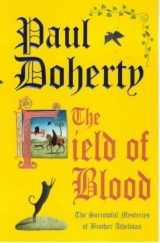

Текст книги "Field of Blood"

Автор книги: Paul Harding

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 13 страниц)

'Tell me what happened,' Athelstan began.

'Miles and Mistress Bridget live in Mincham Lane.'

'That's off Eastchepe?' Benedicta asked.

'We have a house there.' The young woman lifted her head. 'I am a seamstress, an embroiderer. I buy in cloth and sell it from a small shop below.' Her lower lip quivered. 'Miles and I had been married four years. He was well thought of. Why should anyone …?'

'Tell me what happened,' Athelstan repeated. He leaned across and patted the young woman on her hands.

'The day before yesterday,' Eccleshall replied, 'I went down to Westminster and received the Regent's letters for the Earl of Arundel. I then journeyed back to the royal stables in Candlewick Street where, by the Chancellor's writ, two horses and a pack pony were ready'

'What time was this?' Athelstan asked.

'After three o'clock in the afternoon. I then journeyed on to Mincham Lane. Miles was already waiting. He made his farewells and we travelled down Bridge Street across the Thames and through Southwark. A pleasant journey, Brother, no trouble. We decided to lodge for the night at the Silken Thomas.'

'Wouldn't you travel further?'

'No, once you get beyond Southwark the highway becomes lonely, rather deserted. Miles and I had decided to rest overnight and leave before dawn. By riding fast and changing horses, we could be in Canterbury by nightfall.'

'And nothing happened?'

'We arrived at the Silken Thomas. I hired a chamber while Miles took our saddlebags up. A simple, narrow room, two cot beds, the promise of a meal with bread and ale before we left in the morning. We must have stayed there about two hours. The sun was setting. I was dozing on the bed when Miles shook me awake. "Philip," he hissed. "I've forgotten my silver Christopher." Show him, Bridget.'

The young woman undid her purse and took out a silver chain with a medal of St Christopher hanging on it. The medal was large, about two inches across. Athelstan took it and studied it carefully. It weighed heavily, probably copper-gilt with silver.

'Miles had always been a royal messenger,' she explained. 'And, whatever the journey, he always took this with him. But, before he set off, he changed and left this on a stool in our bedchamber.'

'And he went back for it?' Athelstan asked.

'He wouldn't listen to me.' Eccleshall shook his head. "I'm going back," Miles said. "It won't take long." He put on his cloak and hood and went downstairs. I followed and said that I would wait for his return, he replied he wouldn't be long and galloped away.'

'And what happened then?'

'He never came home.' Mistress Sholter spoke up. 'But there again, Brother, I did not expect him. After Miles had left, I closed up the shop and went up to Petty Wales to buy some goods and provisions. I returned.' She fought back the tears. 'I thought Miles and Philip were safely on the road to Canterbury.'

'When he didn't return,' Eccleshall said, 'the next morning I travelled back into the city. I thought something had happened but, when I visited Mistress Bridget, she said she had not seen her husband. I then began my search. I heard rumours of corpses being found and came here.' He shrugged. 'I recognised Miles immediately but the other two I've never seen before.'

'And what was Miles wearing?' Athelstan asked. 'The same as me, Brother: a tabard, war belt, boots and cloak.'

'A strong man?'

'Oh yes, vigorous, a good swordsman.'

'So, if he was attacked, he would defend himself resolutely.'

'Brother, both Miles and I were soldiers.'

Athelstan paused and looked at the wall painting behind his visitors, depicting David killing Goliath.

'Let us say,' Athelstan began slowly, 'that Miles was attacked as he travelled back into Southwark. The first question is why?'

'He was a royal messenger, Brother. He wore the tabard and shield.'

'But why should someone attack him?'

Eccleshall shrugged. 'For any money he carried, his horse and weapons, not to mention the despatches.'

'But he wasn't carrying them that night, was he?'

'Oh no, Brother, I had them with me at the Silken Thomas.'

'Very well.' Athelstan played with the tassel on the cord round his waist. 'Had anyone a grudge against Miles? Was it possible that you were followed to the Silken Thomas and, when Miles left…?'

'No, Brother,' Bridget Sholter intervened. 'Miles was a merry soul. No one had a grudge or grievance against him.'

'So, it has to be put down to either robbery or treason?'

'It's possible. The Great Community of the Realm often attacks royal messengers.' 'And what happens then?' Eccleshall looked surprised.

'I mean,' Athelstan explained, 'are their bodies left in a hedgerow or a ditch?'

'No, Brother, they generally tend to disappear. So no one can take the blame.'

'I agree.' Athelstan moved on the bench. 'Now, Master Eccleshall, you are a soldier. I, too, have fought in the King's wars. Here we have a strong, well-armed young man riding his horse along the country lanes back into Southwark. You and I, Master Philip, are rebels. What do we do? We must get this man to stop and dismount.'

'One of us could lie down,' Eccleshall replied. 'Pretending to be injured.'

'But would you do that?' Athelstan asked.

'No, Brother, I wouldn't.'

'Of course not,' Athelstan retorted. 'It's a well-known trick and royal messengers, I understand, are under strict instructions to be wary of such guile and knavery. Miles Sholter was an experienced messenger, a soldier. Even if he was dismounted he would still be a powerful adversary. What I am saying, Master Eccleshall, is that Miles Sholter, if attacked by rebels or robbers, would first have been struck by an arrow.'

'It's possible, Brother, that his horse was brought down beneath him.'

'Yes, yes, I hadn't thought of that.'

'I understand your unease, Brother,' Eccleshall continued. 'But bailiff Bladdersniff said that Miles's corpse was found in a derelict house, an old miser's home in the middle of a field.'

'Yes, and that's the mystery. How did Miles get there? Where is his horse, his tabard, his war belt? And you see, Master Philip, we know that the two others, the whore and her customer, were killed because they surprised the slayer.'

'In what way, Brother?'

Athelstan rubbed the side of his head.

'I don't know. Sholter was apparently killed the day before yesterday, his corpse taken to that derelict house. The following evening the killer returns to strip it completely but he's surprised, so he slays his unexpected visitors.'

Athelstan tapped his foot on the floor. Bonaventure took this as a sign to jump in his lap and sat there purring.

'I'm intrigued,' Athelstan continued. 'Would robbers or rebels go to such lengths? Surely they'd drag poor Sholter off his horse, kill him and flee?'

'I disagree, Brother. Rebels would certainly hide the corpse and show little mercy to anyone who disturbed them.'

'Them?' Athelstan asked.

'It must have been more than one to attack a man like Miles Sholter.'

Athelstan caught the note of pride in Eccleshall's voice.

'And then to kill two more people. I've seen the corpses: both the whore and the other man were young, vigorous. They would have resisted, wouldn't they?'

Athelstan stared at the royal messenger: what Eccleshall said made sense.

'But you know what will happen?' the friar said quietly. 'The corpse of a royal messenger has been discovered in my parish, at a time when the shires round London seethe with unrest.'

'I'm sorry, Brother: what the Regent does is not my concern. I know a fine will be levied but you could argue the murder didn't take place here.'

'That's not the law!' Athelstan snapped. 'Master Eccleshall, Mistress Sholter, I grieve for your loss, I truly do. I shall remember Miles and the other victims at Mass. However, hideous murders have taken place! Blood cries to God for vengeance and, if I know the Lord Regent, justice will be speedily done. It has not been unheard of for Gaunt to hang people out of hand as a warning to others. Whoever killed those three unfortunates could have more blood on their hands.' He rose to his feet. 'If you learn anything at all?'

Eccleshall promised that he would return immediately. Athelstan gave them his blessing and they both left the church. Benedicta locked the door behind them.

'Is that safe?' Athelstan smiled. 'What if Pike the ditcher's wife comes? Benedicta the widow woman and the parish priest locked in the church?'

'Bonaventure's my escort,' Benedicta teased back.

Athelstan looked down at the cat; Bonaventure stretched, then padded over into the corner to search out the cause of certain sounds, only to return and stare up at his master.

'You are worse than a monk,' Athelstan teased. 'You know the hours and times for food.'

'What do you think?' Benedicta sat down on a bench.

'Benedicta, God forgive me, I am in God's house but what I say is the truth between the two of us. Miles Sholter, the preacher, and that pathetic young woman were murdered. I don't think Sholter was attacked by rebels or robbers. An arrow wound to the back or one loosed deep into the heart: that's the mark of the night people.'

'So what?' Benedicta asked.

'I don't know.' Athelstan shook his head. 'I sit in confession and listen to people's sins.' He paced up and down. 'I was taught by Prior Anselm to use logic and reason yet, at other times, it's good to forget these and listen to the heart.'

'Are you saying that Eccleshall and Mistress Sholter are assassins?'

Athelstan sat next to her on the bench.

'Listen Benedicta,' he said quietly. 'Here we have a young man, a royal messenger, happy and content. He leaves London and reaches a tavern. He finds he has forgotten his St Christopher medal and comes rushing back. On his way home he is brutally attacked and murdered, that would be Saturday evening. On Sunday his corpse is discovered in a derelict house by two people who are killed for their intrusion. All three corpses lie there until Luke Bladdersniff, our most industrious bailiff, finds them. Now, what's wrong with the theory that all three were killed by night-walkers?'

'Well. We know robbers or rebels do not act like that!'

'Good, Benedicta! Now we enter the realm of logic and evidence. Why should their corpses be kept? This is where the assassin, or assassins, made a mistake. I am sure Sholter's corpse would either have been destroyed by fire or hidden so it was never discovered. Matters, however, were complicated by the two intruders, so the assassin had to be careful. Hiding one corpse is relatively simple but three? The assassin, or assassins, returned on Sunday evening to finish their work with Sholter but the killing of the other two foiled that plan. Fire was the best solution but to burn a house requires oil and kindling. It's out in the countryside and such grisly preparations might be observed.'

'So, he was planning to return?'

'Possibly. When people were looking elsewhere for Sholter, the assassin, or assassins, would return, probably Monday evening, burning the house to the ground and consuming the corpses hidden inside. However, there's something more interesting. Tell me, Benedicta, when you leave your house what do you do?' He grasped her hand. 'Close your eyes. Tell me precisely what you do!'

'I put my cloak on. I make sure I am carrying my wallet, purse and belt. I check that there are no candles or fires left burning.'

'Good, honest woman.'

'I close the windows, lock the door and put the key in my wallet.'

'Go on!' Athelstan encouraged her.

'I am walking down the street. I am thinking about what I am going to buy. I am also worried about a certain meddlesome priest …' Benedicta rubbed her eyes. 'Who doesn't eat properly.'

'Terrible man,' Athelstan answered. 'But what else, Benedicta? What do you check?'

'That my key and any monies I carry are safe.' She laughed deep in her throat. 'The St Christopher medal!'

'Oh mulier foitis et audax,brave and bold woman,' Athelstan replied, quoting from the scriptures. 'You have said it, Benedicta! Here is a messenger leaving his young wife. He will stop at a tavern on Saturday evening and continue his journey on Sunday. He's riding through open countryside. He's well armed and protected: however, he's a young man who has a deep devotion to St Christopher and knows such journeys can be dangerous. Isn't it strange, Benedicta, that he never feels his neck for the chain, never realises it's missing until he reaches the Silken Thomas?' Athelstan held a finger to his lips. 'What he does next is both reasonable and logical. He hurries back but, surely, he wouldn't have forgotten it in the first place? And, even if he had, he must have noticed it was missing long before he reached the tavern?'

'There's only one flaw in your logic'

'I am sure there is. And it would take a woman to find it.'

'What if Eccleshall is telling the truth? What happens if Sholter deliberately left the medal behind to provide a pretext for returning home?'

Athelstan raised his eyebrows. 'Prior Anselm would like you. It's possible! Sholter, for some reason unknown to us, distrusts his pretty young wife so he goes to the tavern and decides to return. He rides through the night, reaches Mincham Lane where his wife is entertaining someone else. A quarrel breaks out. Sholter is killed.' He glanced at Benedicta. 'And what next, mistress of logic?'

'The corpse is put into a cart, covered or hidden, and taken out to that derelict house.'

'Now, that is possible. But a cart would be seen, it would leave marks. It has to be trundled through busy streets and why go there? Why not take it out through Aldgate, hide it in the wild countryside north of the Tower?' He tapped Benedicta on the nose. 'But I accept your reasoning. Yet I am certain either one, or both, of that precious pair are implicated in Sholter's murder.' He fought back his anger. 'For which this parish is going to pay.'

'There are other difficulties,' Benedicta pointed out. 'What if we can prove that Mistress Sholter stayed in her house on Saturday evening and Master Eccleshall never left that tavern?'

Athelstan got to his feet and clapped his hands at Bonaventure.

'That, my dear Heloise, would pose a problem!'

'Who's she?'

'A beautiful woman who fell in love with a priest called Abelard.'

'I've never heard of him,' she replied tartly.

'Come.' Athelstan walked to the door, Bonaventure trotting behind him. 'Let's feed the inner man.'

They left the church. Outside the day was dying. Athelstan expected to see some of his parishioners but, apart from Ursula the pig woman disappearing down the alleyway, her great sow trotting after her, ears flapping, the church forecourt was empty. Philomel was leaning against his stall busily munching.

Athelstan found his small house swept and cleaned, a fire ready to be lit. On the scrubbed table stood two pies covered with linen cloths and an earthenware jug of ale. Bonaventure went and lay down in front of the empty grate. Athelstan brought traunchers and goblets from the kitchen, horn spoons from his small coffer. He was about to say grace when there was a knock on the door and Godbless, followed by his little goat, bustled into the house. The beggarman was small, his hair dishevelled, eyes gleaming in his whiskered weatherbeaten face. Athelstan noticed the horn spoon clutched in his hand. Thaddeus went across to sniff at Bonaventure but that great lord of the alleyways didn't even deign to life his head.

'I am hungry, Brother.'

'Godbless, you always are. When you die we'll say you were a saint.'

Godbless looked puzzled.

'You can read minds,' Athelstan explained.

'I've been in the death house.' Godbless rubbed his stomach and looked at the pies. 'I've had some cheese and bread but I knew about these pies, Brother.'

'It's not the death house,' Athelstan reminded him. 'Pike and Watkin have built a new one and, from now on, you are to call your little house the "porter's lodge". You are the guardian of God's acre. I don't want Pike and Watkin getting drunk there or Cecily the courtesan meeting her sweethearts in the long grass. If I've told that girl once, I've told her a thousand times: only the dead are supposed to lie there.'

Godbless solemnly nodded.

'And I'm going to offer you a reward.' Athelstan gestured at him to sit. 'I have this dream,' the friar continued, pushing a trauncher towards the little beggarman. 'To actually plant vegetables which I, not Ursula's sow, will eat.'

'I've driven that beast off before, Brother.'

'Beast is well named,' Athelstan quipped. 'That pig fears neither God nor man.'

'I'm glad I'm here.'

Godbless watched as Benedicta cut the pie and held his trauncher out. Athelstan filled the earthenware cups with ale.

'That young woman in the cemetery, she is such doleful company!'

The friar nearly dropped the jug. 'What young woman?'

'You know, Eleanor, Basil the blacksmith's daughter. She's just sitting under a yew tree muttering to herself.'

Athelstan was already striding towards the door. Godbless happily helped himself to another piece of pie and began to eat as fast as he could. The friar, followed by Benedicta, hurried through the enclosure along the side of the church and into the cemetery where Athelstan climbed on to an old stone plinth tomb. It supposedly contained the bones of a robber baron who had been hanged and gibbetted outside St Erconwald's many years ago.

'What's the matter?' Benedicta asked.

'Eleanor!' Athelstan shouted. 'Eleanor! You are to come here!'

He glimpsed a flash of colour. Eleanor rose from where she was hiding behind a tomb, head down, hands hanging by her sides. She came along the trackway. Athelstan climbed down.

'Eleanor, what are you doing here?'

'I feel as if I want to die, Brother. I just miss Oswald but our parents will not allow us to see each other and it's all due to that wicked vixen's tongue.'

'You'll die soon enough. And then you'll go to heaven. In the meantime you've got to live your life. God has put you here for a purpose and that purpose must be fulfilled.'

'I feel like hanging myself.'

Benedicta put her arm round the young girl's shoulder and stared in puzzlement at the friar.

'She loves Oswald deeply,' Athelstan explained. 'But, according to the blood book, a copy of which we haven't got, they are related.'

'Ah!' Benedicta hugged the young woman close.

'Come back with me,' Athelstan suggested. 'Have some pie and ale. A trouble shared is a trouble halved.'

They returned to the kitchen. Godbless sat, his chin smeared with the meat and gravy, a beatific smile on his face.

'You are worse than the locusts of Egypt,' Athelstan complained. 'But, come, sit down.' He sketched a hasty blessing. 'Lord, thank You for the lovely meal and let's eat it before Godbless does!' Athelstan raised his cup and toasted Eleanor. 'Now, let me tell you what happened today because it will be common knowledge soon enough in the city.'

Athelstan half closed his eyes, his mind going back to Black Meadow: the Four Gospels, those shadowy shapes slipping in from the river at night and, above all, that dreadful pit and the skeletons and corpses it housed. 'Brother?'

Athelstan glanced at Benedicta. 'It's a tale of murder,' he replied. 'And, I'm afraid, before God's will is known, more blood will be shed!'

Chapter 6

Athelstan was up early the next morning. He celebrated a dawn Mass with Bonaventure as his only congregation. He tidied the kitchen, checked on Philomel, Godbless and Thaddeus while trying to make sense of what had happened the day before.

The business of Kathryn Vestler he put to one side. It was too shadowy, too insubstantial, but he still held to the conclusion he had drawn about the murder of Sholter and the other two. However, his real concern was Eleanor, Basil's daughter, and, when Crim appeared to serve as altar boy for his second Mass, he sent him round to members of the parish council. Afterwards Athelstan hastily broke his fast, went back to his bed loft and knelt by a chair to recite the Divine Office. He kept the window open and eventually heard the sounds of his parishioners arriving. He flinched at Pike's wife screeching at the top of her voice. He closed his eyes.

'Oh Lord, please look after me today as I would look after You, if Athelstan was God and God was Athelstan.'

He crossed himself. He often recited that prayer, particularly when he was troubled or anxious. Then he put away his psalter, climbed down from the bed loft and went out across to the church.

Athelstan always marvelled how his parishioners sensed some impending crisis. The whole council had turned up, eager to learn any tidbits of scandal and gossip. They all now sat in a semi-circle at the back of the church where he and Benedicta had met their two visitors the previous evening. The benches were neatly arranged, the sanctuary chair had been brought down for himself.

Of course there had been the usual struggle for positions of authority. Athelstan groaned at the way Pike's wife was glaring at Watkin's bulbous-faced spouse, for her expression suggested civil war must be imminent. Watkin, as leader of the council, sat holding the box which contained the blood book and seals of the parish. These were the symbols of his authority; the way Watkin gripped them and looked warningly at the rest from under lowered bushy brows reminded Athelstan of a bull about to charge.

Pike sat next to him. Hig the pigman, his stubby face glowering, looked ready to pick a quarrel with the world and not give an inch. Pernell the Fleming woman had tried to change the dye in her hair from orange to yellow. Athelstan tried not to laugh. The result was truly frightening. Pernell's hair now stuck up in the most lurid colours. Benedicta sat next to her, whispering to assuage the insult one of the rest must have levelled at the poor woman. Mugwort the bell clerk, Manger the hangman, Huddle the painter, eyes half-closed, and Ranulf the rat-catcher: from the huge pockets on his leather jacket Ranulf's two favourite ferrets, Ferox and Audax, poked out their heads. Cecily the courtesan wore a new bracelet and looked like a cat which had stolen the cream. Basil the blacksmith and Joscelyn from the Piebald tavern were also present. The door was flung open and Ursula the pig woman hurried in, her great sow trotting behind her. The ferrets sniffed the air and disappeared. The pig would have headed like an arrow straight into the sacristy but Ursula smacked its bottom and it sat down immediately. Athelstan looked daggers at the offended sow. If I had my way, he thought, I'd bring bell, book and candle and excommunicate that animal!

'We are ready, Brother,' Watkin announced sonorously. 'The council is in session.'

'Do you know what that means, Watkin?' Pike jibed.

'Shut your mouth!' Watkin's wife retorted. 'My man knows his horn book, he can make his mark. Unlike some of the ignorant…!'

'Thank you. Thank you,' Athelstan intervened. 'Remember we are in God's house. The Lord is a witness to what is going to happen. I do thank you all for coming.'

Before anyone could object, Athelstan made the sign of the cross and intoned the 'Veni Creator Spiritus'.He sat down.

'We are in session!'

'We need more sinners for the choir!' Mugwort spoke up: his remark immediately provoked roars of merriment. 'I mean singers,' he corrected himself.

'In St Erconwald's,' Athelstan said, 'it's the same thing. We are not here for singers.' He continued, 'You know the reason why. Eleanor, Basil's daughter, is deeply in love with Oswald, Joscelyn's son. They are both good young people. I hope to witness their vows here at the church door. We will have dancing, singing, church ales …'

'Aye and a lot of fun in the long grass in the cemetery!' Pike's wife snapped, glaring at Cecily.

'Why, is that what you do?' the courtesan answered in mocking innocence.

'However,' Athelstan continued remorselessly, 'we have a problem. The Church's law is very clear on this matter. You cannot marry within certain blood lines. It would appear that Basil and Joscelyn's great-grandmothers were sisters. Now, you know that, although we have a blood book, it does not go back to those years.'

'What years?' someone asked.

Everyone looked at the blacksmith.

Basil flapped his leather apron and folded his great muscular arms. 'I don't know.'

'It must have been in the time of the young King's great-grandfather, Edward II,' Athelstan put in.

'Wasn't he the bum-boy?' Mugwort asked, eager to show his knowledge. 'Didn't they kill him by sticking a hot poker up his fundament?'

'That's disgusting!' Watkin's wife exclaimed. 'Anyway, how could they put a poker …?'

'Listen,' Athelstan continued. 'We have a blood book but it doesn't go back that far. What we are missing …' He waved his hand. 'Well, you know the previous incumbent?'

'He was a bad bastard, Brother,' Pike said darkly. 'Dabbled in the black arts, out at the crossroads in the dead of night.'

'He was sinful and he was wicked,' Huddle added. 'He didn't like painting. He kept the church locked.'

'He also stole things,' Athelstan continued. 'And probably sold them for whatever he could, including our blood book.'

'Yet, what's the harm in all this?' foscelyn asked. He sat awkwardly, the empty sleeve, where he had lost an arm at sea, thrown over his shoulder, his other hand stretched out to balance himself. 'I mean, Brother, if they marry? Our great-grandmothers lived years ago, the blood line must be pure.'

'Not necessarily,' Pike's wife retorted. 'Things can still go wrong. We don't want monsters in the parish.'

'True, true,' Ranulf murmured. 'We have enough of those already.'

'How do we know they were sisters?' Athelstan asked. 'That's the reason for this meeting. Who will speak against me proclaiming the banns? You know what they are. I ask you formally. Who, here, can object to such a marriage taking place? It is a very grave matter. You must answer, as you will to Christ Himself.'

All eyes turned to Pike's wife.

'There is a blood tie,' she declared, adopting the role of the wise woman of the parish. Her voice became deeper, relishing the importance this proclamation gave her. Pike looked down and shuffled his feet.

'And what proof do you have of this?'

Athelstan's heart sank at the spiteful smile on the woman's face.

'Proof, Brother? No less a person than Veronica the Venerable.'

'Oh no!' Basil groaned.

'And you are sure of this?' Athelstan asked.

'Go and see her yourself, Brother. She may well be four score years and ten but her mind is still sharp and her memory good. I know the rules. If two witnesses speak out against a marriage, it cannot take place.'

Athelstan lowered his head. Veronica the Venerable was an ancient crone who lived in a tenement on Dog Tail Alley just behind the Piebald tavern. She claimed to be too old to come to church so Athelstan sometimes visited her. She was old, frail, but her mind was sharp. A cantankerous woman who had a nose for gossip and a memory for scandal, she had lived in Southwark for years and claimed she even watched Queen Isabella's lover Roger Mortimer being hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn some fifty years earlier.

'Why are you so hostile against the marriage?' Benedicta asked.

'Widow woman, I am not, I simply tell the truth!'

Aye, Athelstan thought, and you love the pain it causes. He saw the pleading look in Basil's eyes while Joscelyn just sat shaking his head.

'I will visit Veronica.' Athelstan tried to sound hopeful. 'I will make careful scrutiny of all this and perhaps seek advice from the Bishop's office. Now, there's another matter.'

Bladdersniff raised his head. His cheeks were pale but his nose glowed like a firebrand.

'The corpses?' he asked.

'I'll be swift and to the point,' Athelstan said. 'Three people were murdered in the old miser's house beyond the brook. God's justice will be done but, unfortunately for us, so will the King's. One of the victims was a royal messenger.' He paused at the outcry. 'You know the law,' Athelstan continued. 'Unless this parish can produce the murderer, everyone here will pay a fine on half their moveables. The King's justices,' he stilled the growing clamour with his hand, 'are sitting at the Guildhall. I have no doubt a proclamation will be issued. The fine would be very heavy.'

Athelstan felt sorry for the stricken look on their faces.

'It could be hundreds of pounds!' All dissension, all rivalry disappeared at this common threat.

'You know what I am talking about. The justices will rule that the royal messenger was killed by the Great Community of the Realm. By those who secretly plot rebellion and treason against our King.'

'It's not against the King!' Pike protested. 'But against his councillors!'

'Now is not the time for politicking,' Athelstan warned him, 'but for cool heads. We will not take the blame for these terrible deaths so keep your eyes and ears open. Sir John Cranston is our friend, he will help and we'll put our trust in God.'

Athelstan rose as a sign that the meeting was ended. He was angry at Pike's outburst but determined to use it.

'The day has begun,' he added softly, 'and I have kept you long enough. Thank you. Pike, I want a word with you.'

Athelstan walked up the nave and under the rood screen, Pike came behind shuffling his feet. He knew his outburst had angered his parish priest and he was fearful of the short and pithy sermon he might receive. Athelstan knelt on the altar steps. 'Kneel beside me, Pike.'

The ditcher did and stared fearfully up at the silver pyx hanging above the altar.

'Pike,' Athelstan began. 'We are in the presence of Christ and His angels.'

'Yes, Brother.'

'I know you are a member of the Great Community of the Realm but, if you ever make an outburst like that again, I'll box your ears, small as I am!' Athelstan glanced wearily at the ditcher. 'Don't you realise,' he whispered, 'if one of John of Gaunt's spies heard that, they could have you arrested.'

'I, I didn't mean

'You implied you knew the rebels, that's good enough.'

'I'm sorry, Brother.'

'Don't be sorry. Just keep your mouth shut and the same goes for Imelda. Young Eleanor is very angry. She spent last night crying.'