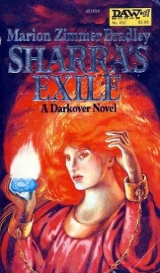

Текст книги "Sharra's Exile"

Автор книги: Marion Zimmer Bradley

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 24 (всего у книги 27 страниц)

CHAPTER TWO

« ^ »

Lew Alton’s narrative

The sullen red of another day was dying when I woke; my head throbbed with the half-healed wound Kadarin had given me, and my arm was afire with the long slash from Regis’s dagger. I lay and wondered for a moment if the whole thing had been a delirious nightmare born of concussion. Then Andres came in, and the deep lines of grief in his face told me it was real. He had loved Linnell, too. He came and scowled at me, taking off the bandage on my head and inspecting the stitches, then looked at the wound in the arm.

“I suppose you are the only man on Darkover who can go to a Festival Night ball and come home with something like this,” he grumbled. “What sort of fight was it?”

So he had heard only that Linnell was dead—not of the monstrous visitation of Sharra. The cut hurt, but it was no more than a flesh wound. I’d have trouble using the arm for a while, but I held no resentment; Regis had done the only thing he could, releasing me from the call of Sharra. I said, “It was an accident, he didn’t mean to hurt me,” and let him think what he liked. “Get me something to eat and some clothes. I have to find out what’s happening—”

“You look as if you needed a tenday in bed,” Andres said crossly. Then his very real concern for me surfaced in a harsh, “Lad, I’ve lost two of you! Don’t send yourself after Marius and Linnell! What’s going on that you can’t wait until tomorrow for it?”

I yielded and lay quiet. Somewhere out there Sharra raged, I supposed… but I would know if they came into the Comyn Castle (was I altogether freed? I did not dare look at my matrix to see) and there was nothing to be gained by going out and looking for trouble. I watched Andres grumbling around the room, a soothing sound I remembered from boyhood. When Marius or I had raced our horses at too breakneck a pace and tumbled off, breaking a finger or a collarbone on the way down, he had grumbled in exactly the same way.

Marius and I had never had the boyhood squabbles and fistfights of most brothers I knew; there had been too many years between us. By the time he was out of pinafores and able to assert himself, I was already grown and into the cadet corps. I had only begun to know what kind of man my brother was, and then he was gone from me, the furthest distance of all. I had dragged him, too, into the inexorable fates pursuing me. But at least he had had a clean death, a bullet through the brain, not the death in fire that waited for me.

For now that Kadarin was loose with the Sharra sword, I knew how I would die, and made up my mind to it. Ashara’s plan, and the help of Regis Hastur’s new and astonishing Gift, which seemed somehow to hold power over Sharra, might destroy the Sharra matrix; but I knew perfectly well that I would go with it into destruction.

Well, that was what had awaited me for all these years, bringing me back to Darkover at the appointed time, to the death appointed, which I should have shared with Marjorie.

We had planned our death…I remembered that morning in Castle Aldaran when, hostages to the destruction Sharra was sowing in the country round, showering on the Terran spaceport in Caer Donn, I had been allowed to waken from the drugs that had kept me, passive prisoner, chained to the destruction and feeding power into Sharra. I never knew why I had been allowed to come free of the drugs; certainly it had not been any lingering tenderness on Kadarin’s part for either of us. But Marjorie and I had been prepared to die… knew we must die in closing the gateway into this world that was Sharra. And so she and I, together, had smashed the gateway…

But then I, using all the power of that matrix, had taken her, and the Sword, and flung us through space bodily—the Terrans called it teleportation, and I had never done it before or since—to Arilinn; where Marjorie had died from her terrible burns, and I…

… I had survived, or some part of me had survived, and all these years had despised myself because I had not followed her to death. Now I knew why I had been spared: Kadarin and Thyra still lived, and somehow they would have recovered the matrix and ravaged Darkover again with its fire. This time there would be no respite; and when Sharra was destroyed, none of us would be left alive. And so I must set my affairs in order.

I called Andres back to me, and said, “Where is the little girl?”

“Rella—that’s the cook’s helper—looked after her today, and put her to bed in the room Marius had when he was a little tyke,” Andres said.

“If I live, I may be able to take her to Armida,” I said, “but if anything should happen to me—no, foster-father, listen; nothing’s certain in this life. Now that my father and brother are gone—you have served us all faithfully for a quarter of a century. If something should happen to me, would you leave Darkover?”

“I don’t know. I never thought about it,” the old man said. “I came here with DomKennard when we were young men, and it’s been a good life; but I think I might go back to Terra in the end.” He added, with a mirthless grin, “I’ve wondered what it would be like, to be under my own blue sky again, and have a moon like a moon ought to be, not those little things.” He pointed out the window at the paling face of Idriel, greenish like a gem through water.

“Bring me something to write on.” When he complied, I scribbled with my good hand, folded the paper and sealed it.

“I can’t leave Armida to you,” I said. “I suppose Gabriel will have it after me; it’s in the Alton Domain. I would if I could, believe me. But if you take this to the Terran Legate in the Trade City, this will take you to Terra, and I’d rather you would foster Marja yourself than turn her over to Gabriel’s wife.” DomnaJavanne Hastur has never liked me; no doubt she would do her best by Gabriel’s kinsman, but it would be a cold and dutiful best; and Andres, at least, would care for my daughter for my father’s sake and Linnell’s if not for mine. “My mother—and my father after her—owned some land there; it had better go to you, then.”

He blinked and I saw tears filling his eyes, but all he said was, “God forbid I should ever have to use it, vai dom. But I’ll do my best for the little girl if anything happens. You know I’d guard her with my life.”

I said soberly, “You might have to.” I did not know why, but I was filled suddenly with icy shivers; my blood ran cold in my veins, and for a moment, even in the dying light which turned the whole room crimson, it seemed that blood lay over the stones around me. Is this then the place of my death? Only a moment, and it was gone. Andres went to the window, drew the curtains with a bang.

“The bloody sun!” he said, and it sounded like a curse. Then he tucked the paper I had given him, without looking at it, into a pocket, and went away.

That was settled. Now there was only Sharra to face. Well, it must come when it would. Tomorrow Katie and I would ride to Hali, and the plan I had made, for finding the Sword of Aldones and using this last weapon against Sharra, would either succeed or it would fail. Either way, I would probably not see another sunset. My head was afire with the stitches in my forehead. Scars to match those Kadarin had made on my face… well, there’s an old saying that the dead in heaven is too happy to care what happens to his corpse, be it beautiful or ugly, and the dead in hell has too much else to worry about! As for me, I had never believed in either heaven or hell; death was no more than endless nothingness and darkness.

Yet it seemed I could hear again my father’s last cry, directly to my mind– Return to Darkover and fight for your rights and your brother’s! This is my last command… and then, past that, as the life was leaving him, that last cry of joy and tenderness:

Yllana! Beloved—!

Had he, at the last moment, seen something beyond this life, had my half-remembered mother been waiting for him at that last gateway? The cristoforosbelieve something like that, I know; Marjorie had believed. Would Marjorie be waiting for me beyond Sharra’s fire? I could not, dared not, let myself think so. And if it were so—I let myself smile, a sour little smile—what would we do when Dio turned up there? But she had already loosed her claim on me… if love were the criterion, perhaps she would seek Lerrys beyond the gates of death. And what of those husbands or wives given in marriage who hated their spouses, married out of duty or family ties or political expediency, so that married life was a kind of hell and death a merciful release, would any sane or just God demand that they be tied together in some endless afterlife as well? I dismissed all this as mad rubbish and tried, through the fierce pain in my head and the fiery throbbing of my wounded arm, to compose myself for sleep.

The last red light dimmed, faded and was gone. A chink of the curtains showed me pallid greenish moonlight, lying like ice across my bed; it looked cool, it would cool my fever… there was a step and a rustle and soft whisper.

“Lew, are you asleep?”

“Who’s there?”

The dim light picked out a gleam of fair hair, and Dio, her face as pale as the pallid moon, looked down at me. She turned and pulled the curtains open where Andres had closed them, letting the moonlight flood the room and the waning moons peep over her shoulder.

The chill of the moonlight seemed to cool my feverish face. I even wondered, incuriously, if I had fallen asleep and was dreaming she was there, she seemed so quiet, so muted. Her eyes were swollen and flushed with tears.

“Lew, your face is so hot…” she murmured, and after a minute she came and laid something cold and refreshing on my brow. “Do you mean they left you alone here like this?”

“I’m all right,” I said. “Dio, what’s happened?”

“Lerrys is gone,” she whispered, “gone to the Terrans, he has taken ship and swears he will never return… he tried to get me to come with him, he… he tried to force me, but this time I would not go… he said it was death to stay here, with the things that were coming for the Comyn…”

“You should have gone with him,” I said dully. I could not protect Dio now, nor care for her, with Sharra raging and Kadarin prowling like a wild beast, Thyra at his side, ready to drag me back into that same corner of hell…

“I will not go when others must stay and fight,” she said. “I am not such a coward as that…” but she was weeping. “If he truly feels we are a part of the Empire, he should have stayed and fought for that…”

“Lerrys was never a fighter,” I said. Well, neither was I, but I had been given no choice; my life was already forfeit. But I had no comfort for Dio now. I said softly, “It is not your fight, either, Dio. You have not been dragged into this thing. You could make a life for yourself elsewhere. It’s not too late.”

Lerrys was one of the hypersensitive Ridenow; the Ridenow Gift had been bred into the Comyn, to sense these other-dimension horrors in the Ages of Chaos; a Gift obsolete now, when the Comyn no longer ranged through space and time as legend said they had done in the heyday of the Towers. As those who fight forest-fire keep cagebirds to tell when the poison gases and smoke are growing too dangerous for living things—because the cagebird will die of the poisons before men are aware of them—so the Ridenow served to warn Comyn less sensitive than they of the presence of forces no man could tolerate. I was not surprised that he had fled from Darkover now…

I only wished I could do the same!

“Dio, you shouldn’t be here, at this hour—”

“Do you think I care about that?” she said, and her voice was thick with tears. “Don’t send me away, Lew. I don’t—I don’t—I won’t ask anything of you, but let me stay here with you for tonight—”

She lay beside me, her curly head against my shoulder, and I tasted salt when I kissed her. And suddenly I realized that if I had changed, Dio had changed no less. The tragedy of that thing in the hospital, which should have been our son, was her tragedy too; more hers than mine, for she had borne it in her body for months; yet I had been distraught with my own selfish grief, and left no room for her. She had come into my life when I had thought it was over forever, and given me a year of happiness, and I owed it to her to remember the happiness, not the horror and tragedy at the end.

I whispered, holding her close, “I wish it had been different. I wish I had had—more for you.”

She kissed my scarred cheek, with a tenderness which somehow drew us closer than the wildest passion. “Never mind, Lew,” she said softly into the darkness, “I know. Sleep, my love, you’re weary and wounded.”

And after a moment I felt that she was fast asleep in my arms; but I lay there, wakeful, my eyes burning with regret. I had loved Marjorie with the first fire of an untried boy, all flame and desire; we had never known what we would have grown into, for Marjorie had had no time at all. But Dio had come to me when I was a man, grown through suffering into the capacity for real love, and I had never understood, I had let her walk away from me in the first upheaval. The shared tragedy should have drawn us closer, and I had let it drive us apart.

If only I could live, I could somehow make it up to Dio, if I only had time to let her know how much I loved her…

But it is too late; I must let her go, so that she will not grieve too much for me—

But for tonight I will pretend that there is something beyond morning, that she and I and Marja can find a world somewhere, and that Sharra’s fire will burn out harmlessly before the mingling of the Sword of Aldones and the Hastur Gift…I half-knew that I was already dreaming, but I lay holding Dio sleeping in my arms until at last, near dawn, I fell asleep too.

Red sunlight woke me, and the closing of a door somewhere in the Alton suite. Dio—had she really been there? I was not sure; but the curtains she had opened to the moonlight were open to the sun, and there was a fine red-gold hair lying on my pillow. The pain in head and wounded arm had subsided to the dullest of aches; I sat up, knowing that it was time to act.

While I dressed for riding, I considered. Surely, this day or the next, what was left of the Comyn would ride to Hali for the state funeral for Linnell—and for Derik. Perhaps it would be better to ride with them, not to attract attention, and then to slip away toward the rhu fead…

No. There was no time for that. I had loved Linnell and she had been my foster-sister, but I could not wait to speak words of tenderness and regret over her grave. I could not help her now, and either way, she had gone too far to care whether or not I was there to speak at her burying. For Linnell I could only try to ensure that the land she had loved was not ravaged by Sharra’s fires. It might be that we could do something for Callina too; surely Beltran, who had been part of the original circle who had tried to raise Sharra, would die with us when we closed that gateway for the last time. And then Callina too would be freed.

I went in search of Callina, and found her in the room where I had seen Linnell playing her rryl, that night before we had gone to Ashara’s Tower. Callina was sitting before the harp, her hands lax in her lap, so white and still that I had to speak to her twice before she heard me; and then she turned a dead face to me, a face so cold and distant, so like Ashara’s, that I was shocked and horrified. I shook her, hard, and finally slapped her face; at that she came back, life and anger in her pale cheeks.

“How dare you!”

“Callina, I’m sorry—you were so far away, I couldn’t make you hear me—you were in a trance—”

“Oh, no—” she gasped, her hands flying to cover her mouth in consternation, “Oh, no, it can’t be…” she swallowed and swallowed again, fighting tears. She said, “I felt I could not bear my grief, and it seemed to me that Ashara could give me peace, take away grief… grief and guilt, because if I had not—not used the screen with you, not found that—that Kathie girl, Linnell would have been alive—”

“You don’t know that,” I said harshly. “There’s no way of telling what might have happened when Kadarin drew—that sword. Kathie might have died instead of Linnell; or they might both have died. Either way, don’t blame yourself. Where is Kathie?”

“I don’t want to see her,” Callina said shakily. “She is like—it’s like seeing Linnell’s ghost, and I cannot bear it—” and for a moment I thought she would go far away into the trance state again.

“There’s no time for that, Callina! We don’t know what Beltran, or Kadarin, may be planning,” I said. “We don’t have much time; things could start up again at any moment.” How had I been able to sleep last night, with this hanging over us? But at least now I was strong enough for what I must do. “Where is Kathie?”

At last Callina sighed and showed me the way to where Kathie slept. She was lying on a couch, awake, half naked, scanning a set of tiles, but she started as I came in, and caught a blanket around her. “Get out! Oh—it’s you again! What do you want?”

“Not what you seem to be expecting,” I said dryly. “I want you to dress and ride with us. Can you ride?”

“Yes, certainly. But why—”

I rummaged behind a panel, finding some clothes I had seen Linnell wear. It suddenly outraged me that these lengths of cloth, these embroideries, should still be intact, with Linnell’s perfume still in their folds, when my foster-sister lay cold in the chapel at the side of her dead lover. I flung them, almost angrily, across the couch.

“These will do for riding. Put them on.” I sank down to wait for her, was recalled, by her angry stare, to memory of Terran taboos. I rose, actually reddening; how could Terran women be so immodest out of doors and so prudish within? “I forgot. Call me when you’re ready.”

A peculiar choked sound made me turn back. She was staring helplessly at the armful of clothing, turning the pieces this way and that. “I haven’t the faintest notion how to get into these things.”

“After what you were just thinkingat me,” I said stiffly, “I’m certainly not going to offer to help you.”

She blushed too. “And anyway, how could I ride in a long skirt?”

“Zandru’s hells, girl, what else would you wear? They are Linnell’s riding-clothes; if she rode in them, you certainly can.” Linnell had worn them to ride to Marius’s funeral.

“I’ve never worn anything like this for riding, and I’m certainly not going to start now,” she blazed. “If you want me to ride somewhere on a horse, you’re going to have to get me some decent clothes!”

“These clothes belonged to my foster-sister; they are perfectly decent.”

“Damn it, get me some indecentones, then!”

I laughed. I had to. “I’ll see what I can do, Kathie.”

The Ridenow apartments were almost deserted this early, except for a servant mopping the stone floor, and I was glad; I had no desire to walk in upon Lord Edric. It occurred to me that Dio and I had married without the permission of her Domain Lord.

Freemate marriage cannot be dissolved after the woman has borne a child, except by mutual consent.

But that was Darkovan law. Dio and I had married by the law of the Empire… why was I thinking this, as if there were still time to go back and mend what had gone astray between us? At least I would see her once more. I asked the servant if DomnaDiotima would see me, and after a moment, Dio, in a long woolly dressing-gown, came sleepily out into the main room. Her face lighted when she saw me; but there was no time for that. I explained my predicament, and she must have read the rest in my face and manner.

“Kathie? Yes, I remember her from—from the hospital,” she said, “I still have my Terran riding things, the ones I wore on Vainwal; she should be able to wear them.” She giggled, then broke off. “I know it’s not really funny. I just can’t help it, thinking—never mind; I’ll go and help her with them.”

“And I’ll go down and see if I can find horses for us,” I said, and went down, swiftly, by an old and little-known stairway, to the Guard hall. Fortunately there was a Guardsman there who had known me when I was a cadet.

“Hjalmar, can you find horses? I must ride to Hali.”

“Certainly, sir. How many horses?”

“Three,” I said after a moment, “one with a lady’s saddle.” Kathie might ride like Dio, astride and in breeches like some Free Amazon, but Callina certainly would not. I told him where to bring them, and went back to find Kathie neatly dressed in the tunic and breeches I had seen Dio wear.

I was happy then. But I did not know it, and now it is too late– now and forever.

Some Terran poet said that– that the saddest words in any language are alwaystoo late.

The door thrust suddenly open and Regis came in. He said, “Where are you going? I’d better come with you.”

I shook my head. “No. If anything happens—if we don’t make it—you’re the only one with any strength against Sharra.”

“That is exactly why I must come with you,” Regis said. “No, leave the women here—”

“Kathie at least must come,” I said. “We are going to Hali, to the rhu fead,” and added, when he still looked confused, “It’s possible that Kathie may be the only person on this world who can reach the Sword of Aldones.”

His eyes widened. He said, “There’s something I should know… Grandfather told me once—no, I can’t remember.” His brow ridged in angry concentration. “It could be important, Lew!”

It could, indeed. The Sword of Aldones was the ultimate weapon against Sharra. And Regis seemed, of late, to have some curious power over Sharra. But whatever it was, we had no time to waste while he tried to remember.

Regis warned, “If Dyan sees you, you’ll be stopped. And Beltran has a legal right—if no other—to stop Callina. How are you going to get out of the Castle?”

I led them to the Alton rooms. The Altons, generations and generations ago, had designed this part of the castle, and they had left themselves a couple of escape routes. It occurred to me to wonder why they had guarded themselves against their fellow Comyn, in those days; then I grinned with mirth. This was certainly not the first time, in the long history of the Comyn, that powerful clan had warred against clan.

It might be the last, though.

I forced my mind away from that, searching out certain elegant designs in the parquetry flooring. My father had once shown me this escape route, but he had not troubled to teach me the pattern. I frowned, tried to sound, delicately, the matrix lock that led to the secret stairway.

Fourth level, at least! I began to wonder if I would need to hunt up my old matrix mechanic’s kit and perform the mental equivalent of picking the lock. I shifted my concentration, just a little…

… Return to Darkover… fight for your brother’s rights and your own—

My father’s voice; yet for the first time I did not resent it. In that final, unknowing rapport he had forced on me, I was sure there had been some of his memories—how else could I account for the sudden, emotional way I had reacted to Dyan? Now I stood with my toes in the proper pattern, and, not stopping to think how to do it, pushedagainst something invisible.

… to the second star, sidewise and through the labyrinth…

My mind sought out the pattern; halfway through the flickering memory that was not mine faded into nonsense, evaporated with the sting of lemon-scent in the air, but I was deeply into the pattern now and I could unravel the final twist of the lock. Beneath me the floor tilted; I jumped, scrabbled for safety as a section of the flooring moved downward on invisible machinery, revealing a hidden stair, dark and dusty, that led away downward.

“Stay close to me,” I warned, “I’ve never been down here before, though I saw it opened once.” I gestured them downward on the dusty stair; Kathie wrinkled her nose at the musty smell, and Callina held her skirts fastidiously close to her body, but they went. Regis and Dio followed us. Behind us the square of light folded itself, disappeared.

“I wish my old great-great-whatever-great grandfather had provided a light,” I fretted, “it’s as dark in here as Zandru’s—” I cut off the guard-room obscenity, substituted weakly “pockets.” I heard Dio snicker softly and knew she had been in rapport with me.

Callina said softly, “I can make light, if you need it.”

Kathie cried out in sudden fright as a green ball of pallid fire grew in Callina’s palm, spread like phosphorscence over her slender six-fingered hands. I was familiar with the over-light, but it was an uncanny sight to see, as the Keeper spread out her hands, the pallid glow leading us downward. The extended fingers broke through sticky webs, and once I fancied that gleaming little eyes followed us in the darkness, but I closed my eyes and mind to them, watching for every step under my feet. We crowded so hard on Callina’s heels that she had to warn us, in a soft, preoccupied voice, “Be careful not to touch me.” Once Kathie slipped on the strangely sticky surfaces, fell a step or two, jarringly, before I could catch and steady her. I felt with my good hand along the wall, ignoring what might be clinging there, and once the stair jogged sharply to the right, a sharp turn; without Callina’s pale light we would have stepped off into nothingness and fallen—who knows into what depths? As it was, one of us jarred a pebble loose and we heard it strike below, after a long time, very far away. We went on, and I felt my blood pounding hard in my temples. Damn it, I hoped I would never have to come down here again, I would rather face Sharra and half of Zandru’s demons!

Down, and down, and endlessly down, so that I felt half the day must be passing as we threaded the staircase and the maze into which it led; but Callina led the way, with dainty fastidious steps, as if she were treading a ballroom floor.

At last the passageway ended in a solid, heavy door. The light faded from Callina’s hands as she touched it, and I had to wrestle with the wooden bar which closed it. I could not draw it back one-handed, and Dio threw her weight against the bar; it creaked open, and light assaulted eyes dilated by the darkness of that godforgotten tunnel. I squinted through it and discovered that we were standing in the Street of Coppersmiths, exactly where I had told Hjalmar to bring the horses. At the corner of the street, through the small sound of many tiny hammers tapping on metal, there was a place where horses were shod and iron tools mended, and I saw Hjalmar standing there with the horses.

He recognized Callina, though she was folded in an ordinary thick dark cloak—I wondered if she had borrowed the coarse garment from one of her servants, or simply gone into the servants’ quarters and taken the first one she found?

“ Vai domna, let me assist you to mount…”

She ignored him, turning to me, and awkwardly, one-handed, I extended my arm to help her into the saddle. Kathie scrambled up without help, and I turned to Dio.

“Do you know where you are? How are you going to get back?”

“Not thatway,” she said fervently. “Never mind, I can find my way.” She gestured at the castle, which seemed to be very high above us on the slopes of the city; we had indeed come a long way. “I still feel I ought to come with you—”

I shook my head. I would not drag Dio into this, too. She held out her arms but I pretended not to see. I could not bear farewells, not now. I said to Regis, “See that Dio gets back safely!” and turned my back on them both. I hoisted myself awkwardly into the saddle, and rode away without looking back, forcing myself to concentrate on guiding the horse’s hoofs over the cobbled street.

Out of the Street of Coppersmiths; out through the city gates, unnoticed and unrecognized; and upward, on the road leading toward the pass. I looked down once, saw them both lying beneath me, Terran HQ and Comyn Castle, facing one another with the Old Town and the Trade City between them, like troops massed around two warring giants. I turned my back resolutely on them both, but I could not shut them away.

They were my heritage; both of them, not one alone, and try as I might, I could not see the coming battle as between Terran and Comyn, but Darkover against Darkover, strife between those who would loose ancient evil in our world in the service of Comyn, and those who would protect it from that evil.

I had allied myself with the ancient evil of Sharra. It mattered nothing that I had tried to close the gateway; it was I who had first summoned Sharra, misusing the laranwhich was my heritage, betraying Arilinn which had trained me in the use of that laran. Now I would destroy that evil, even if I destroyed myself with it.

Yet for the moment, breathing the icy wind of the high pass, the snow-laden wind that blew off the eternal glacier up there, I could forget that this might be my last ride. Kathie was shivering, and I took off my cloak and laid it over her shoulders as we rode side by side. She protested, “You’ll freeze!” but I laughed and shook my head.

“No, no—you’re not used to this climate; this is shirtsleeve weather to me!” I insisted, wrapping her in the folds. She clutched it round her, still shivering. I said, “We’ll be through the pass soon, and it’s warmer on the shores of Hali.”

The red sun stood high, near the zenith; the sky was clear and cloudless, a pale and beautiful mauve-color, a perfect day for riding. I wished that there were a hawk on my saddle, that I was riding out from Arilinn, hunting birds for my supper. I looked at Callina and she smiled back at me, sharing the thought, for she made a tiny gesture as if tossing a verrinhawk into the air. Even Kathie, with her glossy brown curls, made me think of riding with Linnell in the Kilghard Hills when we were children. Once we had ridden all the way to Edelweiss, and been soundly beaten, when we came home after dark, by my father; only now I realized that what had seemed a fearful whipping to children twelve and nine years old, had in reality been a few half-playful cuffs around the shoulders, and that father had been laughing at us, less angry than grateful that we had escaped bandits or banshee-birds. I remembered now that he had never beaten any of us seriously. Though once he threatened, when I failed to rub down and care for a horse I had ridden, leaving the animal to a half-trained stableboy, that if I neglected to see to my mounts, next time I too should have no supper and sleep on the floor in my wet riding-clothes instead of having a hot bath and a good bed waiting.