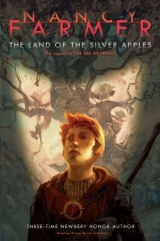

Текст книги "The Land of the Silver Apples"

Автор книги: Nancy Farmer

Жанры:

Классическое фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 22 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

Chapter Forty-six

UNLIFE

They ran down the long stairs and along the halls, passing dungeons that might contain prisoners. Jack remembered King Yffi’s words: Some of our prisoners have disappeared from the dungeons. We find their chains empty, though unlocked.Whatever lurked down here, it was too late to worry about it now, Jack thought as he passed the grim metal doors.

But he realized another problem as soon as the trail began to go down and the light to fail. “Torches!” he cried. “We haven’t got torches!”

“Can you draw fire with your staff?” Pega asked.

“It won’t work without something to burn.” Jack looked around frantically, but the halls were empty.

“I think I can find the way,” said Thorgil. Jack and Pega stared at her.

“It’s pitch-black down there and the trail twists around. Even the Bugaboo got confused,” said Jack.

“Rune taught me how to remember my way in the dark. It’s a little like what he does in the sea.”

Jack remembered, long ago when he’d been a prisoner of the Northmen, how Olaf One-Brow had lowered Rune into the sea. The Northmen’s method of finding land was to go in one direction until they bumped into something, but they had fantastic memories. A beach, once seen, was never forgotten. Water, once tasted, was never confused with water a mile away.

And Rune was the best. He saw the sea as a good farmer saw his fields. He knew the shape of it, its various colors and moods. He observed how the birds lifted their wings as they felt the currents of the sky. He sniffed the air for smoke and fresh-cut peat, for pine and juniper. He tasted the sea itself, to detect the presence of invisible, freshwater streams or of cold welling up from the depths—the result being that the old man always knew exactly where he was.

“You can do what Rune does?” Jack said.

“I have not the years of experience, but he praised my skill.”

Jack looked at the trail going into the dark. It couldn’t hurt to call on other powers, in case they never came out the other end. “May the life force hold us in the hollow of its hand. May we return with the sun and be born anew into the world,” he said, repeating the Bard’s words.

“I shall not return. My hope is Valhalla,” Thorgil said.

“And my hope is Heaven,” said Pega. Then they all joined hands, Thorgil in front, Pega next, and last of all, Jack.

“Like the Bugaboo, I need silence,” the shield maiden said. “I must remember our path.”

They went down into the blackness and, worse, the cold. Chill came up from the ground and down from the ceiling. The walls were so bone-numbing, they seemed to burn rather than freeze when you blundered into them. And everyone did that repeatedly. The going was much slower and harder with Thorgil leading.

Sometimes she had to stop and sense the air around her. Jack didn’t know what she was looking for. Everything seemed exactly the same, but after a moment Thorgil would choose a direction and pull them on.

Jack began to grow sleepy. He stumbled. “Don’t lie down,” Thorgil said. “That’s how the frost giants trap their enemies.”

Frost giants,Jack thought. He remembered the Bard saying something about them.

“I can’t go on,” Pega moaned. “Leave me. I’ll die here.”

“It’s just what I’d expect from a thrall,” Thorgil said harshly. “Very well, die. It’s what creatures like you do best.”

“I’m not a thrall!” said Pega with sudden energy.

“Good. I feel we are passing close to Niflheim. It is the realm of the goddess Hel, and she has a particular liking for thralls. I wouldn’t tempt her with any talk of dying. Now be quiet. I need to think.”

They stumbled on. Jack, too, found it difficult to put one foot ahead of the other. They seemed to have been in the dark for hours. Suddenly, he lurched to the side and fell onto something soft.

Well, not soft exactly, but not as flint-hard as the ground. It made a nice bed.

“Get up,”Pega said in a panicky voice. She clawed at him, trying to catch his arm. Thorgil returned and helped her.

“I bumped into one of those some distance back and led you around it,” the shield maiden said. She didn’t explain. The three of them staggered on, and it seemed Thorgil was getting weak too. Her steps became slower and more unsteady.

“I see light,” said Jack.

“Not a moment too soon. Hurry,” said Thorgil.

Just before the bone-chilling cold lifted, but when the light was barely strong enough to make out the walls, they encountered another strange lump in the tunnel. It was a large, muscular creature covered with fur like a giant otter. Its feet were turned backward, trailing useless claws, and its hands stretched toward the light. But the kelpie had frozen to death before it could escape.

“I suppose they were trying to invade Din Guardi,” Thorgil said.

When they came out to the sea, she collapsed on the ground. Jack noticed she was clutching the rune of protection and her face was drained of color. “You should rest,” he said, concerned.

“I’m ashamed of my weakness,” the shield maiden said. “We were passing close to Niflheim, and I thought if I died there, Odin might never find me.”

“Odin would always find you,” Jack said warmly. “You don’t belong in Niflheim. It would spit you out like a seed.” Thorgil smiled weakly.

They all rested, not saying the one thing that weighed on their minds, that time was slipping by and that the fire pit would soon be ready. Finally, heaving a sigh, Pega climbed to her feet. “I feel like I’ve been beaten all over with a club.”

“Me too,” admitted Thorgil. “There was more in that tunnel than cold.”

Jack did not reveal his theory. He’d been cold many times, but even the ice mountains of Jotunheim were not as terrible as that darkness. Whatever you called it—Niflheim or Hell—that tunnel was the realm of death, not the fate that awaited mortals who trusted in God. It was the utter absence of hope.

They hurried on. The tide dashed itself against the barrier around Din Guardi, and Jack felt queasy as he passed over it again. The country of the yarthkins greeted them with its warm, earthy smells. The air felt green, although, of course, it had no visible color. “I can make a torch now,” said Jack, looking around at driftwood and dried seaweed.

“I don’t think we’ll need it,” said Thorgil.

“You think they’ll come to us?” Jack said.

“If she sings.”

Jack had to fight back a moment of jealousy. His voice was good. It was more than good. It was better than the Bard’s had ever been, or Rune’s. It had pleased the yarthkins once they had arrived. But it was Pega who had called them.

She sang with the voice of the earth itself, with a power bards could only dream of. Jack knew then that he would never be the equal of her. He struggled to rise above the bitterness that filled his soul.

“Sing, Pega,” he commanded her. “Give them the hymn the angel taught to Caedmon.”

She turned toward the warm darkness of a yarthkin tunnel and called, “Erce, Erce, Erce”with her arms outstretched. “Come, oh, come,” she begged, and then she sang. First it was “Caedmon’s Hymn”, followed by a Yule song, “The Holly and the Ivy”. The next offering was “The Wife of Usher’s Well”, about a woman who called her sons home, not realizing they had perished under the sea. And the sons didreturn in the middle of the night, covered with seaweed and clam shells.

Jack thought that ballad might be unwise so near to the Hall of Wraiths. He was happier when she changed to a nursery rhyme. But really, it didn’t matter what Pega sang. All of it was beautiful.

In the distance Jack heard a whispering and a twittering. The darkness in the throat of the tunnel thickened. Something oozed from the walls and fell to the ground with a heavy plop.The hair on Jack’s arms stood up. He grasped his staff and placed himself between Pega and the advancing horde. Thorgil joined him.

Along the floor of the tunnel—and the sides and the ceiling—clustered knots of hair as pale as summer wheat. Long, earth brown fingers pulled them along. Bright, black eyes observed the children with a frightening intensity. Thorgil held her knife in her left hand. Jack had no doubt she could emulate Olaf, if attacked, right down to the kicking and headbutting. “Don’t do anything,” he whispered. “I think they’re friendly.”

“They’re landvættir,” she murmured. “It is always dangerous to draw their attention. Olaf used to remove the dragon head from the prow of his ship when he came to shore, to keep from offending them.”

“I don’t remember that,” said Jack, keeping his eyes on the steadily advancing mass of little haystacks.

“You weren’t paying attention. It’s fine to display the dragon head at sea, but the landvættirconsider it a challenge. By Thor and Odin! Stop touching me!” By now the haystacks had reached Jack and Thorgil, and the pressure of their bodies brought forgotten dreams to the surface. They were the ones Jack tried to forget the moment he woke up, of sinking into mud or being swallowed by a giant snake.

“I’m not your enemy!” cried Thorgil, hurling the knife away. The ring of yarthkins opened out, and Jack breathed more easily. Pega stopped singing. Her face was chalk white.

One of the creatures stood apart from the mass. Jack assumed it was the same one he’d spoken to before and bowed politely. “Thank you for coming,” he said.

How didst thou find Din Guardi, children of earth?the creature said.

“Thoroughly nasty,” replied Jack.

And thy people? How were they?

“They weren’t even there,” Jack said. “My da and the Bard are at St. Filian’s Monastery. So is Brother Aiden. And now our friends are in danger.”

“Please, please help us,” cried Pega, breaking in. “King Yffi is going to kill the hobgoblins. Please—you offered us a boon before. We’re asking for it now. Save them! Save our friends! Destroy their enemies!”

“Be careful what you ask for,” murmured Thorgil.

Shield maiden,said the yarthkin, turning toward the girl. All of his followers did the same with a rustling and a twittering. Thy mother honored us. We do not forget.

“My—my mother?” gasped Thorgil. Jack knew she hardly had known her mother and had been ashamed of her because she was a thrall.

Thy mother asked us to watch over thee. She does so still.

“How can that be? She’s dead! I saw them cut her throat,” cried Thorgil.

We will help thee, children of earth,said the yarthkin, ignoring her outburst. The whole group began to move forward, out of the tunnel and into the muted light of late afternoon. Jack, Pega, and Thorgil were forced to go ahead of them. The thought of being overwhelmed by the little haystacks—of being crept onby them—was more than anyone could stand.

The sea clashed against the invisible barrier. The clouds lowered as though they, too, were trying to break through. Jack and his companions passed over, with Jack being swept by a familiar sensation of dizziness. They turned to look.

The yarthkins were halted at the border.

“Well, that was a waste of time,” said Thorgil.

Pega ran back. “What do we have to do? How can we break the spell that keeps the old gods out?”

Spell?said the head yarthkin. There is no spell.

“We were told about it,” said Jack. “The Man in the Moon did something bad. I don’t know what it was, but he was exiled to the moon, and the rest of you were forbidden to enter his fortress.”

The Man in the Moon wished to rule the green world,said the yarthkin in his whispery, twittering voice. He would have slain all to gain power, and to this end, he made an ally of Unlife. It waswe who exiledhim. But we have not been able to undo his harm. It is Unlife that keeps us out.

“I don’t know how to help you,” Jack cried. “The Bard might, but I can’t get to him.”

Thou hast the means,said the yarthkin, and his thousands upon thousands of followers rustled their agreement. Thy staff drew fire from the heart of Jotunheim. It is a branch of the Great Tree.

“Yggdrassil?” Jack was bewildered. He knew his staff was more than a mere piece of wood, but this? How could he have owned such a thing of power and not known it? And why hadn’t the Bard told him?

Lay thy staff across the ring of Unlife that we may pass over.

Jack paused for a moment. He had a feeling he wasn’t going to like what was going to happen, and he wanted to keep the talisman he’d unwittingly brought from Jotunheim. It was black as coal but hard as flint. He hadn’t used it much, not nearly enough. He didn’t really understand it, although once he’d called up an earthquake with it.

“Jack. Remember the hobgoblins,” said Pega.

The boy shook himself. Of course. Even now, King Yffi’s men might be dragging the Bugaboo and the Nemesis to the fire. He raised the staff and felt the familiar thrum of life within it. Then he laid it across the barrier.

Chapter Forty-seven

THE LAST OF DIN GUARDI

The head yarthkin advanced, pulling himself along by his long, brown fingers. He touched the staff, and Jack held his breath.

The air chimed like a bell. It was as though the sky itself were trembling. The earth answered with a faint thunder. A light as pure as a spring dawn spread over the sea. It flowed up the grim walls of Din Guardi and down into the tunnel. The breeze carried a fragrance that was something like a meadow after a thunderstorm, but much cleaner and fresher.

Green.That was the word for it. The air smelled green, and it made Jack glad to breathe it.

He looked down. The staff that he had won in Jotunheim, the staff that told the world that he, Jack, was a true bard and the heir to Dragon Tongue, had dissolved into ash. Even as he watched, the silvery dust was lifted by the breeze and blown away.

“Here they come!” shouted Thorgil. The yarthkins flowed over the broken barrier in a vast tide. Rustling and whispering, they swarmed past the children. Jack, Thorgil, and Pega clung to one another, scarcely daring to breathe as wave after wave of wheat-colored haystacks surged past them.

This time the dreams they stirred were good, the kind that Jack wanted to remember and that usually melted away when he awoke. He guessed that the yarthkins had been angry before because Thorgil had threatened them with a knife. Now they were joyful. “You’re laughing!” he told Thorgil in surprise.

“You are too,” cried the shield maiden, beaming with joy.

“We all are. Oh, isn’t this wonderful?” said Pega. “It’s like the day I learned to bake bread or when I saw violets for the first time. Or, or—it’s like the day you freed me, Jack, the best day of my life!” Pega threw her arms around him and kissed him.

Jack was startled but pleased, and he kissed her back. Then he kissed Thorgil. They all clung together, transported by delight in the sea, the sky, the earth, and one another.

The yarthkins passed them by and disappeared under Din Guardi. The mad joy that had possessed Jack, Thorgil, and Pega vanished. They glanced at one another with extreme embarrassment. Jack couldn’t imagine what had possessed him, kissing both girls. And Thorgil giggling.They must have all gone insane.

“The clouds have lifted,” said Pega, breaking the awkward silence. It was true. The gray mantle that had blocked out the sun was blowing away, and blue sky peeped out behind it. A wave crashed against the shore, sending spray over the three.

“Looks like the sea isn’t kept out anymore,” said Thorgil. “We’d better run. The tide’s coming in, and unless I’m mistaken, it’s going to flood the tunnel.”

“I don’t know if I can face that cold again,” said Pega.

“It’s either that or drown.”

Jack looked up. The sides of Din Guardi were no longer coated in the pearly light that had come over the sea, and the sun was setting. But the darkening rocks were softened by a glorious full moon rising with the sunset. If stones could be said to look happy, these were happy. Although they’re still too steep to climb,Jack thought resentfully as he followed Thorgil and Pega.

They had a welcome surprise. Nothing was as it had been. Walls were coated with fluttering moss, and the tunnel was lined with the same glowing mushrooms they had encountered before. Not only that, the floor was soft and the air smelled wonderful.

Summer had been let into Din Guardi. No trace of the deadly cold remained. “ landvættirare indeed powerful, if they can drive away Hel,” said Thorgil.

When they came to the upper reaches, where the dungeons lay, they found all the doors open. No one was inside, although some of the manacles looked as though they had once been attached to an arm or a leg. “Do you think kelpies ate them?” whispered Pega.

Jack doubted it. The doors had been too securely locked. He didn’t like the slime trails he saw going up the walls or the way his feet stuck to the floor. Knuckers,he thought, but didn’t say it aloud.

The door to the courtyard was open, with a red glow coming from the fire pit and torches blazing along the sides. A black spit was silhouetted against the flames. “I can’t look. Are they—” Pega hid her face.

“They’re all right.” Jack saw the Bugaboo and the Nemesis with Father Severus and Ethne. And one more person he never expected to meet. “Brutus!” he cried.

“Welcome to Din Guardi! Or as my ancestor Lancelot called it, Joyous Garde. It’s been a while since there was any joy around here.” Brutus grinned infuriatingly. He was still dressed in the golden tunic with the scarlet cape that the Lady of the Lake had given him. The great sword Anredden still hung from that diamond-studded belt.

Pega ran to the Bugaboo and hugged him. “I was so afraid! I thought you were—”

“We’re right as rain, dearest. Only the better for seeing you.” The Bugaboo planted a noisy kiss on top of her head.

“Brutus, why weren’t you here earlier? Why didn’t you help us?” shouted Jack, longing to wipe the silly grin off the man’s face.

“Couldn’t, I’m afraid. Old Yffi tossed me into the dungeon as soon as he saw me. Took away my sword, too, but these chaps got it back.”

Jack looked around to see that the shadows were full of many, many dark lumps whose eyes glinted in the light of the torches. “Yarthkins?”

“Mother used to talk to them all the time. Fine fellows as long as you don’t get on their wrong side.” Brutus signaled, and a very frightened, very repentant Ratface scurried out with a glass of wine.

“I don’t think you even know how to use a sword,” said Thorgil, torn between scorn and laughter.

“That’s not how we Lancelots win battles,” said Brutus, winking. “Anyhow, we were waiting for you to show up so they can finish the job.” He nodded at the silently watching haystacks. They looked as though they might be settled down for a very long time, perhaps centuries.

“What job?” said Jack.

“Long, long ago the Man in the Moon built this place.” Brutus drained his cup and helped himself to a plate of fried chicken held by a visibly trembling Ratface. “Various people lived here after he was driven out, but no one could ever quite relax,if you know what I mean.”

“Not with Hel in the basement,” observed Thorgil.

“Even Lancelot used to look over his shoulder when he went downstairs. Well! Thanks to you, Jack my lad, the ring of Unlife has been broken.”

“I’m not your lad,” said Jack, who was nettled by the casual way Brutus referred to his sacrifice of the staff.

“All trace of the old fortress must be cleansed,” Brutus went on, impervious to Jack’s anger. “I hate to see it come down, but there’s no way we’re going to hold back the Forest Lord. Only the yarthkins have been able to stop him so far. So let us say farewell to Din Guardi. Wine cups all around, Ratface.”

The scullery boy ran to the pantry and stumbled out with an armload of metal goblets and bottles.

“Do theydrink?” whispered Thorgil, nodding at the silent, waiting haystacks.

“Not as we do,” said Brutus. “Ah! This is the fine wine of Iberia. That’s on the continent, I’m not sure where. Yffi and his crowd had all the best stuff.”

They toasted the last hour of Din Guardi, and Jack offered his cup to the one yarthkin who was standing apart from the rest.

Thank thee, child of earth. It was well thought of, though we prefer water,said the creature.

“I didn’t want you to feel left out,” said Jack.

A rippling sound like pouring sand echoed around the courtyard. Jack suspected he was being laughed at. Such as we are never left out,whispered the yarthkin, melting back into the shadows. We will not forget thee.

“And now it’s time to go,” Brutus said cheerfully. “Ratface, you lead the way with a lantern. Thorgil my lad, you bring up the rear.” Thorgil smiled, not at all annoyed at being called “my lad”.

“Stay close to me,” said the Bugaboo, placing Pega between himself and the Nemesis. “I’m not convinced of the Forest Lord’s goodwill.” They went out between waiting clumps of yarthkins and through the front gate. The Hedge loomed ominously against the stars.

“There’s the passage. Don’t wander off, anyone. Nice Hedgy-Wedgy,” crooned Brutus, almost, but not quite, patting the dark, shiny leaves.

Jack didn’t know whether the Hedge was being nice or not. If this was its good behavior, he never wanted to see it on a bad day. The air in the passage was stifling. Thorns and twigs reached out to snag Jack’s clothes and skin. Once, a tendril curled around his ankle before—regretfully, it seemed to Jack—slipping away. And the hostility radiating from the leaves made it difficult to breathe. With one shift, the passage could close in, crushing whatever was within—

Don’t think of it,Jack told himself.

Then they were through, into the clean air with a swath of twinkling stars above and a full moon cresting the top of Din Guardi. A grinding and a crackling told Jack that the passage had indeed closed. “Wait!” he cried. “Yffi and his men! They’re still in the fortress.”

“They have earned their fate,” said Father Severus. Jack noticed that he had the altar cloth from the Holy Isle cradled in his arms.

“The yarthkins sorted them,” Brutus explained. “The rejects were tossed into a storeroom—actually, allof them were rejects except Ratface. Yffi tried to fight, but it isn’t easy to fight yarthkins. Right, Ratface?”

“N-no,” stammered the scullery boy.

“Ratface gave them a bit of a struggle too. I gather it isn’t pleasant being felt all over by them.”

No, indeed,thought Jack, and he no longer wondered at the scullery boy’s terror.

“Let us climb that hill,” suggested Brutus. It was a small hill, and Jack found it pleasant to walk through the feathery grass covering it. Crickets chirped and frogs peeped. It was an ordinary, beautiful summer night.

When he reached the top, Jack could see the dark shape of Din Guardi under the full moon. It seemed larger than he remembered. Then he realized that the Hedge was pressed against the walls.

The Forest Lord attacked.

Rocks groaned as they were wrenched from their places. Wooden doors splintered. Iron grills over windows threw off sparks as they were torn apart. The noise was terrifying and continuous. After a while Jack saw that the fortress was growing smaller.It was settling into the earth like a snowbank melting into a stream. When it was almost flat, the sounds of destruction died away.

If there had been human voices in that turmoil, Jack had not heard them. His heart felt sore. He couldn’t imagine the last moments of the men trapped inside. He regretted the fate of the captain who had admired Ethne and of the man who had lain out all night in the dew to listen to the elves sing. Be careful what you ask for,Thorgil had said.

“There passes the glory of Din Guardi,” said Brutus, standing tall and outrageously handsome under the full moon. “It was a place of shadows and sorrow, doomed in its grandeur and inglorious in its fall. Still, it’s always nice to have a fresh start,” he added, spoiling the noble effect of his speech.

“You’re going to rebuild?” asked Thorgil. The fortress was entirely gone now. Only a stretch of lonely rock jutted out over the sea.

“I am its lord, after all. The Lady of the Lake and her nymphs have promised to help me.”

“I’ll bet they have,” said Jack.

“I’m going to stretch out on the grass for a little shut-eye. It’s so warm, I’m sure we’ll all be perfectly comfortable.” Brutus fell asleep at once, and he was soon followed by the others. It had been a long and dreadful day. Once the danger was past, exhaustion fell on everyone.

But Jack sat up for a while, remembering the staff he had carried from Jotunheim and wondering if he was, in some way, responsible for the deaths of Yffi’s men. The full moon shone down on the sheet of rock that had once been Din Guardi. Jack wondered whether the Man in the Moon had watched its destruction and what effect it had on him.