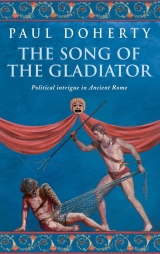

Текст книги "The Song of the Gladiator"

Автор книги: Paul Doherty

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

‘Tell me about the wanderer in the woods,’ Claudia insisted.

‘One of the guards found the old man on the track.’ Timothaeus tapped the left side of his face. ‘He had bruises all along here. Sometimes he was drunk, I thought he’d had a fall or fit. Isn’t that right, Gaius?’

The Captain agreed. ‘At any other time,’ he drawled, ‘we would have tossed such a corpse into the undergrowth, but I felt sorry for him. The villa has a burial pit just beyond the eastern wall. I had the corpse taken to the House of Mourning and wrapped in a shroud. Timothaeus here,’ he added sardonically, ‘as a Christian, claimed it was a pious act to bury the dead, say a prayer and pour a libation over the grave.’

‘Are you a Christian,’ Claudia asked Gaius, ‘or any of your family?’

‘Go through the records, Claudia. I didn’t take part in the persecution, but my family are no friends of the Christians. Nevertheless,’ Gaius patted Timothaeus on the shoulder, ‘some I like. Timothaeus is a good fellow. Anyway, my man declared what he had found, and Timothaeus asked for my help. I had the wanderer brought in; his body was dirty, the head all bloodied.’

‘Could he have been murdered?’ Claudia asked.

Gaius made a face. ‘Possibly. But who would want to kill an old man? All I can remember is that he stank worse than a dog pit. The Emperor arrived in the early afternoon, just after we found the body.’ Gaius moved his head from side to side. ‘It was taken to the death house and then the fun began: Dionysius’s murder.’

‘Timothaeus, you said. .’ Claudia paused; she wanted to be precise as possible, ‘you claimed the wanderer in the woods was a nuisance?’

‘Well, he had been for the last few days before he died. Mistress, I don’t know whether he had a fall or was attacked. I had his body taken up because I felt guilty. The old fellow kept knocking at the gate saying he wished to see the Emperor. I told him to bugger off.’ Timothaeus looked wistfully at her. ‘Perhaps I should have been kinder? We didn’t really look at his corpse, did we, Gaius? The soldiers wrapped him in a shroud, no more than a piece of sacking, put it on a stretcher and brought it in.’

‘Is there anything else?’ Gaius asked.

Claudia stared at the ruined House of Mourning.

‘What sort of people were taken there?’

‘Now and again,’ Timothaeus replied, ‘the occasional guest dies. Anybody with family, well, we hold the corpse until kith and kin come and claim it. As for the rest,’ he rubbed his eyes, ‘usually servants, household slaves. They are put there and later buried or burnt.’ He got to his feet. ‘Now, mistress, I have duties, and so does Gaius.’

They both drifted away. Claudia got to her feet and walked over to the sycamore tree where the Emperor had sheltered on the night of the fire. She walked back to examine the remains of the meal strewn on the hard-packed earth. She also noticed how, here and there, the ground had been dug up, but now it was baked hard.

‘Claudia!’

She got to her feet, brushing off the dust, and peeped around a bush. Narcissus was walking up and down, arms flailing. ‘Claudia!’

‘Just the person!’ she whispered. She stepped from behind the bush and tiptoed quietly up to Narcissus, pushing him hard on the shoulder. He whirled round.

‘I’ve been looking for you, Claudia.’

‘And I’ve been looking for you!’ She smiled back. ‘Come, sit and talk with me!’ She patted his arm. ‘I thought I was a good actress but, Narcissus, your acting ability is equal to mine.’

‘What do you mean?’ he spluttered. ‘Claudia, now is not the time for teasing. I want to know where I’m going to live. How long are you staying at the villa?’

‘Never mind that.’ Claudia gestured to the garden seat. ‘I want to talk to you about the wanderer in the woods. No, Narcissus, don’t start trembling or crying. You knew the old man?’

‘Of course,’ he muttered, avoiding her gaze. ‘Everyone knew him. But I’m frightened. Claudia, what happened last night?’

‘You know what happened, Narcissus: the villa was attacked. The beacon lights? You were the one who saw them, weren’t you?’ She noticed how flushed he’d become. ‘The wanderer in the woods, do you think he was murdered?’ She grabbed his wrist and dug her nails in. ‘Don’t lie, Narcissus. You examined his corpse, as you examine all the bodies taken into the House of Mourning. Some of those you don’t dare to touch, but as for others, don’t you practise your embalming skills on them?’

Narcissus refused to reply.

‘Do you know something?’ Claudia continued blithely. ‘I think you’ve been telling me lies about a lot of things.’

‘I. .’

‘Oh, don’t start acting. You’re an embalmer from Syria who became involved in a revolt and were sold into slavery. Yes?’

Narcissus nodded.

‘You were dispatched to Italy and. .’

‘I came here.’

Claudia slapped his face. ‘I’ll slap you again if you lie. I liked you, Narcissus, but I don’t really know who you are. You’ve been at this villa some time, haven’t you? You know people like Timothaeus. You also know me, and you owe me a great deal, so let’s have the truth.’

‘I arrived in Italy,’ Narcissus began slowly. ‘I was put up for sale in Tarentum.’

‘Capua,’ Claudia interrupted. ‘Don’t forget Capua, Narcissus.’

‘Well, yes,’ he continued hastily. ‘I was sold to a farmer who regarded me as next to useless, so I ended up on the slave block, where I was bought by a Christian family.’

‘Ah,’ Claudia smiled, ‘and you’re a Christian, aren’t you, Narcissus? I’m sure you are a convert.’ She patted his arm. ‘You made a mistake. You actually wondered if there was a different funeral rite for the Arians as opposed to the orthodox. Strange, I thought, how come a pagan slave, a man immersed in the burial rites of Egypt, is so knowledgeable about orthodox Christians and Arians? Who knows,’ she peered at him round-eyed, ‘you may have made other slips.’ Claudia was pleased; she wasn’t ready to confront Narcissus on everything, but her remark had truly frightened him. ‘You were saying?’ she urged.

‘My new master was a funeral manager. He was kindly, with a large family, boys and girls. They lived in a villa on the edge of the town, a lovely place, mistress, gardens and orchards, olive groves and a vineyard. He made his own wine; it tasted very good. I was so happy. What my master wanted, I wanted. I accepted the White Christ. I would believe anything my master did. I was often used by him as a messenger, as a trusted confidant. He admired my embalming skills. He used to laugh, slap me on the shoulder and claim I made the most grotesque corpse kissable. On the Sabbath day, just before the evening meal, his villa became the meeting place for Christians. Their priests, who received what they call the laying on of hands, would come to celebrate the Agape, the Eucharist, what they term the love feast: the breaking of bread and the drinking of wine. They believe it’s the Body and Blood of Christ.

‘Now, my master was very wealthy. He was patron of the oratory school in the town; he liked nothing better than to invite speakers to his villa for the Agape. After the ceremony was over we would have supper out under the stars, the night air sweet with the perfume of hyacinth. The speakers would entertain us debating some topic or other. On other occasions my master would take his entire household down to the school to watch the orators declaim.’ Narcissus put his face in his hands. ‘An idyllic time! Virgil would have sung about it in his poetry.’

‘And?’ Claudia asked.

‘Oh, I met everyone there. The school of oratory at Capua was famous; even Chrysis came, to improve his speaking and public presentation. He considered himself a new Cicero. He loved to quote the Pro Milone or the Contra Catilinam and other speeches of the great orator. I’m not too sure,’ Narcissus screwed his eyes up, ‘I think Chrysis had to leave, some scandal about paying fees, or in his case, not paying them.’

‘And Gaius Tullius?’

Narcissus shook his head. ‘I’ve talked to him. He spent most of his time in Gaul or Britain. He is a pagan through and through and can’t see what all the fuss is about. I never met him until I came here.’

‘And the steward Timothaeus?’

‘He never came, but I understand he had a brother there.’

‘What happened to him?’

‘He disappeared during the persecution. Timothaeus doesn’t know whether he fled, was arrested or killed.’ Narcissus shrugged. ‘No one knows! The rest of the speakers were there, Athanasius, Dionysius and the rest. They were young then, learning the art of public speaking, being trained to deliver a speech with a pebble in their mouth or recite without notes. Looking back, they were all puffed up as barnyard cocks. Justin regarded himself as the new Demosthenes.’

‘You’re an educated man, Narcissus, you know all the names.’

‘My master was a great scholar. He educated me, he let me read his library.’

‘Then it all ended?’

‘Yes, it all ended,’ Narcissus declared wearily. ‘I loved that family, mistress. My master promised me my freedom, planned to have me as a business partner. We could have cornered the trade in that town. You should have seen his warehouses. He had the best funeral paraphernalia: masks, fans, caskets, even his own group of musicians. Diocletian ended all that. He issued his edict, Christianity was once again proscribed, its scriptures and symbols banned.’ Narcissus began to cry, sobbing quietly. Claudia noticed his fists clenched in balls, the veins in his arms standing out like tight cords. This man, she reflected, could kill. And what about Timothaeus? He had had a brother in Capua who apparently disappeared. Chrysis? He was a different matter. He was always known for his sticky fingers, reluctant to pay his debts.

As Narcissus sobbed, he reminded Claudia of a child, his tears being those of anger rather than sorrow.

‘My master’s family,’ he wiped his eyes on the back of his hand, ‘were denounced. The soldiers came in the dead of night, they found a copy of the Christian scriptures, the Chi and Rho and the icthus sign, the fish, the letters of which, as you know, stand for “Jesus Christ, Son of God, Saviour of the World”. I was there shivering in the dark when the soldiers pushed this symbol into my master’s face asking him to renounce it. He refused, as did his family. They were all taken up, bound and tied, pushed out of the door and into a cart. I was ignored; you see, I was a slave, I didn’t exist. I was left like a ghost in that empty house. I stayed there for about four days. People came asking what had happened. I couldn’t believe it! I saw it in their eyes: I was the traitor, I had betrayed my master. So I fled, and hid out in the countryside.’

‘How did you survive?’

‘I knew about the Christian community, names and places. Once I was in hiding, fleeing for my life, I was accepted as one of them, but I faced many dangers. I could be branded as a traitor by the Christians or a runaway slave by the authorities. If I was captured I could expect the cross or end up facing some great bear in the arena. One of the farmers I sheltered with told me how the authorities had now made a tally of my master’s possessions. I was on it but missing. They wanted me.’ Narcissus held his hands up. ‘Mistress, I swear I never betrayed them, but I knew if I was captured I would be tortured. I lurked out in the countryside,’ he blew his cheeks out, ‘oh, two or three years, then I was passed north and given shelter in the catacombs. I looked after the graves of the dead. The years passed quickly. I came to the attention of the presbyter Sylvester and confessed my whole story to him.’

‘I’m sure you did.’ Claudia smiled thinly. ‘And Sylvester arranged for you to come here?’

‘Yes, mistress, because of Constantine’s Edict of Toleration. Our new Emperor made it very clear: runaway slaves had to recognise their status and surrender to the authorities. Sylvester explained he could do nothing for me but soften the blow. He would arrange a good post; sure enough, I was presented to Chrysis and dispatched here.’

‘So you haven’t been here five years?’ Claudia smiled.

‘Of course not.’

Claudia studied him closely. She believed Narcissus was telling the truth, or at least part of it. She could also understand the Augusta’s generosity towards this Syrian embalmer. Helena knew everything and would have learned all about Narcissus’s previous life.

‘You’re a spy, aren’t you?’ Claudia asked. ‘Sylvester made that one of his conditions. Anything you learn you pass on to Timothaeus or someone like me; that’s why you approached me in the garden in the first place. Sylvester does nothing without setting a price, which is always the same: the advancement of the Christian community. It’s good to have a spy at the Villa Pulchra.’

‘Just information,’ Narcissus protested. ‘I know what I saw that night, I mean the beacon fires. I swore an oath of loyalty to Sylvester and I kept it. At that time, sitting out under the stars, I didn’t realise that what I had seen was so important.’

‘Who did betray your master?’

Claudia had deliberately changed the questioning, and for a moment she caught the shift in Narcissus’s eyes, a hard, calculating look. ‘Come on,’ she said, ‘you must have made enquiries. People talk. Names,’ she snapped, ‘you must have overheard names?’

‘Dionysius, Septimus.’ Narcissus was now solemn.

‘Did you dishonour Dionysius’s corpse?’

‘I spat in its face.’

‘What else did you do, Narcissus? Did you examine that old man, the wanderer in the woods?’

‘I. .’

Claudia raised her hand threateningly. ‘He was murdered, wasn’t he?’

‘I think so.’ Narcissus looked away. ‘Yes, I think so. He was covered in dirt and dust, some bleeding to the side of his head. He had thick shaggy hair. His skull was stoved in, but there again, it could have been an accident.’

‘You practise your art, don’t you?’ Claudia asked. ‘You’re an embalmer skilled in the Osirian rites, drawing out the brains and entrails. You did that to the wanderer in the woods, as you’ve practised before on corpses of slaves.’

‘No one knows,’ Narcissus confessed. ‘I felt I had to do it to help them on their journey, and to keep my art alive. What harm did I do? Who cares about some old slave?’

‘You bury the waste in the woods, don’t you? I’ve seen the places where you hide it. More importantly, you had a chest in the House of Mourning filled with resin oil and other combustibles. That was your little kingdom, which is why you never left it. You locked the door and slept underneath the nearby sycamore tree, where you were when the fire broke out. You thought you’d be blamed, so you fled in the night. You were terrified in case they found out what you kept there and what you did. Now, Narcissus, that’s all in the past. On that particular night, did you see anything suspicious?’

‘I was frightened,’ he pleaded. ‘Those orators coming to visit the corpse. . I never expected that. I took a jug of beer and drank too deeply. When I woke up, the fire. .’ He sprang to his feet. ‘I’ve got duties. .’

‘No you haven’t, Narcissus. You are no longer a slave, but a free man.’ She grasped him by the wrist. ‘I have other questions for you, but for the time being, they will wait. Don’t run off.’

Claudia basked in the sunshine reflecting on what Narcissus had said. Slowly but surely she was collecting the pieces. She started up at the clash of weapons. Burrus and a group of his mercenaries came swaggering across, bringing with them a young man. His hair was tousled, and he was dressed in a dark tunic bound round the middle by a cord. Burrus was treating him gently, his great paw on his shoulder, but the young man was clearly terrified, and if the German had taken his hand away he would have bolted like a hare.

‘We found it!’ The Germans ringed Claudia, and the young man they’d escorted fell to his knees before her.

‘Found what?’ Claudia squinted up at them.

‘Traces of camp fires, about two or three men camping out in the woods for some time. A water bottle, scraps of food and clothing.’

‘And who’s he?’

The young man knelt, teeth chattering, eyes all startled.

‘Speak.’ Burrus clapped him on the shoulder. ‘Tell the mistress what you saw.’

The young man gabbled in a dialect Claudia found difficult to follow; she had to ask him to slow down and repeat what he had said. However, he was still distracted by fear, and only when Claudia offered a coin did he begin to talk more slowly. She established that he was a farm worker from a nearby estate who had fled when the attack had been launched on his master’s house. He had come in from the field, glimpsed figures leave the tree-line and race towards the main door of the farm. He had stood terrified as he heard the clash of weapons, the muted screams.

Burrus punched him on the shoulder. ‘No, not that. Tell the mistress what you saw!’

The young man declared how, on the night the House of Mourning had been burned, he had been out in the fields hoping to catch some game. He gave an accurate description of the field Claudia had visited: lonely, lying fallow under the moonlight and ringed by trees. He had been about to cross it when, through the dark, he glimpsed a fire burning. He’d sat and watched it flare, then decided to withdraw and tell his master, but all they found the next morning were burnt embers so they dismissed it as the work of poachers or people hiding out in the woods.

Claudia thanked the young man, gave him the coin and dismissed him. She expected Burrus to move away, but the German stood staring around.

‘Where’s he gone?’ he asked abruptly. ‘The one who walks so quietly?’

‘What are you talking about?’ Claudia replied testily.

‘Gaius,’ Burrus explained. ‘I want to apologise.’ He peered down at Claudia. ‘Gaius is a good soldier, but he is deeply upset that the Empress didn’t trust him. I’ve got to explain.’ He snapped his fingers and left to continue his search.

Claudia stood up, stretched and decided to go back to the villa. She was approaching a side entrance when she heard her name called. Sylvester stood in a portico, beckoning her over.

‘I was hoping I would meet you.’

Claudia leaned against a pillar, aware of its coolness.

‘How do you feel?’ Sylvester sounded solicitous. ‘I mean, about Meleager. Don’t be frightened of him, Claudia. God’s justice is like a hound, it always finds its prey. You’re amongst friends here. Anyway, Meleager has gone, he’s left for Rome.’

Claudia felt herself relax, taking a deep breath. She was dreading meeting that gladiator again.

‘So many unexpected things have happened.’ Sylvester shook his head.

‘Did you plan all this?’ Claudia asked wearily.

‘How could I plan such chaos?’ Sylvester replied, staring over her shoulder. She turned and glimpsed Justin hurrying by.

‘Well?’ She turned back. ‘We have all the people here: Timothaeus, Narcissus, Athanasius.’

‘I never thought murder would join us,’ Sylvester replied, ‘or treason.’

‘Why did you arrange this?’ Claudia asked. ‘Why ask orators from Capua, why not from some other city? There are similar schools in towns all over Italy.’

‘Capua was chosen for two reasons. First, Athanasius is, perhaps, our greatest orator. Secondly. .’ Sylvester caught her by the arm and led her deep into the shadows, ‘Militiades, the Bishop of Rome, had relatives, blood kin, who were caught up in the last persecution. They too came from Capua. He thought the debate might bring the matters to the fore, information might surface, some clarification of what happened so many years ago. So many people died in Capua, Claudia, but that’s in the past.’ Sylvester sighed. ‘Militiades believes we will win the argument. I suppose,’ he added, ‘my Bishop hoped that this debate would show that the Arian party were the House of Traitors and Betrayers, but of course, life is not so simple. I did warn him about that. The persecution is over, but the blood feuds continue.’

‘I know Narcissus is one of yours. The same is true of Timothaeus?’

‘Of course. A good man, very devout. Timothaeus even questions whether he should serve in a pagan household.’

‘You don’t really care, do you?’ Claudia retorted. ‘You and Militiades, you brought people together whose lives are full of shadows and ghosts. You must have known that those shadows would surface. All the rivalry, all the grudges.’

‘I do care,’ Sylvester replied. ‘A purging, a cleansing is very good. The Faith, our religion, must triumph. I said there were two reasons why this debate took place. In truth, there is a third, the cause and origin of it all.’ He curled his fingers into a fist. ‘We have Helena, the Augusta, and soon we shall have her son. Can’t you see, Claudia, the real reason for this debate? We actually rejoice in the divisions, the acrimony, the rivalry. We want it like that. We want the Augusta to intervene, to become one of us, to support the Bishop of Rome. It’s not just enough that Helena supports the Christian faith. Look, there are more divisions amongst Christians than there are fleas on a dog, but Rome holds everything together. One day we want people to see that an attack upon the Church is an attack upon the Empire, whilst an attack on the Empire is an attack upon us.’

Claudia stared at this clever priest who hid a cunning brain behind his gentle face and kind eyes.

‘That’s what it’s all about,’ she whispered. ‘You want Helena to support the Bishop of Rome, right or wrong; you see yourselves as co-Caesars, the spiritual arm of the Empire. Helena will rule in favour of Militiades, and what the Empress says has the force of law. The Bishop of Rome and the Emperor will become indistinguishable. Christianity will be a state religion and Militiades its high priest. Some day you will anoint the Emperor, but you won’t stop there, will you, Sylvester? Everything will come full circle; perhaps one day it will be the Bishop of Rome who decides who wears the purple, who dons the diadem.’

‘Dreams,’ Sylvester smiled, ‘dreams of glory, Claudia, of God’s kingdom being established on Earth. Helena has reached an understanding with us. We want a conclusion that will bind us together. We want her to rule in our favour so our teaching becomes an imperial edict. Now,’ he continued briskly, ‘one thing that certainly wasn’t planned, or expected, was that attack. What have you learned?’

Claudia glanced up at a carving of a face at the top of a pillar, a cherub with pursed lips and full-blown cheeks, its head surrounded by vine leaves. Idly she wondered how many in the villa fully realised what Sylvester was plotting.

‘Claudia?’ Sylvester asked.

‘The attack came from Licinius,’ she replied. ‘He dispatched a galley to the Italian coast but he already had agents in the countryside outside the villa. These lit the beacon fires once they had received the signal from here. The woods are thick and dense, and Licinius’s agents could lurk safely whilst they were waiting for the agreed sign. However, what they didn’t know, what they hadn’t counted on, was the wanderer in the woods, an old man who travelled these parts. I expect he became aware of these strangers and came to the villa to report what he had seen. Unfortunately for him, our traitor or his accomplices learned what he was gabbling about and had him killed. The rest you know: the fires were lit, the galley came in and the troops were landed. Are you pleased, Sylvester?’

‘At an attack on the Emperor? Of course not.’

‘You know what I mean,’ she taunted. ‘Constantine now has a reason for war. Is that part of your dream, your clever design? For Constantine to march east, to issue edicts of toleration there. You’ll be busy then, won’t you, with your legion of agents, stirring up trouble in the eastern provinces, preparing the way for your Saviour?’

Sylvester just laughed, raised his hand in greeting and walked away.

Justin, leader of the Arian party, had seen Claudia and Sylvester close in conversation. He truly wondered what they were talking about but was desperate to reach the latrines. Once there, he was pleased to find they were empty, except for the villa cat, a sinewy black creature which fled through one of the half-open windows. Justin took a seat at the far end, staring mournfully across at the mosaics on the far wall. He did not feel well, his stomach was upset, and the rich food and wine of the previous night had not helped. He was also anxious. He should not have accepted the invitation to this debate. He was trapped. He had come here expecting discussion, but Athanasius was at his best, Sylvester had the ear of the Augusta, and now Justin was caught by ghosts from the past. Athanasius was not only a brilliant orator but also the only one amongst the philosophers who was blameless. After all, as Athanasius liked to point out, after Diocletian had launched his persecution, Athanasius had eventually fled north, well away from Capua, while the rest had been caught up in the net.

Absent-mindedly, still absorbed in the problems that beset him, Justin cleaned himself with a sponge on the end of a stick, and went into the small lavarium to wash his hands and face. He had left the latrines and was passing a low red-bricked building with stairs leading down to a cellar door when he heard a voice echoing up the steps.

‘Justin, Justin.’

He stopped, recognising the building as something to do with the hypocaust; perhaps a place where fuel was stored.

‘Justin.’

He heard a creak and, stepping to his right, peered down the steps. The door at the bottom was now open.

‘Justin.’

The voice was eager, as if the person had found something. So absorbed was he with his problems that Justin forgot about Dionysius, or the fact that Septimus was missing. He went quickly down the steps and through the doorway; he was aware of a lamp glowing, of shadows flickering in the cavernous room. Someone was standing close to a pillar at the far end. He paused, and his assailant struck him on the back of the head.