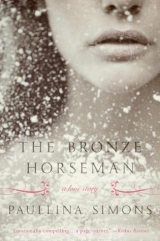

Текст книги "The Bronze Horseman"

Автор книги: Paullina Simons

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 47 страниц)

Smoke and Thunder

TATIANA’S world changed after Alexander stopped coming to see her. She was now one of the last people to leave work. As she slowly walked out the double doors of the factory, she still turned her head expectantly, hoping that maybe she would see his head, his uniform, his rifle, his cap in his hands.

Down the length of the Kirov wall Tatiana walked, waiting for the buses to pick up passengers. She sat on the bench and waited for him. And then she walked the eight kilometers back to Fifth Soviet, looking for him, seeing him, in fact, everywhere. By the time she would get home at eleven or later, the dinner her family had prepared at seven was old and cold. At home everyone listened tensely to the radio, not speaking about the only thing that was on their minds—Pasha.

Dasha came home one evening in tears and told Tatiana that Alexander wanted to take a break. She cried for five straight minutes while Tatiana gent-ly patted her back. “Well, I’m not going to give up, Tania,” said Dasha. “I’m not. He means too much to me. He is going through something. I think he is afraid of commitment, like most soldiers. But I’m not going to give up. He said he needed a little time to think. That doesn’t mean forever; that’s just until he sorts himself out, right?”

“I don’t know, Dashenka.” What kind of person said he was going to do something and then did? No person Tatiana knew.

Dimitri came to see her once, and they spent an hour together surrounded by her family. She was mildly surprised that he hadn’t been by more often, but he made some—Tatiana thought lame—excuse. He seemed distracted. He had no information on the position of the Germans in the Soviet Union. His mouth on her cheek at the end of the night was as distant as Finland.

Up on the roof the kids from the building looked for excitement, for incendiary bombs to put out. There weren’t any bombs. It was quiet at night, except for the laughing of Anton and his friends next to her, except for the beating of her heart.

Up on the roof Tatiana thought about the evening minute, the minute she used to walk out the factory doors, turn her head to the left even before her body turned, and look for his face. The evening minute as she hurried down the street, her happiness curling her mouth upward to the white sky, the red wings speeding her to him, to look up at him and smile.

At night she was still turned to the wall, her back to the absent Dasha, who was never home.

Tatiana would have continued this wretched way, but one morning the Metanovs heard on the radio that the Germans were trouncing their way through the countryside and, despite all measures taken by the heroic Soviet soldiers, were nearly at Luga. It wasn’t the Luga part that stunned the family and made them unable to eat or talk to each other. It was that they all knew that Luga was mere kilometers from Tolmachevo, where Pasha was safely, they thought—no, were sure—ensconced at camp.

If the Germans were about to steamroll through Luga, what was to happen to Tolmachevo? Where was their son, their grandson, their brother?

Tatiana tried to console her family with hollow words. “He is fine, he’ll be all right.” When that didn’t work, she tried, “We’ll get in touch with him. Come on, Mama, don’t cry.” When that didn’t work, she tried, “Mama, I can feel him still out there. He is my twin brother. He is all right, I’m telling you.” Nothing worked.

There remained no word on Pasha, and Tatiana, despite her brave talk, became increasingly afraid for her brother.

The local Soviet had no answers. The borough Soviet also had no answers. Tatiana and her mother went there together.

“What can I tell you?” the stern, mustachioed woman told Mama. “My information says only that the Germans are near Luga. It doesn’t say anything about Tolmachevo.”

“Then why isn’t there any answer when we try to call the camps?” Mama demanded. “Why are the phones not working?”

“Who do I look like, Comrade Stalin? Do I have all the answers?”

“Can we get to Tolmachevo?” Mama asked.

“What are you talking about? Can you get to the front? Can you take a bus, comrade, to the front? Yes, sure. Good luck to you.” The woman’s gray mustache moved as she laughed. “Natalia, come here, you have to hear this.”

Tatiana wanted to say something rude back, but she couldn’t muster the courage. Wishing she had tried harder to convince her family about Pasha, she led her mother out of the borough council office.

That night when Tatiana was pretending to sleep, her face to the wall, her hand on the floor below on Alexander’s copy of The Bronze Horseman, she overheard her parents whispering tearfully to each other. It started with her mother’s quiet sobbing, followed by her father’s comforting “Shh, shh.” Then he was sobbing, too, and Tatiana wanted to be anywhere but where she was.

Little whispers came to her, fragmented sentences, mournful longings.

“Maybe he is all right,” she heard her mother say.

“Maybe,” echoed her father.

“Oh, Georg. We can’t lose our Pasha. We can’t.” She moaned. “Our boy.”

“Our favorite boy,” added Papa. “Our only son.”

Mama sobbed.

Tatiana heard the sheets rustling. Her mother sniffed.

“What kind of God would take him away?”

“There is no God. Come now, Irina,” Papa said in a comforting voice. “Not so loud. You’ll wake the girls.”

Mama cried out. “I don’t care,” she said, nonetheless lowering her voice to a whisper once more. “Why couldn’t God take one of them?”

“Irina, don’t say that. You don’t mean it.”

“Why, Georg, why? I know you feel the same way. Wouldn’t you give up Tania for our son? Or even Dasha? But Tania is so timid and weak, she’s never going to amount to anything.”

“What kind of a life can she have here anyway, timid or not?” said Tatiana’s father.

“Not like our son,” said Mama. “Not like our Pasha.”

Tatiana put the sheet over her ears so she wouldn’t hear any more. Dasha continued to sleep. Mama and Papa soon fell asleep themselves. But Tatiana remained awake, the words crashing their agonizing tune on her ears. Why couldn’t God take Tania instead of Pasha?

2

The next day after work, filled with apprehension, not believing her own nerve, Tatiana went to Pavlov Barracks. To a smiling Sergeant Petrenko she gave Alexander’s name and waited, standing against the wall, hoping for some strength in her legs.

Minutes later Alexander walked through the gate. The sharply tense expression on his face dissolved momentarily into… but only momentarily. He had circles under his eyes. “Hello, Tatiana,” he said coolly, and stood a polite distance from her in the dank passageway. “Is everything all right?”

“Sort of,” Tatiana replied. “What about you? You look—”

Blinking, Alexander replied, “Everything is fine. How have you been?”

“Not so good,” Tatiana admitted and became immediately afraid he would think it was because of him. “One thing…” She wanted to keep her voice from breaking. There was fear for Pasha, but there was something else, too. She didn’t want Alexander to know it. She would try to hide it from him.

“Alexander, is there a way you could find out for us about Pasha… ?”

He looked at her with pity. “Oh, Tania,” he said. “What for?”

“Please. Could you?” She added, “My parents, they’re in despair.”

“Better not to know.”

“Please. Mama and Papa need to know. They just can’t function.” I need to know. I just can’t function.

“You think it would be easier if they knew?”

“Absolutely. It’s always better to know. Because then they could deal with the truth.” She looked away even as she was speaking. “This is breaking them apart, the uncertainty over him.” When Alexander didn’t reply, Tatiana, chewing her lip, said, “If they knew, then Dasha and I and maybe Mama, too, would go to Molotov with Deda and Babushka.”

Alexander lit a cigarette.

“Will you try—Alexander?” She was glad to say his name out loud. She wanted to touch his arm. So happy and so miserable to see his face again, she wanted to come closer to him. He wasn’t wearing his full uniform. He must have come from his quarters, because he wore a barely buttoned shirt that was not even tucked into his army trousers. Couldn’t she come closer to him? No, she couldn’t.

He smoked silently. Tilting his head, he didn’t stop looking at her. Tatiana tried not to show him the expression in her eyes. She mustered a pale smile.

“You will go to Molotov?” Alexander asked.

“Yes.”

“Good,” Alexander said without inflection or hesitation. “Tania, whether or not I will find out about Pasha, know this—you have to go. Your grand-father is lucky to get a post. Most people are not getting evacuated.”

“My parents say the city is still the safest place right now. That’s why so many thousands are coming to Leningrad from the countryside,” Tatiana said with quiet authority.

“No place in the Soviet Union is safe,” said Alexander.

“Careful,” she said, lowering her voice.

Alexander leaned toward her, and Tatiana raised her eyes to him, not just eagerly but avidly. “What? What?” she whispered, but before he could say anything, Dimitri sprinted out of the gate.

“Hi!” he said to Tatiana, frowning. “What are you doing here?”

“I was coming up to see you,” said Tatiana quickly.

“And I’m having a smoke,” said Alexander.

“He needs to stop smoking just as you’re coming up to see me,” Dimitri said to Tatiana. He smiled. “Very nice of you to come, though. I’m touched.” He put his arm around her. “Let me walk you home, Tanechka,” he said, leading her away. “Do you want to go somewhere? It’s a nice evening.”

“See you, Tania,” she heard Alexander call after her. Tatiana was ready to break down.

Alexander went to see Colonel Mikhail Stepanov.

Alexander had served under Colonel Stepanov in the Winter War of 1940 with Finland, when the colonel was a captain and Alexander was a second lieutenant. The colonel had had many chances for promotion, not just to brigadier but to major general, but he refused, preferring to keep his rank and run the Leningrad garrison.

Colonel Stepanov was a tall man, nearly as tall as Alexander. He was slender and carried himself stiffly, but the movements of his body were gentle, and in his blue eyes hung a sad haze that remained even when he smiled at Alexander.

“Good morning, sir,” Alexander said, saluting him.

“Good morning, Lieutenant,” said the colonel, coming out from behind his desk. “At ease, soldier.” They shook hands. Then Stepanov stepped away and went back behind his desk. “How are you?”

“Very well, sir.”

“What’s going on? How is Major Orlov treating you?”

“Everything is fine, sir. Thank you.”

“What can I do for you?”

Alexander cleared his throat. “I just came for some information.”

“I said at ease.”

Alexander moved his feet apart and placed his hands behind his back. “The volunteers, sir, what’s been happening to them?”

“The volunteers? You know what’s been happening, Lieutenant Belov. You’ve been training them.”

“I mean near Luga, near Novgorod.”

“Novgorod?” Stepanov shook his head. “The volunteers were involved in some battles there. The situation in Novgorod is not good.”

“Oh?”

“Untrained Soviet women throwing grenades at Panzer tanks. Some didn’t even have grenades. They threw rocks.” Colonel Stepanov peered into Alexander’s face. “What’s your interest in this?”

“Colonel,” said Alexander, clicking his heels together, “I’m trying to find a seventeen-year-old boy who went to a boys’ camp near Tolmachevo. There is no answer from the camps, and his family is panicked.” Alexander paused, staring at the colonel. “A young boy, sir. His name is Pavel Metanov. He went to a camp in Dohotino.”

The colonel stood quietly for a few moments, studying Alexander, and finally said, “Go attend to your duties. I’ll see what I can find out. I’m not promising anything.”

Alexander saluted him. “Thank you, sir.”

Later that evening Dimitri came to the quarters Alexander shared with three other officers. They were all playing cards. A cigarette hung languidly in Alexander’s mouth as he was shuffling. He barely turned his head to look at Dimitri.

Crouching beside Alexander’s chair, Dimitri cleared his throat.

“Salute your commanding officer, Chernenko,” said Second Lieutenant Anatoly Marazov, not looking up from his cards. Dimitri stood and saluted Marazov. “Sir,” he said.

“At ease, Private.”

“What’s going on, Dima?” Alexander asked.

“Not much,” said Dimitri quietly, crouching again. “Nowhere to go and talk?”

“Talk right here. Everything all right?”

“Fine, fine. Rumors are we’re staying put.”

“We’re not staying put, Chernenko,” said Marazov. “We’re staying to defend Leningrad.”

“The Finns are calling themselves co-belligerents.” Dimitri snorted derisively. “If they ally with the Germans, we’re as good as dead. We might as well hang up our arms.”

“That’s the spirit,” said Marazov. “Belov, did you give me this soldier?”

Alexander turned to Dimitri. “Lieutenant Marazov is right. Dima, I’m surprised by your attitude. Frankly, it’s not like you.” Alexander stopped his voice from inflection.

Dimitri smiled slyly. “Alexander,” he said, “not quite what we hoped for when we joined the army?”

When Alexander didn’t reply, Dimitri said, “I mean, war.”

“No, war was not what I hoped for. Is it what anyone hopes for?” Alexander paused. “Is it what you hoped for?”

“Not at all, as you know. But I had far fewer choices than you.”

“You had choices, Belov?” asked Marazov.

Putting down his cards, Alexander stubbed out his cigarette and stood up. “I’ll be right back,” he said to the other officers and strode out. With smaller footsteps Dimitri followed behind. There were too many officers in the corridor; they walked downstairs and through the side door, out onto the cobbled courtyard. It was past one in the morning. The sky was three shades darker than gray.

A few feet away from them three soldiers stood smoking. But this was as alone as they were going to get. Alexander said, “Dima, you need to stop this nonsense. I had no choices. Don’t go believing that. What choices did I have?”

“The choice to be somewhere else.”

Alexander made no reply. He wished he were anywhere else, other than standing in front of Dimitri, who said, “Finland is too dangerous for us right now.”

“I know.” Alexander did not want to talk about Finland.

“Too many men on both sides, NKVD border troops everywhere. The Lisiy Nos area is full of troops—theirs and ours—and barbed wire and mines. It’s not safe at all. I don’t know what we’re going to do. Are you sure the Finns will come down to Lisiy Nos from Vyborg?”

Alexander smoked and said nothing. Finally he spoke. “Yes. Eventually. They will want their old borders back. They’ll come to Lisiy Nos.”

“What else can we do? We’ll bide our time then,” Dimitri said. When Alexander didn’t comment, Dimitri continued. “Will the right time ever come again, Alex?”

“I don’t know, Dima. We’ll have to wait and see.”

Dimitri sighed. “Well, in the meantime, can you move me out of the First Rifle Regiment?”

“Dima, I already got you out of the Second Infantry Battalion.”

“I know, but I’m still too close to possible attack. Marazov’s men are the second line. I’d rather be recon, or clean-up. Or running supplies, something like that.” He paused. “Best chance for success in running, don’t you think?”

“You want to be running supplies? Ammunition to front-line troops?” Alexander asked with surprise.

“I was thinking more of mail and cigarettes to rear units.”

Alexander smiled. “I’ll see what I can do, all right?”

“Come on,” Dimitri said, stubbing out his cigarette on the pavement. “Try to be more cheerful. What’s the matter with you these days? Everything is all right still. The Germans aren’t here; we’re having a great summer.”

Alexander said nothing.

“Alex,” said Dimitri, “I wanted to talk to you about something… . Tania is such a nice girl.”

“What?”

“Tania. She is such a nice girl.”

“Yes.”

Dimitri said nothing for a while. “And I want her to stay that way. She really shouldn’t be coming here. And talking to you, of all people.”

“I agree.”

“I know we’re all good friends, and she is the kid sister of your fancy-woman, but frankly, I don’t want your reputation rubbing off on my nice girl. After all,” Dimitri said, “she is not like one of your garrison hacks—”

Taking a step toward Dimitri, Alexander said, “That’s enough.”

Dimitri laughed. “I’m just joking. Is Dasha still coming to see you? I haven’t been over there much. Tania works crazy hours. Dasha still comes, though, right?”

“Yes.” Every night without fail Dasha would show up, trying everything she knew to get him back. But he wasn’t about to tell Dimitri his business with Dasha.

“Well, all the more reason Tania shouldn’t come here. It would upset Dasha needlessly, wouldn’t it, if she were to find out?”

“I’m sure you’re right.” Alexander stared at Dimitri, who did not blanch. “Have you got another cigarette?”

Dimitri immediately reached into the pocket of his khaki trousers. “Love it. A first lieutenant asking a lowly private for a fag. I always like it when you ask me to do something for you.”

Alexander took the cigarette and said nothing.

Dimitri cleared his throat. “If I didn’t know any better, I’d say you had some feelings for the diminutive Tanechka.”

“But you know better, don’t you?”

Dimitri shrugged. “I guess. Just the way you were looking at her—”

“Forget it,” said Alexander, cutting him off and taking a deep drag of the cigarette. “It’s in your head.”

Dimitri gave a sigh. “I know, I know,” he said. “What can I say? I’ve fallen bad for that girl.”

The cigarette slowly burned to ash between Alexander’s fingers. “You have?” he asked at last.

“Yes. Why is that such a surprise?” Dimitri laughed wholeheartedly. “You think a cad like me is too low for a girl like Tania?”

“No, not at all,” Alexander said. “But from what I’ve heard, you haven’t stopped your Sadko activities.”

Dimitri shrugged. “What does that have to do with anything?” Before Alexander could reply, Dimitri came a little closer to him, lowered his voice, and said, “Tania is young and has asked me to go slow. I am very respectful of her wishes and patient with her.” He arched his eyebrows. “She is really coming around, though—”

Alexander threw down the cigarette butt and stamped it out with his boot. “All right, then,” he said. “We’re finished here.” He started walking back to his building.

Dimitri caught up with him and grabbed him by the arm.

Alexander whirled around, yanking his arm easily from Dimitri’s grip. “Don’t grab me, Dimitri.” His eyes flashed. The sky turned another shade of gray. “I’m not Tatiana.”

Taking a few quick steps back from Alexander, Dimitri said, “All right, all right. Stop it.” He took another step back. “You’ve really got to do something about that temper of yours, Alexander Barrington.” He enunciated every syllable. And then he backed farther away and smiled. He seemed smaller, his little teeth sharper and more yellow, his hair more greasy, his eyes narrower in the coming of night.

3

Tatiana ran to work the next morning, carrying hope with her. She had learned to ignore the ignoble, ever-present, blue-uniformed NKVD militia troops standing by the front doors of Kirov with their obscene rifles, walking through the factory floors, almost marching, carrying their weapons close to their hips. A few of them would look at her as she passed by, and it was the only time in her life when she wished she were smaller than she already was and less noticeable. With their grave, unyielding faces, they stared at Tatiana, hardly blinking, while she blinked frequently as she hurried past them, pushing through the doors, to the relative anonymity of the assembly line.

So that the workers didn’t get bored and therefore negligent on any one production facet of the KV-1, they were moved around every two hours. Tatiana went from working the pulley that lifted the treadless tank and placed it on tread, to painting the red star on a finished tank ready to be flatbedded and put into production. She spray-painted not only the red star but the white words for stalin! on the hull that stood out markedly against the glossy green paint.

Ilya, the skinny boy with the crew cut, had not left Tatiana alone after Alexander stopped coming at night. He would ask her all sorts of questions that she was too polite not to answer, but in the end even Tatiana gave way to slight rudeness. I have to concentrate on my work, she would tell him, wondering how in the world he always managed to get a position next to her, no matter how many times she got transferred during the day to different tank-building responsibilities. In the canteen Ilya would get his plate and sit next to her and Zina, who could not stand him and frequently told him so.

But today Tatiana felt sorrier for him. “He is just lonely,” she said, biting into her meat cutlet, lapping up the gravy, her mouth full. “He doesn’t seem to have anybody. Stay, Ilya.” So Ilya stayed.

Tatiana could afford to be generous. She couldn’t wait for her day to end. After going to see Alexander yesterday, she was certain he would come after work to see her at Kirov. She wore her lightest skirt and her lightest, softest blouse, and even had a bath in the morning, having just taken one the night before.

That evening she ran out of the Kirov doors, her golden hair shining and down, her face scrubbed and pink, and turned her smiling head, breathless for Alexander.

He wasn’t there.

It was after eight, and she sat on the bench until after nine with her hands on her lap. Then she got up and walked home.

There was no news of Pasha, and Mama and Papa were miserable. They kept crying intermittently. Dasha was not home. Deda and Babushka were slowly packing their things. Tatiana went out onto the roof and sat watching the airships float like white whales across the northern sky, listening to Anton and Kirill reading Tolstoy’s War and Peace, evoking their brother Volodya, lost in Tolmachevo. Tatiana listened with half an ear, thinking of her brother Pasha, lost in Tolmachevo.

Alexander didn’t come to see her. He had no news. Or the news he had was bad and he couldn’t face her. But Tatiana knew the truth: he didn’t come to see her because he was done. Done with her, with her childish ways, done with that part of his life. They had been friends walking in the Summer Garden, but he was a man, and now he was done.

He was right, of course, not to come. And she would not cry.

But to face Kirov day after day without him and without Pasha, too, to face evening after evening without him and without Pasha, to face war, to face herself without Alexander and without Pasha filled Tatiana with such a pervasive emptiness that she nearly groaned out loud, right in front of the laughing Anton and Kirill.

She needed just one thing now—to lay her eyes on the boy who had breathed the same air as her for seventeen years, in the same school, in the same class, in the same room, in the same womb. She wanted her friend and her twin back.

Tatiana thought she could feel Pasha while sitting out on the roof under the darkening sky; the white nights had ended on July 16. Her brother was not harmed. He was waiting for Tatiana to come for him, and she would not fail him. She wasn’t going to be like the rest of her family, sitting around, smoking, fretting. Doing nothing. Tatiana knew: five minutes with Pasha’s light heart and she would forget much of the last month.

She would forget Alexander. And she needed to do something to forget Alexander.

After everyone had gone to bed, Tatiana went downstairs, got a pair of kitchen scissors, and began to mercilessly lop off her blonde hair, watching it fall in long strands into the communal sink. Afterward the small, grimy mirror showed only a vague reflection. All she saw was her sulky lips and her sad, hollow eyes that glowed greener without the hair to frame her face. The freckles on her nose and under her eyes stood out even more prominently. Did she look like a boy? All the better. Did she look younger? More frail? What would Alexander think of all her hair gone? Who cared? She knew what he would think. Shura, Shura, Shura.

Just as dawn was breaking, Tatiana put on the only pair of beige trousers she could find, packed some baking soda and peroxide for her teeth, her toothbrush—she never took trips without her toothbrush—retrieved Pasha’s sleeping bag from his old days at camp, left a one-sentence note for her family, and set out for Kirov on foot.

During her last morning at work Tatiana was assigned to the diesel engines. She screwed the glow plugs into the combustion chambers. The plugs warmed up the compressed air in the cylinders before ignition could take place. She was very good at that part of the assembly, having performed it many times before, so she did her job mindlessly, while all morning struggling with her nerve.

At lunchtime she went to see Krasenko, bringing a willing Zina along, and told him they both wanted to join the People’s Volunteer Army. Zina had talked about joining the volunteers for over a week.

Krasenko told her she was too young.

She persisted.

“Why are you doing this, Tania?” Krasenko asked with sympathy in his voice. “Luga is not for a girl like you.”

She told him she knew how hopeless things were there. The bulletin boards at work shouted, “At Luga—to the trenches!” She said she knew that boys and girls of fourteen and fifteen were working in the fields digging trenches. She and Zina wanted to do all they could to help the Red Army soldiers. Zina nodded mutely. Tatiana knew she needed special dispensation from Krasenko. “Please, Sergei Andreevich,” she said.

“No,” he said.

Tatiana persisted. She told Krasenko she would take leave that was due to her, starting tomorrow, and get down to Luga one way or another if she had to. She was leaving, with or without his help. Tatiana was not afraid of Krasenko. She knew he liked her. “Sergei Andreevich, you can’t keep me here. How would it look if you were keeping eager volunteers from helping their motherland, helping the Red Army?”

Zina stood nodding by Tatiana’s side.

Krasenko sighed heavily and wrote them both passes and permissions to leave Kirov and stamped their domestic passports. As they were about to leave, he got up and wished her luck. Tatiana wanted to tell him she was going to go and find her brother, but she didn’t want him to talk her out of it, so she said nothing except thank you.

The girls went to a dark, gymnasium-size room, where after a physical exam they were outfitted with pickaxes and shovels that Tatiana found much too heavy for her, and were then sent to Warsaw Station on the bus to catch the special military truck transportation destined for Luga.

Tatiana wondered if they were going to be armored trucks like the ones that transported paintings from the Hermitage or like the ones that Alexander said he sometimes drove to the south of Leningrad.

They weren’t. They were just regular trucks covered with khaki tarpaulin, the kind Tatiana saw constantly around Leningrad.

Tatiana and Zina climbed aboard. Forty more people piled in. Tatiana observed the soldiers loading crates onto the truck. They would have to sit on them. “What’s in them?” she asked one of the soldiers.

“Grenades,” he replied, grinning.

Tatiana stood.

The trucks left Warsaw Station in a convoy of seven and started down the highway, bound south for Luga.

In Gatchina everyone was told to get off and take a military train the rest of the way.

“Zina,” Tatiana said to her friend, “it’s good we’re taking the train. That way we can get off in Tolmachevo, all right?”

“What are you, crazy?” said Zina. “We’re all going to Luga.”

“I know. You and I will get off, and then we’ll get back on another train and go to Luga.”

“No.”

“Zina, yes. Please. I have to get off in Tolmachevo. I have to find my brother.”

Zina stared at Tatiana with incredulity. “Tania! When you told me Minsk had fallen, did I say to you, come with me because I have to find my sister?” she said, her small, dark eyes blinking, her mouth tight.

“No, Zina, but I don’t think Tolmachevo has fallen to the Germans yet. I still have hope.”

“I’m not getting off,” Zina said. “I’m going like everybody else to Luga, and I’m going to help our soldiers, like everybody else. I don’t want to get shot by the NKVD as a deserter.”

“Zina!” Tatiana exclaimed. “How can you be a deserter? You’re a volunteer. Please come with me.”

“I’m not getting off, and that’s it,” Zina said, turning her head away from Tatiana.

“Fine,” said Tatiana. “But I’m getting off.”

4

A corporal stuck his head into Alexander’s quarters and shouted that Colonel Stepanov wanted to see him.

Colonel Stepanov was writing in his journal. He looked more tired than he had three days ago. Alexander patiently waited. The colonel looked up, and Alexander saw black bags under his blue eyes and taut lines in his face effected by the exertion of his will upon unwilling subjects.

“Lieutenant, sorry it took me a while. I’m afraid I don’t have much good news for you.”

“I understand.”

The colonel looked down into his journal.

“The situation in Novgorod was desperate. When the Red Army realized the Germans were surrounding the nearby villages only kilometers away, they recruited the young men from several camps around Luga and Tolmachevo to help entrench the town. One of those camps was Dohotino. I don’t know specifically about a Pavel Metanov…” The colonel cleared his throat. “As you know the German advance was much faster than we anticipated.”

It was Soviet-speak. It was like listening to the radio. They said this, but they meant that.

“Colonel? What?”

“The Germans got past Novgorod.”

“What happened to the young boys from the camps?”

“Lieutenant, beyond what I already told you, I don’t know.” He paused. “How well did you know this boy?”

“I know his family well, sir.”

“A personal stake in this?”

Alexander blinked. “Yes, sir.”

Colonel Stepanov was very quiet, playing with his pen, looking at the pages in his journal, not looking at Alexander, even when he spoke at last. “I wish I had something better to tell you, Alexander. The Germans ran over Novgorod with their tanks. Remember Colonel Yanov? He perished. The Germans shot soldiers and civilians indiscriminately, they pillaged what they could, and then they burned the town.”