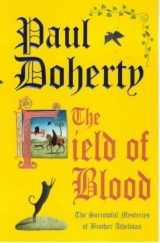

Текст книги "Field of Blood"

Автор книги: Paul Harding

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 13 страниц)

'Members of the jury!' he intoned. 'Look upon the prisoner. Do you find her guilty or not guilty as charged?'

'Guilty with no recommendation for mercy!' came the foreman's stark reply.

Kathryn Vestler swayed a little. Hengan hid his face in his hands. Sir John was wiping at his eyes but Athelstan, hands clasped, watched the piece of black silk being placed over Chief Justice Brabazon's skullcap.

'Kathryn Vestler,' he began. 'You have been found guilty of the hideous crime alleged against you. A jury of your peers has decided that you, maliciously and heinously, murdered Bartholomew Menster and Margot Haden. You claim you are a woman of good repute. The court does not believe this. We know of no reason why you should not suffer the full rigours of the law.' He paused. 'Kathryn Vestler, it is the sentence of this court that you be taken to the place from whence you came and confined in chains. On Monday next, at the hour before noon, you shall be taken to the lawful place of execution at Smithfield and hanged by your neck until dead, your corpse interred in the common grave. May the Lord,' Sir Henry concluded, 'have mercy on your soul! Bailiffs, take her down! Members of the jury, you are thanked and discharged!'

Kathryn Vestler was immediately hustled away. Athelstan heard the cat-calls and cries from outside as she was led to the execution cart. Sir Henry and all the retinue of the court formally processed out. Sir John sat, legs apart, hands on his knees, staring down at the floor.

'I am sorry, Stephen,' he muttered as if his dead friend could hear him. 'I am sorry but I could do no more.'

Hengan still sat on the lawyer's stool, pale-faced and sweating.

'Come on man!' Sir John called over. 'This is no time and place for tears!'

They left the Guildhall by a side entrance. A quack doctor came running up, offering a sure remedy for rotting of the gums.

'It's a distillation of sage water.'

But he saw the look on the coroner's face and, grasping his tray, scuttled away.

Sir John marched up Cheapside, Athelstan walking beside Hengan. Now and again he glanced sideways;

the lawyer looked truly stricken, lips moving wordlessly, dabbing at his sweaty face with a rag. He seemed unaware of the crowds, of the gentlemen and their ladies, the apprentices screaming for custom, the criers shouting for every household to keep a vat of water near the doorway in case of fire.

Sir John, also, was in no mood for distractions. Leif the beggarman came hopping over but Sir John raised a clenched fist and the beggarman hobbled away as if he, too, knew this was not the time for his importunate pleas.

Once inside the Holy Lamb of God Sir John sat down on the window seat and crossly demanded a meat pie and three blackjacks of ale. Athelstan found his throat and mouth dry. He could not believe what had happened. He leaned over and grasped Hengan's hand, which was cold as ice.

'You did your best, Master Ralph.'

'I wish I could do more,' the lawyer grated. 'I tell you this, Brother, I am Mistress Vestler's executor. Once I have refreshed myself, I am going to the Paradise Tree to search it from top to bottom. I'll find Gundulf's gold for you, Sir Jack, for old friendship's sake.'

'If you find it,' Sir John replied, lowering the blackjack, 'I'll seek an immediate audience with my Lord of Gaunt. I'll do that anyway. A stay of execution, a pardon? Who knows, they may even agree to Kathryn being hanged by the purse and leave it at that.'

'But you don't think so, do you?' Athelstan asked. Sir John shook his head. 'The murder was malice aforethought. Mistress Vestler refused to plead

guilty, while Bartholomew was a royal clerk. The Crown will not listen to pleas of mitigation.'

'How did Whittock know all that?' Athelstan asked.

Hengan was staring into his tankard. 'Ralph?'

'I'm sorry. I was thinking how the Crown must be pleased that Brokestreet is dead. After all, she was a condemned felon who killed a man with a firkin opener. Rumour will now place her death at Mistress Vestler's door. The gossips will argue that it was in her interests for Mistress Brokestreet to be killed; Kathryn had relationships with outlaws or smugglers and they did the bloody deed. I am sorry, Brother, I am confused. What I am really saying is any real plea for pardon will be turned down; Mistress Vestler will be regarded as a murderess on many counts. I must find that treasure.' He paused. 'Thesaurus in ecclesia prope turrem:I wonder what that means?' He smiled at Athelstan. 'I'm sorry, Brother, you asked a question?'

'How did Master Whittock know to call all those witnesses?'

'Oh, quite easy,' Sir John said. 'I've been thinking of that myself. The accounts books, eh Master Ralph?'

The lawyer nodded. 'The accounts books, Sir Jack, have a great deal to answer for. They'll show all the monies spent by Kathryn Vestler on Margot Haden, including pennies given to chapmen to deliver messages to her sister. The same will be true of the tree pruner and Master Biddlecombe. Whittock's clerks searched all these out.' He finished his tankard and got to his feet. 'Sir Jack, Brother Athelstan, today is Thursday: in three days' time Mistress Vestler hangs. I will see what I can do.'

Athelstan watched him go then became distracted by a beggarman who brought in a weasel for sale. Sir John threw the fellow a coin and told him to go away.

'There's little we can do, is there, Brother?'

'Sir Jack.' Athelstan got to his feet. 'You can pray and we can think.'

And, giving the most absentminded of farewells, Athelstan left. Sir John was so bemused, he had to call for a further blackjack of ale to clear his wits.

Meanwhile the little friar trudged down Cheapside. As he went he pulled his cowl over his head, pushing his hands up his sleeves.

'Isn't it strange?' he asked himself. 'Sir Jack and I.' He paused. Yes, that's why he was confused! He and the coroner hunted murderers down, sent assassins to their just deserts. Now he was desperately trying to free one.

Athelstan crossed London Bridge. He stopped halfway and went into the chapel of St Thomas a Becket where he sat in the cool darkness staring up at the sanctuary lamp. He found it hard to pray. His mind was all a-jumble: scenes from the court, the witnesses being called, raising their hands; Whittock's persistent questions; Brabazon's smile; the lowering looks of the jury men; Mistress Vestler standing poised but defiant. Athelstan crossed himself and left.

When he reached St Erconwald's the churchyard was empty but the door was open so Athelstan slipped inside. Huddle the painter was sitting dreamily on a stool. This self-appointed artist of the parish was determined, given Brother Athelstan's patronage, to cover every bare expanse of wall in the church.

'What's on your mind, Huddle?'

'The marriage feast at Cana. I have Eleanor and Oswald. Joscelyn can be the wine-taster. Benedicta can be Our Lady, Sir Jack would be one of the guests. Just think of it, Brother.'

'And what will Pike the ditcher's wife be?'

'Why, she will be Herod's wife.'

'Herod's wife didn't attend the marriage feast at Cana.'

'How do we know, Brother?'

Athelstan patted him on the shoulder.

'You have the key to the church?'

'Benedicta left it with me. She gave me a pot of the rabbit stew she made for you. It's in the kitchen. I also took some of the ale.'

'We are a truly sharing community,' Athelstan remarked.

He went and checked on Philomel. The horse lay so silently Athelstan wondered if it had died but it was only sleeping. In the cemetery Godbless was lying on one of the tombstones sunning himself, Thaddeus quietly cropping the grass beside him.

Athelstan tiptoed back. He found the house in order. Bonaventure was out and Athelstan sat in his chair next to the empty grate. Something troubled him. Something he had seen and heard this morning, but he kept it to one side. He recalled Master Whittock's questions, the line of witnesses he had summoned. Athelstan searched out the old accounts book. He sat at the table and leafed through the pages. Yes, it all made sense. Mistress Vestler was a good householder. She and her husband had kept meticulous accounts. Items purchased; guests who had called; alms given to beggars. He noticed the name of Biddlecombe the chapman, a regular visitor, often given a fresh bed of straw in the outhouse. Athelstan's eyes grew heavy and he was about to turn the page when one entry, a purchase by Kathryn's husband, caught his eye.

Chapter 14

Athelstan went through the ledger very carefully noting that there were other entries beside the two he had already discovered. He secretly admired their detail. No wonder the serjeant-at-law had been able to present such a compelling case. The suspicions which had nagged his mind now grew and took shape. Athelstan sadly reflected on the power of love: the damage, as well as the good, it could do. Time and again he went through the journal, only wishing he had the others to inspect. As the evening drew on Bonaventure came back and pestered him for food and milk.

'You are a riffler. Do you know that?' Athelstan lectured him. 'You prowl the alleyways and you come back in a bad temper.' He got to his feet. 'Bad-tempered cats, Bonaventure, will never enter the kingdom of heaven. If you are not a Jesus cat what hope is there for you?'

Bonaventure just rubbed himself against the friar's legs, arching his back, persisting in his demands until Athelstan fetched him a dish of milk. Huddle brought the key across and Athelstan went out to check that all was well. He was too tired to study the stars but retired early and fell asleep thinking about Kathryn Vestler manacled in the condemned cell and said a quick prayer for her.

The next morning Athelstan surprised Crim by taking out the special red vestments reserved for the feast of Pentecost: a beautiful chasuble with gold and silver crosses sewn on the back and front.

'We need God's help,' he told the heavy-eyed altar boy. 'I doubt if many of my parishioners are here this morning. It will take some time for the effects of all that revelry to wear off.'

Athelstan celebrated his Mass, praying that God would make him as innocent as a dove and as cunning as a serpent.

'Because, Lord,' he concluded, 'today justice must be done.'

Athelstan finished his Mass, hastily broke his fast then locked up the house and church. He hurried through the streets down to the riverside. Although he passed the occasional parishioner he kept his eyes lowered, unwilling to be distracted or drawn into conversation. The river mist still hung heavy but a taciturn Moleskin soon rowed him across the other side. The fish market was preparing to open as Athelstan landed on the quayside and hastened up through Petty Wales to the Paradise Tree.

The ale-master came out to meet him; he looked rather sheepish and rubbed his hands.

'I am sorry, Brother,' he mumbled as he led the friar into the taproom still not yet cleaned from the previous evening. 'But I had no choice. Master Whittock was most insistent.'

Athelstan took a seat near the window and looked out across the garden, savouring the early morning freshness. Sparrows squabbled in the trees; house martins dived and swooped over the flower beds, still covered with a crystal-white morning frost. Then he turned to the ale-master.

'Please bring me a cup of watered wine and some bread and cheese.'

The man hurried away. Now and again servants popped their heads round the door of the kitchen to study this little friar who had become so immersed in their mistress's affairs. Athelstan hoped Sir John would not be late. Before he had celebrated Mass, he'd despatched Godbless with an urgent message for the coroner to meet him here.

'The tavern will be closed on Monday,' the ale-master mournfully informed him. 'And what will happen then, eh, Brother?'

'I don't know. Was Master Hengan here yesterday?'

'Oh yes, sir, conducting the most scrupulous of searches.'

Athelstan thanked him and turned away. He heard a dog bark and Sir John's bell-like voice.

'For the love of God, Henry, keep that bloody dog away from me!'

Sir John, followed by Flaxwith and the ever-slavering Samson, walked into the taproom. The coroner clapped his hands and beamed around, but Athelstan could see he was pretending: he looked heavy-eyed, haggard-faced. He had not even bothered to change his shirt or doublet. He slumped down on the stool opposite Athelstan and threw his beaver hat on to the table.

'I don't know about you, Brother, but I will not be in London on Monday. Flaxwith!' He turned to his ever-patient chief bailiff. 'Join the rest and take Samson with you!'

'No, Henry.' Athelstan beckoned him over. 'I want you to do more than that. Take your lovely dog for a walk through Black Meadow. Tell the Four Gospels, those strange creatures who dwell in the cottage down near the river, that the lord coroner and Brother Athelstan wish words with them beneath the oak tree.'

Flaxwith went out. Sir John looked narrow-eyed at his companion.

'What's this, Brother?'

'Just drink your ale,' Athelstan replied.

The coroner obeyed but his impatience was apparent.

'Right!' Athelstan got to his feet. 'Come on, Sir John! I've got a few surprises for you.'

The garden was beautiful. Athelstan passed the sundial and noticed how its bronze face glittered in the early morning sunlight.

'First things first,' he whispered.

Cranston stopped at the lych gate leading to Black Meadow.

'What's this all about, Brother?'

'Walter Trumpington.'

Cranston furrowed his brow.

'Walter Trumpington,' Athelstan repeated. 'Doesn't the name ring a bell?'

'Well, yes, it does, that rogue, the First Gospel.' 'And Kathryn Vestler?' 'What about her, Brother?' 'What's her maiden name?'

'Oh, I don't know. She came from a village outside Cambridge. She and Stephen were married years …' Sir John's jaw sagged. 'It's not Trumpington, is it?'

'Yes, Sir John, it is. Our First Gospel, I suspect, is Kathryn's younger brother.'

'But she never said!'

'No one ever asked her. He's no more waiting the return of St Michael and his angels than Flaxwith's dog. Come on, Sir John, let me prove it!'

The Four Gospels were gathered beneath the outstretched branches of the oak tree. There were the usual greetings and mumblings of apology.

'We had no choice,' First Gospel wailed. 'Master Whittock was most insistent.'

'Let me see one of those medals,' Athelstan demanded. 'You offered me one when I first met you.'

The fellow took one from his wallet. 'It's specially blessed …'

'Oh, shut up!' Athelstan went up and stared into the man's face. 'Do you know something, Walter Trumpington? I've yet to meet one of your kind who's got a spark of religion in him.'

First Gospel looked both hurt and puzzled.

'Are you going to act for me now? Why didn't you tell the court? Why didn't you tell me or Master Whittock that you are Kathryn Vestler's younger brother? I found an entry in the accounts book from years ago. You've tried everything, haven't you,

Walter? Chapman, tinker, mountebank, soldier? But, when times are hard, it's always back to sister Kathryn for help. She's soft-hearted, isn't she? Now, you can stand here with your three sisters and act the innocent. So I'll tell you the truth. You are a pimp, Walter, and these three ladies are whores.'

'How dare you!' one of them screeched.

'Shut up!' Sir John growled. He was as surprised as any of them but was enjoying Athelstan's fiery temper. 'If any of you make another sound,' the coroner continued, pointing across to where Flaxwith was walking up and down, Samson trotting behind him, 'I'll order my bailiff across here: he'll put you across his knee and whip your buttocks! Now, sir.' He poked First Gospel in the chest. 'Either you answer my secretarius' questions or I'll have you driven from the city!'

'Now, I don't know how you did it, how you persuaded her,' Athelstan continued, 'but Walter Trumpington decided to return to the Paradise Tree when he learned that Stephen Vestler was dead. When he was alive, the taverner kept some control over his wife's generosity to her wayward brother but, once he was gone, back you came. She's a lovely woman, isn't she, Walter?'

Athelstan paused and looked up at the tree where a blackbird had begun to sing.

'She loves you completely, doesn't she? You are the family rascal. I wager you could act the prodigal son or, in this case, the prodigal brother. In truth you are a cunning man. Anyway, Kathryn gives you a cottage on the edge of Black Meadow. You pretend to be one of our latter-day prophets. However, you are involved in quite a lucrative business: buying smuggled wine from ships, then selling it on to the likes of Kathryn, who can refuse you nothing. I wonder how much gold and silver you have hidden beneath the floor of that cottage?'

'May I sit down?' Walter's face became pleading. 'I don't feel very well, Brother.'

'Of course!'

First Gospel and his three sisters slumped to their knees. Athelstan crouched down to face them.

'In fact it was a subtle, clever ploy,' he went on. 'On one side of your cottage snakes a river where roguery thrives like weeds in rich soil. On the other side stands a deserted meadow and a prosperous tavern owned by a loving sister. No wonder you lit a fire every night – smugglers must have a beacon light to draw them in.'

'I told you about those,' First Gospel mumbled.

'Rubbish! There were no barges full of shadowy, cowled men, that was to distract us. When I and Sir Jack, coroner of the city, arrived in Black Meadow surrounded by bailiffs, you must have had the fright of your life. But that's not all you are involved in, is it, sir? The King's warships, the wool cogs and wine barges throng the Thames. Sailors are sometimes not given shore leave: so, what better for sailors, starved of female kind, than to drop the ship's bum-boat and sail up river for a tryst with one of our ladies here? And what a place to make love, particularly in summertime, along the hedges of Black Meadow? No wonder the fisher of men heard strange sounds and cries at night.'

'Do you know the sentence?' Sir John asked. 'For keeping a brothel? You can be whipped at the tail of a cart from one end of the city to the other.'

'And the gold?' Athelstan asked. 'Gundulf's treasure?'

'Oh no.' First Gospel waved his hand. 'Mistress Vestler was very firm on that: I was not to enter the tavern. Kathryn can be a strict woman. She gave me the cottage and the use of the land provided I left her and her tavern alone.'

'Is that why you did business with Master Whittock?' Athelstan asked. 'Do you have a soul? Do you have a heart? Do you realise your sister could hang? Is that why you decided to flatter the King's lawyer? To keep your place here?'

'I'm a villain!' First Gospel's face turned ugly. 'And true, Brother, I have wandered the face of the earth.' He paused. 'How did you know about the ladies?'

'Oh, something the fisher of men said. You've seen him combing the river for corpses, as well as someone else.' Athelstan smiled. 'Dead men do tell tales. Do you remember a strange character called the preacher? Tall, black hair, face burned by the sun?'

'He may have come here.'

'He took one of your cheap little medals depicting St Michael. He hired some poor whore in Southwark and got both himself and her killed. The medal was found on his corpse. However, we were talking about your sister: you gave that information to Whittock?'

First Gospel ran his tongue round his sharp, white teeth, reminding Athelstan of a hungry dog.

'He came down here.' One of the women spoke up. 'He asked if we had seen anything untoward.'

'But what you told him,' Sir John persisted, 'was not the truth.'

'No, my lord coroner, it wasn't,' First Gospel snarled, getting to his feet, standing legs apart.

He paused and looked across the field. Flaxwith had now sat down near the hedge, one arm round his beloved mastiff.

'The lawyer came down here. He asked questions. I could see he would stay until he got an answer. I told him the truth, or at least half of it. Kathryn did come down here on the morning of the twenty-sixth. She asked if I had seen anyone I knew in Black Meadow. I replied I hadn't.'

'You said it was half the truth?'

'Well, the night before, my girls were busy down behind the hedgerow. It was a balmy, soft night. I thought I would walk.' He shot a glance at Athelstan. 'I didn't tell Whittock this. I saw lantern-light, just a pinprick, so I crept up the hill.'

'And what did you see?'

'My beloved sister Kathryn. She was digging. Or rather she was finishing what she had dug. She was piling in the earth.'

'And weren't you curious?'

'Brother, I survive by keeping my nose out of other people's business. Yes, I wondered what she could be burying at the dead of night. I was tempted to search there myself.'

'You did, didn't you?' Athelstan asked. 'Don't tell lies!'

'Yes, Brother, I did, a few days later. I came across a stinking corpse so I pushed the earth back and left it alone.'

Athelstan looked at the horror-stricken coroner.

'So you see, if I wished to do my sister real damage, I could have taken the oath and told them that.'

'And you never approached your sister?'

'I've already answered that, Brother. Kathryn is kind. She showed me great charity. If I had my way I'd have dug the corpses up and slung them in the river. Anyway, I've smuggled a little wine and allowed my girls to pleasure some sailors. What are you going to do, my lord coroner, arrest me?'

'No, sir, I'm not.' Sir John turned away. 'Today is Friday. I shall return on Tuesday. And you must be gone.'

'There will be no trouble,' Athelstan added, as he undid his pouch and pulled out a piece of parchment. 'Provided you answer one question.' The friar felt a tingle of excitement as he approached the main reason for this meeting. 'When you were on oath, Master Whittock asked you about your sister's question on the morning of the twenty-sixth of June last?'

'Did I see anyone I knew here in Black Meadow?'

'Look at that list,' Athelstan said. 'You are lettered?'

'Of course, Brother.' The First Gospel grinned. 'Father always said schooling was the beginning of my downfall.'

'This is a list of names of all those who use the Paradise Tree. Which of them do you recognise?'

First Gospel studied the list carefully. Athelstan winked at Sir John. He had drawn up the names this morning in bald, round letters.

'This one,' First Gospel said, jabbing his finger.

'And, of course, this one and this one, but those two are dead.'

'Anyone else?' Athelstan asked. 'Anyone I have missed out?'

First Gospel shook his head and handed the piece of parchment back.

'Is there anything else, Brother?'

'No, sir, there isn't.' The friar turned. 'Angels might not come on time,' he declared, 'but, sometimes, God does work in wondrous ways. Master Trumpington, ladies, I will not trouble you again.'

Athelstan, followed by a bemused Sir John, walked back to the Paradise Tree.

They sat in the garden and were joined by Flaxwith. Cranston hurriedly brought the mastiff a large, cooked sausage from the kitchen. The dog seized it, grinning evilly at his benefactor.

'Just keep him away, Henry!'

A sullen tapster brought tankards of ale.

'Master Flaxwith,' Athelstan said. 'When you have finished your ale, I would be grateful if you would go for Master Ralph Hengan. You know where he lives?'

Flaxwith nodded.

'Bring him here. Tell him we'll meet him under the great oak tree in Black Meadow.' 'And if he's busy?'

'Oh, he'll come. Tell him we have found Gundulf's treasure.'

Flaxwith choked on his ale. Cranston nearly dropped his blackjack; even Samson stopped chewing the sausage.

'Brother, are you witless?'

'No, Sir John, I am not. The treasure is not very far from us. Master Flaxwith, I beg you to go.'

Flaxwith finished his ale and hurried off, Samson loping behind him.

'Where's the treasure, Brother?' Sir John whispered.

'Here in the garden.'

'Friar, don't play games. If we find the treasure, God knows we could turn Gaunt's mind to mercy'

'Oh, I'll do more than that, Sir John. Now, do you remember when we went to the Tower?' Athelstan asked. 'We do know Bartholomew read manuscripts we never saw. However, there was an entry in that chronicle about the treasure glowing like the sun. What was it now? "In ecclesia prope turrem"?'

'That's right. Which we translated as "in the chapel or church near the tower": the site of the Paradise Tree.'

'I don't think so.' Athelstan smiled. 'You see, Sir John, Gundulf was a bishop. He held the See of Rochester. I read a book at Blackfriars. His real interest wasn't theology but mathematics: he loved buildings and measurements. He was fascinated by anything which could calculate, weight or measure. Because he was William the Conqueror's favourite stone mason, Gundulf also amassed a treasure. Before his death he had it all smelted down, fashioned into one great block.'

'Yes, yes, we all know that,' Sir John interrupted.

'He was a churchman,' Athelstan continued. 'And, before he died, he used his status to hide the treasure away.'

'Where?' Sir John almost bawled. 'Why, Sir John, he had it smelted down and then covered with a brass face.'

'What?'

Athelstan pointed to the sundial. 'I think it's in there.'

Sir John stared open-mouthed at the sundial. The stone pillar which held it was covered in lichen and chipped. It reminded him of a long-stemmed chalice with the cup holding the sundial at the top. The coroner went across and tapped it with his finger.

'But it's only a sundial, Brother. Look, it has an arm.' He peered down. 'And it's divided into Roman numerals.'

Athelstan joined the coroner.

'When Gundulf talked of his treasure being in "ecclesia prope turrem"we thought he was referring to the Paradise Tree but he wasn't, Sir John. You see, since his day, the Tower has been extended and strengthened. However, when Gundulf built the great keep, that was his "turris".The church he was referring to …'

'Of course!' Sir John exclaimed. 'St Peter ad Vincula! The little chapel in the Tower grounds which stands next to the keep.'

'That,' Athelstan agreed, 'is what Gundulf was referring to. He had his treasure melted down, covered with a brass sundial and placed in the stone pillar outside the chapel of St Peter ad Vincula. The years passed. People found references to the treasure being hidden but they forgot that, in Gundulf's day, the word "tower" referred to the keep, not to the walls and fortifications we know now.'

'So how did you know it was here?'

He placed his hands around the edge of the sundial and tried to move it but couldn't.

'It was in that accounts book. Do you remember, Sir John, when we first came here? Someone told us how Stephen Vestler loved curiosities? How he'd brought shields and swords from the Tower to hang on the wall.'

'Yes!' Sir John breathed. 'And Stephen had a love of ancient things.'

'Apparently, Sir John, Stephen Vestler bought the sundial from the new Constable of the Tower. There's a reference to a cart being hired, labourers being paid for this sundial to be brought here.'

'Satan's tits!'

'And when I was in the Tower last week,' Athelstan continued, 'I could see that the small churchyard outside the Tower had been refurbished. Some of the old tombstones had disappeared. When I read that entry, I began to think.' Athelstan sighed. 'Ah well, Sir John, you are coroner, an official of the city. This tavern will soon be in the hands of the Crown.'

Sir John took his dagger out and tried to slide it between the rim dividing the sundial from the grey-stone which held it.

'I doubt if you can move it,' Athelstan said.

The coroner went back to the Paradise Tree and returned carrying a heavy hammer. The ale-master came out protesting.

'Oh, shut up!' Sir John bellowed. 'And stand well

He threw his cloak over his shoulder and began to smash the stone cup which held the sundial. At first all he raised were small chips of flying stone. Time and again he brought the hammer down. The stone split, crashed and rolled on to the grass. Even before the dust cleared Athelstan knew he was correct. The stone cup had broken; on the grass, covered in a grey film of dirt, was a circle of glowing yellow about a foot across and at least nine inches thick. It lay like the cup of a chalice without the stem, beside the thin bronze face of the old sundial. Sir John and Athelstan crouched down, the rest of the servants clustered round. Athelstan took the hem of his robe and rubbed the yellow metal until it glowed, catching the rays of the sun.

'Fulgens sicut sol!'Athelstan said. 'Glowing like the sun and hidden under the sun!'

The gold, because of the way if tapered at the end, tipped and turned. Everyone's face, including Sir John's, had a strange look, eyes fixed, mouths open.

'I've never seen so much!' the coroner said wistfully. 'Not even the booty of war piled high on a cart.'

'As the preacher says,' Athelstan remarked, 'the love of wealth is the root of all evil. This was Gundulf's secret as well as his little joke. He was dying, probably a sickly man, and he thought he'd used his treasure for something useful. So he left the riddle for those who wished to search for it. Time passed and people made mistakes.' Athelstan tapped the gold with his finger. 'This has been the cause of all our troubles. Sir John, you'd best tell people here to keep a still tongue.'

Sir John got to his feet and drew his sword.

'This is the King's treasure!' he bellowed. 'To take it, to even think of stealing it, is high treason!' He pointed to the ale-master. 'You, sir, bring a barrow!'

The man didn't move, his eyes still on the gold. Sir

John lifted his sword and pricked him under the chin.

'Bring a barrow and a piece of cloth. Brother, we are going to need a company of archers to take this to the Tower.'

'We are not taking it there, Sir John, but into Black Meadow,' Athelstan said quietly. 'Go on, man!' he ordered the ale-master. 'Do what the coroner says!'

The fellow hurried away. A short while later he returned trundling a wheelbarrow, a dirty canvas sheet folded inside it. They tried to lift the gold in but it was too difficult and slippery so the handcart was laid on its side, the gold was eased in and covered with the sheet. With the help of the ale-master Sir John trundled it out of the garden and down under the shade of the great oak tree.