not a notch in my belt. I know how difficult it is, what you are feeling. I wish you wouldn’t worry yourself for a second with things you know to be plainly not true.” He kissed her passionately. “Do you feel my lips?” Alexander whispered. “When I kiss you”—he kissed her tenderly—”don’t you feel my lips? What are they telling you? What are my hands telling you?”

Tatiana closed her eyes and moaned. Why did she feel so helpless near him, why? It occurred to her that not only was he right, not only would she have given it to him then, but she would give it to him now, on the cold hard floor of the gilded rotunda. When she opened her eyes, Alexander was looking at her and smiling lightly. “Perhaps,” he said softly, “what you should be asking me is not, are you another notch in my belt, but why aren’t you another notch in my belt?”

Tatiana’s hands were trembling as she held his sleeves. “All right,” she whispered. “Why?”

Alexander laughed.

Tatiana cleared her throat. “Do you know what else Marina told me?”

“Oh, that Marina,” said Alexander, sighing and moving away. “What else did Marina tell you?”

Tatiana curled back into her knees. “Marina told me,” she said, “that all soldiers have it off with garrison hacks nonstop and never say no.”

“My, my,” said Alexander, shaking his head. “That Marina is trouble. It’s a good thing you didn’t get off the bus to go and see her that Sunday in June.”

“I agree,” said Tatiana, her face melting at the memory of them on that bus.

And his face melted back.

What was she even thinking? What was she even doing? Tatiana shook her head, upset at herself.

“Now, listen to me. I didn’t want to tell you any of this, but…” Alexander drew a deep breath. “When I first got into the army, I saw that genuine relationships with women were going to be very difficult because of the nature of our confinement”—he shrugged—”and the realities of Soviet life. No rooms, no apartments, no hotels for the Soviet man and the Soviet woman to go to. You want the truth from me? Here it is. I don’t want you to be afraid of it or afraid of me because of it. On our weekend furlough, it is true, we would go out for some beers and often find ourselves in the presence of all kinds of young women, who were quite willing to… knock around with soldiers without any strings attached.” Alexander stopped.

“And did you”—Tatiana held her breath—”knock around?”

“Once or twice,” Alexander replied. He didn’t look at her. “Don’t be upset by this, please.”

“I’m not upset,” Tatiana mouthed. Stunned, yes. Torn with self-doubt, yes. Entranced by you, yes again.

“We were all just having a bit of youthful fun. I kept myself extremely unattached and detached. I hated entanglements—”

“What about Dasha?”

“What about her?” Alexander said tiredly.

“Was Dasha… ?” Tatiana couldn’t get the words out.

“Tatia, please,” said Alexander, shaking his head. “Don’t think about these things. Ask Dasha what kind of a girl she was. I’m not the one to tell you.”

“Alexander, but Dasha is an entanglement!” Tatiana exclaimed. “Dasha does have strings attached to her. Dasha has her heart.”

“No,” he said. “She has you.”

Tatiana sighed heavily. This was too hard for her—talking about Alexander and her sister. Hearing about Alexander and meaningless girls was easier than hearing about one Dasha. Tatiana sat with her hands around her knees. She wanted to ask him about the present time but couldn’t get the words out. She didn’t want to ask him about anything. She wanted to go back to how it was before the night in the hospital, before the wretched confusion of her body blinded her to the truth she felt about him.

Alexander rubbed her thighs. “I can feel you’re afraid.” Quietly, he added, “Tania, I beg you—don’t let stupidity come between us.”

“All right,” she said with remorse.

“Don’t let bullshit that has nothing to do with us keep you away from me. We already have so much keeping you away from me.” He paused. “Everything.”

“All right, Alexander.”

“Let it all fall away, Tatiana. What are you afraid of?”

“I’m afraid of being wrong about you,” she whispered.

“Tania, how could you of all people be wrong about me?” Alexander clenched his fists in frustration. “Can’t you see,” he said, “it’s exactly because of who I had been that I came to you? What’s the matter?” he asked. “You couldn’t see my loneliness?”

“Barely,” Tatiana replied, clutching her hands to her chest, “through my own.” Falling back against the railing, Tatiana said, “Shura, I’m surrounded by half-truth and innuendo. You and I don’t have a moment to talk anymore, like we used to, a moment to be alone—”

“A moment of privacy,” said Alexander, speaking the last word in English.

“Of what?” She didn’t know that word. She would have to look it up when she got home. “What about now? Besides Dasha, are you still—”

“Tatiana,” said Alexander, “all the things you’re worried about—they’re gone from my life. Do you know why? Because when I met you, I knew that if I continued and a good girl like you ever asked me about them, I wouldn’t be able to look you in the face and tell you the truth. I would have to look you in the face and lie.” He was looking into her face. The wordless truth was in his eyes.

Tatiana smiled at him and breathed out, the tight, sick feeling in her stomach dissolving with her exhaled breath. She wanted him to come and hug her. “I’m sorry, Alexander,” she whispered. “I’m sorry for my doubt. I’m just too young.”

“You’re too much of everything,” he said. “God!” he exclaimed. “How insane this is—never to have the time to explain, to talk anything out, never to have a minute—”

We’ve had a minute, Tatiana thought. We had our minutes on the bus. And at Kirov. We had our minutes in Luga. And in the Summer Garden. Breathless minutes, we had. What we want, she thought, keeping herself from welling up, is eternity.

“I’m sorry, Shura,” Tatiana said, grasping his hands. “I didn’t mean to upset you.”

“Tania, if only we could have a moment of privacy,” Alexander said, again speaking the last word in English, “you would never doubt me again.”

“What is this privacy?” she repeated.

Alexander smiled sadly. “Being secluded from the view or from the presence of other human beings. When we need to be alone together to have intimacy, that’s impossible in two rooms with six other people,” he explained in Russian. “We say, we want some privacy.”

“Oh.” Tatiana blushed. So that was the word she had been searching for, ever since she met him! “There is no word for anything like that in Russian.”

“I know,” he said.

“And there is a word for this in America?”

“Yes,” said Alexander. “Privacy.”

Tatiana remained silent.

Alexander slid closer, putting both his legs around her. “Tania, when will we next have a moment alone?” he asked, peering into her eyes.

“We’re alone now,” she said.

“When will I next be able to kiss you?”

“Kiss me now,” she whispered.

But Alexander didn’t. He said grimly, “Do you know that it might be never? The Germans are here. Do you know what that means? Life, as you knew it, is over.”

“What about this summer?” she asked. “Nothing’s been quite the same since June 22.”

“No, it hasn’t,” he agreed. “But before today we were simply arming ourselves. Now it’s war. Leningrad will be the battleground for your freedom. And at the end, how many of us will be left standing? How many of us will be free?”

Oh, God. “Is that why you come every chance you get, even if it means dragging Dimitri with you?” Tatiana asked.

With a small nod and a large sigh, Alexander said, “I’m always afraid it’ll be the last time I’m going to see your face.”

Tatiana swallowed, curled into her knees. “Why… do you always drag him with you?” she asked. “Can’t you ask him to leave me alone? He doesn’t listen to me. What am I going to do with him?”

Alexander made no reply, and Tatiana anxiously tried to catch his eye. “Tell me about Dimitri, Shura,” she said quietly. “What do you owe him?”

Alexander looked at his cigarettes.

Faintly Tatiana said, “Do you owe him… me?”

“Tatiana,” Alexander said, “Dimitri knows who I am.”

“Stop,” she uttered almost inaudibly.

“If I tell you, you won’t believe it,” Alexander said. “Once I tell you, there will be no going back for us.”

“There is no going back for us now,” Tatiana said, and wanted to mouth a prayer.

“I don’t know what to do about him,” Alexander said.

“I will help you,” said Tatiana, her heart scared and swelling. “Tell me.”

Alexander moved away on the narrow balcony to sit diagonally across from her against the wall, stretching his legs out to her. Tatiana continued to sit against the railing. She sensed he didn’t want her too close. Taking off her one shoe, Tatiana stretched her bare feet out to his boots. Her foot was half the size of his.

Shuddering as if trying to stave off a beast, Alexander began. “When my mother was arrested,” he said, not looking at Tatiana, “the NKVD came for me, too. I wasn’t even able to say good-bye to her.” Alexander looked away. “I don’t like to talk about my mother, as you can imagine. I was accused of distributing some capitalist propaganda when I had been fourteen, still in Moscow, and going to Communist Party meetings with my father. So at seventeen, in Leningrad, I was arrested and taken right to Kresty, the inner-city prison for nonpolitical criminals. They didn’t have room for me at Shpalerka, the Big House, the political detention center. I was convicted in camera in about three hours,” Alexander said with scorn. “They didn’t even bother with an interrogation. I think all their interrogators were tied up with more important prisoners. I got ten years in Vladivostok. Can you imagine?”

“No,” said Tatiana.

“You know how many of us finally got on that train headed for Vladivostok? A thousand. One man said to me, ‘Oh, I just got out, and now this again.’ He told me the prison camp we were going to had 80,000 people in it. Eighty thousand, Tania! One camp. I told him I didn’t believe it. I had just turned seventeen.” Alexander looked at her. “Like you are now.” He continued, “What could I do? I couldn’t spend ten years of my youth in prison, could I?”

“No,” she said.

“I had always believed, you see, that I was meant to live a good life. My mother and father believed in me. I believed in myself—” He broke off. “Prison never entered into it. I never stole, I never broke windows, I didn’t terrorize old ladies. I did nothing wrong. I wasn’t going. So,” he said, “we were crossing the river Volga, near Kazan, thirty meters up over a precipice. I knew it was either now or I was going to Vladivostok for what seemed to me like the rest of my life. I had too much hope for myself. So I jumped right into the river.” Alexander laughed. “They didn’t even stop the train. They thought for sure I had died in the fall.”

“They didn’t know who they were dealing with,” said Tatiana, wanting to put her arms around him, but he was too far away. “When you jumped, was that when you found out you indeed could swim?” She smiled.

Alexander smiled back. The soles of his boots were touching the soles of her feet. “I could swim a little bit.”

“Did you have anything on you?”

“Nothing.”

“Papers? Money?”

“Nothing.” Tatiana thought Alexander wanted to tell her something else, but he continued. “It was the summer of 1936. After I escaped, I made my way south on the Volga, on fishing boats, by foot, in the back of horse carriages. I fished, worked briefly on farms, and moved on south. From Kazan to Ulyanovsk, where Lenin was born—interesting city, like a shrine. Then to Saratov, downstream on the Volga, fishing, harvesting, moving on. Wound up in Krasnodar, near the Black Sea. I was headed down south into Georgia, and then Turkey. I hoped to cross the border somewhere in the Caucasus Mountains.”

“But you had no money.”

“None,” Alexander said. “But I made some along the way, and I did think that my English, once I got into Turkey, would help me. But in Krasnodar, fate intervened.” He glanced at her. “As always. It was a brutal winter, and the family I was staying with, the Belovs—”

“The Belovs?” exclaimed Tatiana.

Alexander nodded. “A nice farming family. Father, mother, four sons, one daughter.” He cleared his throat. “Me. We all got typhus. The entire village of Belyi Yar—360 people—got typhus. Eight-tenths of the village population perished, including the Belovs, the daughter first. The local council from Krasnodar, with the help of the police, came and burned down the village, for fear that the epidemic would spread to the nearby city. All my clothes were burned, and I was quarantined until I either died or got better. I got better. The local Soviet councilman came to issue me new papers. Without a moment’s hesitation I said I was Alexander Belov. Since they burned the village in its entire—” Alexander raised his eyebrows. “Only in the Soviet Union. Anyway, since they burned the village, the councilman could not confirm or deny my claim to be Alexander Belov, the youngest Belov boy.”

Tatiana closed her mouth.

“So I was issued a brand-new domestic passport and a brand-new identity. I was Alexander Nikolaevich Belov, born in Krasnodar, orphaned at seventeen.” He looked away.

“What was your full American name?” asked Tatiana faintly.

“Anthony Alexander Barrington.”

“Anthony!” she exclaimed.

Alexander shook his head. “Anthony was for my mother’s father. I myself was never anything but Alexander.” He pulled out a cigarette. “You don’t mind?”

Tatiana shook her head.

“Anyway,” he said, “I returned to Leningrad and went to stay with relatives of the Belovs. I needed to be back in Leningrad—” Alexander hesitated. “I’ll tell you why in a minute. I stayed with my ‘aunt,’ Mira Belov, and her family. They lived on the Vyborg side. They hadn’t seen their nephews in a decade; it was ideal. I was like a stranger to them.” He smiled. “But they let me stay. I finished school. And it was in this school that I met Dimitri.”

“Oh, Alexander,” said Tatiana. “I cannot believe what you lived through when you were so young.”

“I’m far from finished. Dimitri was one of the kids I played with at school. He was spindly, unpopular, and never much fun. When we played war at recess, he was always the one taken prisoner. Dimitri POW Chernenko we used to call him. We said that for him alone the Soviet Union should have signed the 1929 Geneva Convention, because he was getting himself wounded or taken prisoner or killed every time we played, managing to get himself caught somehow without help from anyone.”

“Please go on.”

“But then I found out that his father was a prison guard at Shpalerka.” Alexander stopped.

Tatiana stopped breathing. “Your parents were still alive?”

“I didn’t know,” Alexander said. “So I chose to become close to Dimitri. I hoped that maybe he could help me see my mother and father. I knew that if they were alive, they would be tortured by their worries about me. I wanted to let them know I was all right.” He paused. “My mother particularly,” he said, his voice controlled. “We had been very close once.”

Tatiana’s eyes filled with tears. “What about your father?”

With a shrug, Alexander said, “He was my father. We had some conflict in the last years. What can I say? He thought he knew everything. I thought I knew everything. So it went.”

Tatiana did not blink as she stared at Alexander, transfixed. “Shura, they must have loved you so much.” She swallowed hard.

“Yes,” Alexander said, taking a deep, pained drag of the cigarette. “They did once love me.”

Tatiana’s heart was breaking for Alexander.

“Little by little,” he continued, “I gained Dimitri’s confidence, and we became better and better friends. Dima really liked the fact that I picked him out of many to be my closest friend.”

“Oh, Shura,” said Tatiana. She understood. Crawling to him, Tatiana wrapped her arms around Alexander. “You had to trust Dimitri.”

With one arm he hugged her back. The other held his cigarette. “Yes. I had to tell him who I was. I had no choice but to trust him. Leave my parents to die, or trust him.”

“You trusted Dimitri,” Tatiana repeated incredulously, letting go of him and sitting close by his side.

“Yes.” Alexander looked down into his large hands, as if trying to find the answer to his life in them. “I didn’t want to trust him. My father, the good Communist that he was, taught me never to trust anyone, and though it wasn’t easy, I learned that lesson well. But it’s a hard way to live, and I wanted to trust just one person in my life. Just one. I really needed Dimitri’s help. Besides, I was his friend. I said to myself that if he did this for me and I got to see my mother and father, I would be his friend for life. And that’s exactly what I told him. ‘Dima,’ I said, ‘I will be your friend for life. I will help you in any way that I can.’ “ Alexander lit another cigarette. Tatiana waited, the aching in her chest increasing.

“Dimitri’s father found out that I was too late to see my mother.” Alexander’s voice cracked. “He told me what had happened to her. But my father was still alive, though apparently not for long. He’d already been in prison for nearly a year. Chernenko got Dimitri and me inside Shpalerka, and then we had five minutes with the foreign infiltrator, Harold Barrington. Me, my father, Dimitri, his father, and another guard. No privacy for me and my father.”

Tatiana took Alexander’s hand. “How was that?”

Alexander stared straight ahead. “Pretty much how you imagine it might be,” he said, keeping his voice even. “And bitterly brief.”

In the small gray concrete cell, Alexander looked at his father, and Harold Barrington looked at Alexander. Harold did not move from his bed.

Dimitri stood in the center of the small cell, Alexander to the side. The guard and Dimitri’s father were behind them. A single lightbulb hung from the ceiling.

In Russian, Dimitri said to Harold, “We are here for only a minute, comrade. You understand? Just for a minute.”

“All right,” replied Harold in Russian, blinking back tears. “Thank you for coming to see me. I’m happy to see two Soviet boys. Your name, son?” he asked Dimitri.

“Dimitri Chernenko.”

“And your name, son?” His body shaking, Harold looked at Alexander.

“Alexander Belov,” said Alexander.

Harold nodded.

The guard said, “All right, enough gawking at the prisoner. Let’s go.”

Dimitri said, “Wait! We just wanted the comrade to know that despite his crime against our proletarian society, he will not be forgotten.”

Alexander said nothing, his eyes on his father.

“It’s because of his crime against our society that he will not be forgotten,” said the guard.

Chewing his lips, Harold looked at Dimitri and Alexander, whose back was to the guard but whose face was to his father.

“Popov, can I shake their hands?” Harold asked the guard.

The guard shrugged, stepping forward. “I’m going to watch you do it. Make it quick.”

Alexander said, “I’ve never heard English before, Comrade Barrington. Can you say something for us in English?”

Harold came up to Dimitri and shook his hand. “Thank you,” he said in English.

Then he came up to Alexander and took his hand, holding it tightly between his. Alexander shook his head slightly, trying to will his father to stay calm.

In English, Harold whispered, “Would that I had died for thee, O Absalom, my son, my son!”

Alexander mouthed, Stop.

Letting go of Alexander’s hand, Harold stepped slightly away, struggling not to cry and failing. “I’ll tell you something in English,” he said in Russian. “A few corrupted lines from Kipling.”

“Enough,” said the guard. “I have no time—”

“If you can bear to hear the truth you’ve spoken,” Harold said loudly in En-glish, “twisted by knaves to make a trap for fools…” Tears rolled down his face. “Or watch the things you gave your life to, broken…” He was down to a whisper. “Son!—stoop and build them up with worn-out tools.” Harold stepped back and made a small sign of the cross on Alexander.

“Let’s go!” yelled the guard.