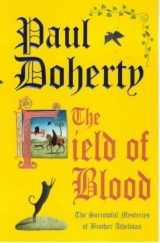

Текст книги "Field of Blood"

Автор книги: Paul Harding

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 13 страниц)

'I think you know already,' Sir John said quietly. 'The accounts for the Paradise Tree. It's a very prosperous tavern. Perhaps too prosperous.'

Hengan put his face in his hands.

'I've asked my bailiff Master Flaxwith to seize the accounts books and take them to an old acquaintance of mine.'

Hengan lowered his hands.

'Kathryn is a shrewd businesswoman,' he replied. 'The Paradise Tree is very popular: clean, fragrant, well-swept while the food its kitchen serves is delicious. But, yes, Sir John, on a number of occasions I have questioned Kathryn about the large profits she makes.'

'And what did she say?'

'At the time she laughed.'

'She won't laugh now,' Sir John observed. 'All of London will be agog with this. Did Mistress Vestler make a profit out of the customers she killed? Or has she already found Gundulf's treasure? The tavern owns a forge; gold can be smelted down. By the time Sir Henry Brabazon has finished with her, she'll not only be accused of murder and robbery but stealing treasure trove from the Crown and that's petty treason. A fine mess, master lawyer. Indeed, the more I find out about my old friend the less I like it.'

'You can't desert her!' Hengan pleaded.

'For the sake of Stephen I won't! But I think we are finished here. Master Flaxwith will be waiting.'

'And afterwards?' Hengan asked.

'I'm hungry and thirsty. I'm going to visit the Lamb of God in Cheapside. You, master lawyer, Brother Athelstan, are welcome to join me. We'll take physical and spiritual comfort before we visit our friends in Newgate.'

Athelstan hurriedly took the manuscripts he had found and put them into his chancery bag, which now weighed heavy with the book the Venerable Veronica had given him. They went out on to the Tower green, thanked Colebrooke and walked down the narrow cobbled path which wound between the walls towards the Lion Gate.

The entrance to the Tower was busy with carts and sumpter ponies being taken in and out. Members of the garrison on patrol along the quayside were now returning. Chapmen, tinkers and traders had opened their booths to do a brisk trade. Cranston climbed on to a stone plinth and looked over the sea of heads and faces.

'Flaxwith!' he bellowed. 'Henry Flaxwith!'

Athelstan's attention was caught by a small crowd which had gathered round a Salamander King: one of those fire-eaters who went round the city performing their tricks. The man was assisted by a small boy who held the reins of a sumpter pony. A small booth had been set up for tankards of ale and the fire-eater was drawing onlookers to him. He was dressed in a mock scale armour with a red lion on the breast, brown leggings and thick leather boots. On his head he wore a tawdry coronet over a rather shabby wig with bright bracelets on each wrist. He'd lit a rush light and, as the crowd uttered gasps of wonder, lifted this and put it in his mouth chewing as one would a morsel of food. When he withdrew the rush light, the flame had gone. As the crowd clapped, he extended his clap-dish for contributions. Athelstan, intrigued, walked over. The Salamander King had suffered no ill-effect: his sunburned face broke into a smile as he glimpsed the friar.

'A miracle eh, Brother?'

'Everything's a miracle.' Athelstan grinned back. He offered the Salamander King a penny. 'I must hire you for St Erconwald's in Southwark, the children would love it.'

'I am always about the city, Brother. Just ask for the Salamander King.'

Athelstan thanked him. He was about to turn away when he noticed something glinting against the pony's neck. 'Excuse me.'

He walked over and grasped the St Christopher medal hanging down from the saddle horn, which was almost identical to the one Bridget Sholter had shown him. It had the same thickness, but the chain was not so bright and the locket itself was dented and splattered with mud.

'What's the matter, Brother?' The Salamander King drew closer.

'I am intrigued, sir. This is a St Christopher medal. You don't wear it because it interferes with your tricks?'

'Of course not, Brother. This is a St Christopher locket, but you don't wear it round your neck. Here, I'll show you.'

He took the chain off the saddle horn and looped it over Athelstan's head. The locket itself lay against his stomach. The chain, being so thick, was rather heavy. He could certainly feel its weight.

The Salamander King took it off and put it back over his saddle. 'The locket is supposed to hang down so, as you get on and off your horse, you see it.' He picked up the medal and kissed it. 'That's what I do during my journey. I also touch it whenever I have to cross a rickety-looking bridge or ford a river.'

Athelstan closed his eyes. 'I should have known that,' he murmured. 'Oh friar, as Sir John would say, your wits are fuddled.'

'Are you all right, Brother?'

Athelstan opened his eyes and slipped another coin into the Salamander King's hands.

'God works in wondrous ways, sir,' he said. 'Angels do come in many forms.'

And, leaving the bemused fire-eater, Athelstan returned to where Sir John had at last traced his chief bailiff.

Chapter 9

Sir John wouldn't listen to what Flaxwith had to say but marched from the Tower as if he were leading a triumphant procession. He strode ahead up Eastchepe, Gracechurch Street, Lombard Street and into the Poultry. When they reached Cheapside it was thronged with crowds flocking round the stalls and markets. The pillories were full of miscreants trapped by their necks, fingers, arms or legs. Others had been herded into the great cage perched on top of the conduit which distributed water to the city. Sir John waved at all his 'lovelies' as he passed: night-walkers, rifflers, roaring-boys, pickpockets and drunks. He was met with sullen stares or abusive ribaldry.

The coroner was well known in the area, and his towering figure and luxuriant moustache and beard only highlighted his rubicund face. Ladies of the night, 'my little Magdalenas' as Sir John described them, disappeared at his approach up dark alleyways and runnels. He stopped to throw a penny at a whistling man who could imitate the call of the birds and roared at the cheap Johns, their trays slung around their necks, to keep their distance. Flaxwith and two other bailiffs, plodding behind Athelstan, quietly laughed at some of the names Sir John was called. Abruptly the coroner stopped as if transfixed, blue eyes protuberant, mouth gaping. 'Oh Satan's tits!' he breathed.

Athelstan stood on tiptoe and saw heading for Sir John, Leif the one-legged beggarman.

'That bugger can move quicker than a grasshopper!'

Leif, together with his constant friend and companion, Raw Bum, always had an eye for Sir John. For some strange reason Lady Maude was much taken by this beggar who pleaded for alms and food outside kitchen doors and entertained the whole of Cheapside with his new found role as chanteur or carol-singer. Athelstan suspected that Lady Maude used Leif as a spy on Sir John's whereabouts, particularly his visits, fairly regular, to the Lamb of God.

'Ah, Sir John.'

Leif rested on the shoulder of Raw Bum, a rogue who'd suffered the misfortune of sitting down on a scalding pan of oil.

'Good morrow, Leif.' Sir John was already fishing into his purse for two pennies.

'The Lady Maude is well. She was much taken by my new carol: "I am a robin" …!'

'You will be a dead robin if you don't get out of my way!' Sir John growled.

'The Lady Maude is in good fettle,' Leif prattled on. 'But your two hounds Gog and Magog were in your carp pond and the two poppets …'

'What's wrong with the lovely lads?'

'Oh nothing, Sir John, they are just soaked and wet.'

'And?'

'The Lady Maude asked me to keep an eye open to see if you returned to Cheapside …' He took the pennies offered. 'But, of course, Sir John, I haven't seen you.'

And Leif, helped by Raw Bum, hobbled away.

Sir John, muttering curses under his breath, swept into the taproom of the Lamb of God. The taverner's wife bustled up. Sir John was taken to his favourite seat by the window where he ordered tankards for Athelstan, Hengan, Flaxwith and his two bailiffs. Once these had been served, the coroner leaned back in his seat.

'Well, Flaxwith?'

'I've been across to the Merry Pig, sir.'

'A well-known brothel house. Go on.'

'Alice Brokestreet entered the service of the Merry Pig weeks ago. Not as a whore, though she may have granted her favours, but more as a chamber girl and wine maid. She killed a clerk in a quarrel and escaped but the hue and cry were raised.'

'And?' Sir John asked testily. 'The vicar of hell?'

'The tavern-keeper said he had no knowledge of such a man.'

'I am sure he did.'

'But, he said that if he came across him, he would present the compliments of my lord coroner and Brother Athelstan.'

'Do you hear that, friar?'

Athelstan, lost in a reverie, started and looked at Sir John.

'A brothel-keeper knows you.'

'We are all God's children, Sir John.'

'What are you thinking about, Brother?'

Athelstan picked up his writing bag, took out a scrap of parchment, seal, inkpot and quill. He wrote a few lines.

'I'm thinking about St Christopher medals, Sir John.'

Athelstan shook the piece of parchment to ensure the ink was dry. He took a penny out of his purse and handed the coin and scrap of parchment to Flaxwith.

'When you've finished your ale, Henry, would you and your lads go back to Petty Wales. Seek out a young woman called Hilda Smallwode in Shoe Lane: she's maid to Bridget Sholter.'

'Oh, the widow of the murdered messenger?'

'Ask her the question I've written out. Did she see her master's medal hanging from his saddle horn or did she notice it in the house after he had left? You are to tell her you are from Sir John Cranston and she's to keep the matter secret.'

Flaxwith, eager to be away, drained his tankard and got to his feet, gesturing at his companions to follow.

'By the way,' Athelstan asked, 'where's Samson?'

'I've left him at a horse leech in Bodkin Lane.'

'Ah!' Sir John breathed. 'Don't say the darling boy's ill?'

'Something he ate, Sir John. He stole a string of sausages from a butcher's stall last night and the little fellow hasn't been the same since.'

Sir John raised his tankard and toasted him.

'Do give Samson my love.'

Flaxwith stamped out, complaining under his breath about Sir John's attitude to his beloved dog. The coroner ordered more tankards.

'I've got some bad news. While you were away looking at that fire-eater, Athelstan, I asked Henry about the accounts of the Paradise Tree but they've already been taken. Odo Whittock has, in the name of the chief justice, seized them already' Sir John dug into the deep pocket in his cloak and drew out a tattered ledger. 'That's all he could find but it's five years old, the last year Stephen Vestler was alive. I was going to …'

'I'll have it, Sir John.'

Athelstan took the greasy-covered ledger, bound by pieces of red twine, and put it in his writing bag. Hengan was staring down at the table lost in his own thoughts.

'Master Ralph, you look sad.'

'Brother, I am more frightened.' Hengan sipped at the fresh tankard of ale. 'It does not augur well for Mistress Vestler. We know that the two corpses are those of Bartholomew the clerk and his sweetheart but there's also the question of the other skeletons.' He paused. 'Is it possible?'

'What?' Sir John demanded.

'Well, all the flesh and cloth had rotted away. Now around the city are numerous burial pits, relics of the great pestilence which swept through London thirty years ago. People were buried in gardens, any available piece of land.'

'And you think that's what happened in Black Meadow?' Athelstan asked.

'It's a possibility. I mean, if Mistress Vestler was a murderess, wouldn't we find or discover more corpses in the same state as Bartholomew?'

'There's one place I can look,' Athelstan added, 'my mother house in Blackfriars. When the pestilence swept through London the Dominican order did very good work. The brothers tended to the dead but they also made a careful list of burial grounds and, when the pestilence subsided, went out and blessed these.'

Sir John beamed from ear to ear.

'It's possible,' he whispered excitedly.

'But it makes little difference,' Hengan intervened. 'What does it matter if you hang for one or a dozen? Sir John, I think we should be going.'

They left the Lamb of God and made their way up through the milling crowds and into the open area before the grim doorway of Newgate. To one side ranged the fleshers' stalls and slaughterhouses. The cobbles ran with blood and ordure and the air was thick with the stench from the boiling cauldrons and vats.

Athelstan always hated the place. It stank of death, pain and punishment. The stocks in front of the prison were empty but a makeshift scaffold had been assembled. It was rarely used as an execution place but as a stark warning to the riff-raff who thronged about. In front of the massive gate swarmed beggars, grubby-faced clerks and scriveners eager to write messages for the unlettered. Turnkeys and gaolers moved about accepting bribes and gifts so people could be allowed through the metal-studded postern door into the yard beyond. Two prisoners had been released to beg for alms for those housed in the common cells. They wore nothing but loin cloths.

They were shackled together by long chains round their ankles and wrists, their emaciated, sore-covered bodies a pathetic reminder of the terrible conditions within. One of these pushed his clap-dish beneath Athelstan's chin.

'Some coins, Brother? Something for the poor within?'

Athelstan dropped a penny in but a sweaty-faced beadle was following the two prisoners so Athelstan wondered if the alms would go to those who needed them or the corrupt officials who regarded Newgate as their private fief. He followed Sir John up to the gate. The coroner had little time for the turnkeys. He simply showed his seal and thrust by them into the common yard. A gaoler took them across and up into the inner gatehouse.

Chambers stood on each floor. Athelstan glanced through an open door and recoiled in disgust: he was sure that a tray, lying within the doorway, held the severed ears of malefactors.

'Sir Jack,' he protested, 'I hate this place!'

They reached the fourth floor and the gaoler stopped before a heavy door set into the recess. When he unlocked the door Athelstan expected to see Mistress Brokestreet but it was flung open by a tall, black-haired man, thin-faced with a receding chin and a sharp-beaked nose which scythed the air. He was dressed from head to toe in a velvet gown of dark murrey trimmed with fur. The gaoler stepped hastily aside, almost knocking into Sir John in the narrow stairwell.

'Who are these people?' The man came out, closing the door behind him.

'Sir John Cranston, coroner of the city, and you, sir?'

'Master Odo Whittock, serjeant-at-law. Special emissary of Sir Henry Brabazon the chief justice.'

He looked over Sir John's shoulder, espied Hengan and his narrow eyes twinkled in amusement.

'I wager you've come to see Mistress Brokestreet. But the answer is no. Mistress Brokestreet is now a prisoner of the Crown and whatever you want to know can be learned in court.' He gestured with his finger. 'Above us lies Mistress Kathryn Vestler. I will not question her.' His lips parted in a smile. 'At least not now.'

And, without further ado, Whittock went back in, slamming the door behind him. The gaoler turned, his unshaven face creased into a smile.

'Sir John, I…'

'Oh bugger him!' Sir John growled. 'Let's see Mistress Vestler.'

The cell they were shown into was clean-swept, the shutters on the barred windows wide open; Mistress Vestler must have paid considerable amounts for a cell such as this. It contained a pallet bed, a bench, a table and two stools as well as a leather coffer with broken straps and buckles pushed against the wall. Clothes and blankets hung from pegs on the wall; on the table was an unfinished meal of bread, dried meat and some rather bruised apples. Mistress Vestler was staring out of the window and turned as they came in. If anything, Athelstan thought, she looked younger, more resolute than before. Her face was now hard set, no trace of any tears. She went and sat on the bed and watched as they came over. The gaoler locked the door behind them. She smiled up at Hengan.

'Have you come to take me home, Ralph?'

The lawyer coughed and shuffled his feet.

'Mistress, Sir John and I have questions for you.' She sighed, more concerned with straightening the dark-blue veil which covered her greying hair.

'I'm well looked after here,' she said. 'The place is clean. The gaoler says it's too high for the vermin.' She glanced at Athelstan who brought a stool across. 'It's good of you to come, Brother. I understand you have troubles of your own. A royal messenger killed in your parish?' She shook her head. 'It's so sad. I knew both Eccleshall and Sholter. Oh yes.' She saw the surprise in Athelstan's face. 'They often travelled from Westminster to the Tower and came striding into the Paradise Tree shouting for custom.'

'What were they like?' Athelstan asked as Sir John and Hengan brought across a bench.

'Oh, bully-boys both, especially Sholter; he would always swagger in roaring for a drink. Now he's gone! Life is truly a valley of shadows isn't it, Brother? But you have questions?' She didn't look at Sir John but at Athelstan. 'I also know your reputation: small and gentle with eyes which never miss anything.'

Athelstan smiled at the compliment. 'Mistress Kathryn, we are here to save you. I will be honest, that is going to be very hard.'

Mistress Vestler blinked, her lower lip quivered but she maintained her composure.

'Did you kill Bartholomew Menster and Margot Haden?'

'I did not.'

'Do you know how their corpses came to be buried in Black Meadow?' 'I do not.'

'Can you, Mistress Vestler,' Athelstan persisted, aware of how quiet this cell had fallen, 'remember the twenty-fifth June, the day after midsummer? That was the last day Bartholomew and Margot were seen alive.'

'I don't know, I can't remember.'

'What do you think happened?'

'Bartholomew must have come into the tavern to eat, drink and meet Margot.' She shook her head. 'But, apart from that …'

'Why did you burn Margot Haden's property?'

'I've told you that, it was tawdry, only cheap items. I thought she had eloped and wouldn't need them any more.'

Athelstan's heart sank: just a flicker of the eye but he was sure she was lying.

'Did Bartholomew Menster ever offer to marry you?'

'Of course not!'

'Were you jealous of his affection for Margot?'

She shook her head, and Athelstan sensed she was telling the truth.

'Did Bartholomew Menster ever discuss with you the legends of Bishop Gundulf's treasure, about it being like the sun?' He paused. 'And hidden beneath the sun.'

Athelstan abruptly recalled that no reference to the latter half of this cryptic riddle had been found in the manuscripts he had taken from the Tower.

Kathryn was now agitated, rubbing her hands together.

'The Tower is full of such legends,' she replied. 'Hidden gems, lost jewels, Gundulf's treasure hoard, Roman silver.'

'Did you and your late husband Stephen know about these lost treasures of the Tower?'

'Of course. We lived within bowshot of the Tower. Stephen was always buying artefacts from the garrison: shields, disused weapons and other curiosities. You've seen most of them yourself! True, Bartholomew discussed the legends with me but I just laughed.'

'Did he ever offer to buy the Paradise Tree?' Sir John broke in.

Kathryn was about to deny that.

'He did, didn't he?' Athelstan persisted.

'On two occasions,' she replied slowly, 'he made an offer but I refused.'

'And you never thought it strange,' Athelstan asked, 'that a clerk, a scribe from the Tower, was interested in the tavern? Didn't you think his interest in the treasure was, perhaps, more than a passing mood?'

'He made offers. I refused and that's the end of the matter.'

'Well, perhaps we have some good news,' Athelstan said. 'The other skeletons were probably victims of the plague: Black Meadow may have been a burial pit when the great pestilence raged.'

Kathryn smiled. 'It's possible. Perhaps that's why it was called Black Meadow.' She wiped her mouth on the back of her hand. 'Stephen always talked about ghosts being seen there.'

'More than ghosts, mistress. The Four Gospels, that strange little company whom you so generously allowed to stay in Black Meadow, have reported barges coming in on the mud flats. Of dark shapes and shadows entering Black Meadow in the direction of the Paradise Tree.'

'I know nothing of that,' she retorted sharply. 'The Thames is like any highway, both good and bad travel there.'

'But where do they go to?' Athelstan asked.

'Petty Wales is a den of thieves.'

Athelstan fought to control his temper.

'Mistress Vestler, in this gatehouse is a serjeant-at-law, Master Odo Whittock. He and Sir Henry Brabazon are, to use Sir John's term, "two cheeks of the same face". They will dig and dig deeply. They will not be satisfied by your answers in court.'

'It's the only response they will get, Brother.'

'Mistress Vestler, I am trying to help. I have been to the Paradise Tree and it's a fine, prosperous tavern. Questions will be asked about your profits.'

'I am a good businesswoman,' she insisted. 'Brother, if I could have a cup of water?'

Athelstan rose, filled a cracked pewter cup and passed it over.

'My profits are what they are.' She sipped at the water. 'I can say no more.'

Athelstan saw his despair mirrored in Sir John's eyes.

'In which case, Mistress Vestler, I will pray for you and do what I can.'

'I will stay,' Hengan said. 'I need to talk about further matters.'

Sir John went across and hammered on the door.

The turnkey waiting on the other side opened it. They went down the steps and out into the cobbled yard. Athelstan plucked at the coroner's sleeve.

'It does not look well, Sir John.'

'No, Brother, it doesn't.' He paused at a scream which came from a darkened doorway. 'Hell's kitchen! That's what this place is: let's be gone!'

Outside the main gate, Henry Flaxwith stood holding a slavering, smiling Samson in his arms.

'You see, Sir Jack, he's well enough now.'

The dog lunged at Sir John, teeth bared.

'Samson is so pleased to see you, Sir John. You know he loves you.'

'Master Flaxwith, I'll take your word for it. Now, put the bloody thing down!'

Flaxwith lowered Samson gently down on to the cobbles and the ugly mastiff pounced on a scrap of meat from the fleshers' yard.

'And my errand?' Athelstan asked. 'To Hilda Smallwode?'

Flaxwith pulled a face. 'I am not too sure whether you will like this. The maid, who is honest enough, said she did not see Master Sholter actually leave, she was in the house. Her mistress stayed for a while but she did send Hilda upstairs to the bedchamber. The maid remembers seeing the St Christopher on a stool but didn't think anything of it. She certainly saw it again on Sunday morning when she called round to see if her mistress was well.'

Athelstan closed his eyes and quietly cursed.

'Well, well, Brother.' Sir John patted him on the shoulder. 'It would seem your theory will not hold up. Master Sholter did forget his St Christopher.'

Athelstan just rubbed the side of his face. 'Sir John, I must think while you must see your poppets.'

And, hitching his chancery bag over his shoulder, Athelstan despondently walked away, leaving a bemused coroner behind him.

Athelstan trudged on, oblivious to the crowds around him, to the constant shouts of the apprentices: 'What do you lack? What do you lack?' Tradesmen plucking at his sleeve, trying to attract his attention; whores flouncing out of doorways. All the little friar could think of was Mistress Vestler sitting there, telling lies while, across the city, two assassins hugged themselves in glee at the terrible crimes they had committed.

Athelstan paused, breathed in and coughed; the friar was suddenly aware that he had gone through the old city gates. He was now near the great Fleet Ditch which stank to high heaven of the saltpetre which covered the mounds of rubbish. Two urchins ran up, saying they would sing him a song for a penny. Athelstan tossed them a coin and sketched a blessing in the air.

'I'll give you that for silence,' he told them. 'Blackfriars!' he announced. 'I'll go to Blackfriars!'

'And then to heaven?' a chapman who had overheard him called out.

Athelstan smiled and walked on, lost in his thoughts and what he had learned.

At last he arrived at the mother house. A lay brother let him through the postern door. Athelstan seized him by the shoulders and stared into the man's vacant eyes, the saliva drooling from slack jaws.

'It's Brother Eustace, isn't it?'

'Abbot Eustace to you,' the lay brother replied.

Athelstan squeezed the old man's shoulder.

'And I am the Cardinal Bishop of Ostia,' he hissed. 'I've come to make a secret visitation, so don't tell anyone I'm here.'

The lay brother chortled with glee. Athelstan moved on across the cloister garth and into the heavy oak scriptorium and library. The old librarian was not there. Athelstan quietly thanked God, otherwise it would have been at least an hour of gossip and chatter. The assistant, a young friar who introduced himself as Brother Sylvester, welcomed him with the kiss of peace.

'I've heard of you, Brother Athelstan. They say when you were a novice you ran away to war.' The words came out in a rush. 'And your brother was killed and you came back and so they made you parish priest in Southwark.'

'Everyone knows my story.' Athelstan grinned. 'But, Brother, I am in a hurry. Is it possible to have a history of the Tower and the Book of the Dead?'

'I know the former,' Brother Sylvester replied. 'But the other?'

'It was written about twenty years ago,' Athelstan explained. 'It lists all the burial pits left from the pestilence.'

'I'll have a look.'

Athelstan sat down at one of the tables. The chair was cushioned and comfortable. He noted the oaken book shelves, the lectern with its precious calfskin tomes chained to the stand; racks of parchments and vellum. Books on scripture, theology, history and science. Athelstan closed his eyes. It brought back memories of his novitiate, the smell of polish mingled with that of beeswax, dried leather and fresh parchment.

'Brother Athelstan?'

The assistant librarian had two tomes in his hand. He put these down in front then opened the window behind to provide more light. Athelstan begged a scrap of parchment and a quill before opening the tome with the title Liber Mortuorumengraved on the front. The pages were thin, yellowing with age, but the clerkly hand was still distinct. It listed the graveyards of London, even at St Erconwald's. Athelstan scanned this entry quickly: two or three pages full of those buried there. He quietly promised himself that, one day, he would return and study it more closely. At the back the entries became more haphazard but, at last, he found the place: Ager niger Prope Turrem,Black Meadow near the Tower. 'In hoc loco,'the entry began, 'In this place, many were buried in the autumn of the year of Our Lord 1349. The field was blessed and consecrated by Brother Reyward who tended to those,' here Athelstan had difficulty with the doggerel Latin, 'who had fallen sick and been placed in the tavern near the river, now used,' and Athelstan noticed the word 'hospicium'.

'So, it was a hospital,' Athelstan murmured.

He took down the title of a book and the entry on a scrap of parchment.

'Have you found what you wanted, Brother?'

Athelstan smiled. 'Yes thank you.'

He should have felt elated but he was tired and hungry. Certainly the entry proved that at least

Mistress Vestler had not murdered indiscriminately. He sighed and opened the other book, A History of the Tower and its Environsby a chronicler who had lived fifty years earlier. It was not really a history but more a general description and chronicle of outstanding events, such as the legend that Julius Caesar built the Tower. Crudely drawn maps described the different buildings: the curtain wall, towers and chapel but nothing significant. Athelstan closed the book, thanked Brother Sylvester and left.

Once he was through the postern gate, Athelstan regretted not visiting the refectory or kitchen. Instead, he went into a tavern, the Mailed Gauntlet, a stone-built alehouse with a small rose garden beyond. The kindly tavern-keeper took him out to a turf seat and served him a pot of ale and a freshly baked meat pie. Athelstan sat and basked in the late afternoon sun. He would have liked to visit Sir John but what would he say? He should really be helping the coroner but, in truth, he felt a terrible anger against those two assassins playing 'lovers' cradle' in Mincham Lane.

'How did they do it?' he asked himself.

He thought of Sholter and Eccleshall riding across the bridge and, later that evening, a rider hurrying back.

'Of course!' Athelstan exclaimed. 'A horse is easy to get rid of but what about a saddle?'

Chapter 10

Athelstan left the alehouse determined to visit the Barque of St Peter, the rather eccentric name that eerie figure, the fisher of men, gave to his chapel or deathhouse. It was late afternoon and the crowds still thronged, particularly around the food stalls; they eagerly bought produce, reduced in price, before the market horn sounded for the end of the day's trading.

Athelstan, refreshed, made his way quickly along the streets. Above and around him three-storied houses, pinched and narrow, blocked out the sunlight, forcing people to knock and push each other in the busy lanes below. The friar threaded his way past the booths piled high with brightly coloured linen from Brussels, broad cloths from the West Country, drapes and wall sheets from Louvain and Dordrecht. Athelstan then entered Trinity where the traders sold more exotic goods, brought by the low-slung Venetian galleys now docked in the Thames: chests of spices; bags of saffron; gingers and aniseed; casks full of dried figs; oranges and lemons from the islands of Spain; crates full of almonds and mace; sacks of ground sugar, pepper and salt.