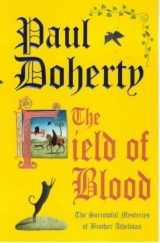

Текст книги "Field of Blood"

Автор книги: Paul Harding

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 13 страниц)

At last Athelstan glimpsed the sails of ships and smelled the fresh tangy air of the river. He was now in La Reole where the quacks, fortune-sellers and relic-sellers swarmed like the plagues of Egypt. He noticed with amusement one bold fellow screaming above the rest that he had Herod's foreskin for sale, skinned by a demon and placed in the cave above the Dead Sea. There was a small stall, guarded by two burly assistants, selling books and manuscripts. Athelstan would have loved to stop there. Such merchandise was very rare and Athelstan, who was determined to study the night sky before winter set in, was always keen on discovering some book on astronomy or astrology. Such manuscripts were now flooding into the country, brought by travellers from the East and hastily copied by scribes and scriveners. Nevertheless, he had to press on. Once darkness fell, the fisher of men would set sail on his barge.

Athelstan heaved a sigh of relief when he rounded a corner and saw the fisher of men sitting on a bench outside his chapel. He was surrounded by his strange crew, outcasts and lepers, their faces and hands bound in dirty linen bandages. Only one was different, a young boy called Icthus. He had no hair, eyebrows or eyelids and, with his protuberant eyes, pouting lips and thin-ribbed body, he looked like a fish and, indeed, could swim like one.

Very few people approached these men who combed the waters of the Thames for corpses. Outside the chapel was a proclamation bearing the charges for bodies recovered:

Accidents 3d. Suicides 4d. Murders 6d. The mad and the insane 9d.

The fisher of men rose as Athelstan approached.

'You have business with me, Brother?'

The fisher of men pulled back his cowl, his skulllike face bright with pleasure.

No one knew his origins. Some whispered that he was a sailor who had found his wife and children killed by marauders. He had lost his wits, wandered in the wastelands north of the city, before coming back to take up this most grisly position as an official of the City Corporation. He clapped his hands and a stool was produced from inside the chapel. The friar sat down.

'You wish to view a corpse?' the fisher of men asked. 'We have a fine array of goods today, Brother. A young man, deep in his cups, who tried to swim the Thames last night; a woman who threw herself off a bridge; a soldier from the Tower, as well as the usual collection of animals: five dogs, three cats, a sow and a pet weasel.' He grasped the skeletal arm of Icthus, his chief assistant. 'All plucked from the river by this child of God. And where is Sir John?' the fisher of men prattled on. 'The lord coroner does not visit me? I saw him today, coming out of Master Bapaume's, the goldsmith's.'

'It's good to see you sir,' Athelstan replied. 'And may Christ smile on you and your endeavours. Sir John and I are involved in certain mysteries.'

'And you need my help?'

'Yes sir, we need your help.'

The thin, bony hands spread out. Athelstan noticed how long and clean the nails were, more like talons than human limbs.

'We have costs, Brother. I have a family to keep; pleasures to make.'

'What pleasures?' Athelstan asked curiously.

The fisher of men leaned forward. 'I visit Old Mother Harrowtooth on London Bridge. She offers me relief.'

'Yes, yes, quite.' Athelstan opened his purse and took out a silver coin, one of those Bladdersniff had handed over.

The fisher of men's eyes gleamed but Athelstan held on to the coin.

'I want to tell you a story,' the friar continued.

'When you are holding a piece of silver, Brother, I don't care how long it is.'

'I am an assassin,' Athelstan began.

The fisher of men started rocking backwards and forwards with laughter. The rest of his crew joined

'I am an assassin,' Athelstan repeated. 'I am riding back through the fields of Southwark. I do not cross the bridge. Instead, I dismount somewhere opposite Billingsgate or even the Wool Quay, a fairly deserted spot. I am disguised and intend to cross the river by barge.'

'So, it's useless making enquiries among the boatmen?' the fisher of men broke in.

'Precisely. I cross hidden by the cloak and cowl I have brought with me.'

'But you have to get rid of the horse?' The fisher of men's thin lips parted in a smile. 'In Southwark, that would be easy enough. A horse left wandering by itself is soon taken. What else, Brother?'

'I don't really care if the horse is taken or not,' Athelstan explained. 'But its harness and housings?'

'Ah, I see.' The fisher of men smiled. 'That must not be discovered. Very difficult to hide eh, Brother? So, if I were an assassin, I would go out somewhere along the mud flats and throw it into the river. If I understand you correctly, you wish us to search for it? A heavy saddle would sink and lie in the mud. However, it might take months before it was completely covered over.'

'Can you do it?'

'Before darkness falls: Brother, our barge awaits.'

'There is one other matter,' Athelstan persisted.

'The Paradise Tree?' The fisher of men spoke up. 'I know your business, Brother. The good tavern-owner, Kathryn Vestler, stands trial for her life. I cannot believe the stories. A kindly woman who has shown us and others great charity. She has given the Four Gospels the right to pitch camp and await the coming of St Michael and his angels.'

His words provoked laughter among his coven.

'They'll have to wait long,' he continued. 'We often see the beacon fire they light upon the bank. On dark nights when the moon is hidden, it gives us bearings.'

'I am not really interested in them,' Athelstan said. 'True, Brother, madcaps the lot of them. The sounds we hear from their camp site are strange to say the least.'

'In your travels,' Athelstan chose his words carefully, 'especially at night, sir, you and your crew must see certain sights? Barges which have no lanterns, men masked, hooded and cowled?'

The fisher of men stared coldly back.

'Brother, I cannot tell you what happens along the Thames at night. We go unarmed. Oh, we carry an arbalest, a sword and a spear but we are left alone because we leave others alone.'

Athelstan sighed and got to his feet. He handed over the silver coin.

'But I can trust you on this matter?'

The fisher of men shook Athelstan's hand. The friar was surprised at the strength of his grip.

'You and Sir John are my friends. I have taken your silver. I have clasped your hand.'

Athelstan thanked them and went down towards the riverside where he hired a barge to take him across the now choppy Thames.

Athelstan dozed in the wherry then made his weary way along the valleys and runnels, passing the priory of St Mary Overy. All around him Southwark was coming to life at the approach of darkness. Taverns and ale-shops were opening; candles glowed in the windows. Dark shadows thronged at the mouths of alleyways or in doorways. Young bloods from the city, mice-eyed, heads held arrogantly, traipsed through their streets, thumbs stuck in their war belts: bully-boys looking for trouble, cheap ale and a fresh doxy.

Athelstan hated such men. They came from the retinues of the nobles at Westminster to seek their pleasures. Fighting men, skilled with sword and dagger, they could challenge the like of Pike in his cups to a fight and, in the twinkling of an eye, stick him like a pig.

He passed the Piebald and sketched a blessing in the direction of Cecily the courtesan, dressed in a low, revealing smock, her hair freshly crimped, a blue ribbon tied round her throat.

'You'll get up to no mischief, Cecily?' Athelstan called out.

'Oh no, Brother,' she answered sweetly. 'I'll be good all evening.'

Athelstan smiled and made his way up the alleyway. The church forecourt was deserted and he sighed in relief. However, as he went down the side of the church towards his house, two figures came through the lych gate of the cemetery.

'Oswald Fitz-Joscelyn! Eleanor! What are you doing here?'

The young lovers looked rather dishevelled, bits of grass clung to Eleanor's dress and she had a daisy chain around her neck. The young man, sturdy and broad, with a good honest face, laughed and shook his head.

'Brother, we may have been lying down in the grass but we were talking to Godbless.'

Eleanor spoke up. 'Can we see you?'

Athelstan hid his disappointment at not being able to go in and relax.

'Of course! Of course!'

He took them into the kitchen. The fire was unlit but everything was scrubbed and cleaned: the pie on the table looked freshly baked. Beside it stood a small bowl of vegetables.

'Would you like to eat?' Athelstan offered.

'No, Brother.'

When the two young lovers sat down at the table Athelstan decided the pie could wait. The smiles had gone. Both looked troubled and Athelstan's heart went out to them. Oswald's hand covered Eleanor's; now and again he'd squeeze it.

'Brother, what are we going to do?'

'Trust in God, trust in me, say your prayers.'

'I can't wait.' Tears brimmed in Eleanor's eyes. 'Pike the ditcher's wife, her tongue clacks. All the parish know about your visit to the Venerable Veronica.'

'I'm sorry,' Oswald broke in. 'I know, Brother, you have troubles of your own: Mistress Vestler has been taken by the bailiffs.'

'Do you know her?'

'Oh yes. A generous woman, well-liked and respected among the victuallers. My father buys wine from her, the best claret of Bordeaux.'

'But what about your troubles?' Athelstan asked.

'What happens,' Eleanor enquired, 'if we do lie in the grass and become one? What happens if I become pregnant?'

'I cannot stop you doing that,' Athelstan replied coolly.

'They couldn't do anything about it then.' 'No, they couldn't.'

'Why do we have to be churched to be married?' she insisted.

'When a man and woman become one, they imitate the life of the Godhead. God is present. Such a sacred occasion must, in the eyes of the Church, be blessed, and witnessed, by Christ Himself.' 'But Christ will be with us?'

'Christ is always with you,' Athelstan assured her. 'But will you be with Him?'

'Brother!' Eleanor lowered her head.

'Listen.' Athelstan stretched across the table and touched both of them. 'Just trust me. Wait a while, don't do anything stupid, something you'll regret. Love is a marvellous thing, it will always find a way. You may not believe this but God smiles on you, help will come.'

Eleanor's face softened.

'Please!' Athelstan pleaded. 'For my sake!'

The two young lovers promised they would.

'Now, go straight home!' Athelstan warned as they opened the door. 'You will go straight home, won't you?'

'Brother, we have given our word.'

They closed the door behind them. Athelstan put his face in his hands.

'Oh friar,' he murmured. 'What happens if they can't trust you? What happens if they shouldn't?'

'Evening, Brother. Talking to yourself? You must want company?'

The friar took his hands away. 'Come in Godbless, there is enough pie for two.'

After the meal was finished, Athelstan left Godbless to clear up the kitchen. He took the keys and went across to the church intent on going up the tower, sitting there and studying stars. He'd revel in their glory, let their sheer vastness and majesty clear his mind. He had the key in the church door when he heard the scrape of steel and whirled round. There were five in all, masked and cowled, the leader standing slightly forward from the rest. He wore a red hood and a blue mask with slits for his eyes, nose and mouth.

'Well, good evening, Brother Athelstan.' The voice was taunting. He gave the most mocking bow. 'Off to study the stars, are we? Perhaps I should join you, it's the nearest I'll get to heaven.'

Athelstan felt behind him and turned the key in the lock. If necessary, he would flee into the church then lock and bar the door behind him.

'You know me?' Athelstan tried to control his fear.

'I understand your good friend the coroner, Sir John Cranston, wishes words with the vicar of hell?'

Athelstan relaxed. He had met this reprobate before and knew he posed no danger.

'Why do you come with swords and clubs?' Athelstan asked. 'I walk your streets daily.'

'So you do, Brother.' The vicar of hell resheathed his sword. 'Whether it be a visit to an alehouse or those strange creatures at the Barque of St Peter.'

He took off his mask and pushed back his hood, revealing a tanned, sardonic face and oiled black hair, tied in a queue behind. A pearl dangled from one ear lobe, his clean-shaven face had soft, even girlish features, except for the wry twist to the mouth and those ever-shifting eyes.

'We always have to be so careful with Sir Jack. I mean, here I am, Brother, a former priest, a sometime Jack-the-lad at whose feet all the crimes in London are laid.'

'Cranston's a man of honour,' Athelstan retorted. 'One day, sir, he'll catch you and you'll hang.'

'Oh no, I won't, Brother: that's why I brought my boys along, just in case old Jack stands hidden in the shadows with some archers from the Tower. I understand you've been there.' He turned and looked over his shoulder. 'Guard the alleyway,' he ordered softly. 'Let anyone come and go. But, if there's any sign of danger, give the usual signal. Brother Athelstan, shall we go into church?'

The shadowy figures behind the vicar melted into the darkness. Athelstan turned the key and went in. He led his unexpected visitor up the nave and into the sanctuary where he lit every available candle. The vicar of hell made him open the sacristy and the narrow coffin door which led into the cemetery.

'Just in case,' the rogue grinned, clapping Athelstan on the shoulder, 'I have to leave a little more speedily than I came.'

He sat down on the altar boys' bench but kept his head back, hidden in the dancing shadows.

'I was a priest once, Athelstan.' The vicar picked up the little hand bell. 'How does it go?' He rang the bell. 'Three times for the sanctus.' He rang it again. 'One to warn the faithful that the consecration is near.' Once more he shook the bell. 'Three times for the host; three times for the chalice and finally for communion: Agnus Dei, Qui tollis peccata mundi …'

'Don't blaspheme!' Athelstan protested.

'I am not blaspheming, Brother. Just remembering. I would have been a good priest. Like you. Ah, but the lure of the flesh, the world and the devil. Anyway, I like your church. You certainly have built a parish here, Brother. I remember the previous incumbent, William Fitzwolfe. Now, he was a wicked bastard!'

'Why have you come?' Athelstan sat on the altar steps facing him.

'Sir John wants to see me.'

'Then go and visit him yourself.'

The vicar of hell laughed. 'What is it you want, Brother? And I'll be gone.' He opened his purse and shook out some coins.

'I don't want your money.'

'Take it as an offering and tell me what you want.'

'Alice Brokestreet,' Athelstan began. 'She worked in a tavern, the Merry Pig, which is also a brothel.'

'I know it well. She stabbed a clerk with a firkin-opener, pierced him dead. A foul-tempered woman! Now I understand she'll see Mistress Vestler hang.'

'You know of the incident?'

'I was there when it happened, it was murder.'

'And Mistress Vestler?'

'A secretive one, our tavern-mistress: keeps herself to herself. I approached her on one occasion.' 'For what?'

'To see if we could do business together, moving goods around London. Perhaps hire one or two of my girls for her house but she refused.'

'And you know nothing of a barge which comes down the Thames at night and moors on the mud flats near the Paradise Tree?'

The vicar of hell laughed softly.

'The river is not my concern, Brother Athelstan: it belongs to people like the fisher of men. In my new vocation, friar, you have to be careful you do not tread on other people's toes. It's the only way you keep alive. However, I'll tell you one thing, I give it to you free: the corpses found in Black Meadow? Bartholomew Menster?' The vicar of hell clicked his tongue. 'Now, Bartholomew was a clerk, a royal official, yet he approached one of my associates. He asked what price would he pay if a large chunk of solid gold came into his possession!'

'What?' Athelstan leaned forward.

'Oh, it's common enough, Brother. Stealing a cup, a jewelled plate, a chalice or a pyx. You can't very well go down to a goldsmith and hand it over. The same goes for a slab of pure gold. Questions will be asked! It's treason to take treasure trove and not declare it to the Crown.'

'And Bartholomew Menster asked this? When?'

'Oh, at the beginning of June.'

'But the gold was never produced?'

'We were very interested but there's an eternity of difference between talk of gold and actually owning it.'

Suddenly, on the night air, came a sharp, piercing whistle. Athelstan jumped to his feet and went to the mouth of the rood screen.

'Pax et bonum,Brother,' came the whisper.

Athelstan turned but the vicar of hell had gone.

'Pax et bonum,'Athelstan replied. 'May Christ smile on you.'

He went and locked the coffin door and the sacristy and walked down the church. Godbless and Thaddeus were sitting on the steps. The beggarman stared up at him.

'I thought I heard a commotion, Brother, so I came out.'

'Nothing,' Athelstan replied. 'Nothing but shadows in the night, Godbless.' 'Are you well, Brother?'

Athelstan started. Benedicta came out of the alleyway, a lantern in one hand, in the other a linen parcel wrapped in twine.

'I've baked some bread,' she said.

'You shouldn't be out,' Athelstan replied.

'I was restless.' She pulled back her cloak. Athelstan glimpsed the Welsh stabbing dirk in her belt. 'I have friends in Southwark, no one would lift a hand against me.'

Athelstan went across to his house. He had given up any idea of studying the stars. Godbless had cleared the kitchen table and the lord of the alleyways was now stretched out before the fire-grate. Athelstan put the bread in the small buttery. He filled three cups of ale and shared them out.

'Why are you restless?' he asked.

'For poor Eleanor's sake.' Benedicta chewed her lip. 'It's so sad to see someone so young, so deeply in love.' She smiled. 'I understand you went to see Veronica the Venerable?'

'Ah yes.' Athelstan went to fetch the grimoire from his chancery bag. 'She had this, a relic from William Fitzwolfe, our former priest.'

Benedicta leafed through the pages.

'You can have it,' Athelstan told her. 'Take it over to the parchment sellers in St Paul's and you'll get a good price for the cover. In the meantime, Godbless, Benedicta, I want you to do a job for me.' He emptied the contents of the bag out on to the table, opened an inkpot and scratched a short message on a piece of parchment. 'Go down to London Bridge. If you can, collect Bladdersniff on the way, I want you to go to the gatekeeper.'

'The mannikin Robert Burdon?'

'Yes, that's the one. Give him this message. Ask him to think carefully then come back to me. He must tell the truth.'

Benedicta looked at the scrap of parchment, shrugged and, with Godbless and Thaddeus escorting her, left the house. Athelstan watched them go then closed and locked the door behind them. He went and sat back at the table.

'Right, friar.' He sighed. 'There's no rest for the wicked and that includes you.'

Bonaventure lifted his head then flopped down again. Athelstan wrote down his conclusions on the murder of Miles Sholter and the two other unfortunates.

'Very clever,' he said to himself. 'It's true that the sons and daughters of Cain are more cunning in their ways than the children of the light. But, saying it is one thing, proving it another.'

He wrote a title on a scrap of parchment: the Paradise Tree. Bonaventure jumped on to the table.

'You've come to listen, have you? We have a tavern-owner, Bonaventure.'

The cat nudged his hand and Athelstan stroked Bonaventure's good ear.

'We know she is a good victualler and what else? A widow. She allows those Four Gospels to camp on her land. She is undoubtedly innocent of the deaths of those other remains. They are simply the skeletons of poor people who died in the great pestilence. But!' He spoke the word so loudly Bonaventure started. 'We have Bartholomew Menster and Margot Haden! They were undoubtedly killed on her land, either in the tavern itself or in Black Meadow. Their corpses were hurriedly buried. Why?' Athelstan closed his eyes. Gold! He thought: Bartholomew believed Gundulf's treasure was hidden in the church or chapel beside the Tower. It was a treasure which shone like gold. Bartholomew also made a reference, which I can't trace, something to do with the treasure shining like the sun buried beneath the sun. So, that means there's a scrap of parchment, some piece of evidence missing, probably destroyed. Athelstan wrote down other conclusions.

Item – How could Bartholomew and Margot enter Black Meadow without Kathryn Vestler knowing?

Item – Was Kathryn Vestler jealous of Margot Haden?

Item – Bartholomew had offered to buy the Paradise Tree. Why? To search for gold? Or had Mistress Vestler already found it and decided to silence Bartholomew and his paramour? After all, if Bartholomew knew the gold had been found, he could blackmail Mistress Vestler over not revealing treasure trove to the Barons of the Exchequer.

Item – Why had she burned Margot Haden's possessions?

Athelstan lifted his head. 'We know nothing about the dead girl,' he said. 'But I wager Master Whittock does.'

Athelstan returned to his writing. What were those black shapes and shadows glimpsed by the Four Gospels? What had they to do with Mistress Vestler? Athelstan paused.

'I am missing something,' he whispered. 'Master Cat, I am missing something but I can't remember what.'

Bonaventure yawned and stretched. Athelstan went into the buttery and brought back a small dish of milk and the remains of the pie. He put these down near the hearth and watched as Bonaventure delicately sipped and ate. The friar sat in the chair and closed his eyes. What was missing? Something he had learned? Athelstan rubbed his arms. If matters don't improve, he thought, Mistress Vestler will hang and that will be the end of the matter.

'It's this gold!' Athelstan declared loudly. 'These legends about Gundulf's treasure!'

He remembered the accounts book Flaxwith had taken from the Paradise Tree. He took a candle from the table and sat, going through the dirty, well-thumbed ledger. The accounts were a few years old. He could tell from the different entries that they marked the year Kathryn Vestler became a widow. There were Mass offerings made to a local church for her husband's requiem as well as regular payments to a chantry priest to say Mass for the repose of the soul of Stephen Vestler. Items bought and sold. Athelstan turned to the front of the ledger and noted the date 1374 to 1375. He studied the last page and whistled softly at the profits the Paradise Tree made, hundreds of pounds sterling.

'I am sure Master Whittock's found the same,'

Athelstan mused. 'And how can Kathryn explain such profits?'

He went through the items bought. A number of entries chilled his blood. Margot Haden was apparently a favourite of Mistress Kathryn. A list of expenses showed cloaks, caps, gowns and petticoats, shoes, belts and embroidered purses bought for the young chambermaid. At one item Athelstan closed his eyes.

'O Jesu miserere!'he prayed.

He picked up the ledger, holding it close to the candlelight, and read the item aloud.

'For a Book of Hours, bought for the said Margot Haden, so she could recite her prayers and make her own entries.'

Athelstan threw the ledger down on the floor. He was sure the documents Whittock had seized would show similar entries. How could Kathryn Vestler explain why she had burned what she described as 'paltry items'? A Book of Hours? Hadn't Kathryn Vestler really destroyed important evidence which, in any court, would surely send her to the scaffold?

Chapter 11

'Ecce Agnus Dei. Ecce qui tollis peccata mundi:Behold the Lamb of God, behold Him who takes away the sins of the world!'

Athelstan stood with his back to the altar and lifted the host above the chalice. He was celebrating a late Mass and most of his parishioners were present, huddled in the entrance to the rood screen. Athelstan turned back to the altar. He ate the host and drank from the chalice.

'May the body and blood of Christ,' he whispered, 'be not to my damnation but a source of eternal life.' He closed his eyes. 'Help me Lord,' he prayed. 'Make me as innocent as a dove and as cunning as a serpent. Send Your spirit to guide me. I thank You for the great favour You have shown.'

Athelstan could have hugged himself. He'd fallen asleep in the chair and woken in the early hours of the morning to see the scrap of parchment Benedicta had kindly pushed under the door. Master Burdon had told the truth. Athelstan, for the first time, could see a path through the tangle of troubles besetting him.

He heard a commotion at the back of the church and looked round. The fisher of men had entered with his strange coven around him. This caused consternation among the parishioners. The fisher of men was much feared, regarded as an outcast, and the members of St Erconwald's hastened to move away. Athelstan, however, continued with the Mass. He brought the ciborium down and distributed the hosts. He then went out into the nave and held a host up before the fisher of men.

'Ecce Corpus Christi!Behold the Body of Christ!'

The fisher of men's eyes filled with tears.

'We are not worthy, Brother.'

'No man is,' Athelstan said. 'Ecce Corpus Christi!''Amen!'

The fisher of men closed his eyes and opened his mouth. Athelstan put the host on his tongue. He then moved round the other members of the coven. Some objected. Athelstan felt a deep compassion for these most wretched of people, their eyes and mouths ringed with sores. He walked back to the altar and finished the Mass. However, he did not return to the sacristy but stood on the top of the altar

'The fisher of men,' he told his congregation, 'is my guest.'

'Brother.' Watkin spoke up. 'They search for the dead and …'

'Do their job well, Watkin, just like you sweep the streets of Southwark.'

'They are ugly,' Pernell the Fleming woman objected.

Athelstan, looking at her garish hair, thought he had never seen such a clear case of the pot calling the pan black.

'God does not think they are ugly,' Athelstan replied. 'All He sees are His children.'

A murmur of dissent greeted his words.

'They are our guests,' Athelstan urged. 'Now go, the Mass is ended!'

He went into the nave of the church where the fisher of men sat with his back to one of the pillars, his motley crew around him.

'Would you like something to eat or drink?' Athelstan asked.

'No, Brother, what you did and what you said is good enough.' The fisher of men's skull-like face broke into a grin; he grasped the shoulder of young Icthus who stared, fish-like, his cod mouth protuberant. 'Go on boy,' the fisher of men said. 'Show what we found.'

The parishioners on the other side of the church watched anxiously. Icthus skipped down the nave and Athelstan saw a bundle just inside the doorway covered with a canvas sheet. It was still dripping wet. Icthus picked it up and placed it at Athelstan's feet. When the fisher of men triumphantly plucked the sheet away Athelstan gazed down at a dirty, mud-slimed saddle, beneath whose heavy leather horn was the royal escutcheon. He turned the saddle over, and saw burned on the leather beneath, the letters M. S.

'Miles Sholter!' he breathed. 'This is a royal messenger's saddle!'

'And, Brother, look in the pouch.'

The friar turned the saddle back over, his hands and cuffs now soaked with the dirty river water. The fisher of men tapped the small leather pouch tucked into the saddle.

'Go on, Brother!'

Athelstan dug his fingers in. He could have cried 'Alleluia! Alleluia!' at what he felt. He took out the large St Christopher medal and couldn't resist doing a small dance of joy. His parishioners flocked closer, now seriously concerned about their little priest's wits.

'Is everything all right, Brother?' Pike glared at the fisher of men.

'Pike!' Athelstan exclaimed. 'God forgive you, but sometimes you are a great fool! And the same goes for all of you!' He grasped the fisher of men's shoulder. 'I prayed for deliverance. Oh, it's true what scripture says: "Angels come in many forms. This man has delivered us. Yea!".' Athelstan quoted from the psalms. ' "From the pit others had dug for us!" We will not have to pay a fine!'

That was it for the parishioners. Led by Benedicta, they streamed across the nave, thronging around the fisher of men, clapping him on the shoulder. Merry Legs, the pie shop owner, loudly proclaimed that each of them should receive the freshest and sweetest of pastries. Joscelyn the taverner, not wishing to be outdone, said he'd broach a fresh cask of ale. Athelstan had never seen a church empty so quickly. The fisher of men and his coven were bundled through the door, the parishioners loudly singing their praises, though they were still in doubt as to what miracle these strange creatures had wrought. Crim came speeding out across the sanctuary but Athelstan caught him by the shoulder.

'Crim!' He fished under his robes and took a penny from his purse. 'Merry Legs will keep a pie for you. Benedicta, bring the fisher of men back here.'

The widow woman hurried out and returned with their unexpected visitor.

'Where did you find it?' Athelstan asked.

'There's nothing the river can hide from us, Brother. In the reeds opposite Botolph's Wharf. I would wager someone went into the mud and threw it as far as they could. However, the silt and the weeds at the bottom caught and held it fast. Whoever did it must have been in a hurry'

'Oh yes they were,' Athelstan agreed. 'And now they can hurry to the scaffold and answer to God. Benedicta, see to our guests. Crim, go to Sir John Cranston. He is to bring his bailiffs and meet me outside Mistress Sholter's house in Mincham Lane. Now go, boy! Benedicta will see that your portion of pie is kept.'

Athelstan disrobed, piling his vestments on a stool just inside the sanctuary. He gave Benedicta the keys of the church and asked her to clear up the sacred vessels, thanked the fisher of men again and hastened across to his house. Pike followed him over.