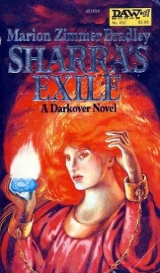

Текст книги "Sharra's Exile"

Автор книги: Marion Zimmer Bradley

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 27 страниц)

“ DomnaJavanne Lanart-Hastur and her consort, Dom Gabriel.”

Regis went to kiss his sister’s hand and draw her into the room. Javanne Hastur was a tall, handsome woman, well into her thirties now, with the strong Hastur features. She glanced at both of them and said, “Have you been quarreling with Grandfather again, Regis?” She spoke as if reproving him for climbing trees and tearing his best holiday breeches.

“Not quarreling,” he said lightly. “Simply exchanging views on the political situation.”

Gabriel Lanart grimaced and said, “That’s bad enough.”

“And I was reminding my grandson and Heir,” said Dan-van Hastur sharply, “that he is old to be unmarried, and suggesting that we might even marry him to Linnell Aillard-Lindir, if that will convince him to settle down. In Evanda’s name, Regis, what are you waiting for?”

Regis tried to control the anger surging up in him and said, “I am waiting, sir, to meet a woman with whom I can contemplate spending the rest of my life. I’m not refusing to marry—”

“I should hope not,” his grandfather snorted. “It’s—undignified for a man your age, to be still unmarried. I don’t say a word against the Syrtis youngster; he’s a good man, a suitable companion for you. But in the times that are coming, one of the things we don’t need is for anyone to name the Heir to Hastur in contempt as a lover of men!”

Regis said evenly, “And if I am, sir?”

His grandfather was denying too many unpalatable facts this evening. Now let him chew on this one. Javanne looked shocked and dismayed. Granted, it was not the right thing to say before one’s sister, but after all, Regis defended himself angrily, his grandfather knew perfectly well what the situation was.

Danvan Hastur said, “Nonsense! You’re young, that’s all. But if you’re old enough to have such pronounced views, and if I’m supposed to take them seriously, then you ought to be willing to convince me you’re mature enough to be worth hearing. I want you married, Regis, before this year is out.”

Then you will be in want for a long time, Grandfather, Regis thought, but he did not say it aloud. Javanne frowned, and he knew that she, who had somewhat more telepathic sensitivity than his grandfather, had followed the thought. She said, “Even Dyan Ardais has provided his Domain with an Heir, Regis.”

“Why, so have I,” said Regis. “Your own son, Javanne. Would it not please you if he were Hastur-lord after me? And I have other sons by other women, even though they are nedestro. I am perfectly capable of—and willing—to father sons for the Domain. But I do not want a marriage which will simply be a hoax, a sham, to please the Council. When I meet a woman I wish to marry, I wish to be free to marry her.” And as he spoke, it seemed to him that he walked side by side with someone, and the overpowering emotion that surged up in him was like nothing he had ever felt, except in the first sudden outpouring of love and gratitude when Danilo had awakened his laranand he had allowed himself to accept it, and himself. But although he knew there was a woman by his side, he could not see her face.

“You are a romantic fool,” said Javanne. “Marriage is not like that.” But she smiled and he saw the kindly look she gave Gabriel. Javanne was fortunate; she was well content in her marriage.

“When I find a woman who suits me as well as Gabriel suits you, sister, then I will marry her,” he said, and tried to keep his voice light. “And that I pledge to you. But I have not found such a woman yet, and I am not willing to marry just because it would please the Council, or you, or grandfather.”

“I don’t like hearing it said,” Javanne said, frowning, “that the Heir to Hastur is a lover of men. And if you do not marry soon, Regis, it will be said, and there will be scandal.”

“If it is said, it will be said and there’s an end to it,” Regis said, in exasperation. “I will not live my life in fear of Council tongues! There are many things that would trouble me more than Council’s speculation on my love life—which, after all, is none of their affair! I thought we came here to discuss Derik, and the other troubles we had in Council! And to have dinner—and I’ve seen no sign of food or drink! Are we to stand about wrangling over my personal affairs while the servants try to keep dinner hot, afraid to interrupt us while we are quarreling about when to hold my wedding?”

He was ready to storm out of the apartments, and his grandfather knew it. Danvan Hastur said, “Will you ask the servants to set dinner, Javanne?” As she went to do it, he beckoned a man to take Gabriel’s cloak. “You could have brought your son, Gabriel.”

Gabriel smiled and said, “He has guard duty this night, sir.”

Hastur nodded. “How does he do in the cadets, then? And Rafael, he’s in the first year, isn’t he?”

Gabriel grinned and said, “I’m trying hard not to notice Rafael, kinsman. He’s probably having the same trouble any lad of rank does in the cadets—young Gabe last year, or Regis, or Lew Alton—I still remember having to give Lew some extra skills in wrestling. They really had it in for him, they made his life miserable! I suppose Kennard himself had the same trouble when he was a first-year cadet. I didn’t, but I was out of the direct line of Comyn succession.” He sighed and said, “Too bad about Kennard. We’ll miss him. I’ll go on commanding the Guardsmen until Lew is able to make decisions—he’s really ill, and this business of Sharra hasn’t helped. But when he recovers—”

“You certainly don’t think Lew’s fit to rule the Alton Domain, do you?” Hastur asked, shocked. “You saw it as well as I did! The boy’s a wreck!”

“Hardly a boy,” Regis said. “Lew is six years older than I, which means he is halfway through his twenties. It’s only fair to wait until he’s recovered from the loss of his father, and from the journey from Vainwal. Kennard told me, once, that most long passages have to be made under heavy sedation. But when he recovers from that—”

Hastur opened his mouth to speak, but before he could say anything, Javanne said, “Dinner is on the table. Shall we go in?” and took her husband’s arm. Regis followed, with his grandfather. Dinner had been laid on a small table in the next room, with elegant cloths and the finest dishes and goblets; Javanne, at her grandfather’s nod, signaled for service and poured wine. But Gabriel said, as he spread his napkin on his knees, “Lew’s sound enough, I think.”

“He has only one hand; can he command the Guards as a cripple?”

“Precedent enough for that too,” said Gabriel. “Two or three generations ago, Dom Esteban—who was my greatgrandfather and Lew’s too, I think—commanded the Guards for ten years from a wheelchair after he lost the use of his legs in the Catmen’s War. For that matter, there was Lady Bruna, who took up her sword and made a notable commander, once, when the Heir was but a babe—” he shrugged. “Lew can dress himself and look after himself one-handed– I saw him. As for the rest—well, he was a damned good officer once. And if he wants me to go on commanding the Guards—well, he’s the head of my Domain, and I’ll do what he says. And the boys coming up—and there’s Marius. He hasn’t had military training, but he’s perfectly well-educated.”

“Terran education,” Hastur said dryly.

Regis said, “Knowledge is knowledge, Grandfather.” He remembered what he had been thinking in Council, that it made more sense to have Mikhail, perhaps, instructed under the Terrans than to shove him into the cadets for military discipline and training in swordplay. “Marius is intelligent—”

“And has some unfortunate Terran friends,” said Javanne scornfully. “If he hadn’t involved himself with the Terrans, he wouldn’t have brought out all that business about Sharra today at Council!”

“And then we wouldn’t know what was going on,” said Regis. “When a wolf is loose in the pastures, do we care if the herdsman loses a night’s sleep? And whose fault is it that Marius was not given cadet training? I’m sure he would have done as well there as I did. We chose to turn him over to the Terrans, and now, I’m afraid, we have to live with what we have made of him. We made certain that one Domain, at least, would remain allied to the Terrans!”

“The Altons have always been too ready to deal with the Terrans,” said Hastur. “Ever since the days when Andrew Carr married into that Domain—”

“Done is done,” Gabriel said, “there’s no need to hash it over now, sir. I didn’t see any signs that Lew was so happy among the Terrans that he can’t rule the Altons well—”

“You’re acting as if he were going to be Head of the Domain,” said Hastur.

Gabriel laid down his spoon, letting the soup roll out on the tablecloth. “Now look here, Grandfather. It’s one thing for me to claim the Domain when we had no notion whether Lew was alive or dead. But Council accepted him as Kennard’s Heir, and that’s all there is to it. It’s up to him, as head of the Domain, to say what’s to be done about Marius, but I suppose he’ll name him Heir. If it were Jeff Kerwin I might challenge—he doesn’t want the Domain, he wasn’t brought up to it—”

“A Terran?” asked Javanne in amazement.

“Jeff isn’t a Terran. I ought to say, DomDamon—he has no Terran blood at all. His father was Kennard’s older brother. He was fostered on Terra and brought up to think he was Terran, and he bears his Terran foster-father’s name, that’s all,” Gabriel explained, patiently, not for the first time. “He has less Terran blood than I do. My father was Domenic Ridenow-Lanart, but it was common knowledge that he was fathered by Andrew Carr. Twin sisters married Andrew Carr and Damon Ridenow—”

Danvan Hastur frowned. “That was a long time ago.”

“Funny, how a generation or two wipes out the scandal,” said Gabriel with a grin. “I thought that had all been hashed over, back when they tested Lew for the Alton Gift. He had it, I didn’t, and that was that.”

Danvan Hastur said quietly “I want you at the head of the Alton Domain, Gabriel. It is your duty to the Hastur clan.”

Gabriel picked up his spoon, frowned, rubbed it briefly on the napkin and thrust it back into his soup. He took a mouthful or two before he said, “I did my duty to the Hastur clan when I gave them two—no, three—sons, sir, and one of them to be Regis’s Heir. But I swore loyalty to Kennard, too. Do you honestly think I’m going to fight my cousin for his rightful place as Alton Heir?”

But that, Regis thought, watching the old man’s face, is exactly what Danvan Hastur does think. Or did.

“The Altons are allied to Terra,” he said. “They’ve made no secret of it. Kennard, now Lew, and even Marius, have Terran education. The only way we can keep the Alton Domain on the Darkovan side is to have a strong Hastur man in command, Gabriel. Challenge him again before the Council; I don’t even think he wants to fight for it.”

“Lord of Light, sir! Do you honestly think—” Gabriel broke off. He said, “I can’t do it, Lord Hastur, and I won’t.”

“Do you want a half-Terran pawn of Sharra at the head of the Alton Domain?” Javanne demanded, staring at her husband.

“That’s for him to say,” said Gabriel steadily. “I took oath to obey any lawful command you gave me, Lord Hastur, but it isn’t a lawful command when you bid me challenge the rightful Head of my Domain. If you’ll pardon my saying so, sir, that’s a long way from being a lawful command.”

Old Hastur said impatiently “The important thing at this time is that the Domains should stand fast. Lew’s unfit—”

“If he’s unfit, sir—” and Gabriel looked troubled—“it’ll be apparent soon enough.”

Javanne said shrilly, “I thought they had deposed him as Kennard’s successor after the Sharra rebellion. And now both he and his brother are still tied up with Sharra—”

Regis said, “And so am I, sister; or weren’t you listening?”

She raised her eyes to him and said, disbelieving, “You?”

Regis reached, with hesitant fingers, for his matrix; fumbled at taking it from its silk wrapping. He remembered that Javanne had, years ago, taught him to use it, and she remembered too, for she raised her angry eyes and suddenly softened, and smiled at him. There was the old image in her mind, as if the girl she had been– herself motherless, trying to mother her motherless baby brother– had bent over him as she had so often done when he was small, swung him up into her arms—For a moment the hard-faced woman, the mother of grown sons, was gone, and she was the gentle and loving sister he had once known.

Regis said softly, “I am sorry, breda, but things don’t go away because you are afraid of them. I didn’t want you to have to see this.” He sighed and let the blue crystal fall into his cupped hand.

Raging, flaming in his mind, the form of fire…a great tossing shape, a woman, tall, bathed in flame, her hair rising like restless fires, her arms shackled in golden chains… Sharra!

When he had seen it six years ago at the height of the Sharra rebellion, his laranhad been newly waked; he had been, moreover, half dead with threshold sickness, and Sharra had been only another of the horrors of that time. When he had seen it briefly in Marius’s house, he had been too shocked to notice. Now something cold took him by the throat; his flesh crawled on his bones, every hair on his body rose slowly upright, beginning with his forearms, slowly moving over all his body. Regis knew, without knowing how he knew, that he looked upon a very ancient enemy of his race and his caste, and something in his body, cell-deep, bone-deep, knew and recognized it. Nausea crawled through his body and he felt the sour taste of terror in his mouth.

Confused, he thought, but Sharra was used and chained by the forge-folk, surely I am simply remembering the destruction of Sharra loosed, a city rising in flame…it is no worse than a forest fire—but he knew this was something worse, something he could not understand, something that fought to draw him into itself… recognition, fear, a fascination almost sexual in its import…

“Aaahh—” It was a half-drawn breath of horror; he heard, saw, feltJavanne’s mind, her terror reaching out, entangled. She clutched at the matrix under her own dress as if it had burned her, and Regis, with a mighty effort, wrenched his mind and his eyes from the Form of Fire blazing from his matrix. But Javanne clung, in terror and fascination…

And something in Regis, long dormant, unguessed, seemed to uncoil within him; as a skilled swordsman takes the hilt in his hand, without knowing what moves he will make, or which strokes he will answer, knowing only that he can match his opponent, he felt that strangeness rise, take over what he did next. He reached outinto the depths of the fire, and delicately picked Javanne’s mind loose, focusing so tightly that he did not even touch the Form of Fire… as if she were a puppet, and the strings had been cut, she slumped back fainting in her chair, and Gabriel caught her scowling.

“What did you do?” he demanded, “What have you done to her?”

Javanne, half-conscious, was blinking. Regis, with careful deliberation, wrapped up his matrix. He said, “It is dangerous to you too, Javanne. Don’t come near it again.”

Danvari Hastur had been staring, bewildered, as his grandson and granddaughter stared in terror, paralyzed, then, as they withdrew. Regis remembered, wearily, that his grandfather had little laran. Regis himself did not understand what he had done, only knew he was shaking down deep in the bones, exhausted, as weary as if he had been on the fire-lines for three days and three nights. Without knowing he was doing it, he reached for a plateful of hot rolls, smeared honey thickly on one and gobbled it down, feeling the sugar restoring him.

“It was Sharra,” Javanne said in a whisper. “But what did you do?”

And Regis could only mumble, shocked, “I haven’t the faintest idea.”

CHAPTER FOUR

« ^ »

Lew Alton’s narrative

I’ve never been sure how I got out of the Crystal Chamber. I have the impression that Jeff half-carried me, when the Council broke up in discord, but the next thing I remember clearly, I was in the open air, and Marius was with me, and Jeff. I pulled myself upright.

“Where are we going?”

“Home,” said Marius, “The Alton townhouse; I didn’t think you’d care for the Alton apartments, and I’ve never been there—not since Father left. I’ve been living here with Andres and a housekeeper or two.”

I couldn’t remember that I’d been to the town house since I was a very young child. It was growing dark; thin cold rain stung my face, clearing my mind, but fragments of isolated thought jangled and clamored from the passersby, and the old insistent beat:

… last command– return, fight for your brother’s rights… Would I never be free of that? Impatiently I struggled to get control as we came across the open square; but I seemed to see it, not as it was, dark and quiet, with a single light somewhere at the back, a servant’s night-light; but I saw it through someone else’s eyes, alive with light and warmth spilling down from open doors and brilliant windows, companionship and love and past happiness… I realized from Jeff’s arm around my shoulders that he was seeing it as it had been, and moved away. I remembered that he had been married, and that his wife had died long since. He, too, had lost a loved one—

But Marius was up the steps, calling out in excitement as if he were younger than I remembered him.

“Andres! Andres!” and a moment later the old coridomfrom Armida, friend, tutor, foster-father, was staring at me in astonishment and welcome.

“Young Lew! I—” he stopped, in shock and sorrow, as he saw my scarred face, the missing hand. He swallowed, then said gruffly, “I’m glad you’re here.” He came and took my cloak, managing to give my shoulder an awkward pat of affection and grief. I suppose Marius had sent word about father; mercifully, he asked no questions, just said “I’ve told the housekeeper to get a room ready for you. You too, sir?” he asked Jeff, who shook his head.

“Thank you, but I am expected elsewhere—I am here as Lord Ardais’s guest, and I don’t think Lew is in any shape for any long family conferences tonight.” He turned to me and said, “Do you mind?” and held his hand lightly over my forehead in the monitor’s touch, the fingers at least three inches away, running his hand down over my head, all along my body. The touch was so familiar, so reminiscent of the years at Arilinn—the only place I could remember where I had been wholly happy, wholly at peace—that I felt my eyes fill with tears.

That was all I wanted– to go back to Arilinn. And it was forever too late for that. With the hells in my brain that would not bear looking into, with the matrix tainted by Sharra… no, they would not have me in a Tower now.

Jeff’s hand was solid under my arm; he shoved me down in a seat. Through the remnant of the drugs which had destroyed my control, I felt his solicitude, Andres’s shock at my condition, and turned to face them, clenching my hand, aware of phantom pain as by reflex I tried to clench the missing hand too; wanting to scream out at them in rage, and realizing that they were all troubled for me, worrying about me, sharing my pain and distress.

“Keep still, let me finish monitoring you.” When he finished Jeff said, “Nothing wrong, physically, except fatigue and drug hangover from that damned stuff the Terrans gave him. I don’t suppose you have any of the standard antidotes, Andres?” At the old man’s headshake he said dryly, “No, I don’t suppose they’re the sort of thing that one can buy in an apothecary shop or an herb-seller’s stall. But you need sleep, Lew. I don’t suppose there’s any raivanninin the house—”

Raivanninis one of the drugs developed for work among Tower circles, linked in the mind of a telepathic circle…There are others: Kirian, which lowers the resistance to telepathic contact, is perhaps the most common. Raivanninhas an action almost the opposite of that of Kirian. It tends to shut down the telepathic functions. They’d given it to me, in Arilinn, to quiet, a little, the torture and horror which I was broadcasting after Marjorie’s death… quiet it enough so that the rest of the Tower circle need not share every moment of agony. Usually it was given to someone at the point of death or dissolution, or to the insane, so that they would not draw everyone else into their inner torment—”

“No,” Jeff said compassionately. “That’s not what I mean. I think it would help you get a night’s sleep, that’s all. I wonder—There are licensed matrix mechanics in the City, and they know who I am; First in Arilinn. I will have no trouble buying it.”

“Tell me where to go,” said a young man, coming swiftly into the room, “and I will get it; I am known to many of them. They know I have laran. Lew—” he came around and stood directly before me. “Do you remember me?”

I focused my eyes with difficulty, saw golden-amber eyes, strange eyes… Marjorie’s eyes! Rafe Scott flinched at the agony of that memory, but he came up and embraced me. He said, “I’ll find some raivanninfor you. I think you need it.”

“What are you doing in the city, Rafe?” He had been a child when I had drawn him, with Marjorie, into the circle of Sharra. Like myself, he bore the ineradicable taint, fire and damnation… no! I slammed my mind shut, with an effort that turned me white as death.

“Don’t you remember? My father was a Terran, Captain Zeb Scott. One of Aldaran’s tame Terrans.” He said it wryly, with a cynical lift of his lip, too cynical for anyone so young. He was Marius’s own age. I was beyond curiosity now; though I had heard Regis describing what he had seen, and knew that he was Marius’s friend. He didn’t stay, but went out into the rainy night, shrugging a Darkovan cloak over his head.

Jeff sat on one side of me; Marius on the other. We didn’t talk much; I was in no shape for it. It took all my energy for me to keep from curling up under the impact of all this.

“You never did tell me, Jeff, how you came to be in the city.”

“Dyan came to bring me,” he said. “I don’t want the Domain and I told him so; but he said that having an extra claimant would confuse the issue, and stall them until Kennard could return. I don’t think he was expecting you.”

“I’m sure he wasn’t,” Marius said.

“That’s all right, brother, I can live without Dyan’s affection,” I said. “He’s never liked me…” but still I was confused by that moment of rapport, when for a moment I had seen him through my father’s eyes…

… dear, cherished, beloved, sworn brother… even, once or twice, in the manner of lads, lovers… I slammed the thought away. In a sense the rejection was a kind of envy. Solitary in the Comyn, I had had few bredin, fewer to offer such affection even in crisis. Could it be that I envied my father that? His voice, his presence, were a clamor in my mind…

I should tell Jeff what had happened. Since Kennard had awakened the latent Alton gift, the gift of forced rapport, by violence when I was hardly out of childhood, he had been there, his thoughts overpowering my own, choking me, leaving me all too little in the way of free will, till I had broken free, and in the disaster of the Sharra rebellion, I had learned to fear that freedom. And then, dying, his incredible strength closing over my mind in a blast I could not resist or barricade…

Ghost-ridden; half of my brain burnt into a dead man’s memories…

Was I never to be anything but a cripple, mutilated mind and body? For very shame I could not beg Jeff for more help than he had given me already…

He said neutrally, “If you need help, Lew, I’m here,” but I shook my head.

“I’m all right; need sleep, that’s all. Who is Keeper at Arilinn now?”

“Miranie from Dalereuth; I don’t know who her family was—she never talks about them. Janna Lindir, who was Keeper when you were at Arilinn, married Bard Storn-Leynier, and they have two sons; but Janna put them out to foster, and came back as Chief Monitor at Neskaya. We need strong telepaths, Lew; I wish you could come back, but I suppose they’ll need you on the Council—”

Again I saw him flinch, slightly, at my reaction to that. I knew the state I was in, as well as he did; every transient emotion was broadcasting at full strength. Andres, Terran and without any visible laran, still noticed Marius’s distress; he had, after all, lived with a telepath family since before I was born. He said stolidly, “I can find a damper and put it on, if you wish.”

“That won’t be—” I started to say, but Jeff said firmly, “Good. Do that.” And before long the familiar unrhythmic pulses began to move through my mind, disrupting it. It blanked it out for the others—at least the specific content– but for me it substituted nausea for the sharper pain. I listened with half an ear to Marius telling Andres what had happened at the Council. Andres, as I had foreseen, understood at once what the important thing was.

“At least they recognized you; your right to inherit was challenged, but for once the old tyrant had to admit you existed,” snorted Andres. “It’s a beginning, lad.”

“Do you think I give a damn—” Marius demanded. “All my life I haven’t been good enough for them to spit on, and suddenly—”

“It’s what your father fought for all his life,” Andres said, and Jeff said quietly, “Ken would have been proud of you, Marius.”

“I’ll bet,” said the boy scornfully. “So proud he couldn’t come back even once—”

I bent my head. It was my fault, too, that Marius had had no father, no kinsman, no friend, but was left alone and neglected by the proud Comyn. I was relieved when Rafe came back, saying he had found a licensed technician in the street of the Four Shadows, and he had sold him a few ounces of raivannin. Jeff mixed it, and said, “How much—”

“As little as possible,” I said. I had had some experience with the chemical damping-drugs, and I didn’t want to be helpless, or unable to wake if I got into one of those terrible spiraling nightmares where I was trapped again in horrors beyond horrors, where demons of fire flamed and raged between worlds…

“Just enough so you won’t have to sleep under the dampers,” he said. To my cramping shame, I had to let him hold it to my lips, but when I had swallowed it, wincing at its biting astringency, I felt the disruptions of the telepathic damper gradually subsiding, mellowing, and slowly, gradually, it was all gone.

It felt strange to be wholly without telepathic sensitivity; strange and disquieting, like trying to hear under water or with clogged ears; painful as the awareness had been, now I felt dulled, blinded. But the pain was gone, and the clamor of my father’s voice; for the first time in days, it seemed, I was free of it. It was there under the thick blankets of the drug, but I need not listen. I drew a long, luxurious breath of calm.

“You should sleep. Your room’s ready,” Andres said. “I’ll get you upstairs, lad—and don’t bother fussing about it; I carried you up these stairs before you were breeched, and I can do it again if I have to.”

I actually felt as if I could sleep, now. With another long sigh, I stood up, catching for balance.

Andres said, “They couldn’t do anything about the hand, then?”

“Nothing. Too far gone.” I could say it calmly now; I had, after all, before that ghastly debacle when Dio’s child was born and died, learned to live with the fact. “I have a mechanical hand but I don’t wear it much, unless I’m doing really heavy work, or sometimes for riding. It won’t take much strain, and gets in my way. I can manage better, really, without it.”

“You’ll have your father’s room,” Andres said, not taking too much notice. “Let me give you a hand with the stairs.”

“Thanks. I really don’t need it.” I was deathly tired, but my head was clear. We went into the hallway, but as we began to mount the stairs, the entry bell pealed and I heard one of the servants briefly disputing; then someone pushed past him, and I saw the tall, red-haired form of Lerrys Ridenow.

“Sorry to disturb you here; I looked for you in the Alton suite in Comyn Castle,” he said. “I have to talk to you, Lew. I know it’s late, but it’s important.”

Tiredly, I turned to face him. Jeff said, “Dom Lerrys, Lord Armida is ill.” It took me a moment to realize he was talking about me.

“This won’t take long.” Lerrys was wearing Darkovan clothing now, elegant and fashionable, the colors of his Domain. In the automatic gesture of a trained telepath in the presence of someone he distrusts, I reached for contact; remembered: I was drugged with raivannin, at the mercy of whatever he chose to tell me. It must be like this for the headblind. Lerrys said, “I didn’t know you were coming back here. You must know you’re not popular.”

“I can live without that,” I said.

“We haven’t been friends, Lew,” he said. “I suppose this won’t sound too genuine; but I’m sorry about your father. He was a good man, and one of the few in the Comyn with enough common sense to be able to see the Terrans without giving them horns and tails. He had lived among the Terrans long enough to know where we would eventually be going.” He sighed, and I said, “You didn’t come out on a rainy night to give me condolences about my father’s death.”

He shook his head. “No,” he said, “I didn’t. I wish you’d had the sense to stay away. Then I wouldn’t have to say this. But here you are, and here I am, and I do have to say it. Stay away from Dio or I’ll break your neck.”

“Did she send you to say that to me?”

“I’m saying it,” Lerrys said. “This isn’t Vainwal. We’re in the Domains now, and—” He broke off. I wished with all my heart that I could read what was behind those transparent green eyes. He looked like Dio, damn him, and the pain was fresh in me again, that the love between us had not been strong enough to carry us through tragedy. “Our marriage ceremony was a Terran one. It has no force in the Domains. No one there would recognize it.” I stopped and swallowed. I had to, before I could say, “If she wanted to come back to me, I’d—I’d welcome it. But I’m not going to force it on her, Lerrys, don’t worry about that. Am I a Dry-towner, to chain her to me?”

“But a time’s coming when we’ll all be Terrans,” Lerrys said, “and I don’t want her tied to you then.”