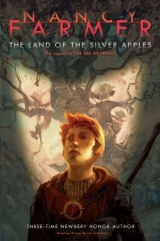

Текст книги "The Land of the Silver Apples"

Автор книги: Nancy Farmer

Жанры:

Классическое фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

Jack wrenched her loose from the bubbling slime and staggered back. The heat was so intense, he was afraid to breathe. “The roof!” Pega cried. Jack looked up. In dozens of places the knobs of jet had caught fire. They burned furiously like a sky full of hot stars. The pillar before the cave went up with a sudden whoosh,making a blaze so dazzling, Jack was stunned. He felt Pega grab his arm. The whole tunnel was ablaze.

They ran. Sand stuck to the slime on Jack’s feet and mired him down. He had a stitch in his side. He thought his knees would collapse, and still he ran, pulling Pega along. When at last they fell, gasping and coughing, to the ground, Jack could hear the roar of the flames behind them. A dire light flickered on the walls. “Is it coming?” Pega said fearfully.

Jack braced himself for another effort, but as the moments passed, the light grew no brighter and the roaring no louder. “The wind is blowing it away,” he said. And, indeed, the fire drew air toward it so fiercely, a near gale moaned down the passage. A distant rumble told Jack that something had collapsed. “We can’t stay here. Can you walk?”

“An hour ago I’d have said no,” admitted Pega. “Amazing what mortal terror can do.”

Jack nodded soberly. They went on again, slowly, with the sand weighting down their feet. The light faded until it died away altogether, and they had to feel their way along the wall.

“The food’s gone,” Pega said.

“The cider, too,” said Jack.

“I’m trying not to think about that.”

“Would you believe it? I’m cold,” said Jack. The wind had a touch of ice that went straight through him. His cloak had been with the carrying bags and was now ashes. “If we found wood, I could start a fire.”

“Don’t you dare!”

They trudged on, following the wall. Jack probed the ground ahead with his staff. His feet were scorched, and he guessed Pega’s were too. He wondered what the bats would do when they tried to fly back up the passage. On the positive side, the fire must have cleaned out the wyverns, hippogriffs, cockatrices, manticores, basilisks, hydras, and krakens. And knuckers.

Especially knuckers.

“Where do you suppose Brutus got to?” Pega said.

“I wonder,” said Jack as all his bitter suspicions of the slave rushed back.

Chapter Twenty

THE ENCHANTED FOREST

“I wish I could light my candle,” murmured Pega, lying on the sand.

“What candle?” said Jack, lying beside her. Exhaustion and thirst had finally overtaken them. Jack thought he could struggle on, but Pega was clearly at the end of her strength.

“The one your mother gave me.”

“You still have it?” said Jack, surprised.

“Of course. It was given to me on the best day of my life. The day you freed me.”

Jack knew she always carried it in a string bag tied to her waist. He thought it had been lost with all their other possessions.

“Your mother said, ‘When you feel the need, it will brighten your nights.’ And I said, ‘When I die, I’ll be buried with it.’ So I shall.”

Jack felt the prickle of tears. He was too dried out to produce them. “I’m surprised it survived the fire.”

“Me too. It’s slightly flattened.” Jack heard Pega moving, and presently, he felt something brush his face. He smelled the honey-sweet wax. “Isn’t that wonderful?” the girl said. “It’s like being outside.”

Jack remembered how Mother talked to the bees, telling them what was happening in the village. Bees wanted to know everything, she said, and for the first time the boy wondered if she was also listening to them. Mother sang when the weather was thundery, to keep the hives from swarming. “Sitte ge, sigewif. Sigað to eorpan,”she sang. Settle, you warrior women. Sink to the earth.

It was her small magic. It wasn’t as impressive as the Bard’s large magic, for he could call up storms and drive people mad, but it might be just as important. Jack hadn’t thought of that before. Pega’s candle, gathered patiently in field and meadow, had its own quiet power. It, too, had drawn fire from the earth.

He blinked his eyes. A pale, blue light hung in the distance. The hair stood up on his arms. He felt for his staff.

“Is it a ghost?” Pega whispered.

The blue light neither advanced nor retreated. It simply waited. Is Brutus dead? Has his spirit come back to haunt us?thought Jack. But, no, if it were Brutus’ ghost, it would be moaning. The boy smiled in spite of himself. The light didn’t move, but it became brighter. All at once Jack understood what he was seeing.

“It’s the moon! I’m such a fool!”

“What?” Pega said drowsily.

“We’re there! That’s the entrance. Come on, Pega. You can make these last few steps.” He pulled her up and half dragged her along the sand. When they got to the light, Jack saw it was falling from a hole at the top of a heap of rocks. That was why he hadn’t seen it before. The moon had to be in exactly the right place to shine down.

“You go. Tell me if it’s nice.” Pega collapsed on the sand.

“I knowit’s nice. Come on!”

“Too tired.” She sighed.

Jack knew he couldn’t carry her. “I can’t leave you here for a knucker to find.”

“A knucker?”

“That thing we saw in the cave.”

“That,” said Pega with slightly more energy, “was a giant bedbug.”

“It was a tick,” said Jack, who hated ticks.

“It was a bedbug.A bedbug! I’ve seen thousands of them, only not so… huge.” Pega’s voice was edged with panic.

Jack thought for a moment. “There could be hundreds of them down here.”

Pega grabbed Jack’s arm. “You’re making that up.”

“It makes sense that there’d be more than one of them. Everything comes in pairs, and some creatures have a lot of babies.”

Pega pulled herself up. “You’ll have to help me,” she said tensely. “I don’t know if I can make it, but I’d rather fall and break my neck than…” She didn’t finish, but Jack understood what she meant.

The rock pile wasn’t stable. More than once a boulder shifted and sent a cascade of dirt and pebbles over them. More than once Jack and Pega had to cling to the side while they waited to see whether the whole pile would come down.

But at last they struggled out onto a steep hillside. They lay panting and stunned under a sky strewn with stars. A full moon hung overhead and painted the rocks with a lovely blue light. From below, where giant trees stretched their branches over unseen dark glades and meadows, came the music of a rushing stream.

The air was surprisingly cold, though its freshness made up for it. Jack had been in the fug of bat guano so long, he’d forgotten how good clean air could be. He breathed in long drafts of it, but as delightful as it was, it of course couldn’t take the place of water. “It isn’t much farther,” he whispered to Pega.

Jack saw that they were halfway down a vast rock slide. An entire cliff had collapsed, sending stones and dirt all the way to the edge of a deep forest. The boy and girl slid down on loose gravel, occasionally coming to rest at giant boulders that stuck out like plums in a pudding. But it was far easier going down than up. The moonlight shone all around with a dreamlike radiance, so bright the hillside seemed to glow.

At the bottom they came to a narrow strip of meadowland before the trees.

“Ohhh,” said Pega, sinking her scorched feet into grass. Buttercups, oxeye daisies, and primroses spread out in drifts, though their colors were hidden in the silvery light. Beyond, complete darkness loomed, and in that darkness the water sang.

“Do you think there’re wolves?” whispered Pega, pressing against Jack.

�It doesn�t make any difference. We have to go,� the boy said. They edged through the cool grass, Jack in front with his staff at the ready. He heard nothing except the stream, yet he felt a watchfulness in the air. I wish I had a knife,he thought, but his knife had vanished with the rest of their supplies in the fire.

“It’s so dark,” Pega murmured.

Jack thought about shouting for Brutus—he must have come this way—but the watchfulness made him hesitate.

Only a dim echo of moonlight penetrated beyond the edge of the forest. Roots snaked around humps of moss, and branches twisted awkwardly. They seemed, to Jack’s mind, to have frozen into place and were waiting for him to look away before moving again. He listened for the usual night sounds—frogs, crickets, or even an owl muttering as it glided after prey. There was nothing except the stream. “Well, here goes,” Jack said.

He advanced carefully with Pega clinging to his arm. “We’ll never find each other again if we get separated,” she whispered. Jack thought it unlikely they’d get separated. She was holding him so tightly, he was sure there’d be a bruise in the morning. Once the light faded, they had to feel their way along with only the sound of water to guide them. Jack tripped over a root, and they both blundered into stinging nettles.

“Ah!” Jack cried, pitching forward. Pega’s firm grip saved him. The ground was slippery with mud.

“There’s gotto be water,” she moaned. Jack inched ahead on his knees. He saw a glimmer of light and recklessly tore away vines.

“Oh, sweet saints,” Pega said reverently. The trees parted to show a rushing stream, marked here and there by slicks of moonlight. It flowed noisily over rocks and on into a broad channel, a dark presence slicing the forest in two.

Jack and Pega slid down the bank as fast as they could go and landed in the water up to their waists. The current was deeply cold. Jack didn’t care. He drank until his head ached and his stomach cramped, but the water took away the pain in his feet.

Finally, they crawled back up the muddy bank and snuggled together like a pair of foxes in a tree hollowed by age. They were wet, cold, and very, very hungry, but the sound of water sent them to sleep as surely as if they were in the Bard’s house with a fire snapping on the hearth. They slept through the night and the dawn as well. It was mid-morning before they stirred and saw the sun sending narrow beams of light into the forest outside.

“Where are we?” said Pega, shading her eyes.

“Here. Wherever hereis,” Jack answered, yawning. The air shivered with tiny midges dancing in the light that penetrated the forest. The stream tumbled nearby, and a carpet of wild strawberries covered the ground around the hollow tree. “Food!” Jack cried.

They picked the tiny fruit as fast as they could. “Mmf! This is good! More! More!!” Juice ran down Pega’s chin and dripped onto her dress.

“You know,” said Jack, sitting back after the first ecstasy of filling his stomach, “it’s awfully early for strawberries.”

“Who cares?” Pega wiped her mouth with her arm.

“It isn’t even May Day. There should only be flowers.”

“Then we’re lucky,” declared Pega. “Brother Aiden would call this a miracle.” She began gathering strawberries again.

Jack was uneasy. Several things bothered him. The fire he’d called up in the tunnel had come too readily—not that he wasn’t grateful. He didn’t want to find out what knuckers ate for dinner when they couldn’t find bats. But in the village fire-making was difficult. You had to clear your mind and call to the life force. You couldn’t just snap your fingers.

The moonlight, too, had been odd. He’d been too tired to care last night, but now it came back to him. Everything seemed to glow.And now the strawberries. Not one of them was green or worm-eaten or overripe. “This place is like Jotunheim,” he said.

“From what you’ve told me, it’s a lot nicer than Jotunheim.”

“Parts were horrible. Others…” Jack’s voice trailed off. There was no way he could explain the wonder of Yggdrassil to someone who hadn’t seen it. “Anyhow, magic is what I’m talking about. It’s close to the surface here, and dangerous.”

“Dangerous?”

“Like when I called fire. I couldn’t stop it.”

Pega looked around. The trees were covered in thick moss, like sheep after a cold winter, and clusters of bluebells grew at their feet. The ground was a carpet of strawberries. Toward the stream was a swath of yellow irises. “All right. I agree. It does look a little too perfect. Are we going to have trolls stomping around demanding our blood?”

“Not here. It’s too warm. But what,” Jack hardly dared say it, “if this is Elfland?”

Pega’s eyes opened wide. “Crumbs! It’s pretty enough.”

And wet enough,thought Jack. If ever there was a place the Lady of the Lake would love, this was it. “Brutus must be around somewhere. I wonder why he isn’t calling for us,” he said.

“We haven’t been calling him, either.”

“No,” said Jack, once more aware of a watchfulness in the trees. Sometimes it seemed far away, concerned with other things, and sometimes it was right there next to them. “I haven’t seen a sign of him, though he must be around. Unless he’s dead. That would be a problem.”

“It’d certainly be a problem for him,” Pega said.

“I’m not being heartless. Of course I’d feel sorry if anything happened to Brutus, but we were counting on him. I suspect he’s done something stupid, like challenge a dragon and got himself eaten.”

“Inconsiderate of him.”

“Do we keep exploring?” Jack said, ignoring her sarcasm. “We could wander for weeks. Or do we go back down the hole and choose another tunnel? The fire must be out by now.”

“Go back down?” Pega turned very pale, and her birthmark stood out like ink. “I wouldn’t want to meet another of those—you know.”

“Me neither.”

“Well then.”

They went back to the meadow. By day the hillside appeared an even greater ruin. A huge section of cliff had fallen, leaving a giant scar on the mountains above. The slide went halfway up and ended in rocks too rugged to climb. “This looks new,” said Jack, shading his eyes. “I wonder if it happened during the earthquake.”

They followed the edge of the meadow, fording little streams that poured out of the mountainside, keeping the grass to their left and the rocks to their right. Deer watched them gravely from the shadows of the trees, and red squirrels followed them with bright, black eyes. Voles, dormice, and shrews rummaged through the flowers, unworried by the appearance of strange humans. Even hedgehogs were foraging.

“That’s another thing that just shouts magic,” Jack pointed out. “Hedgehogs in daylight.”

“I could catch those,” Pega suggested. “You roast them coated in mud and the quills come right off.”

“You aren’t allowed to hunt in magic places,” Jack said decisively.

“We’ll need something. Those strawberries wore off hours ago.” Eventually, Pega found a field of pignuts. She pulled them up and collected the round nuts on their roots. “I used to eat these when my owners didn’t feed me,” she explained. Jack decided they weren’t too bad—like hazelnuts dipped in mud. Besides, he had nothing else.

The sun sank behind the mountains. Blue shadows flowed over the forest, and the temperature dropped. They hurriedly tried to gather firewood, but strangely, the forest produced nothing but a few twigs and damp leaves. The ancient trees clung on to every gnarled branch. “Doesn’t anything diehere?” Pega cried.

“Not if it’s Elfland,” Jack guessed. The light was fading, and his teeth chattered with cold. They would have to find shelter or freeze to death. They searched until they found a ring of trees so close together, the trunks formed a natural room.

“Can’t you use your staff to call up fire?” Pega said, stamping her feet and rubbing her arms to keep warm.

“Even magic fire needs fuel. Somehow I don’t think it’s safe to burn these trees.”

They were exhausted from walking, but sleep would not come. A chill came up from the ground, and neither Jack nor Pega cared to snuggle close to the roots. Jack was aware, though he couldn’t say how, of a brooding dislikein the trees. They seemed to be making up their minds about what they might do with the intruders in their midst.

“That does it,” Pega said, sitting up. “I’ve had it with those trees whispering.”

“What whispering?” said Jack, jarred from what little comfort he had.

“Those sneaky sounds. Surely you heard them? I don’t know what they’re saying, but I don’t like it. What did Brutus tell us to do when we were dispirited? Sing something cheerful.”

“You mean his ballad about a knight hunting an ogre in a haunted wood? Remember how it ended?”

“Not thatone,” Pega said. “The one your father sang on the way to Bebba’s Town.” She immediately began Brother Caedmon’s hymn, given to him by an angel in a dream.

Praise we now the Fashioner of Heaven’s fabric,

The majesty of His might and His mind’s wisdom…

Jack had to admit it was an excellent choice. For one thing, its soaring power put those whispering trees in their place. Jack couldn’t hear them, but he didn’t doubt that Pega could. For another, her voice was so marvelously fine. He’d been jealous of her at the Bard’s house, but he knew even then he was being unfair. She wasn’t a strong singer, yet her music filled the night. In the darkness you could believe you were listening to an elf lady.

Afterward they curled up together as they had in the hollow tree. No looming menace disturbed their sleep, and when they awoke, they found themselves covered with a blanket of the finest wool.

Chapter Twenty-one

THE GIRL IN THE MOSS

The little hollow was filled with a dim, green light. Jack could see sunbeams in the distance, but here the branches formed a dense mat. The air was heavy with the scent of lime flowers, and above, unseen, hummed a multitude of bees. For a moment Jack thought they had found their way into the Valley of Yggdrassil. But the hum wasn’t frenzied as it had been there. It was merely the sound of bees going about their usual chores.

“Where did this blanket come from?” whispered Pega.

“Elves?” guessed Jack.

“Brother Aiden said elves were completely selfish. Someone else left this, but what kind of people creep up on you in the middle of the night?”

“Maybe Brutus found a village and borrowed some things,” Jack said doubtfully. “I could shout for him, but—”

“It doesn’t seem quite safe,” Pega finished.

“He’s gotto be here somewhere. He probably went to the stream to fill the empty cider bags,” said Jack. “He would have returned for us, unless…” Unless he never got out in the first place,the boy thought. But, no, they would have heard Brutus shouting if anything had gone wrong. It wasn’t like the slave to go quietly into a knucker hole.

The trees weren’t as threatening as they had seemed the night before, but they still made Jack uneasy. “This is an odd kind of wool,” he said, feeling the fine, soft weave. From underneath, it was visible, but when he spread it on the ground, it vanished.

“It’s magic,” Pega said. “I’ve heard about cloaks of invisibility in stories. We’ll have to be careful, or we’ll lose it.” She folded it up and put a rock on top to mark its position. “Look!” she cried. She pounced on what Jack had thought was a large mushroom bulging out of the tree roots. The top of it came off, and a delicious smell wafted through the hollow. “It’s a pot and it’s full of bread and the bread’s still warm!”

Jack was by her side in a flash. “There’s more,” he said in wonder. Other mushroom-shaped containers revealed butter, honey, and golden rounds of cheese. The invisible creatures had even thought to provide wooden butter spreaders.

“Oh, thank you, thank you, whoever you are,” called Pega. “I swear I’ll do something nice for you, just name—”

“Hush,” said Jack, covering her mouth. He knew from stories that it was dangerous to make promises to things you couldn’t see. “We’re both extremely grateful,” he said, formally bowing to the trees around. “We’d be really happy to share this meal with you.”

But the forest was silent except for a faint breeze working its way through the branches and the bees humming all around. In the distance an unknown bird warbled and trilled.

Pega tore the bread apart and slathered it with butter and honey. She passed a chunk to Jack. “Do you think this food is enchanted?” he said, pausing with his hand in midair.

“I don’t care!” Pega bit into her chunk and added, in a muffled voice, “You can wait to see if I turn into a grasshopper. At least I’ll be a well-fed grasshopper.”

Jack couldn’t resist the smell of melting butter. He began devouring the warm bread, and it was even better than it smelled. The honey was as fragrant as a field of clover, and the cheese was sharp and wonderfully satisfying. He stuffed two rounds of it into his pockets for later.

When they were finished, they sat back in a kind of happy daze, too contented to move or talk. “We ought to wash our hands and faces,” Pega said after a while.

“Hmm,” said Jack. They sat a while longer, until the sound of a little, bubbling stream roused them. “I could use a drink,” Jack murmured.

“Me too,” said Pega. Time passed.

“We should move,” Jack said. He forced himself to rise. The green stillness of the hollow lay heavily on his body and urged him to lie down again. It’s a fine old bed, earth is,whispered a voice in Jack’s mind. You can pull the moss over you and sleep for a hundred years.“Get up,” cried Jack, suddenly alarmed. He dragged Pega to her feet and forced her to walk around. Once they were out of the hollow, Jack stamped his feet to get feeling back into them. Pega slapped her arms.

“What was that?” she said, her eyes wide and frightened.

“I don’t know. The trees, maybe. I never trusted them.”

They walked to the stream and washed their faces and hands. The cold water revived them.

“We mustn’t get too comfortable,” Jack said. “When I was in the Valley of Yggdrassil, I lost all track of time.” He stopped and remembered the drowsy enchantment of that place. He’d still be there if it hadn’t been for Thorgil. “We’ve got to remember our mission. Everyone’s depending on us. We have to find the Lady of the Lake and bring the water back to Bebba’s Town. King Yffi won’t wait forever.”

“That’s funny. I completely forgot about Yffi.” Pega waved her hand in front of her face as though brushing away spiderwebs.

“Magic does that. We have to keep reminding ourselves why we’re here. We have to keep saying people’s names. If I forget, you remind me.”

Pega fetched her string bag and removed the candle Mother had given her. “Smell,” she commanded.

Jack did so, and his head cleared at once. He remembered the village with its fields and houses. He saw the blacksmith fashioning a farm tool on his anvil, the baker pulling bread from his oven, and Mother sitting at her loom.

“You see,” Pega said, sniffing the fragrant wax herself, “the need-fire came through this. It will light our way back home.”

“You’ve learned more than I realized,” said Jack gravely.

“I listened a lot. Slaves do,” she replied.

They went back to the hollow to retrieve the blanket, but it was gone and so were the pots. “I suppose the owners took them,” said Pega. “It’s only natural. Now what do we do?”

Jack hung his head, trying to come up with a plan. “I wish I knew where we were,” he said. “Maybe the Lady of the Lake is here, and maybe she isn’t. Brutus could have found her, or he might have stumbled onto a dragon. We definitely can’t go back down that tunnel.”

In the end they kept on walking, keeping the trees to their left and the mountain to their right. They passed ghostly birches, aspens with leaves that twinkled in the wind, giant oaks with moss trailing like hair, and monstrous yews. The meadow through which they traveled was alive with small animals. Once, they saw a lynx watching them with round yellow eyes, and another time they crossed a stream where green butterflies drifted to and fro over banks of valerian.

It was a surpassingly beautiful place, yet ultimately, it was disappointing. They found no trails and saw no houses or the smoke that would come from houses. “Where are the people?” Pega said. In late afternoon they came to a rift in the trees where a tongue of rock jutted out of the mountain. They walked along the top.

“This wouldn’t be a bad place to camp,” Jack said.

“Too cold,” said Pega. “Imagine how exposed we’d be.”

“It’s better than sleeping in the forest.” Since that morning Jack had developed a dislike for trees. Roots snaked to the very edge of the rock as though trying to climb it. Moss humped up in patterns suggestive of buried bodies, though Jack guessed it was only more roots underneath. Suddenly, he saw a patch of white. “Look!” he cried.

“What is it?” Pega squinted against the dark shadow of the forest.

“It’s a hare or a cat, curled up. No, it isn’t! It’s a face!” Jack began sliding down the steep sides of the rock.

“Wait for me,” gasped Pega, sliding and tumbling after him. “It’s a person! Someone sleeping in the forest, only he’s covered with moss. Oh, it’s terrible!”

Jack saw signs of a struggle, slash marks and turf pried up. Whoever it was had not gone down peacefully. He got to the site, pulled back a tangle of vines that were stealthily covering the moss, and shouted, so great was his shock.

“Thorgil! Oh, my dear! Thorgil! Wake up! I’ll save you!” Her body was completely engulfed, but her face and throat were still clear. Jack tried to pull the moss up with his hands. It was thicker and stronger than any such plant he’d ever encountered. His fingers made no more impression on it than if he’d been trying to claw up stone.

“I can’t find anything to dig with,” moaned Pega, pulling at roots and yanking at the branches of a tree. “These are like iron! I can’t break them!”

“I can try magic,” Jack said, “but it might be dangerous. Stand back, Pega. I’m not sure what will happen.” Pega retreated to the edge of the rock. Jack rested his staff on the moss and tried to calm his mind.

What do I ask for? What do I say?he thought desperately. He was afraid to call fire. It might burst out and incinerate all of them. Even as he considered, he saw the moss creep softly up Thorgil’s throat– and recoil.

It curled back, and flakes of ash drifted off in the slight breeze. The shield maiden’s eyes were closed and her face was very pale, but the moss stirred gently over her chest. She was still breathing. Some power lay between her and the forest.

The rune of protection,thought Jack. He couldn’t see it—it was invisible except for that brief time when it was passed from one person to another—but he felt its presence. The Bard had worn it when he passed through the Valley of Lunatics. Jack had carried it in Jotunheim and had given it up only to keep Thorgil from killing herself. It was pure life force.

Jack yearned to touch it. He didn’t dare. The rune could only be given freely. It burned whoever tried to take it by force, as it was burning the moss now and keeping it from covering Thorgil’s face.

He racked his brains for a solution. He knew how to call up fog and wind, find water, kindle fire, and (once) cause an earthquake. None of these would do him any good now. If only I could wake her,thought Jack. She could will new strength from the rune.He stroked her forehead and called her name, but she slept on.

“Can I help?” said Pega from the rock.

“You don’t know magic,” Jack said impatiently. He didn’t want to be interrupted.

“I could sing.”

Jack’s head snapped up. Sing! Of course! What was the one thing most likely to rouse Thorgil to action? Without bothering to explain, he began:

Cattle die and kin die.

Houses burn to the ground.

But one thing never perishes:

The fame of a brave warrior.

“That’s an odd thing to tell someone who might be dying,” Pega said.

“Be quiet,” said Jack. He went on:

Ships go down in the sea.

Kingdoms turn into dust.

One thing outlasts them all:

The fame of a brave warrior.

Fame never dies!

Fame never dies!

Fame never dies!

As he sang, the memory of the Northmen came back to him. They were in Olaf One-Brow’s ship with a wind filling the red-and-cream-striped sail. Their lives were violent, they were thugs of the worst kind, foul, half crazy, and stupid, and yet… they were noble as well.

Jack began the song again, and Pega joined in—she was a quick study for music. “Fame never dies! Fame never dies! Fame never dies!”Thorgil’s face lost its deathly pallor, and her lips trembled as though she was trying to join in. Her eyes flew open.

“Jack?” she whispered.

“You’ve got to live,” Jack said, so delighted that he could hardly contain himself. Her eyes lost their brightness and began to close. “What kind of oath-breaking coward are you!” he shouted. “Is this an honorable death? Sleeping on a soft bed like the lowest thrall? Faugh! You deserve to go to Hel!”

“Jack!” cried Pega, shocked.

“Be still. I know what I’m doing. Thorgil Chicken-Heart is what they’ll call you,” he told the shield maiden. “Thorgil Brj’stabarn! Suckling baby!”

“I am nota brj’stabarn,” snarled Thorgil, her face flushing red and her body quivering under the moss.

“Then live, you sorry excuse for carrion!”

The shield maiden’s mouth contorted as though she had so many vile curses to utter, she couldn’t get them out fast enough. The moss on her chest began to turn brown and flake away. The line of destruction moved down her arms and legs. She wrenched herself up and felt for her knife. Then weakness overtook her, and she collapsed to her knees, shaking violently.

“That’s better,” Jack said.

“Let me help you,” Pega cried, bounding to Thorgil’s side.

“No one…”—the shield maiden stopped and panted, so great was her exhaustion—“needs… to help me.”

“Look at you. You can’t even talk straight. ’Course you need help.” Pega attempted to lift her, but Thorgil gave her a feeble slap.

“Leave her alone,” Jack said. “Thorgil Brj’stabarncan crawl if she can’t walk.”

“Hate… you,” said Thorgil, breathing heavily.

Jack went back to sit on the rocks. He felt as light as a sunbeam. “I’d get off that moss if I were you. Your choice, of course.” Pega looked up at him in consternation. “I know you think I’m horrible, Pega, but I learned my manners from Northmen. They can hardly get through the day without ten insults and at least one death threat.” Pega, after getting slapped—weakly—a few times, retreated to the rocks to sit by Jack.

Together they watched the shield maiden drag herself forward on hands and knees. Jack’s heart, in spite of his harsh words, ached to see her struggle, but he also knew it was useless to interfere. Thorgil would have to rescue herself. Otherwise, she would feel humiliated and be even harder to deal with. Finally, she crept onto the lowest layer of stone, beyond the reach of questing tree roots.