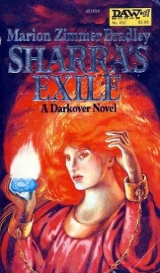

Текст книги "Sharra's Exile"

Автор книги: Marion Zimmer Bradley

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 27 страниц)

Merryl went, but he no longer looked quite so much like a puppy that had been kicked. Regis, acutely uncomfortable, followed Dyan through the street. The Comyn lord turned into the doorway of what looked like a small, discreet tavern. Inside, he recognized the place for what it was, but Dyan shrugged and said, “We’ll meet no other Comyn here, and I can endure to be spared the company of any more like the last!” The flicker of unspoken thought again, if you value your privacy, lad, you might as well get used to places like this one, was so indifferent that Regis could ignore it if he chose.

“As you wish, kinsman.”

“The food’s quite good,” Dyan said, “and I have ordered dinner. You needn’t see anything else of the place, if you prefer not to.” He followed a bowing servant into a room hung with crimson and gilt, and talked commonplaces—about the decorations, about the soft stringed music playing—while young waiters came and brought all kinds of food.

“The music is from the hills; they are a famous group of four brothers,” said Dyan. “I heard them while they were still in Nevarsin, and it was I who urged them to come to Thendara.”

“A beautiful voice,” said Regis, listening to the clear treble of the youngest musician.

“Mine was better, once,” said Dyan, and Regis, hearing the indifference of the voice, knew it covered grief. “There are many things you do not know about me; that is one. I have done no singing since my voice broke, though when I was in the monastery for a time last winter, I sang a little with the choir. It was peaceful in the monastery, though I am not a cristoforoand will never be so; their religion is too narrow for me. I hope a day will come when you will find it so, Danilo.”

“I am not a good cristoforo,” Danilo said, “but it was my father’s faith and will be mine, I suppose, till I find a better.”

Dyan smiled. He said, “Religion is an entertainment for idle minds, and yours is not idle enough for that. But it does a man in public life no harm to conform a little to the religion of the people, if the conformity is on the surface and does not contaminate his serious thinking. I hold with those who say, even in Nevarsin, There is no religion higher than the truth. And that is not blasphemy either, foster-son; I heard it from the lips of the Father Master. But enough of this—I had something to say to you, Danilo, and I thought to save you the trouble of running at once to pour it into Regis’s ears. In a word; I am a man of impulse, as you have known for a long time. Last year I dwelt for a time at Aillard, and Merryl’s twin sister bore me a son ten days since. Among other business of the Comyn, I am here to have him legitimated.”

Danilo said correctly, “My congratulations, foster-father.”

Regis said a polite phrase also, but he was puzzled.

“You are surprised, Regis? I am a bit surprised myself. In general, even for diversion, I am no lover of women—but as I say, I am… a creature of impulse. Marilla Lindir is not a fool; the Aillard women are cleverer than the men, as I have reason to know. I think it pleased her to give Ardais a son, since sons to Aillard have no chance of inheriting that Domain. I suppose you know how these things can happen—or are you both too young for that?” he asked with a lift of the eyebrows, and a touch of malice. “Well, so it went—when I found she was pregnant, I said nothing. It might have been a daughter for Aillard, rather than an Ardais son—but I took the trouble to have her monitored and to be sure the child was mine. I did not speak of it when we met at Midwinter, Danilo, because anything might have befallen; even though I knew she bore a son, she might have miscarried, the child might have been stillborn or defective—the Lindirs have Elhalyn blood. But he is healthy and well.”

“Congratulations again, then,” said Danilo.

“Do not think this will change anything for you,” said Dyan. “The lives of children are—uncertain. If he should come to misfortune before he is grown, nothing will change; and should I die before he is come to manhood, I should hope you will be married by then and be named Regent for him. Even so, when he leaves his mother’s care, I am no man to raise a child, nor would I care, at my age, to undertake it; I should prefer it if you would foster him. I will soon apply myself to finding you a suitable marriage—Linnell Lindir-Aillard is pledged to Prince Derik, but there are other Lindirs, and there is Diotima Ridenow, who is fifteen or sixteen now, and—well, there is time enough to decide; I do not suppose you are in any too great a hurry to be wedded,” he added ironically.

“You know I am not, foster-father.”

Dyan shrugged. “Then any girl will do, since I have saved you the trouble of providing an Heir to Ardais; we can choose one who is amiable, and content to keep your house and run your estate,” he said. “A legal fiction, if you wish.” He turned his eyes to Regis, and added, “And while I am about it, my congratulations are due to you, too; your grandfather told me about the Di Asturien girl, and your son—will he be born this tenday, do you suppose? Is there a marriage in the offing?”

Shock and anger flooded through Regis. He had intended to tell Danilo this in his own time. He said stiffly, “I have no intention of marrying at this time, kinsman. No more than you.”

Dyan’s eyes glinted with amused malice. He said, “Why, have I said the wrong thing? I’ll leave you to make your peace with my foster-son, then, Regis.” He rose and bowed to them with great courtesy. “Pray command anything here you wish, wine or food or—entertainment; you are my guests this evening.” He bowed again and left them, taking up his great fur-lined cloak, which flowed behind him over his arm like a living thing.

After a minute Danilo said, and his voice sounded numb, “Don’t mind, Regis. He envies our friendship, no more than that, and he is striking out. And, I suppose, he feels foolish; to father a bastard son at his age.”

“I swear I meant to tell you,” Regis said miserably, “I was waiting for the right time. I wanted to tell you before you heard it somewhere as gossip.”

“Why, Regis, what is it to do with me, if you have love affairs with women?”

“You know the answer to that,” said Regis, low and savage, “I have no love affairswith women. You know that things like this must happen, while I am Heir to Hastur. Comyn Heirs at stud in the Domains—that’s what it amounts to! Dyan doesn’t like it any better than you do, but even so, he spoke of getting you married off. And I am damned if I’ll marry someone they choose for me, as if I were a stud horse! That’s what it was, and that is allit was. Crystal di Asturien is a very nice young woman; I danced with her at half a dozen of the public dances, I found her friendly and pleasant to talk to, and—” He shrugged. “What can I say to you? She wanted to bear a Hastur son. She’s not the only one. Do I have to apologize for what I must do, or would you rather I did not enjoy it?”

“You certainly owe me no apologies.” Danilo’s voice was cold and dead.

“Dani—” Regis pleaded, “are we going to let Dyan’s malice drive a wedge between us, after all this time?”

Danilo’s face softened. “Never, bredhyu. But I don’t understand. You already have an Heir—you have adopted your sister’s son.”

“And Mikhail is still my Heir,” Regis retorted, “but the Hastur heritage has hung too long on the life of a single child. My grandfather will not force me to marry—as long as I have children for the Hastur lineage. And I don’t want to marry,” he added. The unspoken awareness hung in the air between them.

A waiter came, bowing, and asked if the vai domynhad any other pleasure: wine, sweets, young entertainers– He weighted this last heavily, and Danilo could not conceal a grimace of distaste.

“No, no, nothing more.” He hesitated, glancing at Regis. “Unless you—”

Regis said wryly, “I am a libertine only with women, Dani, but no doubt I have given you cause to think otherwise.”

“If we have to quarrel,” Dani said, with a gulp, “Let us at least do it in clean air and not in a place like this!”

Regis felt a great surge of enormous bitterness. Dyan had done this, damn it! He said, “Oh, no doubt, this is the place for lovers’ quarrels of this kind—and I suppose if the Heir to Hastur and his favorite must quarrel, better here than in Comyn Castle, where all the Domains, sooner or later, will hear!”

And again he felt, it is more of a burden than I can bear!

CHAPTER TWO

« ^ »

Vainwal: Terran Empire

Fifth year of exile

Dio Ridenow saw them first in the lobby of the luxury hotel serving humans, and humanoids, on the pleasure-world of Vainwal. They were tall, sturdy men, but it was the blaze of red hair on the elder of them that drew her eyes; Comyn red. He was past fifty and walked with a limp: his back was bent, but it was easy to see that once he had been a large and formidable man. Behind him walked a younger man in nondescript clothing, darkhaired and black-browed, sullen, with steel-gray eyes. Somehow he had the look of deformity, of suffering, which Dio had learned to associate with lifetime cripples; yet he had no visible defect except for a few ragged scars along one cheek. The scars drew up one half of his mouth into a permanent sneer, and Dio turned her eyes away with a sense of revulsion; why would a Comyn lord have such a person in his entourage?

For it was obvious that the man was a Comyn lord. There were redheads in other worlds of the Empire, and plenty on Terra itself; but there was a strong facial stamp, an ethnic likeness; Darkovan, Comyn, unmistakable. And the older man’s hair, flame-red, now dusted with gray. But what was he doing here? For that matter, who was he? It was rare to find Darkovans anywhere but on their home world. The girl smiled; someone might have asked her that question, as well, for she was Darkovan and far from home. Her brothers came here because, basically, neither of them was interested in political intrigue; but they had had to defend and justify their absence often enough.

The Comyn lord moved across the great lobby slowly limping, but with a kind of arrogance that drew all eyes; Dio framed it to herself, in an unfocused way; he moved as if he should have been preceded by his own drone-pipers, and worn high boots and a swirling cloak—not the drab, featureless Terran clothing he actually wore.

And having identified his Terran clothing, suddenly Dio knew who he was. Only one Comyn lord, as far as anyone knew, had actually married, di catenasand with full ceremony, a Terran woman. He had managed to live down the scandal, which in any case had been before Dio was born. Dio herself had not seen him more than twice in her life; but she knew that he was Kennard Lanart-Alton, Lord Armida, self-exiled Head of the Alton Domain. And now she knew who the younger man must be, the one with the sullen eyes; this would be his half-caste son Lewis, who had been horribly injured in a rebellion somewhere in the Hellers a few years ago. Dio took no special interest in such things, and in any case she had still been playing with dolls when it happened. But Lew’s foster-sister Linnell Aillard had an older sister, Callina, who was Keeper in Arilinn; and from Linnell Dio had heard about Lew’s injuries, and that Kennard had taken him to Terra in the hope that Terran medical science could help him.

The two Comyn were standing near the central computer of the main hotel desk; Kennard was giving some quietly definite order about their luggage to the human servants who were one of the luxury touches of the hotel. Dio herself had been brought up on Darkover, where human servants were commonplace and robots were not; she could accept this kind of service without embarrassment. Many people could not overcome their shyness or dismay at being waited on by people rather than servomechs or robots. Dio’s poise about such things had given her status among the other young people on Vainwal, many of them among the new-rich in an expanding Empire, who flocked to the pleasure worlds like Vainwal, knowing little of the refinements of good living, unable to accept luxury as if they had been brought up to it. Blood, Dio thought, watching Kennard and the exactly right way he spoke to the servants, would always tell.

The younger man turned; Dio could see now that one hand was kept concealed in a fold of his coat, and that he moved awkwardly, struggling one-handed to handle some piece of their equipment which he seemed not to want touched by anyone else. Kennard spoke to him in a low voice, but Dio could hear the impatient tone of the words, and the young man scowled, a black and angry scowl which made Dio shudder. Suddenly she realized that she did not want to see any more of that young man. But from where she stood she could not leave the lobby without crossing their path.

She felt like lowering her head and pretending they were not there at all. After all, one of the delights of pleasure worlds like Vainwal was to be anonymous, freed of the restraints of class or caste on one’s own home world; she would not speak to them, she would give them the privacy she wanted for herself.

But as she crossed their path, the young man, not seeing Dio, made a clumsy movement and banged full into her. Whatever he was carrying slid out of his awkward one-handed grip and fell to the floor with a metallic clatter; he muttered some angry words and stooped to retrieve it.

It was long, narrow, closely wrapped; more than anything else it looked like a pair of dueling swords, and that alone could explain his caution; such swords were often precious heirlooms, never entrusted to anyone else to handle. Dio stepped away, but the young man fumbled with his good hand and succeeded only in sending it skidding farther away across the floor. Without thinking, she bent to retrieve it and hand it to him—it was right at her feet—but he actually reached out and shoved her away from it.

“Don’t touch that!” he said. His voice was harsh; raw, with a grating quality that set her teeth on edge. She saw that the arm he had kept concealed inside his coat ended in a neatly folded empty sleeve. She stared, open-mouthed with indignation, as he repeated, with angry roughness, “Don’t touch that!”

She had only been trying to help!

“Lewis!” Kennard’s voice was sharp with reproof; the young man scowled and muttered something like an apology, turning away and scrambled the dueling swords, or whatever the untouchable package was, into his arms, turning ungraciously to conceal the empty sleeve. Suddenly Dio felt herself shudder, a deep thing that went all the way to the bone. But why should it affect her so? She had seen wounded men before this, even deformed men; surely a lost hand was hardly reason to go about as this one did, with an outraged, defensive scowl, a black refusal to meet the eyes of another human being.

With a small shrug she turned away; there was no reason to waste thought or courtesy on this graceless fellow whose manners were as ugly as his face! But, turning, she came face to face with Kennard.

“But surely you are a countrywoman, vai domna? I did not know there were other Darkovans on Vainwal.”

She dropped him a curtsy. “I am Diotima Ridenow of Serrais, my lord, and I am here with my brothers Lerrys and Geremy.”

“And Lord Edric?”

“The Lord of Serrais is at home on Darkover, sir, but we are here by his leave.”

“I had believed you destined for the Tower, mistress Dio.”

She shook her head and knew the swift color was rising in her face. “It was so ordained when I was a child; I—I was invited to take service at Neskaya or Arilinn. But I chose otherwise.”

“Well, well, it is not a vocation for everyone,” said Kennard genially, and she contrasted the charm of the father with the sneering silence of the son, who stood scowling without speaking even the most elementary formal phrases of courtesy! Was it his Terran blood which robbed him of any vestige of his father’s charm? No, for good manners could be learned, even by a Terran. In the name of the blessed Cassilda, couldn’t he even lookat her? She knew that it was only the scar tissue pulling at the corner of his mouth which had drawn his face into a permanent sneer, but he seemed to have taken it into his very soul.

“So Lerrys and Geremy are here? I remember Lerrys well from the Guards,” Kennard said. “Are they in the hotel?”

“We have a suite on the ninetieth floor,” Dio said, “but they are in the amphitheater, watching a contest in gravity-dancing. Lerrys is an amateur of the sport, and reached the semi-finals; but he tore a muscle in his knee and the medics would not permit him to continue.”

Kennard bowed. “Convey them both my compliments,” he said, “and my invitation, lady, for all three of you to be my guests tomorrow night, when the finalists perform here.”

“I am sure they will be charmed,” Dio said, and took her leave.

She heard the rest of the story that evening from her brothers.

“Lew? That was the traitor,” said Geremy, “Went to Aldaran as his father’s envoy and sold Kennard out, to join in some kind of rebellion among those pirates and bandits there. His mother’s people, after all.”

“I had thought Kennard’s wife was Terran,” Dio said.

“Half Terran; her mother’s people were Aldarans,” Geremy said. “And believe me, Aldaran blood isn’t to be trusted.”

Dio knew that; the Domain of Aldaran had been separated from the original Seven Domains, so many generations ago that Dio did not even know how long it had been, and Aldaran treachery was proverbial. She said, “What were they doing?”

“God knows,” Geremy said. “They tried to hush it up afterward. It seems they had some kind of super-matrix back there, perhaps stolen from the forge-folk; I never heard it all, but it seems Aldaran was experimenting with it, and dragged Lew into it—he’d been trained at Arilinn, after all, old Kennard gave him every advantage. We knew no good would come of it; burned down half of Caer Donn when the thing got out of hand. After that, I heard Lew switched sides again and sold out Aldaran the way he sold us out; joined up with one of those hill-woman bitches, one of Aldaran’s bastard daughters, half-Terran or something, and got his hand burned off. Served him right, too. But I guess Kennard couldn’t admit what a mistake he’d made, after all he’d gone through to get Lew declared his Heir. I wonder if they managed to regenerate his hand?” He wiggled three fingers, lost in a duel years ago and regenerated good as new by Terran medicine. “No? Maybe old Kennard thought he ought to have something to remember his treachery by.”

“No,” Lerrys said. “You have it wrong way round, Geremy. Lew’s not a bad chap; I served with him in the Guards. He did his damnedest, I heard, to control the fire-image when it got out of hand but the girl died. I heard he’d married her, or something. I heard from one of the monitors of Arilinn, how hard they’d worked to save her. But the girl was just too far gone, and Lew’s hand—” He shrugged. “They said he was lucky to have gotten off that easy. Zandru’s hells, what a thing to have to face! He was one of the most powerful telepaths they ever had at Arilinn, I heard; but I knew him best in the Guards. Quiet fellow, standoffish if anything, nice enough when you got to know him; but he wasn’t easy to know. He had to put up with a lot of trouble from people who thought he had no right to be there, and I think it warped him. I liked him, or would have if he’d let me; he was touchy as the devil, and if you were halfway civil to him, he’d think he was being patronized, and get his back up.” Lerrys laughed soundlessly.

“He was so standoffish with women that I made the mistake of thinking he was—shall we say—one who shared my own inclinations, and I made him a certain proposition. Oh, he didn’t saymuch, but I never asked him thatagain!” Lerrys chuckled. “Just the same, I’ll bet he didn’t have a good word for you, either? That’s a new thing for you, isn’t it, little sister, to meet a man who’s not at your feet within a few minutes?” Teasing, he chucked her under the chin.

Dio said, pettishly, “I don’t like him; he’s rude. I hope he stays far away from me!”

“I suppose you could do worse,” Geremy mused. “He isHeir to Alton, after all; and Kennard isn’t young, he married late. He may not be long for this world. Edric would like it well if you were to be Lady of Alton, sister.”

“No.” Lerrys put a protecting arm around Dio. “We can do better than that for our sister. Council will never accept Lew again, not after that business with Sharra. They never accepted Kennard’s other son, in spite of the best Ken could do; and Marius’s worth two of Lew. Once Kennard’s gone, they’ll look elsewhere for a Head of the Alton Domain—there are claimants enough! No, Dio—” gently he turned her around to look at him—“I know there aren’t many young men of your own kind here, and Lew’s Darkovan, and, I suppose, handsome, as women think of these things. But stay away from him. Be polite, but keep your distance. I like him, in a way, but he’s trouble.”

“You needn’t worry about that,” Dio said. “I can’t stand the sight of the man.”

Yet inside, where it hurt, she felt a pained wonder. She thought of the unknown girl Lew had married, who had died to save them all from the menace of the fire-Goddess. So it had been Lew who raised those fires, then risked death and mutilation to quench them again? She felt herself shivering again in dread. What must his memories be like, what nightmares must he live, night and day? Perhaps it was no wonder that he walked apart, scowling, and had no kind word or smile for man or woman.

Around the ring of the null-gravity field, small crystalline tables were suspended in midair, their seats apparently hanging from jeweled chains of stars. Actually they were all surrounded by energy-nets, so that even if a diner fell out of his chair (and where the wine and spirits flowed so freely, some of them did), he would not fall; but the illusion was breathtaking, bringing a momentary look of wonder and interest even to Lew Alton’s closed face.

Kennard was a generous and gracious host; he had commanded seats at the very edge of the gravity ring, and sent for the finest of wines and delicacies; they sat suspended over the starry gulf, watching the gravity-free dancers whirling and spinning across the void below them, soaring like birds in free flight. Dio sat at Kennard’s right hand, across from Lew, who, after that first flash of reaction to the illusion of far space, sat motionless, his scarred and frowning face oblivious. Past them, galaxies flamed and flowed, and the dancers, half-naked in spangles and loose veils, flew on the star-streams, soaring like exotic birds. His right hand, evidently artificial and almost motionless, lay on the table unstirring, encased in a black glove. That unmoving hand made Dio uncomfortable; the empty sleeve had seemed, somehow, more honest.

Only Lerrys was really at ease, greeting Lew with a touch of real cordiality; but Lew replied only in monosyllables, and Lerrys finally tired of trying to force conversation and bent over the gulf of dancers, studying the finalists with unfeigned envy, speaking only to comment on the skills, or lack of them, in each performer. Dio knew he longed to be among them.

When the winners had been chosen and the prizes awarded, the gravity was turned on, and the tables drifted, in gentle spiral orbits, down to the floor. Music began to play, and dancers moved onto the ballroom surface, glittering and transparent as if they danced on the same gulf of space where the gravity-dancers had whirled in free-soaring flight. Lew murmured something about leaving, and actually half-rose, but Kennard called for more drinks, and under the service Dio heard him sharply reprimanding Lew in an undertone; all she heard was “Damn it, can’t hide forever—”

Lerrys rose and slipped away; a little later they saw him moving onto the dance floor with an exquisite woman whom they recognized as one of the performers, in starry blue covered now with drifts of silver gauze.

“How well he dances,” Kennard said genially. “A pity he had to withdraw from the competition. Although it hardly seems fitting for the dignity of a Comyn lord—”

“Comyn means nothing here,” laughed Geremy, “and that is why we come here, to do things unbefitting the dignity of Comyn on our own world! Come, kinsman, wasn’t that why youcame here, to be free for adventures which might be unseemly or worse in the Domains?”

Dio was watching the dancers, envious. Perhaps Lerrys would come back and dance with her. But she saw that the woman performer, perhaps recognizing him as the contestant who had had to withdraw, had carried him off to talk to the other finalists. Now Lerrys was talking intimately with a young, handsome lad, his red head bent close to the boy. The dancer was clad only in nets of gilt thread, and the barest possible gilt patches for decency; his hair was dyed a striking blue. It was doubtful, now, that Lerrys remembered that there were such creatures as women in existence, far less sisters.

Kennard watched the direction of her glance. “I can see you are longing to be among the dancers, Lady Dio, and it is small pleasure to a young maiden to dance with her brothers, as I have heard my foster-sister and now my foster-daughters complain. I have not been able to dance for many years, damisela, or I would give myself the pleasure of dancing with you. But you are too young to dance in such a public place as this, except with kinsmen—”

Dio tossed her head, her fair curls flying. She said, “I do as I please, Lord Alton, here on Vainwal, and dance with anyone I wish!” Then, seized by some imp of boredom or mischief, she turned to the scowling Lew. “Yet here sits a kinsman—will you dance with me, cousin?”

He raised his head and glared at her, and Dio quailed; she wished she had not started this. This was no one to flirt with, to exchange light pleasantries with! He gave her a murderous glance, but even so, he was shoving back his chair.

“I can see that my father wishes it, damisela. Will you honor me?” The harsh voice was amiable enough—if you did not see the look deep in his eyes. He held out his good arm to her. “You will have to forgive me if I step on your feet. I have not danced in many years. It is not a skill much valued on Terra, and my years there were not spent where dancing was common.”

Damn him, Dio thought, this was arrogance; he was not the only crippled man in the universe, or on the planet, or even in this room—his own father was so lame he could hardly put one foot before the other, and made no bones about saying so!

He did not step on her feet, however; he moved as lightly as a drift of wind and after a very little time, Dio gave herself up to the music, and the pure enjoyment of the dance. They were well matched, and after a few minutes of moving together in the perfect rhythm—she knew she was dancing with a Darkovan, nowhere else in the civilized Empire did any people place so much emphasis on dancing as on Darkover—Dio raised her eyes and smiled at him, lowering mental barriers in a way which any Comyn would have recognized as an invitation for the telepathic touch of their caste.

For the barest instant, his eyes met hers and she felt him reach out to her, as if by instinct, attuned to the sympathy between their bodies. Then, without warning, he slammed the barrier down between them, hard, leaving her breathless with the shock of it. It took all her self-control not to cry out with the pain of that rebuff, but she would not give him the satisfaction of knowing that he hurt her; she simply smiled and went on enjoying the dance at an ordinary level, the movement, the sense of being perfectly in tune with his steps.

But inside she felt dazed and bewildered. What had she done to merit such a brutal rejection? Nothing, certainly; her gesture had indeed been bold, but not indecently so. He was, after all, a man of her own caste, a telepath and a kinsman, and if he felt unwilling to accept the offered intimacy, there were gentler ways of refusing or withdrawing.

Well, since she had done nothing to deserve it, the rebuff must have been in response to his own inner turmoil, and had nothing to do with her at all. So she went on smiling, and when the dance slowed to a more romantic movement, and the dancers around them were moving closer, cheek against cheek, almost embracing, she moved instinctively toward him. For an instant he was rigid, unmoving, and she wondered if he would reject the physical touch, too; but after an instant his arm tightened round her. Through the very touch, though his mental defenses were locked tight, she sensed the starved hunger in him– How long had it been, she wondered, since he had touched a woman in any way? Far too long, she was sure of that. The telepath Comyn, particularly the Alton and Ridenow, were well-known for their fastidiousness in such matters; they were hypersensitive, much too aware of the random or casual touch. Not many of the Comyn were capable of tolerating casual love affairs.

There were exceptions, of course, Dio thought; the young Heir to Hastur had the name of a follower of women; though he was likely to seek out musicians or matrix mechanics, women who were sensitive and capable of sharing emotional intensity, not common women of the town. Her brother Lerrys, too, was promiscuous in his own way, though he too tended to seek out those who shared his own consuming interests– A quick glance told her that he was dancing with the youngster in the gilded nets, a quick-flaring, overflowing intimacy of shared delight in the dance.

The dance slowed, the lights dimming, and she sensed that all around them couples were moving into each other’s arms. A miasma of sensuality, almost visible, seemed to lie like mist over the whole room. Lew held her tight against him, bending his head; she raised her face, again gently inviting the touch he had rebuffed. He did not lower his mental barriers, but their lips touched; Dio felt a slow, drowsy excitement climbing in her as they kissed. When they drew apart his lips smiled, but there was still a great sadness in his eyes.