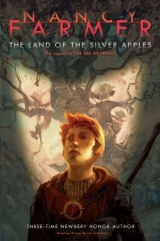

Текст книги "The Land of the Silver Apples"

Автор книги: Nancy Farmer

Жанры:

Классическое фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

It wasn’t a bad dungeon, Jack thought later as he snuggled into a pile of clean straw. They had bedding and water. Father Severus said the Picts brought food regularly. It wasn’t horrible, but it might easily becomehorrible if they had to stay in the dark for days and weeks and months. It was odd how much you missed sunlight when you haven’t got it.

Also, Jack thought, Guthlac took a lot of getting used to. His “Ubba ubba… ubba ubba… ubba ubba”went on all night.

Chapter Thirty-four

THE WILD HUNT

Jack woke. He didn’t know if it was morning or night, but he felt more rested than he had since reaching the Land of the Silver Apples. His sleep had been shallow and unsatisfying in the hobgoblins cave. Glamour must drain your strength. Perhaps sleep did not exist at all in Elfland, where illusion was strongest. A lamp burned in the privy, but the main room was almost completely dark.

Jack cleared a patch of floor, leaving a small heap of straw, and called to the life force. He didn’t need to start a fire. He did it simply because he was comforted by the force’s presence, like an old friend. The straw blazed up, and he saw Father Severus sitting at the table. His face was like a skull stretched over by a thin layer of skin. Jack shivered.

“You’ve learned a trick or two since we last met,” said the man. “You do know wizardry is a sin.”

Once Jack would not have argued with a monk—Father had filled him with awe for such exalted beings—but much had happened since the days when he was a frightened boy being carried to a slave market. He had stood at the foot of Yggdrassil and drunk from Mimir’s Well. “I call to life. Life is not a sin.”

The monk laughed. “Hark at you, lecturing your elders! Life is an opportunityto commit sin. The longer it lasts, the more evil clings to your soul, until you sink beneath the weight of it. Next you’ll be telling me magic is the same as miracles.”

“I was about to say that,” Jack admitted. “They did miracles every day at St. Filian’s, and no one thought twice about it.”

“Those weren’t miracles,” Father Severus said. “Those were vile perversions. They preyed upon the weak and plucked them clean. If I were in charge of St. Filian’s, I’d whip those so-called monks into shape. Hard work and fasting for the lot of them. But we don’t need to sit here in darkness.” He placed a lamp on the table. “None of your magic, please. We’ll use honest flint and iron.”

To Jack, the appearance of fire from pieces of metal and stone was as much magic as the fire he called with his staff. But he didn’t want to argue. Father Severus was a frail, possibly dying, man, and in spite of the monk’s gloomy outlook, there was a deep kindness in him. His reverence for “the simple fact of God’s world” wasn’t that different from the Bard’s reverence for the life force.

“Could you fill the pitcher for me, lad?” asked Father Severus.

Jack hurried to obey. He passed Thorgil, who woke up instantly, and Pega, who had burrowed into the straw like a mouse. Jack could see only the top of her head. When he returned, Father Severus was setting out cups and trenchers.

“The Picts will arrive soon.” The monk smiled morosely. “Occasionally, I tell time by the rumbling of my stomach.”

“Why are they here? The Picts, I mean,” asked Jack. “They don’t seem to be slaves.”

“They’re enthralled,” said Father Severus. “Long ago, when Romans ruled the earth, they fell under the spell of the Fair Folk. These are not ordinary Picts, but the Old Ones who have turned their backs on God’s world. They no longer marry or have children. No mortal woman is good enough for them.”

“If they don’t have children,” said Jack, confused, “why haven’t they died out?”

“You don’t understand. These are the same menwho battled the Romans and fled beneath the hollow hills. They have not aged, except for those rare occasions when they must enter Middle Earth.”

“How… old are they?”

“Hundreds of years,” replied Father Severus. “Do not envy them. Long life has not given them wisdom. It has only allowed them to sink more deeply into corruption.”

Jack felt cold, trying to imagine so much time. One year seemed endless to him. One weekcould drag by if you were waiting for something. Pega appeared from the darkness, scratching her head, followed by Thorgil and Brutus. Father Swein was still holed up somewhere.

“I don’t hear Guthlac. Does that mean it’s morning?” said Pega, yawning.

“Actually, it does,” said Father Severus. “The Picts take him for a walk before they bring food. Otherwise, it’s too difficult getting in and out.”

They heard voices and the sound of the door being unlocked. Brude led the way with a torch. Others brought bread, cheese, apples, and roast pigeons—normal ones with two legs. Brude found Father Swein asleep in a corner and bent over him, whispering, “Ubba ubba.”

“What? What was that? Don’t hurt me!” screamed the priest, leaping up. The Picts roared with laughter.

“You commmme,” Brude said, crooking his finger at Brutus.

“No, thanks,” replied the slave.

“Ladyyyy wannnts you.”

“Ah! That’s different.” Brutus brushed the straw off his clothes and ran his fingers through his hair. “Duty calls,” he told Jack.

“What duty?” said Jack.

“Entertaining Nimue. She must have talked Partholis into forgiving me.”

“You’re leaving us?” cried Jack, irritated beyond belief by the slave’s casual abandonment of his friends.

“Have to, if you want the water back at Din Guardi.”

Brutus went off whistling a maddening tune between his front teeth.

Why haven’t you already restored the water?Jack wanted to ask, but he knew. The man was having the time of his life in Elfland.

The Picts slammed the door. “Witch’s whelp,” muttered Father Swein, piling his trencher with as much food as he could manage.

The joy went out of the room with Brutus’ departure. Jack was annoyed at him, but the slave’s lazy charm had kept everyone’s spirits up. A breakfast in prison with a gloomy monk and a half-mad abbot was hardly a good substitute. When Guthlac was returned shortly thereafter (“Ubba ubba”),Father Swein retreated to the darkness with his trencher.

Jack, Pega, and Thorgil told Father Severus about their adventures. The monk filled his water clock and listened until it ran dry. “No more,” he commanded, holding up his hand. “You have to do things by turns. Otherwise, time will hang too heavily. I personally enjoy prayer interspersed with meditations on sin, but you lack the discipline. Chores are better for young folks.”

“How many chores can there be in this place?” said Pega, eyeing the vast, empty room.

“Dozens,” Father Severus replied heartily. “You can sweep, wash the trenchers, pick fleas out of the straw, measure the floor by handbreadths—”

“Measure the floor?” cried Thorgil. “What good is that?”

“A great deal if it keeps you busy. It doesn’t matter whether work is useful, only that you keep a worshipful mind while doing it.”

“Hel,” muttered Thorgil, swearing by the goddess whose icy halls awaited oath-breakers.

“Hell is exactly what we’re worried about,” Father Severus said. “I’ve seen what happens to monks who have too much time on their hands. Some of them turn vicious, and some”—he nodded toward the shadows where Father Swein was sucking the marrow out of pigeon bones—“go mad.”

Would that be small demon or large demon possession?thought Jack, stifling a laugh.

“I assure you this is a serious business,” said Father Severus, frowning. “We might be down here for years. Or youmight. I won’t last.”

“Yes, sir,” the boy said.

In between chores, the children told stories, exercised, and answered riddles—Father Severus had an endless supply of them. He taught them Latin words and a strange kind of magic called “mathematics”. Six times a day he led them in prayer, except for Thorgil, who said it was beneath her dignity to worship a thrall god.

Without that structure, Jack thought he would have gone insane. The days passed monotonously without the least ray of natural light. It was like being buried alive. Jack snapped at Pega, who didn’t deserve it, and came to blows with Thorgil, who did. Father Severus scolded him. But the monk understood Jack’s despair and set him chores to calm his mind.

Jack was told to capture the tiny animals that fell from the roof and release them into holes in the floor. He didn’t know whether they fared better there, but they were certainly doomed if they stayed in the prison. Father Swein delighted in crushing them. If he captured one alive, he took it to his corner, where the others could hear its pitiful squeaks.

The abbot was growing more dangerous. He demanded most of the food and, because he was the largest, got it. He allowed the food he didn’t eat to rot. The stench poisoned the air, but no one dared to approach his corner to clean it out. At times he swaggered around, threatening punishment to those who defied him. Then the mood would pass, and he would retreat to his corner, uttering loud groans. Father Severus prayed over him, but it did no good.

Thorgil whispered that if he attacked anyone, she would kill him. Jack’s worry was that she wouldn’t succeed.

One day—the sixth or seventh after they arrived—Jack asked Father Severus how he’d found Brother Aiden. They had been practicing “mathematical magic” for two turns of the water cup, and Pega had burst into tears over a problem: If you have ten smoked eels and you eat two the first night and eight the next, how many are left?“You can’t eat eight eels at one sitting,” she sobbed. “They’re too big.”

“Olaf One-Brow could,” said Thorgil.

“Anyhow, you can’t have nosmoked eels,” Pega insisted. “You can have nothing to eat, but you don’t know what it is.” She was having trouble with the concept of zero.So was Jack.

Father Severus announced it was time for stories, and that was when Jack asked him about Brother Aiden.

“I was living in the forest,” replied the monk. “Doing penance, you understand.”

Jack remembered Brother Aiden mentioning a scandal between Father Severus and a mermaid. He longed to ask about it.

“It was a grand place,” said the monk, the memory softening his grim expression. “I had a hut surrounded on three sides by a giant oak, to keep off the wind and rain. The spring-water nearby was as sweet as dew, and in summer the ground was covered with strawberries. In fall I ate my fill of hazelnuts and apples and had enough to store for winter. It sounds lonely, but it wasn’t. Deer, badgers, and wild goats played at my door. The branches were always full of birds.”

“Doesn’t sound like penance to me,” observed Pega.

“I assure you, I was suffering,” Father Severus said. “At any rate, one night I heard the sound of a chase through the forest—at night, mind you, when all good Christians should be in bed. ‘How do they see where they’re going?’ I wondered. The bushes were thrashing, the hounds were baying. I heard men running and the sound of a horn.

“Then I knew it wasn’t a Christian hunt, but something Other. I got on my knees to pray for deliverance, or at least for the courage to bear whatever fate brought me. After a while the Hunt died away. I gave thanks to God for His mercy. And then I heard it.”

“What?” said Thorgil, who had been drawn in by the monk’s vivid description.

“A child crying. Out there where all was wild and deserted, I could hear a small boy weeping as though his heart would break. I took my lamp and searched, but the voice fell silent. He was afraid of me. I had a general idea of his whereabouts, so the next day I put out a pot of porridge.”

“How did you get porridge in the middle of the forest?” said Pega.

“I was allowed to take oats, peas, beans, and barley with me,” said the monk with a slight edge to his voice. “Satisfied?”

Jack nudged Pega to warn her not to interrupt again.

“That night the porridge was gone, and I knew the child was alive.”

“By Freya’s teats, this is as good as a saga,” declared Thorgil.

“I had tamed many a forest creature,” Father Severus said, frowning at the shield maiden’s choice of words. “A child was no different. Day after day I put out food, and I sat under his favorite tree and told stories. He couldn’t understand me—I found that out later—but the sound of my voice must have reassured him. One day he emerged. I didn’t move. I merely sat there and continued to speak. And finally, he trusted me enough to come back to the hut.

“Poor, starved, mistreated child! His body was covered in bruises. His bones stuck out. He was half dead, and when I saw the marks on his skin, I understood.” Father Severus paused to drink some water. He was an excellent storyteller and knew exactly when to stop.

“Understood what?” demanded Thorgil.

“I’m feeling tired,” said the monk. “Perhaps I’ll finish the story tomorrow.”

“You can’t stop now!” said Pega.

Jack noticed a slight quirk at the corner of Father Severus’ mouth. It was how the Bard looked when he knew he’d captured everyone’s absolute attention.

“Are you sure?” said Father Severus, sighing deeply.

“Yes! Yes!” cried both Pega and Thorgil.

“Very well: The boy had the tattoo of a crescent covered by a broken arrow. Below it was a line crossed by five other small lines, the rune for aiden. Aidenmeans ‘yew tree’ in Pictish. The crescent stood for the Man in the Moon and the broken arrow for the Forest Lord. You probably don’t know about them.”

“Oh, we know about them, all right,” said Jack.

“They’re the demons the Picts worship, and that mark meant the child was destined for sacrifice!”

“No!” cried Pega.

“Yes,” said Father Severus. “He was the aim of the Wild Hunt. He’d been intended for death, but he’d escaped. I knew he’d never be safe in the forest. The Picts would return, and so I took him to the Holy Isle. I taught him Saxon and Latin, but I didn’t have to teach him goodness. He already had that. The boy grew into Brother Aiden and became the librarian of the Holy Isle.”

“A wonderful ending.” Pega sighed.

“A better one would have been for the monks to go back to the forest and slaughter the Picts,” Thorgil said.

“Monks don’t do that,” said Father Severus.

“That’s why they’re so easy to pillage,” said the shield maiden with a self-satisfied smile.

Chapter Thirty-five

THE BARD’S MESSAGE

Jack was deeply worried by Brutus’ absence. He’d scratched a mark on the wall for every time the Picts had brought food since their arrival, and now there were fourteen scratches. Two whole weeks had passed since Brutus had been summoned back up to the palace! Thorgil had tried to question Brude and been spat on for an answer.

Jack tracked a meadow mouse through the straw and captured it before it got any closer to Father Swein. He held it gently and looked into its bright eyes. The life force was like a tiny spark in its quivering body. It comforted the boy, and he imagined the mouse’s family waiting for its return. Then he noticed something else.

It had a flower in its mouth.

It was a daisy, the sort of thing that appeared by the thousands in midsummer. Jack had seen them every year of his life but had paid little attention to them. Now, in the darkness of the prison, this single daisy shone like a star. The mouse had been taking it to build a nest.

Jack released the creature into an escape tunnel, but he kept the flower. He sat quite still, and, unbidden, he heard a voice in his mind:

I seek beyond

The turning of a maze

The untying of a knot

The opening of a door.

Dimly, he saw houses surrounded by green fields. Threads of smoke rose from hearth fires, and John the Fletcher called to his dogs as he strode along the road. Such an ordinary, wonderful sound! It made the vision grow brighter and more real. Women sat in doorways, combing wool for spinning. A girl chased an evil-hearted ewe from a garden. Men fitted sections of a cart wheel together with pegs. Jack could hear the faraway tap of their hammers. And all around, fields of daisies stretched as far as he could see.

But this wasn’t where he was meant to be. He turned and found himself in a room. It was a comfortable place with a table and chairs, a brazier for warmth, and beds at the side. A window let in a bar of sunlight, and Jack saw a swallow pecking crumbs from the floor. It looked up at him and warbled, Chirr, twitter, cheet.

You see him, too? Clever bird!said a voice. Jack trembled.

Warble, churdle, coo,said the bird.

He does look the worse for wear, but don’t worry. He is guarded by the need-fire.The Bard stared at Jack through the farseeing tube formed by his hands. Behind him, Father lay in a bed, pale and unmoving, with Brother Aiden at his side.

You have allies you are not aware of,said the Bard, speaking directly to Jack. Remember: No illusion, no matter how compelling, can stand against—

The vision faded. The boy clutched the air to pull it back, but that wasn’t how the magic worked. The Bard was powerful enough to allow him a glimpse of the other side. Jack was nowhere near as skilled. He doubted he could calm his mind enough to even begin the charm, what with “Ubba ubba”in the hallway and Father Swein’s laments.

No illusion can stand against what?thought Jack. The message had ended before that vital piece of information could be given. And what allies did he have in this dark place? Not Brutus, surely! Jack felt absolutely helpless. He could have withstood starvation, beatings, or captivity, but not this false hope. He had no control over anything and no chance of ever escaping. The boy bent his head and gave himself up to despair.

“Come here, Jack,” said Father Severus from the table where he was warming his hands over a lamp.

The boy seated himself and prayed he wouldn’t lose control.

A long silence followed. “Never forget that there is a purpose to everything under Heaven,” Father Severus said at last.

Jack didn’t know what he was talking about.

“If I hadn’t sinned, I would never have been sent to the forest. If I hadn’t been sent to the forest, I would never have saved Aiden’s life,” explained the monk. “If I hadn’t returned to the Holy Isle, I would not have been carried off by Northmen. I wouldn’t have met you or Pega or Thorgil. I was meant to be here, because you needed me. And the three of you are meant to be here for a purpose not yet revealed. But purpose there is.”

Jack swallowed very hard. “You sound like the Bard.”

The monk laughed, setting off a coughing fit. He drank a cup of water to recover. “Don’t insult me by comparing me to a wizard. I’ve heard a lot about your Bard or, as the elves call him, Dragon Tongue.”

“You have?”

“He came here as a young man. He’d been gathering mistletoe on an elf hill when Partholis spotted him. She lured him inside and slammed the door. She was smitten by him, you see, or as much as these soulless creatures can care about anyone. It took Dragon Tongue a year to get away. And when he did, he made off with some of Partholon’s best magic. A fine trick. Notthat I approve of magic,” the monk said.

Jack was enormously cheered by this. Good old Bard! He’d got the better of that nasty Elf Queen.

“What’s that?” inquired Father Severus, pointing at Jack’s hand.

“A daisy. A mouse carried it in.”

“Really?” The monk looked up at the dark ceiling. “I’ve often wondered…” He paused. “The air is always fresh, and sometimes I’ve smelled rain. The mice, the voles, the shrews that fall in…”

“Are too weak to go deep into the earth,” Jack said. “You know, sir, it looked like we were going down when we came here—”

“—but Elfland is full of illusions,” cried Father Severus. “Of course! Why has this never occurred to me? A folk who can make palaces appear out of thin air would think nothing of making us think we were going down, when in fact—”

“—we were going up,”finished Jack.

The two of them gazed at the ceiling. Jack had never considered climbing up because it had seemed pointless. But if they were close to the surface, they could break through and—

The iron door flew open. Jack saw Guthlac pinned against a wall and Brude with his torch. It wasn’t time for supplies. The Picts were here for another reason and probably not a good one. Jack grasped his staff and a trencher to throw if it became necessary. Thorgil and Pega appeared from the gloom. Even Father Swein came out of his corner.

Lady Ethne fled across the room and knelt at Father Severus’ feet. “I tried! I tried!” she wept.

“There, child,” said Father Severus, patting her head. “Tell me what’s upset you. I’m sure talking will help.”

“Nothing can help,” Ethne groaned.

“That’s the problem with getting a new soul,” the monk said gently. “It’s like taking a boat out on a choppy sea. You love too deeply and hate too extremely. You suffer agony from minor slights and are transported by the slightest kindness. It takes time to get used to mortality.”

“It isn’t mysoul I’m worried about,” said Ethne, looking up at Father Severus with her mouth trembling and her eyes brimming with tears. “It’s yours.”

“Mine is in the hands of God.”

“You don’t understand! A messenger has arrived from There. We are all called to Midsummer’s Eve.”

Jack thought Father Severus couldn’t look more ill, but he was wrong. The monk’s face turned as white as parchment, and he trembled. “All must attend?”

“I argued and argued with Mother. I begged her to free you, but she’s dreadfully frightened. She says theyget to choose. She says they get angry if they’re fobbed off with something second-rate.”

“When?” The word was spoken so quietly, it was like the rustle of a candle flame. Jack, Thorgil, and Pega bent closer. It was as though Father Severus had barely enough strength to speak.

“Ssssooon,” said Brude, making them all jump. His eyes were shining like a wolf’s in the forest. He held the blazing torch high and reached out to touch Ethne’s hair.

“Get back!” she cried, leaping to her feet. She turned at once from a frightened girl to the daughter of the Elf Queen. Brude recoiled, holding his hand up as though warding off a blow. “I could have you sent Outside,” snarled Ethne. “I could bar you from Elfland. You could spend the rest of your life lying on a cold hillside, begging to be let in.”

“Nnnoooo,” groaned the Pict, cowering at her feet. Jack was astounded at the change in her.

“Leave us, vile worm!” she commanded. Brude scurried out the door. Ethne immediately reverted to the tearful girl she’d been when she entered. “I shall not desert you,” she whispered, bending to kiss Father Severus’ hand. She left as dramatically as she’d arrived, and the door was bolted behind her.

“Hussy,” said Father Swein, his gaze boring into the spot where the elf lady had stood. “Temptress. Strumpet.” Then his attention wavered, and he retreated to his corner, muttering.

“I don’t see what the fuss is about. We Northmen enjoy Midsummer’s Eve,” said Thorgil. “Olaf One-Brow used to make a great, straw-covered wheel, set it ablaze, and roll it down the hill from King Ivar’s hall. That was to make the trolls think twice about attacking us. On Midsummer’s Eve the mountains open up and the trolls swarm out, looking for a fight. They find it, too, by Thor!” The shield maiden smiled at the memory.

Jack saw she had missed the point of Ethne’s visit. It was no innocent party they were being invited to. You had only to look at Father Severus’ face to know something dreadful was afoot. He remembered the Bard’s words when they were at Din Guardi: Elves don’t welcome visitors except on Midsummer’s Eve.And Brother Aiden’s response: You don’t want to be around then.

“Why is Ethne so upset?” Jack said. “How can there be midsummer, when time doesn’t pass in Elfland?”

“It is midsummer when theysay it is. Time means nothing in Hell,” said Father Severus.

“What are you talking about? What’s going to happen to us?” Pega said shrilly.

The monk took a deep breath and clutched the little tin cross he wore around his neck. “I must set an example for these young ones,” he murmured. “I must not beg for mercy.” He looked directly at Jack, Pega, and Thorgil. “Long ago the elves sought to hold back time, but they didn’t have the strength to do it on their own. They asked for aid from the powers of darkness.”

“Oh! I don’t like the sound of that,” said Pega.

“For such things, there is always a price. The elves drag out their years, aging only when they leave this enchanted realm. In return, on Midsummer’s Eve, they must pay a tithe to Hell. They find a plump, well-nourished soul and bind him over to the fiends. Demons scorn ordinary sinners such as petty thieves. They claim there’s not enough meat on them. But nothing pleases them more than a good man who has fallen into evil ways. Or a woman. They aren’t particular.”

“I’ve been a petty thief. They won’t like me,” said Pega hopefully.

“They’d never be interested in you, child.” Father Severus attempted a smile. It only made him look more ghastly. “The amount of evil you’ve done would barely satisfy an imp.”

“I won’t be chosen,” declared Thorgil. “I serve Odin, not a thrall god who can’t keep order in his own hall.”

“You’ve done crimes and you will be called to account for them,” said the monk, “but not yet. For the Midsummer’s Festival the demons prefer the taste of guilt. They say it adds spice to the dish. You, shield maiden, are as shameless as a Roman alley cat. They won’t choose you either, Jack. In spite of your wizardry, you haven’t used it for evil.”

Jack felt a craven sense of relief. He remembered Father’s stories of demons with sharp claws. “What about him?” He nodded at the dark corner where Father Swein was mumbling.

“Already in the service of the Evil One. They’ll come for him one day, but they prefer to keep their servants on earth to lead others into sin.”

“That leaves only…” Pega faltered.

“Me,” said Father Severus.

“You’re not evil!”

“In my youth I committed an act of great cruelty. I won’t plead ignorance. I knew in my heart of hearts that it was wrong. Now my sin will drag me down to Hell.”

Everyone was shocked into silence. Finally, Pega said, “Did it have anything to do with a mermaid?”

“Be quiet,” hissed Jack.

“I must accept my fate, for it is deserved,” said Father Severus, ignoring the girl’s question.

“Well, we won’t let them take you,” Pega said. “We’ll stand up to those demons and tell them what a good man you are.”

The monk smiled slightly. “I take back what I said earlier, child. You wouldn’t even make an appetizer for an imp. Unfortunately, no one can look upon Hell without being struck dumb with terror. There is nothing worse. Nothing.”

“You mean, we’ll see right into—” Pega began.

Jack shook his head at her. He saw that Father Severus was struggling to appear calm. “Would you like to be alone, sir?” the boy asked.

“Yes! Yes! I must pray!” The monk walked unsteadily into the darkness, and soon there were competing sounds coming from different places: prayers from Father Severus, moans from the abbot, and “Ubba ubba”from Guthlac. They made the atmosphere in the dungeon extremely depressing.

But Jack wasn’t ready to give up yet. He told the others of his belief that they were close to the surface of the earth. “We must dig our way out,” cried Thorgil, seizing the initiative. She immediately dragged the table over to the wall, and the three of them lifted the heavy benches on top.

Jack climbed onto the unsteady heap and began digging a series of holes for them to use for climbing. When he was tired, Thorgil took over. It was slow and exhausting work. Rocks had to be pried out. Dirt fell on their faces. How they would make a tunnel once they reached the ceiling, Jack didn’t know. But they had to try.

Pega sat at the bottom and offered advice. “I think Father Severus is too weak to climb,” she pointed out.

“We’ll carry him,” grunted Thorgil, clinging to the wall.

“I don’t see how. I mean, it’s awkward enough hanging on to those holes.”

“I said we’ll carry him! He weighs no more than a dead dog,” said Thorgil. She attacked the wall with renewed fervor, and the knife clanged against a rock.

“If you’re not careful, you’ll snap the blade,” Pega said.

Thorgil dropped a fistful of dirt on her head. “Next time it’ll be a rock,” she said.

Jack slumped against the wall, resting. Something was different. Thorgil’s knife still hacked at the wall. Dirt pattered down. Father Severus prayed from the left. Father Swein moaned from the right. “Ubba ubba”was missing.

Jack jumped to his feet. The hall was full of tramping feet. The door flew open, and the heap of benches collapsed as Thorgil spun around. She landed easily like the good warrior she was, but the benches knocked the knife from her hand.

A mob of Picts swarmed into the prison. They forced Jack, Pega, and Thorgil into the hallway. They dragged Father Swein from his corner, and two more carried Father Severus between them as easily as a dry twig.

“You commmmme,” hissed Brude.

“I’d rather stayyyyy,” said Jack, dodging a blow, but there was no way he could resist.

It was time for the Midsummer’s Eve celebration.