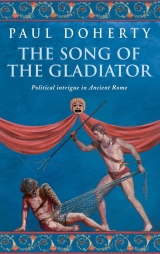

Текст книги "The Song of the Gladiator"

Автор книги: Paul Doherty

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

Septimus would never forget that bone-jarring ride through the freezing night. They had been given no respite, their pleas and cries ignored, hoods pulled over their heads. He and Dionysius had only recognised each other by their voices; they did not know any of the other prisoners. They had been bundled out of the cart in a chilling dawn, the smoke and flame from the torches of their escort pluming about them, then pushed down yawning, hideous tunnels. Only then did Septimus realise, in his fear-crazed state, that they were within the bowels of the great Flavian amphitheatre, possible victims for the games.

Septimus knew all about heaven, the place of the Christ Lord, but the priest who had converted him had also described the torments of Hell. On that terrifying morning Septimus half believed he had died and was being exposed to the terrors of eternal darkness. They had been kept in a cavern which reeked of wild animals, the roars and snarls of which echoed threateningly through the darkness. The hours seemed to drag; they were given no food or drink. Septimus, overcome with exhaustion, had fallen asleep, only to be woken by the crowds roaring like the thunder of an angry sea. Black-masked guards had appeared, their hoods were removed and they were hurried along the filthy tunnels to the gaping Gate of Death, which stretched out to the great amphitheatre, ablaze with sunlight.

Septimus could only stand and watch as the horrors of the day unfolded. Men, women and children were pushed out to be hunted by wild beasts, brought down by panther, lion and tiger or gored and tossed by furiously stamping wide-horned bulls. He had watched other human beings being torn to pieces so that the golden sand of the arena became as bloody and messy as a butcher’s stall. Yet this was only to whet the appetite of the mob. Septimus had been thrust aside as other victims, dressed in cloaks of tar and pitch and fastened to poles on moving platforms, had been pushed into the arena and lit by bowmen with flaming arrows, turning the victims into screaming, living torches.

Eventually Septimus fainted, only to be kicked awake, a coarse wine-skin bag pushed between his lips. He thought his turn had come and, looking around, glimpsed Dionysius, so overcome with fear he had lost all control over his bowels and bladder. Nevertheless, as the dreadful day continued, neither he nor his companion was thrust out with the rest. Instead, when the games were over, they had been taken back to a cell deep beneath the amphitheatre and visited by shadowy-faced men. They had made him an offer: life and freedom, protection against the macabre sights he had seen, on one condition. He must tell them everything he knew about the Christian community at Capua, then continue to give information, leaving it at certain specified places around the town when instructed. Septimus had agreed. He had fallen to his knees and begged for his life. His captors had dealt him a good beating, to convince the others back at Capua that he had not been treated tenderly. He had also been given a good meal, a purse of coins and released with letters of protection.

Once he had returned to Capua, Septimus explained how he had withstood the torture, refused to break and was released for lack of evidence. He was regarded as a hero, fêted and honoured, being given a prominent place in the Christian assembly. A week later Dionysius returned with a similar story. The two men hardly ever spoke, avoided each other’s company and never again referred to what had happened in those dark caves beneath the earth. The persecution had raged. Septimus had done his share of betrayal until the civil war had broken out. The authorities were no longer concerned about Christians but who was to rule in Rome. By then, Septimus had won a reputation as an orator and scholar, whilst Dionysius had espoused the teaching of Arius. Septimus liked that. It gave a name to their enmity, it separated them; until Dionysius had opened secret negotiations with the orthodox party and Septimus had begun to wonder how much he knew.

Septimus felt his belly grip with fear. He started in pain at the cramp in his left leg. He pulled himself up and became aware of the cries and shouts, the patter of running feet from outside. He hastily put on his sandals, grabbed a cloak, and ran out into the passageway. Servants were hurrying along. One was carrying a bucket of water. From deeper in the palace echoed the clash of cymbals and shouts of ‘Fire!’ Septimus decided to find out what was happening, but he and the rest were stopped by guards in the corridor leading to the imperial apartments. An officer brusquely informed him how a fire had broken out in one of the chambers but that no one had been hurt and the blaze had been quickly controlled.

Septimus walked away. He returned to his own room and found a scrawled note pushed under the door. He rubbed it between his fingers, screwed the piece of parchment up and thrust it into his wallet. He then left his chamber and, walking as nonchalantly as he could, went through the palace and out to the latrines. He opened the door and went in. They were empty.

‘Are you here?’ Septimus called.

A shadow moved from his right. Septimus didn’t turn quickly enough to escape the stunning blow to his head, which sent him crashing to the ground in a heap. He was half unconscious, aware of being dragged across the tiled floor. He tried to move his hands but they were already bound. The terrors of what had happened before, his nightmares from years past returned to haunt him. A door opened and Septimus was dragged down into the darkness. He felt his belt and wallet removed. He was aware of a mustiness, a cloying warmth, the smell of stagnant water. He tried to groan and became conscious of the gag pushed into his mouth. Dionysius! Was the same thing happening to him?

Pains shot through his head, his body was sweat-soaked, the harsh breathing of his captor echoed ominously. Septimus was thrust against a pillar, ropes tied around him. He had lost his robe and now his tunic was ripped apart. Behind him he could hear shuffling feet, and someone gasping for breath, as if they had run fast over a long distance. A whip cracked, and Septimus screamed silently as the first lash cut across his exposed back.

Chapter 7

‘ Cui bono? ’ (‘Who profits?’)

Cicero, Pro Milone, XII

The galley which usually patrolled the Straits of Byzantium as the Glory of Corinth had been painted black. Its red-gold taff-rail had been covered over, as had the gold-embossed griffin’s head on the stern, and the eagle with spread wings and the Horus Eye on the jutting prow. Its reefed sails were black, whilst its crew had been trained to row with muffled oars. The galley had slipped from the main battle fleet exploiting the late summer weather to leave the Aegean and enter the Middle Sea. It had stood off Sicily, then moved along the Italian shoreline, making careful use of deserted coves and inlets. If danger threatened, false flags and standards were raised. To the curious, it was just another war galley patrolling the coast against pirates. Well supplied with water and stores, the galley had taken up its agreed position on the appointed day and waited for the signal. At last it had come, a series of beacon lights clearly seen from the sea. The captain of the galley had moved his craft in, lean and low in the water like some sinister wolf slinking towards a sheep pen. The sea was calm and the pilot knew all about the currents and hidden dangers, so they successfully beached the galley at dusk.

The soldiers and marines, dressed in breeches and tunics under coats of mail, now prepared to move inland. They had all been selected for their loyalty and training. They were veterans, skilled in the ambushing and killing of bandits and outlaws in the Taurus Mountains near the Cilician Gates. They were armed with bows, arrows and long curved swords, with roundel shields slung over their backs, on their heads reinforced leather helmets with nose guards and earflaps. Some carried makeshift ladders, long poles with rods either side, as well as grappling irons, tubs of pitch and small pots of fire. They ate their meal of hard bread, dried fruits and salted meat and took a gulp from the small water bottle each man carried before moving forward.

Once they’d reached the sand hills they paused for a while to finish their preparations and sent their skirmishers forward into the trees. These scouts, Vandal mercenaries, silenced all life in the lonely farmsteads and cottages, cutting the throats of all they met, butchering the dogs and helping themselves to any plunder. The officers had studied their maps of the area most closely. The countryside around the Villa Pulchra was fairly deserted, the result of successive imperial decrees. This helped them, as did the information they’d received about the villa’s security. It was under the command of Gaius Tullius, a veteran officer of Constantine who shared his command with Burrus, commander of the great bitch Helena’s guard. The attackers had been given strict instructions. Constantine and his mother were to be assassinated, the likes of Burrus, Rufinus, Chrysis and Gaius Tullius taken prisoner, along with the priest Sylvester and the leader of the orthodox party, Athanasius. Everyone else was to be put to the sword.

The attacking force moved deeper into the woods. Climbing the slopes, they reached a glade, where they regrouped and rested, sharing out the paltry spoils of their plunder. They drank some more water and moved on. After a great deal of trekking they reached the approaches to the villa. Occasionally they would come across guards on picket duty, but these were few and sleepy-eyed, and soon disposed of. The undergrowth outside the villa was thick, so they were forced to use the only track. The captain in charge had no choice in the matter, yet he guessed something was wrong. He could feel it in the prickling of the sweat along his back. Was it the silence of the woods? The absence of any owl hoot or flurry amongst the undergrowth? Had the animals also sensed something threatening and fled? Now and again the captain would pause, listening for the sounds of the night. He looked back. All he could see in the faint moonlight was a bobbing line of men. Despite his suspicions, he was totally unaware of the dark, hulking shadows following his men either side of the path. These shapes, used to the pitch darkness of the German forests, slipped like hunting wolves through the bracken, grouping round the end of the column. As the line of attackers moved more quickly, stragglers began to appear, and the silent shadows took these, a hand about the mouth, a knife across the throat. .

Claudia gazed round the opulent triclinium of the Villa Pulchra. The gold-edged couches were arranged in a horseshoe fashion, and before each was a long, low table of polished Lebanese cedar inlaid with strips of ebony and ivory. The tables were covered with small, fine gold dishes containing portions of beef casserole, hare in sweet sauce, ham in red wine and fennel, fried liver, baked plaice and spiced trout. On a piece of stiffened papyrus, its top and bottom embossed with imperial and Christian insignia, Constantine’s personal chef had explained the menu with phrases such as: ‘If they are young, hares are to be eaten in a sweetish sauce of pepper, a little cumin, and ginger. .’

Claudia had eaten enough, and had drunk the blood-red Falernian wine, at least seventy years old or so the menu declared, mixed heavily with the slightly warm water served to each guest in little jugs. The chamber was lit by chandeliers, each holding six oil lamps in alabaster jars of various colours. The wheels on which these lamps stood had been lowered as far as possible to provide enough light, their fragrance mingling with the perfume from the pots of incense, vervins, maidenhair and frankincense as well as the countless baskets of flowers which ranged along the walls.

The guests had been entertained by various artists and musicians. Now the villa poet was quoting Ovid’s sonnet: ‘Since you are so beautiful, I cannot demand you to be faithful’. Very few of the guests were paying attention, busy with their own conversations or staring rather drunkenly into their cups. In the centre of the horseshoe Constantine was arguing fiercely with his mother. He looked agitated. Helena was holding a water jug, remonstrating with her son about how much he was drinking. Timothaeus was standing anxiously behind the imperial couches. Claudia would have liked to have caught his eye and summoned him over, but the steward appeared ill at ease. Chrysis sprawled, whispering to the pretty boy who shared his couch. Athanasius and Justin, the respective party leaders, were deliberately separated, even though this cosy supper party was being held in their honour. Across from her, Gaius Tullius, his toga slipping on to the floor, yawned in the face of an elderly senator. The Captain glanced quickly across, winked, then turned back to the old fool, who was boring everyone with his denunciations about what was happening in the baths of Rome.

Claudia sat at one end of the horseshoe arrangement. From here she could see the musicians, who had tried their best but had now given up and were gorging themselves on wine and scraps taken from the tables. Directly across from her, at the other end of the horseshoe, was a tall, dark-haired man who had remained silent and tense. Claudia had seen Rufinus get up and go round to talk quietly to him. The stranger was sour-faced, with deep-set eyes, and moved restlessly on his couch. He was not a courtier despite the expensive robes; his face, arms and legs, burnt dark by the sun, glistened with oil. Claudia noticed the scars peeping out from beneath the sleeves and hem of his tunic and concluded he must either be a soldier or a gladiator, as he possessed that same restlessness Murranus did.

Claudia looked away. She was bored, tired, yet still anxious after that violent attack. She recalled the door being opened, the oil lamp tossed in, smashing on the floor to create a puddle of oil and flame. If she had been asleep on the bed, that bowl would have turned the sheets into her funeral pyre. Why had her attacker done this? She closed her eyes and recalled every detail. She had been sitting talking to Narcissus, and the door had opened quickly. That was it! Most of the villa’s guests had retired to their beds during the heat of the day. The would-be assassin thought she would do the same. He had brought that oil lamp, waited until the passageway was empty and opened the door. He had not calculated on someone being with her. He – and Claudia, recalling the grotesque in the cellar, could only conclude it was a man – must have panicked at the sound of voices, and instead of taking more care and aiming the bowl directly at the bed, had simply tossed it in. The assassin had been frustrated, yet had caused enough confusion to send her and Narcissus fleeing through the window. The small chamber was of hard stone, with a few sticks of wooden furniture, so servants had soon brought the blaze under control with heavy cloaks and buckets of dry sand. Claudia and Narcissus had sheltered in the garden. She had told her companion to keep quiet while she informed a chamberlain that the fire was the result of an accident. In truth, however, her tormentor was hunting her, and Claudia wondered if the Augusta knew the facts of the matter. Every so often during the meal Helena would glance across at her, eyebrows drawn together as if curious or perplexed about something.

Claudia gazed around the chamber. Which one of these guests was responsible? Chrysis, who disliked her? The philosophers? Athanasius had approached her just before the meal, rather angry that he couldn’t find his colleague Septimus. Claudia felt tempted to take another sip of wine to calm her nerves, but she didn’t wish to become drunk. Rufinus, on the couch next to her, tried to converse with her, but his wife Fulvia Julia had sensed this and kept cooing like a wood pigeon, demanding her husband’s attention.

Claudia decided to study a painting on the far wall of the triclinium. The dining room was grandly called the Chamber of Mars because its walls were decorated with war-like themes extolling the glory of Rome. The one opposite showed a prosperous country being laid waste. Enemy battalions were being massacred. Men were running away or being taken prisoner, the walls of a town lay smashed by siege engines, its ramparts stormed in a sea of blood, the defenders, unable to resist, lifting their hands in surrender. A cherry hit the table before her. Claudia glanced across. Sylvester was looking at her questioningly, as if he too was curious about the events which had taken place. Claudia gave him a quick smile. The Roman presbyter, like everyone else in this room, was to be regarded with suspicion. Aye, Claudia reflected, not to mention those outside, even woe-faced Narcissus. Claudia pinched her nostrils. There was something not quite right about Narcissus the Neat, something he had said, but she could not place what it was.

The murmur of the conversation died, the poet had withdrawn, having been tossed a silver piece by the Emperor. Chrysis, the chamberlain, took the floor; he was immediately greeted by a round of applause. Claudia suspected what was about to happen. Chrysis was a former actor, a propagandist, ever ready to proclaim fresh scandals about Licinius, Emperor of the East, and his corrupt court at Nicomedia. ‘Fresh news from the East.’ Chrysis spread his hands. ‘Licinius is organising raffles. At his dinner parties he gives out lucky chances written on spoons. It can be ten camels, ten flies, a pound of steak or even dead dogs. I think he is running out of money.’ He gestured with his hands for his audience not to laugh. ‘The man’s mad. He insists on eating fish in a blue sauce. He harnesses four huge dogs to his chariot, and listen, when he gets drunk, he locks his friends in their bedrooms then, at the dead of night, sends in lions, leopards and bears.’

‘I might start that here,’ Constantine shouted in a burst of laughter. ‘What would you like, Chrysis, a bear or a panther?’

‘Excellency,’ Chrysis shook his head, ‘Licinius is bankrupt. He is sending his hangers-on frogs, scorpions, snakes and other hideous reptiles, he is trapping flies in jars and calling them tamed bees.’ Chrysis now had the attention of everyone in the chamber; this was not a game. The chamberlain was deliberately ridiculing Constantine’s rival, raising the temperature of the court, another prick of encouragement for Constantine to try his chances in the East.

Claudia watched the Empress. Helena hadn’t eaten or drunk anything. Claudia suddenly realised someone was missing: Helena’s shadow, the man who had first recruited Claudia for the imperial service, the Christian priest and scribe Anastasius. Why had the Empress left him in Rome? What else was happening? Were there other dangers like those beacon lights? Claudia wondered why the Empress had quarrelled with her son. Moreover, since the poet had left, messengers had been coming in and out of the chamber as if informing Helena about something important happening elsewhere in the villa. Claudia stared round and suppressed a shiver. Helena had taken over the supper party. Before it had even begun she had insisted that everyone had to stay and be entertained. Was there a sinister reason behind that?

‘Licinius is going to die soon.’ Chrysis was now in full flow. ‘It’s been predicted by a Syrian priest that he will die violently. So he has prepared twisted ropes of purple silk so he can hang himself if necessary, and a golden sword on which he can fall when the day of judgement arrives.’ Chrysis was now staring hard-eyed at his imperial master. ‘Licinius expects death. They say he has poisons hidden away in amethysts and emeralds. He has built a very high tower with gold and jewelled slabs beneath on to which he can throw himself. Perhaps it is time, your Excellency,’ he finished with a flourish, ‘that Licinius was encouraged to play more meaningfully with these toys.’

His words were greeted by a thunderous roar of approval. Goblets were raised in toast. Constantine stared round, his heavy-jowled face flushed, nodding in agreement. The musicians struck up a tune, but they were so drunk Chrysis told them to shut up. Rufinus the banker used the occasion to turn back to Claudia.

‘Are you still worried about Murranus?’

‘I am,’ she smiled, ‘and intrigued by what Chrysis said. Did you really think Murranus would kill a man clearly incapacitated?’

Rufinus shrugged. ‘That’s the law of the amphitheatre, Claudia. I’ve seen gladiators trip or fall ill; it’s not saved them from death. But I’ll tell you something,’ he gave a lopsided grin, ‘or I’ll repeat myself. There’s big money being moved around, a great deal going on Murranus to win.’

‘But that’s not the end of it,’ Claudia interrupted. ‘He will have to face Meleager the Magnificent, the Marvel of a Million Cities.’

‘Would you like to meet him?’ Rufinus asked. ‘Meleager? He’s been in the villa since you arrived. Meleager,’ Rufinus called across to the dark-haired stranger Claudia had noticed earlier. ‘You best come over here, I want to introduce someone to you.’

Meleager slid from the couch and came across. He was tall, and just the way he walked reminded Claudia of a panther in a cage. He was thick-set and heavily built but moved as gracefully as any dancer. He crouched down before Rufinus and stared at Claudia. He had deep, close-set eyes, high cheek bones, a slightly twisted nose, and thin lips above a firm chin. His black hair had been cut and dressed to cover a hideous scar close to his left ear. Claudia looked at his wrist; there was no purple tattoo.

‘Meleager, can I introduce young Claudia, messenger and maid of the Augusta, dear friend of Murranus, whom you shall meet in the arena?’

‘My lady.’ Meleager took Claudia’s hand and raised it to his lips. ‘Your friend has won a great reputation. I hope to meet him at the games held in honour of the Emperor’s birthday. My lady, are you well?’

Claudia’s mouth had gone dry. She wanted Meleager to let go of her hand. She didn’t want him to know how cold she had gone. He might not have had any tattoo on his wrist, but up close she recognised that voice, she recalled the smell, a mixture of perfume and sweat; even his touch was familiar. This was the man who had raped her, the killer of poor Felix.

‘I. .’ Claudia’s eyelids fluttered. She prayed she wouldn’t faint. The room was moving. ‘Do you know something,’ she laughed, withdrawing her hand quickly, ‘I’ve drunk far too much wine, I need to be sick.’ And, scrambling off the couch, she fled the chamber.

She didn’t know where she was going. She raced past guards and sentries, ignoring the challenge of an officer. She ran down a colonnaded walk, climbed a wall and fled into the darkness. She reached a tree and felt she could go no further. Her legs were growing heavy and a terrible pain pounded in the back of her head. She felt as if her breath had stopped and, falling to her knees, she was violently sick. As she retched she wiped the hand that Meleager had held, to brush away not just his touch but the very skin. She continued to be sick until her belly was empty; the acid bubbled at the back of her throat but she felt better. She moved away and lay face-down on the grass. It was wet and cool, just like that sand where she and Felix had been playing. He had been hunting for shells when the shadow had appeared. She began to cry, just letting the tears come.

‘Claudia! Claudia!’ She felt her hair being stroked, and tensed. A hand grasped her shoulder and pulled her gently over; she didn’t resist but let herself flop, and stared up at an anxious-faced Sylvester. He took off his cloak, put it over her and sat beside her, plucking at the grass.

‘I saw you leave. The others thought you were going to be sick. Claudia, you are never sick, you are never drunk! What happened there? Meleager thinks he frightened you.’

‘He did,’ Claudia replied, and struggled to sit up. She took Sylvester’s cloak and wrapped it round her shoulders. ‘He terrified me, Magister. He’s the one!’

‘The one?’

‘The man who raped me and killed my brother.’

‘Impossible! You saw the tattoo?’

‘It’s been washed off.’ Claudia felt her strength returning. ‘I know it’s him, I’ll never forget his smell, that voice. .’

‘Hush now.’ Sylvester took her face in his hands. ‘I’m a priest of Christ, Claudia, so what I’m going to say is hard. You must pretend, as you have done since that terrifying night. If justice is to be done, then let God take care of it. I swear by His Holy name that He will. Meleager is a gladiator. If he suspects, even for a few seconds, that you know who he truly is, then you are in very grave danger. No, no.’ He pressed his fingers against Claudia’s lips. ‘Claudia, I beg you by all that is holy, hide your face and curb your heart! I swear that if God does not act, I will. I owe you that.’ He took his fingers away. ‘Think, Claudia,’ he added, his words hissing through the darkness, ‘think of yourself, and of Felix!’

Claudia stared into the night. The pain was going, her stomach was empty and she felt hungry. So many thoughts milled about. Sylvester was stroking her hair just like her father used to. She leaned against his hand.

‘Help me up,’ she whispered, ‘then I’ll help myself.’

Claudia, unsteady on her feet, walked into the darkness and paused. She turned, cocking her head slightly.

‘What was that?’ she asked. ‘Did you hear it, Magister?’ She tried to sift the noises of the night. ‘The clash of weapons, cries and yells?’

Sylvester listened intently. Claudia heard the sounds again. They were coming from somewhere to the south, beyond the villa walls.

‘What is happening?’ She was glad of the distraction. She listened again but the sounds had faded. She recalled those beacon fires, Helena poring over the maps. ‘What is going on, Sylvester?’

‘I don’t know.’ Sylvester shrugged. ‘In the early evening Augusta was very busy. Have you noticed Anastasius is missing? She has left him to watch things in Rome. She has also sent an urgent message to the main German camp not far away. Did you observe her at the supper party? She was very distracted. She didn’t want anyone to leave the triclinium. In fact,’ Sylvester smiled through the darkness, ‘it was she who told me to follow you.’

‘Well, I’m safe and I will go and change.’ Claudia lifted her hand. ‘Sylvester, I thank you. I will act on your advice and,’ she added, ‘keep a still tongue in my head.’

Claudia reached the palace and went straight to her old chamber. Its door hung loose, and one side was badly scorched. She took a lamp and went inside. The floor was covered by a carpet of sand and ash and she had to probe with the half-burnt leg of a stool to ensure nothing was left. She was busy prodding when she recalled the sand in the cellar.

‘Of course,’ she whispered, ‘it must be that!’ She stood staring at the ash, then collected a few items still useable and went along to her new chamber.

Helena had been most generous – this room was more spacious. Scenes from a vineyard decorated the walls: dark green bushes with ochre-red trellises covered with snaking gold branches from which full purple grapes hung. Children collected them in heaped baskets. The painting on the next wall showed the workers in the wine press. Claudia again recalled wading through the sand in that cellar as she tried to flee from her attacker. The stuccoed ceiling was emblazoned with a brilliant picture of Phoebus in his chariot, whilst the mosaic on the floor depicted a young boy playing a flute. The bed was one of the couches taken from the triclinium. The rest of the furniture, stools and small tables, were gifts from the Empress’s stores. New clothes and robes had also been provided. Claudia washed her face in a gleaming bowl, stripped and dressed again. She glanced in the copper-edged mirror, plucked at her cheeks, tidied her hair and sprinkled some of the perfume Murranus had brought her after he had won his last fight.

When she returned to the triclinium, she was relieved to discover her presence had hardly been missed. Athanasius was loudly demanding the whereabouts of Septimus. Chrysis the chamberlain was drunk; he had already been sick and listened bleary-eyed as he shared the couch of the strident orator. Constantine was talking to Rufinus, heads close together like fellow conspirators. Helena was missing. Claudia retook her own seat. She glanced quickly at Meleager, but he hardly spared her a glance; too busy playing the love dove with Rufinus’s wife. Claudia controlled her anger. She felt like crossing the floor and confronting him. Her eye caught a sharp meat knife on the table, and she brushed it with her fingers. It would be so easy to grasp it, run across and plunge it into that bull-like neck! She was about to pick it up when a cherry hit her on the side of her face. She glanced up. Sylvester was staring across, shaking his head.

Claudia withdrew her hand. What could she do? She thought of Murranus moving like a dancer across the sand in the school of gladiators. She felt her empty stomach lurch and a slight flutter of her heart. She pulled across a platter of food, then started at the braying sound of a war horn. The noise and clatter in the triclinium died away. Gaius Tullius sprang to his feet. Constantine lurched from his couch, sitting on its edge, eyes popping, mouth open. The doors were flung open and Helena entered. She whispered to her son, who would have sprung to his feet, but the Empress, standing behind him, pressed firmly on his shoulder.

‘My lords, ladies, fellow guests.’ She smiled sweetly around. ‘The alarm has been raised. This villa is under attack, but,’ her voice rose to a shout, ‘everything is under control. I ask you to return to your own chambers and stay there. My son and I, with others,’ she glared at Claudia, ‘will remain behind.’