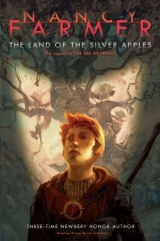

Текст книги "The Land of the Silver Apples"

Автор книги: Nancy Farmer

Жанры:

Классическое фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

Chapter Twenty-six

THE MAELSTROM

Jack, Thorgil, and Pega trudged along in varying moods of gloom. They had spent weeks exploring the cave, always dogged by a pack of hobgoblin youths. They were allowed some freedom, but they were never left entirely alone. Thorgil’s frequent bursts of temper caused the youths to hang back out of range of her fists.

Swarms of will-o’-the-wisps filled the upper reaches so that it was almost as bright as day inside the mountain. But not quite. Something was missing from the light. Jack felt it, though he didn’t know what it was. No leafy plants grew here, no grass or even moss. Instead, the humans and hobgoblins passed through vast fields of mushrooms. Some were as tall as trees with darkness pooled at their base. Even the shadows were wrong. They kept shifting as the will-o’-the-wisps darted around.

The mushrooms were of every imaginable shape and color. They filled the air with a damp, musty smell that Jack found oppressive. He had learned, through Pega’s instructions, not to eat certain fungi. The red spotted ones gave you nightmares, the round purple ones he’d mistaken for plums dulled your wits. The Bugaboo warned her about toxic mushrooms when he remembered and was most apologetic when he forgot. “Humans and hobgoblins don’t eat exactly the same things,” he had explained. “We, for example, dare not touch parsnips. One mouthful makes us itch for a week.”

Suddenly, something punched Jack in the stomach. He folded up on the ground, gasping for breath. “What was that?” cried Thorgil, reaching for her knife and not finding it. “By Thor, I feel naked without weapons!” She tore up mushrooms and hurled them at the invisible enemy.

“It’s the motley sheep,” called one of the young hobgoblins. “Look for shadows that shouldn’t be there.”

Pega knelt by Jack. “You’ll be all right in a moment,” she said softly. “I know how miserable it is to have the breath knocked out of you.”

“Where are these wretched beasts?” demanded Thorgil.

“I… hate…sheep,” wheezed Jack, cradling his bruised stomach. It took him several minutes, but he was finally able to detect collections of smudges hanging in midair. “Why would anyone keep an animal he can’t see?” he asked.

“It’s for the motley wool,” explained the hobgoblin. “It conceals us when we go abroad in the world. You should see the cloaks we make—or, rather, you shouldn’tsee them.” The youth laughed heartily at his own joke. He bounced away from a collection of smudges that was sneaking up on him.

When Jack had recovered, they went on. They were in the deepest part of the cave now, far from any hobgoblin dwelling. Side passages branched off in all directions. It might take years to explore all of them, Jack thought morosely, and who knew what creatures might be lurking in the shadows?

They walked past columns of limestone that glittered eerily in the light of the will-o’-the-wisps. Glowworms dangled on glistening threads. Giant cave spiders scurried into the shadows. “Those remind me of knuckers,” said Pega, shuddering.

“We cleaned out most of the knuckers,” offered one of the young hobgoblins. “The rule is, if a will-o’-the-wisp won’t go inside a tunnel, you’d better stay out too.”

At last they arrived at a black lake filling the farthest end of the cave. Here were no mushrooms or any other form of life, and the will-o’-the-wisps refused to venture over its dark waters. The lake stretched on into ever-increasing gloom until it fell into profound shadow. Jack instinctively disliked it.

“I wouldn’t sail on those waters,” remarked Thorgil.

“The Bugaboo thought you’d like this,” a hobgoblin youth told Pega, pointing at a shelf of crystal jutting out over the lake. It was as clear as glass and no thicker than a crust of ice.

“It’s… impressive,” said Pega. Jack knew she was feeling the same unease he was.

“Walk on it,” suggested one of the youths.

“No, thank you,” said Pega.

“It’s safe as long as you don’t jump up and down.” The creature trotted out onto the shelf and back again. With each step, the crystal chimed a different note. The water shivered in response. A pattern of wavelets rose and formed lines that radiated from the center like the spokes of a wheel.

“That ispretty!” said Pega.

“You can get all kinds of patterns if you walk in different ways,” the hobgoblin said. But still Pega hesitated.

Thorgil, scorning caution, strode out boldly and stamped her foot. “No!” shrieked the hobgoblins, scurrying for the rocks. A single, musical note boomed through the cave. It grew louder and louder, the water heaved, and the center began to sink. The whole lake began to turn.

“Come back!” shouted Jack. Thorgil stood on the crystal with the waves foaming around her boots.

“It’s a maelstrom!” she cried, laughing.

“Get out of there!” Jack ran out on the crystal and dragged her back. Now the whirlpool—or maelstrom,as Thorgil called it—was in full spate. It roared like an angry beast, going round and round as the black hole in its center deepened. Jack couldn’t see into it. He didn’t wantto see into it. He was too busy climbing rocks and helping Pega to higher ground. The hobgoblins gibbered with fear from their perches.

Then, gradually, the water slowed. The roaring faded, and the gaping hole vanished. Only a faint sheen of ripples showed where the whirlpool had been.

“By the nine sea hags, that was a fine adventure!” exulted Thorgil. “This cave is getting me down. Nothing ever happens here. Each day is like the one before, and the same stale jokes are told over and over.”

Jack had to agree. It was all too easy to slide into an endless routine that dulled you as much as the mushrooms he was learning to avoid.

The hobgoblin youths crowded around Thorgil, wringing their hands. “Never stamp on the crystal. Oh, no, no, no,” one of them moaned. “We only tap it, to see the pretty waves. No stamping. Never.”

Now that the lake was calm again, the hobgoblin youths went off to play. They tapped and stroked the crystal shelf to produce beautiful cascades of music. It was a fine performance until they spoiled it by singing. They puffed up like the hobgoblin who had called them to breakfast and produced the most horrible wailing sounds.

Jack, Thorgil, and Pega retreated behind a barrier of limestone, to shut out the worst of the noise. Pega shuddered. “The Bugaboo calls their music ‘skirling’. I think it’s worse than the howling of hungry wolves when you’re alone in the forest.”

“Worse than howling wolves?” echoed Jack. There was something familiar about those words. For days now, certain memories had been hovering just out of reach. “My stars! That’s what Father heard when my sister was stolen!”

And now Jack remembered Father’s description of the little men—dappled and spotted as the grass on a forest floor. They moved around in a dizzying way, first visible, then melting into the leaves, then visible again. They had been wearing motley wool cloaks, Jack suddenly realized! “Hobgoblins stole my sister!” he cried.

“I thought the Bard called the kidnappers ‘pookas’,” said Pega.

“He also called them hobgoblins. How could I have forgotten?”

“My head’s been in the clouds too. It’s those wretched mushrooms. Do you think they still have her?” said Pega.

Thoughts whirled in Jack’s mind. His sister could be hidden anywhere in this enormous underground world. And if he could find her, how could he get her out? For that matter, how could he rescue himself, Pega, and Thorgil? “I don’t know where to begin,” he said.

“Why not simply ask the hobgoblins where your sister is?” said Pega.

“Ask?”cried Jack and Thorgil.

“They mean us no harm.”

“No harm? They only disarm us and keep us prisoner!” said Thorgil.

“I’ve learned a great deal from listening to the Bugaboo and Mumsie,” explained Pega. “I think they genuinely want us to be happy. They may pretend to dislike humans and call us ‘mud men’, but secretly, they admire us. Haven’t you noticed how much this place resembles one of our villages? Hobgoblins copy everything we do. They have the same clothes and houses, the same pastimes and occupations. They can’t grow flowers in their gardens, so they plant red, yellow, and green mushrooms instead.”

Jack listened with amazement. He’d spent so much time searching for ways to escape, he hadn’t paid attention to the hobgoblins. The cave wasa copy of a village. Why have houses with thatched roofs in a place where no rain fell? Why wear hats—as the hobgoblin men did when they gathered mushrooms—when there was no sun?

“Why do they want us?” he asked.

“Because we’re the most interesting thing that’s happened to them in ages,” Pega said. “You must have seen how dull life is here. Nothing ever changes. Mumsie says that’s the bad side of living in the Land of the Silver Apples. There’s a sameness that eats away at life even as it preserves it. Each day repeats itself endlessly until the inhabitants go into a trance from which they can’t be roused. The hobgoblins visit Middle Earth regularly to wake up.”

The horrid skirling had ended, and Jack could hear the hobgoblin youths anxiously calling their names. “We’ll ask about my sister tonight,” he decided. “Pega can soften up the Bugaboo first with her singing.”

Chapter Twenty-seven

HAZEL

That night Pega gave them “The Jolly Miller” and “The False Knight”, followed by “The Man in the Moon”, a song Jack hadn’t heard. The Man in the Moon came down to gather wood for his hearth, leaning on a forked stick as he searched. It was an odd tale and somehow disturbing. Jack wondered where she’d learned it.

“I have sometimes spoken to the Man in the Moon,” remarked Mumsie when the song was finished. “He has much lore for those who can bear his company.”

“He really exists?” said Jack, who had supposed it was only a legend.

“He’s one of the old gods. He’s doomed to ride the night sky alone, and being with him is like being lost on an endless sea with no star to guide you. He visits the green world only during the dark of the moon, and his conversation is both cheerless and disturbing.”

“I wish you wouldn’t talk to him,” said the Bugaboo. “You cry for hours afterward.”

“Knowledge is always gained at a price,” said Mumsie, her eyes blinking serenely. “I gather news of the wide world from the swallows that visit the forest outside. It’s the only way the Man in the Moon can learn of it. In the dark night only owls are abroad, and they’re both stupid and surly.”

Jack’s eyes widened. He remembered the Bard talking earnestly to a swallow in the window of Din Guardi. “Are you—a bard?” he asked cautiously.

Mumsie laughed. “Nothing so grand. I’ve learned a few things from the Wise, but I’m far too lazy to commit my life to such study.”

Jack didn’t believe her. There was nothing at all lazy about the Bugaboo’s mother. It seemed she knew much that she didn’t care to reveal.

“I think we need something cheerful to make up for tales about the Man in the Moon,” said the king. “Give us ‘Caedmon’s Hymn’, Pega my dear.”

She smiled and obeyed. As her perfect voice soared up to a mob of entranced will-o’-the-wisps, hobgoblins began to appear from nearby houses. They came in twos and threes until a dense ring of them surrounded the courtyard. When Pega finished, they all sighed like a wind blowing through a forest.

“You darling!” cried the Bugaboo. “I can’t tell you how happy you’ve made me. Ask for anything and it shall be yours.”

“Now you’re in for it,” said the Nemesis. “She won’t be satisfied until she’s got your heart and liver.”

“First I have to tell you a story,” began Pega. “Long ago Jack’s mother gave birth to a little girl. Unfortunately, she was so ill, the baby had to be cared for by another woman. Later, when Jack’s mother had recovered, his father went off to fetch the infant, and on the way home he stopped to gather hazelnuts.”

At the mention of hazelnuts all the hobgoblins sat up straight and looked attentive.

“He put the infant’s basket into a tree to keep it safe, but then a terrible thing happened. A crowd of little men swarmed up the tree and stole her. Jack’s father tried to catch them, but they were too swift.”

“There you go again,” grumbled the Nemesis, “accusing us of stealing.”

“I didn’t mention you,” retorted Pega. “But you’re right. They were hobgoblins. Jack’s father went frantic with grief, and he knew his wife would be heartbroken.”

Mumsie dabbed at her eyes with her apron. Several women cooed in sympathy.

“Amazingly, when Jack’s father went back to the basket, there was another baby inside. It was a beautiful child—a thoroughly selfish one, it turned out.”

“Lucy isn’t that bad,” Jack protested.

“She could use improvement,” Thorgil said. “She ought to be beaten frequently, as I was, to develop character.”

“I’m not finished,” said Pega, frowning at the shield maiden. “Jack’s father took the new infant home and never told anyone what happened for years. Now I’m coming to my request.” She put her hands on her hips and looked directly at the king. “I want Jack’s sister returned so we can take her home.”

Absolute silence fell over the gathering. Dozens of shiny, black eyes stared at Pega, and nothing moved. Even the will-o’-the-wisps were frozen. Then Mumsie sighed deeply. “I knew no good would come of it,” she said. “I told you, ‘Don’t copy the elves. They’re bad to the bone.’”

“But, Mumsie, I only wanted to give them a taste of their own medicine,” protested the Bugaboo. “I took one of their brats and found an unguarded cradle to leave her in. I thought it would teach the elves how it feels to lose a child.”

“It didn’t teach them a thing,” said Mumsie. “It only gave us the problem of what to do with the baby you took from that cradle.”

Jack hardly dared to breathe. Had his sister been handed over to the elves to become a toddler on a leash?

Mumsie clapped her hands, and a young hobgoblin came up to her. “Go to the Blewits’ house and fetch the human child,” she ordered.

Jack sighed in relief. The hobgoblins didhave his sister and they were bringing her to him now! Events were moving so fast, it made his head spin. What would she look like? What kind of life had she led? A dozen questions occurred to him, but he was too overwhelmed to speak. And so was everyone else.

In the distance Jack saw a male and a female hobgoblin coming down a path that led from a rocky ledge. In front danced a girl still too far away to see clearly.

The crowd around the Bugaboo’s hall parted. The woman hobgoblin was sobbing, and her husband had his arm around her. The girl suddenly halted and ran back to them. They hugged her, each taking a small hand to lead her forward. She was much smaller than Lucy—the size of a four-year-old, perhaps.

“This is your sister,” Mumsie said to Jack. “We named her Hazel.”

The girl looked up at Jack in utter amazement. “A mud man!” she cried. “And there’s more? What a treat! Where did you get them?”

“I never told her the truth,” wept the woman hobgoblin.

“None of us did, Mrs. Blewit,” said Mumsie.

Hazel danced from Jack to Thorgil to Pega. “This one’s pretty,” she said, pointing a chubby finger at Pega.

“Told her what?” Jack was finding it difficult to speak. Hazel was the exact image of Father, right down to his sturdy body and determined expression. Her eyes were gray, not violet, and her hair was brown, not golden as afternoon sunlight. She didn’t float like thistledown. She bounced like a puppy on oversized paws. No one would ever mistake her for a lost princess.

But she was pretty in her own way, with round rosy cheeks and thick, healthy hair that sprang up on her round head.

“We never told her that she’s not a hobgoblin,” said Mumsie.

Jack was astounded. How could Hazel not know she was different from the other children? She must have looked into a stream or noticed that her arms weren’t speckled. But she was very young, and small children might not notice things like that. “Hazel,” he called. She ran to him, and he knelt down beside her. “Hazel, I’m your brother.”

“No you’re not!” She giggled.

“We’re alike. Our hair, our eyes, our bodies are the same. Look at your hands. Your fingers aren’t long and thin. They aren’t sticky at the ends. You’re a mud girl.”

“I’m a hobgoblin, silly, like Ma and Da.” She pointed at the Blewits. “I don’t like you, but I like her.”Hazel went back to Pega, who lifted her in her arms.

“Oof! Heavier than she looks,” Pega said, putting her back down again.

“She’s spent her whole life with the Blewits. They lost their only child shortly before we acquired her,” Mumsie said.

Stole her, you mean,thought Jack. He didn’t say it aloud. He didn’t want to start an argument now.

“If time doesn’t pass here,” he said, reasoning it out, “Hazel should still be an infant. But she isn’t. How is this possible?”

“Do you think we’d keep her shut up like a bird in a cage?” Mr. Blewit said indignantly. He was a thin, gloomy-looking hobgoblin with permanently hunched shoulders. “A sprogling needs fresh air. We often take her into the fields of Middle Earth.”

“And we love it there, too,” said Mrs. Blewit. “We are creatures of Middle Earth, not the Land of the Silver Apples. Sometimes we long to visit the mountains of our youth even though it means we shall age.”

“Many hobgoblins refuse to leave their homelands,” added the Bugaboo. “Kobolds, for example, are perfectly happy in the dark forests of Germany, and brownies cannot be lured from their hearths. We are the only ones who have come here.”

Jack watched Hazel, his mind numbed by the reality of her. She looked human, but she behaved exactly like a hobgoblin. She hopped like one, hooted like one, and gleeped like one. “Gleeping” was a particularly nasty sound the hobgoblins made when they were happy, halfway between a croak and a belch. Hazel was doing it now. “We’ll have to get used to each other,” Jack said.

“Fortunately, we have lots of time,” Mumsie said.

“All the time in the world,” added the Bugaboo.

“No, we don’t,” said Pega. “I asked for Jack’s sister to be returned so we could take her home.”

“You can’t take my baby!” Mrs. Blewit suddenly burst out. “I’ve cared for her all her life and I love her so! Oh, no, no, no, you can’t be so cruel.”

“We can wait a few days,” said Jack.

“A day, a month, a year—it won’t make any difference,” wailed Mrs. Blewit. “I’ll love her just as much then as now. Oh, my darling, my tadpole, my wuggie-wumps, they’re going to take you away!” She hugged Hazel, and the little girl began to cry.

“You can’t have her and that’s flat,” growled Mr. Blewit, smacking his fist against his palm.

“She’s mysister,” cried Jack.

“Stop it right there,” said the Nemesis, coming between the two. “Great toadstools, Blewit, you’re acting like a mud man.”

“I’m sorry, Nemesis, but it goes against the grain,” apologized the hobgoblin. “When we lost our little one, Hazel was the answer to our prayers. I can’t give her up.”

“Let’s all take a deep breath,” the Nemesis advised. “It’s almost time for bed, and I’m sure we’ll see things more clearly in the morning. Mumsie? Did I see a basket of apples in the kitchen this morning?”

“You did indeed,” the Bugaboo’s mother replied. “They’re from the Forest Lord’s best trees (he was busy with the rock slide at the other end of the valley). They’ve been roasted and dipped in honey.”

“Excellent! I’m sure it will do Hazel good to see everyone friendly again. It’s very bad for sproglings when their elders quarrel.” The Nemesis’ eyes were as deep and tranquil as forest pools, and he had a calming effect on everyone.

Jack wondered who actually ruled this kingdom—the Bugaboo, Mumsie, or the Nemesis? Or did they work together at the jobs they did best?

Hazel stopped sobbing and settled down in Mrs. Blewit’s lap. She stuck her tongue out at Jack.

Chapter Twenty-eight

ST. COLUMBA

They sat around the tables drinking cider. The taste was slightly vinegary, but Jack found it deeply satisfying because it came from Middle Earth, not the Land of the Silver Apples. It had come from trees that had slept all winter and were wakened by boys and men shouting waes hael.The chopped-up apples had been fermented in vats of ordinary water. But they had been left slightly too long, and the cider had turned just that little bit sour. It was this imperfection, the evidence of change and time, that Jack relished.

The Bugaboo was gazing moodily at will-o’-the-wisps, and Pega was playing peekaboo with Hazel. The little girl had worked herself into a state of hysteria, bouncing up and down like a sprogling and gleeping when Pega uncovered her eyes. Dear Heaven,thought Jack, how am I ever going to get used to her?

Turning to the Bugaboo, he asked why there was such enmity between hobgoblins and elves. “The elves hate us because we have souls,” the king explained.

Jack listened in fascination as the Bugaboo retold Brother Aiden’s story of the war in Heaven and of how God cast out the angels who wouldn’t take sides. “For long years we lived peacefully with elves,” the Bugaboo said. “Or, rather, they ignored us and we stayed out of their way. They built the Hollow Road to avoid the Forest Lord. He wasn’t above trapping an unwary elf caught hunting in his realm.

“Then the Picts landed in boats and straight off began chopping down trees. The Forest Lord took a terrible vengeance. He asked his brother, the Man in the Moon, to rain madness on their women. Some hurled themselves off cliffs, others drowned themselves in the sea. The men fled underground, where, in the secret places of the earth, they encountered elves.

“They were awestruck,” continued the king. “Or, I should say, they were enthralled,which is a much more serious affair. Most of the Picts came out of hiding and bartered for wives from the Irish across the sea. A few stayed behind.”

“The Old Ones,” said Jack.

“They worship the elves like gods and bring them slaves.”

Jack and Thorgil exchanged a startled look. Jack remembered the slave market so long ago, when the Northmen had tried to sell him and Lucy. He remembered the small men who had seemed like shadows from the forest. Their bodies writhed with painted vines, and their voices hissed like the wind through pine needles. Their leader had wanted Lucy, but Olaf One-Brow had protected her.

“I thought they ate their captives,” said Thorgil.

“Once they did,” the Bugaboo said. “Now slaves unsuitable for elf service are sacrificed to the Forest Lord. The Old Ones seek his friendship, but they delude themselves. The Forest Lord will never be their friend. His hatred is eternal. Slaves are taken under the trees in the dark of the moon. What happens to them there is something I don’t care to describe.”

“I think I know,” said Thorgil, who had turned deadly pale.

“Who wants a roasted apple?” said Mumsie. The hobgoblins eagerly held out their bowls. Mumsie ladled out the steaming fruit drizzled with honey, and a helper topped them with cream. The warm and spicy smells raised Jack’s spirits after the depressing history of the Picts. There had been a gloomy monk among the slaves they had bought from the Northmen. Jack wondered what his fate had been.

The hobgoblins competed to see how many apples they could stuff into their cheeks. The winner managed ten—hobgoblin cheeks were amazingly stretchy. Hazel had to be pounded on the back because she tried to mimic them. My stars, even I think of her as a sprogling,Jack realized. He tried to lure her to him by holding out a roasted apple. She fled at once to Mrs. Blewit’s arms, and he felt both sad and jealous.

“The Picts were followed by the Celts, Britons, Romans, and Saxons,” continued the Bugaboo, tossing the apple cores over his shoulder. “You never saw anything like the Roman army! They swarmed over the hills, clanking and stamping and bawling orders. They cut down trees, built roads, and heaved up walls. If the Forest Lord got a few of them, there were always more behind. He was left only a few untouched stretches of trees, and it weakened him. He draws his strength from them, you see.”

“Now we’re coming to the good part,” interrupted the Nemesis. “The arrival of St. Columba.”

“My ever-so-great-grandparents saw him arrive,” the king said. “He came over the sea from Ireland.”

“In a little coracle,” added the Nemesis, his eyes blinking in a soothing rhythm. He clearly liked the story of St. Columba. “The waves should have dashed it to pieces, but it floated along as peacefully as a gull. Columba spoke to the Picts of strange things called ‘mercy’ and ‘pity’. The Picts laughed merrily and tried to murder him, but Columba blew a wisp of straw into the air.”

“He was a bard!” cried Jack. “That’s how they drive people mad.”

“Whatever he did, it scared the living daylights out of the Picts. They fell on their knees and begged him for this new thing called mercy. So Columba poured water over their heads, and they all became as docile as lambs.”

“My ever-so-great-grandparents concealed themselves in motley wool cloaks to listen to the saint’s sermons,” the Bugaboo resumed. “Then, as now, hobgoblins were not welcome in mud men’s houses. They followed Columba as he walked from village to village, always keeping out of sight. And one dark night my ever-so-great-grandfather got up the courage to approach his window. ‘Please, mud man,’ he whispered. ‘What magic did you use on the Picts?’

“‘Come in by the fire so I can see you,’ said Columba. My ever-so-great-grandfather edged through the door, expecting to be pelted with rocks, as was the custom. But Columba only laughed. ‘You’re a rare one,’ he said. He gave my ever-so-great-grandfather a cup of cider and asked him many questions about mercy and pity. He was impressed with my ever-so-great-grandfather’s answers. ‘I see you’ve been listening,’ Columba said approvingly. My ever-so-great-grandfather admitted to eavesdropping at windows.

“The upshot was that Columba called all the hobgoblins together and baptized them. They stood on the banks of Loch Ness, and one after the other, Columba popped them in. It took seven days and seven nights. At one point a kelpie surfaced and ate a few hobgoblins, but the saint drove him off.”

“Kelpies! That’s the part I hate!” the Nemesis broke in. “They’ll do anything to get at us—climb trees, burrow into the earth, hurl themselves off cliffs. I can’t bear thinking about it!” He had turned pale, and his whole body quivered. Mumsie and the Nemesis’ wife settled on either side of the distraught hobgoblin, cooing and stroking him until he recovered.

“He lost his parents, aunts, and uncles on a picnic at Loch Ness,” the Bugaboo whispered to Jack. “We all try not to mention the K-word around him. To finish our history, Columba assured our ancestors that they now had souls in tip-top condition. And since that time the elves have been our bitter enemies.”