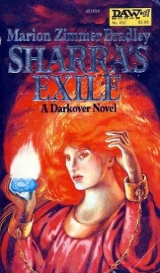

Текст книги "Sharra's Exile"

Автор книги: Marion Zimmer Bradley

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 27 страниц)

Firmly I clamped down on the growing panic. If I did not stop this now, my own fear and Regie’s could reinforce each other and we would both go into screaming hysterics. I caught at what I could remember of the Arilinn training, managed to steady my breathing, felt the panic subside.

Not so Regis; he was still sitting there, in the chair where I had shoved him, white with dread. I turned around and was surprised to hear my own voice, the steady, detached voice of a matrix mechanic, dispassionate, professionally soothing, as I had not heard it in more years than I liked to think about.

“I’m not a Keeper, Regis, and my own matrix, at the moment, is useless, as you know. I could try to deep-probe you and find out—”

He flinched. I didn’t blame him. The Alton gift is nothing to play games with, and I have known experienced technicians, Tower-trained for many years, refuse to face that fully focused gift of rapport. I can manage it, if I must, but I was not eager. It is not, I suppose, unlike rape, the deliberate overpowering of a mind, the forced submission of another personality, the ultimate invasion. Only the probably nonexistent Gods of Darkover know why such a Gift had been bred into the Alton line, to force rapport on an unwilling other, paralyze resistance. I knew Regis feared it too, and I didn’t blame him. My father had opened my own Gift in that way, when I was a boy—it had been the only way to force the Council to accept me, to show them that I, alien and half Terran, had the Alton Gift—and I had been ill for weeks afterward. I didn’t relish the thought of doing the same thing to Regis.

I said, “It might be that they could tell you in a Tower; some Keeper, perhaps—” and then I remembered that here in Comyn Castle was a Keeper. I tended to forget; Ashara of the Comyn Tower must be incredibly old now, I had never seen her, nor my father before me… but now Callina was there as her surrogate, and Callina was my kinswoman, and Regis’s too.

“Callina could tell you,” I said, “if she would.”

He nodded, and I felt the panic recede. Talking about it, calmly and detached, as if it were a simple problem in the mechanics of laran, had defused some of the fear.

Yet I too was uneasy. By the time I left the Crystal Chamber, even the halls and corridors were empty; the Comyn Council had scattered and gone their separate ways. Council was over. Nothing remained except the Festival Night ball, tomorrow. On the threshold of the Chamber, we encountered the Syrtis youngster; he almost ignored me, hurrying to Regis.

“I came back to see what had happened to you!” he demanded, and, as Regis smiled at him, I quietly took my leave, feeling I made an unwelcome third. As I went off alone, I identified one of my emotions; was I jealous of what Regis shared with Danilo? No, certainly not.

But I am alone, brotherless, friendless, alone against the Comyn who hate me, and there is none to stand by my side. All my life I had dwelt in my father’s shadow; and now I could not bear the solitude when that was withdrawn. And Marius, who should have stood at my side—Marius too was dead by an assassin’s bullet, and no one in the Comyn except Lerrys had even questioned the assassination. And—I felt myself tensing as I identified another element of my deep grief for Marius. It was relief; relief that I would not have to test him as my father had tested me, that I need not invade him ruthlessly and feel him die beneath that terrible assault on identity. He had died, but not at my hands, nor beneath my laran.

I had known my laran could kill, but I had never killed with it.

I went back to the Alton rooms, thoughtfully. They were home, they had been home much of my life, yet they seemed empty, echoing, desolate. It seemed to me that I could see my father in every empty corner, as his voice still echoed in my mind. Andres, puttering around, supervising the other servants in placing the belongings which had been brought here from the town house, broke off what he was doing as I came in, and hurried to me, demanding to know what had happened to me. I did not know that it showed on my face, whatever it was, but I let him bring me a drink, and sat sipping it, wondering again about what Regis had done in the Crystal Chamber. He had scared Beltran. But, probably, not enough.

I did not think Beltran was eager to plunge the Domains into war. Yet I knew his recklessness, and I did not think we could gamble on that; not when his outraged pride was at stake, the pride of the Aldarans.

I said to Andres, “You hear servants’ gossip; tell me, has Beltran moved into the Aldaran apartments here in Comyn Castle?”

Andres nodded glumly, and I hoped that he would find them filled with vermin and lice; they had stood empty since the Ages of Chaos. It said something about the Comyn that they had never been converted to other uses.

Andres stood over me, grumbling, “You’re not intending to go and pay a call on him there, I hope!”

I wasn’t. There was only one way in the world I would ever come again within striking range of my cousin, and that was if he had me bound and gagged. He had betrayed me before; he would have no further chance. Sunk in the misery of that moment, I confess, to my shame, that for a moment I played with the escape that Dan Lawton, in the Terran Zone, had offered me, to hide there out of reach of Sharra– but that was no answer, and it left Regis and Callina at the mercy of whatever unknown thing was working in the Comyn.

I was not altogether alone. The thought of Callina warmed me; I had pledged to stand beside her. And I had not yet spoken alone with my kinswoman Linnell, except over the grave of my brother. It was the eve of Festival Night, when traditionally, gifts of fruit and flowers are sent to the women of every family, throughout the Domains. Not the meanest household in Thendara would let tomorrow morning pass without at least a few garden flowers or a handful of dried fruits for the women of the household; and I had done nothing about a gift for Linnell. Truly, I had been too long away from Darkover.

There would be flower sellers and fruit vendors doing business in the markets of the Old Town, but as I stepped toward the door, I hesitated, unwilling again to show myself. Damn it, during the time I had lived with Dio, I had almost forgotten my scarred face, my missing hand, and now I was behaving as if I were freshly maimed—Dio! Where was Dio, had I truly heard her voice in the Crystal Chamber? I told myself sternly that it did not matter; whether Dio was here or elsewhere, if she chose not to come to me, she was lost to me. But still I could not make myself go down to ground level of the enormous castle, go out into the Old Town through Beltran’s damnably misnamed Honor Guard.

Some of them would have known me, remembered me…

At last, hating myself for the failure, I told Andres to see about some flowers for Linnell tomorrow. Should I send some to Dio too? I truly did not know the courtesies of the situation. Out there in the Empire, I knew, a separated husband and wife can meet with common courtesy; here on Darkover, it was unthinkable. Well, I was on Darkover now, and if Dio wanted nothing from me, she would probably not want a Festival gift either. With surging bitterness I thought, she has Lerrys to send her fruits and flowers. If Lerrys had been before me, at that moment, I think I would have hit him. But what would that settle? Nothing. After a moment I picked up a cloak, flung it about my shoulders; but when Andres asked where I was going, I had no answer for him.

My feet took me down, and down into courtyards and enclosed gardens, through unfamiliar parts of the castle. At one point I found myself in a court beneath the deserted Aldaran apartments—deserted all my life, till now. Half of me wanted to go in there and face Beltran, demand—demand what? I did not know. Another part of me wanted, cravenly, to walk through the city, take refuge in the Terran Zone, and then– then what? I could not leave Darkover, not while the Sharra matrix was here; I had tried. And tried again. It would mean death, a death neither quick nor easy.

Maybe I would be better dead, even that death, so that I was free in death of Sharra… and again it seemed to me that the Form of Fire raged before my eyes, a thrilling in my blood, cold terror and raging, ravening flame like ichor in my veins—

No; this was real. I tensed, looking up at the hills behind the city.

Somewhere there, strange flames burned, an incredible ninth-level matrix twisted space around itself, a gateway opened, and the fire ran in my veins– There was fire before my eyes, fire all through my brain—

No! I am not sure that I did not scream that furious denial aloud; if I did no one heard me, but I heard the echoes in the courtyard around me, and slowly, slowly, came back to reality. Somewhere out there, Kadarin ran loose, and with him the Sharra matrix, and Thyra whom I had hated, loved, desired and feared… but I would die before they dragged me back into thatagain. Deliberately, fighting the call in my mind, I raised the stump of my arm and slammed it down, hard, on stone. The pain was incredible; it made me gasp, and tears came to my eyes, but that pain was real;outraged nerves and muscles and bones, not a phantom fire raging in my brain. I set my teeth and turned my back on the hills, and that call, that siren call which throbbed seductively in my mind, and went into the Castle.

Callina. Callina could drive these devils from my mind.

I had not been inside the Aillard wing of Comyn Castle for many years, not since I was a child. A silent servant met me, managed not to blink more than once at the ruin of my face. He showed me into a reception room where, he said, I would find DomnaCallina and Linnell with her.

The room was spacious and brilliant, filled with sunshine and silken curtains, green plants and flowers growing in every niche, like an indoor garden. Soft notes of a harp echoed through the room; Linnell was playing the rryl. But as I came in she pushed it aside and ran to me, taking an embrace and kiss with the privilege of a foster-sister, drawing back, hesitant, as she touched the stump of an arm.

“It’s all right,” I said. “You can’t hurt me. Don’t worry about it, little sister.” I looked down at her, smiling. She was the only person on this world who had truly welcomed me, I thought; the only one who had had no thought of what my coming would mean. Even Marius had had to think of what it would mean in terms of Domain-right. Even Jeff; he might have had to leave Arilinn and take his place in Council.

“Your poor hand,” she said. “Couldn’t the Terrans do anything for it?”

Even to Linnell I didn’t want to talk about it. “Not much,” I said, “but I have a mechanical hand I wear when I don’t want to be noticed. I’ll wear it when I dance with you on Festival Night, shall I?”

“Only if you want to,” she said seriously. “I don’t care what you look like, Lew. You’re always the same to me.”

I hugged her close, warmed as much by her accepting smile as by the words. I suppose Linnell was a beautiful woman; I have never been able to see her as anything but the little foster-sister with whom I’d raced breakneck over the hills; I’d spanked her for breaking my toys or borrowing them without leave, comforted her when she was crying with toothache. I said, “You were playing the rryl… play for me, won’t you?”

She took up the instrument again and began to play the ballad of Hastur and Cassilda:

The stars were mirrored on the shore,

Dark was the lone immortal moor,

Silent were rocks and trees and stone—

Robardin’s daughter walked alone,

A web of gold between her hands

On shining spindle burning bright…

I had heard Dio singing it, though Dio had no singing voice to speak of—I wondered, where was Callina? I should speak with her—

Linnell gestured, and I saw, in a niche beyond the fireplace, Callina and Regis Hastur, seated on a soft divan and so absorbed in what they were saying that neither had heard me come into the room. I felt a momentary flare of jealousy– they looked so comfortable, so much at peace with each other—then Callina looked up at me and smiled, and I knew I had nothing to fear.

She came forward; I wanted to take her in my arms, into that embrace which was so much more than the embrace I would have given a kinswoman; instead she reached out and touched my wrist, the feather touch with which a working Keeper would have greeted me, and with that automatic gesture, frustration slipped between us like an unsheathed sword.

A Keeper. Never to be touched, never to be desired, even by a defiling thought… angry frustration, and at the same time, reassurance; this is how she would have greeted me if we were both back in Arilinn, where I had been happy… even had we been acknowledged lovers for years, she would no more have touched me than this.

But our eyes met, and she said gravely, “Ashara will see you, Lew. It is the first time, I think, in more than a generation, that she has agreed to speak with anyone from outside. When I spoke to her of the Sharra matrix, she said I might bring you.”

Regis said, “I would like to speak with her, too. It may be that she would know something of the Hastur Gift…” but, he broke off at Callina’s cold frown.

“She has not asked for you. Even I cannot bring anyone into her presence unless she wishes it.”

Regis subsided as if she had struck him. I blinked, staring aghast at this new Callina, the impassive mask of her face, the eyes and voice of a cold, stony stranger. Only a moment, and she was again the Callina I knew, but I had seen, and I was puzzled and dismayed. I would have said something more, even to reassure Regis that we would ask the ancient leronisto grant him an audience, but Linnell claimed me again.

“Are you going to take him away at once? When we have not seen each other for so many years? Lew, you must tell me about Terra, about the worlds in the Empire!”

“There will be time enough for that, certainly,” I said, smiling, looking at the fading light. “It is not yet nightfall… but there’s nothing good to tell of Terra, chiya;I have no good memories. Mostly I was in hospitals…” and as I said the word I remembered another hospital in which not I, but Dio had been the patient, and a certain darkhaired, sweet-faced young nurse. “Did you know, Linnie–no, of course, you couldn’t know; you have a perfect double on Vainwal; so like you that at first I called her by your name, thought it was you yourself!”

“Really? What was she like?”

“Oh, efficient, competent—even her voice was like yours,” I said. And then I stopped, remembering the horror of that night, the shockingly deformed, monstrous form that should have been my son… I was strongly barriered, but Linnell saw the twitching of my face and put up her hand to stroke my scarred cheek.

“Foster-brother,” she said, giving the word the intimate inflection that made it a term of endearment, “don’t talk about hospitals and sickness and pain. It’s all over now, you’re here at home with us. Don’t think about it.”

“And there are enough troubles here on Darkover to make you forget whatever troubles you may have had in the Empire,” said Regis, with a troubled smile, joining us at the window, where the sun had faded, blurred by the evening clouds. “Council was not properly adjourned; I doubt we’ve heard the last of that. Certainly not the last of Beltran…” and Callina, hearing the name, shuddered. She said, looking impatiently at the clouds, “Come, we must not keep Ashara waiting.”

A servant folded her into a wrap that was like a gray shadow. We went out and down the stairs, but at the first turning, something prompted me to turn back; Linnell stood there, framed in the light of the doorway, copper highlights caught in her brown hair, her face serious and smiling; and for a moment, that out-of-phase time sense that haunts the Alton gift, a touch perhaps of the precognition I had inherited from the Aldaran part of my blood, made me stare, unfocused, as past, present, future all collapsed upon themselves, and I saw a shadow falling on Linnell, and a dreadful conviction—

Linnell was doomed… the same shadow that had darkened my life would fall on Linnell and cover her and swallow her—

“Lew, what’s the matter?”

I blinked, turning to Callina at my side. Already the certainty, that sick moment when my mind had slid off the time track, was fading like a dream in daylight. The confusion, the sense of tragedy, remained; I wanted to rush up the stairs, snatch Linnell into my arms as if I could guard her from tragedy… but when I looked up again the door was closed and Linnell was gone.

We went out through the archway and into a courtyard. The light rain of early summer was falling, and though at this season it would not turn to snow, there were little slashes of sleet in it. Already the lights were fading in the Old City, or could not come through the fog; but beyond that, across the valley, the brilliant neon of the Trade City cast garish red and orange shadows on the low clouds. I went to the railed balcony that looked down on the valley, and stood there, disregarding the rain in my face. Two worlds lying before me; yet I belonged to neither. Was there any world in all the star-spanning Empire where I would feel at home?

“I would like to be down there tonight,” I said wearily, “or anywhere away from this Hell’s castle—”

“Even in the Terran Zone?”

“Even in the Terran Zone.”

“Why aren’t you, then? There is nothing keeping you here,” Callina said, and at the words I turned to her. Her cobweb cloak spun out on the wind like a fine mist as I pulled her into my arms. For a moment, frightened, she was taut and resisting in my arms; then she softened and clung to me. But her lips were closed and unresponsive as a child’s under my demanding kiss, and it brought me to my senses, with the shock of déjà vu…somewhere, sometime, in a dream or reality, this had happened before, even the slashes of rain across our faces…She sensed it too, and put up her hands between us, gently withdrawing. But then she let her head drop on my shoulder.

“What now, Lew? Merciful Avarra—what now?”

I didn’t know. Finally I gestured toward the crimson smear of garish neon that was the Trade City.

“Forget Beltran. Marry me—now—tonight, in the Terran Zone. Confront the Council with an accomplished fact and let them chew on it and swallow it—let them solve their own problems, not hide behind a woman’s skirts and think they can solve them with marriages!”

“If I dared—” she whispered, and through the impassive voice of a trained Keeper, I felt the tears she had learned not to shed. But she sighed, putting me reluctantly away again. She said, “You may forget Beltran, but he will not go away because we are not there. He has an army at the gates of Thendara, armed with Terran weapons. And beyond that– she hesitated, reluctant, and said, “Can we so easily forget– Sharra?”

The word jolted me out of my daydream of peace. For the first time in years, Sharra had not even been a whisper of evil in my mind; in her arms I had actually forgotten. Callina might be bound to the Tower by her vows as Keeper, but I was not free either. Silent, I turned away from the balconied view of the twin cities below me, and let her lead me down another flight of stairs and across another series of isolated courtyards, until I was all but lost in the labyrinth that was Comyn Castle.

Both of us, lost in the maze our forefathers had woven for us…

But Callina moved unerringly through the puzzling maze, and at last led me into a door where stairways led up and up, then through a hidden door, where we stood close together as, slowly, the shaft began to rise.

This Tower—so the story goes—was built for the first of the Comyn Keepers when Thendara was no more than a village of wicker-woven huts crouching in the lee of the first of the Towers. It went far, far into our past, to the days when the fathers of the Comyn mated with chieriand bred strange nonhuman powers into our line, and Gods moved on the face of the world among humankind, Hastur who was the son of Aldones who was the son of light… I told myself not to be superstitious. This Tower was ancient indeed, and some of the old machinery from the Ages of Chaos survived here, no more than that. Lifts that moved of themselves, by no power I could identify, were commonplace enough in the Terran Zone, why should it terrify me here? The smell of centuries hung between the walls, in the shadows that slipped past, as if with every successive rising we moved further back into the very Ages of Chaos and before– at last the shaft stopped, and we were before a small panel of glass that was a door, with blue lights behind it.

I saw no handle or doorknob, but Callina reached forward and it opened. And we stepped into… blueness.

Blue, like the living heart of a jewel, like the depths of a translucent lake, like the farther deeps of the sky of Terra at midday. Blue, around us, behind us, beneath us. Uncanny lights so mirrored and prismed the room that it seemed to have no dimensions, to be at once immeasurably large and terribly confined, to be everywhere at once. I shrank, feeling immense spaces beneath me and above me, the primitive fear of falling; but Callina moved unerringly through the blueness.

“Is it you, daughter and my son?” said a low clear voice, like winter water running under ice. “Come here. I am waiting for you.”

Then and only then, in the frosty dayshine, could I focus my eyes enough in the blueness to make out the great carven throne of glass, and the pallid figure of a woman seated upon it.

Somehow I would have thought that in this formal audience Ashara would wear the crimson robes of ceremonial for a Keeper. Instead she wore robes that so absorbed and mirrored the light that she was almost invisible; a straight tiny figure, no larger than a child of twelve. Her features were almost fleshlessly pure, as unwrinkled as Callina’s own, as if the very hand of time itself had smoothed its own marks away. The eyes, long and large, were colorless too, though in a more normal light they might have been blue. There was a faint, indefinable resemblance between the young Keeper and the old one, as if Ashara were a Callina incredibly more ancient, or Callina an embryo Ashara, not yet ancient but bearing the seeds of her own translucent invisibility. I began to believe that the stories were true; that she was all but immortal, had dwelt here unchanged while the worlds and the centuries passed over her and beyond her…

She said, “So you have been beyond the stars, Lew Alton?”

It would not be fair to say the voice was unkind. It was not human enough for that. Detached, unbelievably remote; it was all of that. It sounded as if the effort of conversing with real, living persons was too much for her, as if our coming had disturbed the crystalline peace in which she dwelt.

Callina, accustomed to this—or so I suppose—murmured, “You see all things, Mother Ashara. You know what we have to face.”

A flicker of emotion passed over the peaceful face, and she seemed to solidify, to become less translucent and more real. “Not even I can see all things. I have no power, now, outside this place.”

Callina murmured, “Yet aid us with your wisdom, Mother.”

“I will do what I must,” she said, remotely. She gestured. There was a transparent bench at her feet—glass or crystal; I had not seen it before, and I wondered why. Maybe it had not been there or maybe she had conjured it there; nothing would have surprised me now. “Sit there and tell me.”

She gestured at my matrix. “Give it to me, and let me see—”

Now, remembering, telling, I wonder whether any of this happened or whether it was some bizarre dream concealing reality. A telepath, even an Arilinn-trained telepath, simply does not do what I did then; without even thinking of protest, I slipped the leather thong on which my matrix was tied over my head with my good hand, fumbled a little with the silken wrappings, and handed it to her, without the slightest thought of resisting. I simply put it into her hand.

And this is the first law of a telepath; nobody touches a keyed matrix, except your own Keeper, and then only after a long period of attunement, of matching resonances. But I sat there at the feet of the ancient sorceress, and laid the matrix in her hand without stopping to think, and although something in me was tensed against incredible agony… I remembered when Kadarin had stripped me of my matrix, and how I had gone into convulsions…nothing happened; the matrix might have been safely around my neck.

And I sat there peacefully and watched it.

Deep within the almost-invisible blue of the matrix were fires, strange lights… I saw the glow of fire, and the great raging shimmer… Sharra! Not the Form of Fire which had terrified us in Council, but the Goddess herself, raging in flame—Ashara waved her hand and it disappeared. She said, “Yes, that matrix I know of old… and yours has been in contact with it, am I right?”

I bowed my head and said, “You have seen.”

“What can we do? Is there any way to defend against—”

She waved Callina to silence. “Even I cannot alter the laws of energy and mechanics,” she said. Looking around the room, I was not so sure. As if she had heard my thoughts, she said, “I wish you knew less science of the Terrans, Lew.”

“Why?”

“Because now you look for causes, explanations, the fallacy that every event must have a preceding cause… matrix mechanics is the first of the non-causal sciences,” she said, seeming to pick up that Terran technical phrase out of the air or from my mind. “Your very search for structure, cause and reality produces the cause you seek, but it is not the real cause… does any of this make sense to you?”

“Not very much,” I confessed. I had been trained to think of a matrix as a machine, a simple but effective machine to amplify psi impulses and the electrical energy of the brain and mind.

“But that leaves no place for such things as Sharra,” Ashara said. “Sharra is a very real Goddess– No, don’t shake your head. Perhaps you could call Sharra a demon, though She is no more a demon than Aldones is a God– They are entities, and not of this ordinary three-dimensional world you inhabit. Your mind would find it easier to think of them as Gods and Demons, and of your matrix, and the Sharra matrix, as talismans for summoning those demons, or banishing them…They are entities from another world, and the matrix is the gateway that brings them here,” she said. “You know that, or you knew it once, when you managed to close the gateway for a time. And for such a summoning Sharra will always have Her sacrifice; so she had your hand, and Marjorie gave up her life—”

“Don’t!” I shuddered.

“But there is a better weapon of banishing,” Ashara said. “What says the legend…”

Callina whispered, “Sharra was bound in chains by the son of Hastur, who was the Son of Aldones who was the Son of Light…”

“Rubbish,” I said boldly. “Superstition!”

“You think so?” Ashara seemed to realize she was still holding my matrix; she handed it carelessly back to me and I fumbled it into the silken wrappings and into its leather bag, put it back around my neck. “What of the shadow-sword?”

That too was legend; Linnell had sung it tonight, of the time when Hastur walked on the shores of the lake, and loved the Blessed Cassilda. The legend told of the jealousy of Alar, who had forged in his magical forge a shadow-sword, meant to banish, not to slay. Pierced with this sword, Hastur must return to his realms of light… but the legend recounted how Camilla, the damned, had taken the place of Cassilda in Hastur’s arms, and so received the shadow-blade in her heart, and passed away forever into those realms—

I said, hesitating, “The Sharra matrix is concealed in the hilt of a sword… tradition, because it is a weapon, no more—”

Ashara asked, “What do you think would happen to anyone who was slain with such a sword as that?”

I did not know. It had never occurred to me that the Sword of Sharra could be used as a sword, though I had hauled the damnable thing around half the Galaxy with me. It was simply the case the forge-folk had made to conceal the matrix of Sharra. But I found I did not like thinking of what would happen to anyone run through by a sword possessed and dominated by Sharra’s matrix.

“So,” she said, “you are beginning to understand. Your forefathers knew much of those swords. Have you heard of the Sword of Aldones?”

Some old legend… yes. “It lies hidden among the holy things at Hali,” I said, “spelled so that none of Comyn blood may come near, to be drawn only when the end of Comyn is near; and the drawing of that sword shall be the end of our world—”

“The legend has changed, yes,” said Ashara, with something which, in a face more solid, more human, might have been a smile. “I suppose you know more of sciences than of legend– Tell me, what is Cherilly’s Law?”

It was the first law of matrix mechanics; it stated that nothing was unique in space and time except a matrix; that every item in the universe existed with one and only one exactduplicate, except for a matrix; a matrix was the only thing which was wholly unique, and therefore any attempt to duplicate a matrix would destroy it, and the attempted duplicate.

“The Sword of Aldones is the weapon against Sharra,” said Ashara. But I knew enough of the holy things at Hali to know that if the Sword of Aldones was concealed there, it might as well be in another Galaxy; and I said so.

There are things like that on Darkover; they can’t be destroyed, but they are so dangerous that even the Comyn, or a Keeper, can’t be trusted with them; and all the ingenuity of the great minds of the Ages of Chaos had been bent to concealing them so that they cannot endanger others.

The rhu fead, the holy Chapel at Hali… all that remained of Hali Tower, which had burned to the ground during the Ages of Chaos… was such a concealment. The Chapel itself was guarded like the Veil at Arilinn; no one not of Comyn blood may penetrate the Veil. It is so spelled and guarded with matrixes and other traps that if any outsider, not of the true Comyn blood, should step inside, his mind would be stripped bare; by the time he or she got inside, he would be an idiot without enough directive force to know or remember why he had come there.