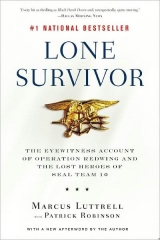

Текст книги "Lone survivor"

Автор книги: Marcus Luttrell

Жанры:

Военная история

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 23 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

And before he went, he explained he had a close friend who owned a construction company in Houston and wondered if there was anything Marcus might like when he came home.

Mom explained how I had always wanted a little space of my own where I could...well...chill, as the late Shane Patton would undoubtedly have expressed it. And perhaps a small extension off my lower-floor bedroom might be really nice. She was thinking rock-bottom price, and maybe she and Dad could manage that.

Next thing that happened, she said, two of the biggest trucks she’d ever seen came rolling into the drive, accompanied by a crane and a mechanical digger, a couple of architects, site engineers, and God knows what else. Then, Mom says, a team of around thirty guys, working twenty-four hours a day in shifts over three days, built me a house!

Scott Whitehead just said he was proud to have done a small favor for a very great Texan (Christ! He meant me, I think). And he still calls Mom every day, just to check we’re all okay.

Anyway, Morgan and I moved in, freeing up space for the stream of SEALs who still kept coming to see us. And I stayed home with the family, resting for two weeks, during which time Mom fought a fierce running battle with the Pepsi bottle bug, trying to get some weight on me.

Scott Whitehead’s boys had thought of everything. They even had the house phone wired up in my new residence, and the first call I received was a real surprise. I picked it up and a voice said, “Marcus, this is George Bush. I was forty-one.”

Jesus! This was the forty-first president of the United States. I knew that real quick. President Bush lives in Houston.

“Yessir,” I replied. “I very definitely know exactly who you are.”

“Well, I just called you to tell you how proud we all are of you. And my son’s real proud, and he wants you to know the United States of America is real proud of you, your gallantry, and your courage under fire.”

Hell, you could tell he was a military man, right off. I knew about his record, torpedo bomber pilot in the Pacific, World War II, shot down by the Japanese, Distinguished Flying Cross. The man who appointed General Colin Powell as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs. Victor of the Gulf War.

Are you kidding! “I’m George, forty-one, calling you to let you know how proud we are of you!” That really broke me up. He told me if I needed anything, no matter what, “be sure to call me.” Then he gave me his phone number. How about that? Me, Marcus? I mean, Jesus, he didn’t have to do that. Are Texans the greatest people in the world or what? Maybe you don’t think so, but I bet you see my point.

I was thrilled President Bush had called. And I thanked him sincerely. I just told him at the end, “Anything shakes loose, sir, I’ll be sure to call. Yessir.”

By mid-August, still being in the U.S. Navy, I had to go back to Hawaii (SDV Team 1). During my two weeks there I had a visit from the chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Mike Mullin, direct from the Pentagon.

He asked me to come over to the commanding officer’s office and promoted me right there on the spot, made me a Petty Officer First Class, no bullshit.

He’s the head of the U.S. Navy. And that was the greatest honor I had ever received. It was a moment I will never forget, just standing there in the presence of Admiral Mullin. He told me he was very proud of me. And it doesn’t get a whole lot bigger than that. I nearly cracked up.

Perhaps civilians might not appreciate why an honor like that means all the world to all of us; that sacred recognition that you have served your country well, that you have done your duty and somehow managed to live up to the highest possible expectations.

Even though it may seem like a strange ritual in a foreign tribe, kinda like lokhay, probably, I hope y’all get my drift.

Anyway, he asked me if there was anything he could do for me and I told him there was just one thing. I had with me the Texas patch I’d worn on my chest throughout my service in Afghanistan, fighting the Taliban and al Qaeda. This is the patch that bears the Lone Star. It was burned from the blast of that last RPG, and it was still blood-spattered, though I’d tried to get it cleaned. But I’d wrapped it in plastic, and you could see the Star of Texas clearly. And I asked Admiral Mullin if he could give it to the president of the United States.

He replied that he most certainly would and that he believed that President George W. Bush would be honored to have it.

“Would you like to send a brief letter to the president to accompany the battle patch?” Admiral Mullin asked me.

But I told him no. “I’d be grateful if you’d just give it to him, sir. President Bush is a Texan. He’ll understand.”

I had another request to make as well, but I restricted that to my immediate superiors. I wanted to go back to Bahrain and rejoin my guys from SDV Team 1 and ultimately bring them home at the conclusion of their tour of duty.

“I deployed with them, and I want to come back with them,” I said, and my very good friend Mario, the officer in charge of Alfa Platoon, considered this to be appropriate. And on September 12, 2005, I flew back to the Middle East, coming in to land at the U.S. air base on Muharraq Island, same place I’d left with Mikey, Axe, Shane, James, and Dan Healy, bound for Afghanistan, five months ago. I was the only one left.

They drove me out over the causeway, back to the American base up in the northeast corner of the country on the western outskirts of the capital city of Manama. We drove through the downtown area, through the places where people made it so plain they hated us, and this time I admit there was an edge of wari-ness in my soul. I knew now, firsthand, what jihadist hatred was.

I was reunited with my guys, and I stayed in Bahrain until late October. Then we all returned to Hawaii, while I prepared for another arduous journey, the one I had promised myself, promised my departed brothers in my prayers, and promised the families, whenever I could. I intended to see all the relatives and to explain what exemplary conduct all of their sons, husbands, and brothers had displayed on the front line of the battle against world terror.

I suppose, in a sense, I was filling in a part of me, which had missed seeing the outpouring of grief as, one by one, my teammates returned from Afghanistan. I had missed the funerals, which mostly took place before I returned. And the memorial services immaculately conducted by the navy for my fallen comrades.

For instance, the funeral of Lieutenant Mikey Murphy on Long Island, New York, was enormous. They closed down entire roads, busy roads. There were banners hanging across the highway on the Long Island Expressway in memory of a Navy SEAL who had paid the ultimate price in our assault on the warriors of al Qaeda.

There were police escorts for the cortege as thousands of ordinary people turned out to pay their last respects to a local son who had given everything for his country. And they did not even know a quarter of what he had given. Neither did anyone else. Except for me.

I was shown a picture of the service at the cemetery graveside. It was held in a slashing downpour of rain, everyone soaked, with the stone-faced Navy SEALs standing there in dress uniform, solemn, unflinching in the rainstorm, as they lowered Mikey into the endless silence of the grave.

Every one of the bodies was flown home accompanied by a SEAL escort who wore full uniform and stood guard over each coffin, which was draped in the Stars and Stripes. As I mentioned, even in death, we never leave anyone behind.

They closed Los Angeles International Airport for the arrival of James Suh’s plane. There were no arrivals and no takeoffs permitted while the aircraft was making its approach and landing. Nothing, until the escort had brought out the coffin and placed it in the hearse.

The State of Colorado damn near closed down for the arrival of the body of Danny Dietz, because the story of his heroism on the mountain had somehow been leaked to the press. But like the good citizens of Long Island, the people of Colorado never knew even a quarter of what that mighty warrior had done in the face of the enemy, on behalf of our nation.

They actually did close down the entire city of Chico, in northern California, when Axe came home. It’s a small town, situated around seventy-five miles north of Sacramento, with its own municipal airport. The escort was met by an honor guard which carried out the coffin in front of a huge crowd, and the funeral a day later stopped the entire place in its tracks, so serious were the traffic jams.

It was all just people trying to pay their last respects. The same everywhere. And I am left feeling that no matter how much the drip-drip-drip of hostility toward us is perpetuated by the liberal press, the American people simply do not believe it. They are rightly proud of the armed forces of the United States of America. They innately understand what we do. And no amount of poison about our alleged brutality, disregard of the Geneva Convention, and abuse of the human rights of terrorists is going to change what most people think.

I doubt any editor of any media outfit would get a reception like the SEALs earned, even though these combat troops had achieved their highest moments in the enforced privacy of the Hindu Kush. Perhaps the media offered the American public a poisoned chalice and then chugged it back themselves.

Some members of the media might think they can brainwash the public any time they like, but I know they can’t. Not here. Not in the United States of America.

Certainly on our long journey to visit the relatives, we were met only with warmth, friendship, and gratitude as representatives of the U.S. Navy. I think our presence in those scattered homes all over the country demonstrated once and for all that the memories of those beloved men will be forever treasured, not only by the families, but by the navy they served. Because the U.S. Navy cares enormously about these matters. Believe me, they really care.

The moment I suggested to my superiors that the remaining members of Alfa Platoon should make the journey, the navy offered their support and immediately agreed we should all go and that they would pay every last dollar the trip might cost.

We arrived back in San Diego and hired three SUVs. Then we drove up to Las Vegas to meet the family of my assistant Shane Patton, who died in the helicopter crash on the mountain. We arrived on Veterans Day. They made us guests of honor at the graveside for the memorial service. It was very upsetting for me. Shane’s dad had been a SEAL, and he understood how well I knew his son. I did the best I could.

Then we flew to New York to see Mikey’s mother and fiancée, and after that I went to Washington, D.C., to see the parents of Lieutenant Commander Eric Kristensen, our acting commanding officer, the veteran SEAL commanding officer who dropped everything that afternoon and rushed out to the helicopter, piling in with the guys, slamming a magazine into his rifle, and telling them Mikey needed every gun he could get. I think it was Eric to whom Mikey spoke when he made that last fateful phone call.

I told Admiral Kristensen, his father, that Eric would always be a hero to me, as he was to all of those who died with him on the mountain. Our CO was buried at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis.

We went to Arlington National Cemetery afterward to visit the graves of Lieutenant Mike McGreevy Jr. and Petty Officer First Class Jeff Lucas, of Corbett, Oregon. They both died in the helicopter and were laid to rest shoulder to shoulder in Arlington, as they had died in the Hindu Kush.

Next we flew back across the country to visit the huge family of Petty Officer James Suh. Everyone came to the cemetery to say a prayer for one of the most popular guys in the platoon.

Chief Dan Healy is buried in the military cemetery at Point Loma, San Diego, not far from Coronado. We all made the journey to northern California to see his family. Then we drove to Chico, and I told Axe’s wife, Cindy, how hard he had fought, what a hero he was, and how his final words to me were “tell Cindy I love her.”

Danny Dietz was from Colorado, and that’s where he was buried. But his family lived in Virginia near the base at Virginia Beach. I went to see his very beautiful, dark-haired wife, Patsy, and tried the best I could to explain what a critical role he had played in our team and how, in the end, he went down fighting as bravely as any man who ever served in the U.S. Armed Forces.

But grief like Patsy suffered is very hard to assuage. I know she felt her loss had smashed her life irrevocably, though she would try to put it together. But she sat with Danny’s two big dogs, and before I went, she said simply, “I just know there will never be another man like Danny.”

No argument from me about that.

As the year drew to an end, my injuries improved but remained, and I was posted back to Coronado. I detached from SDVT 1 and joined SEAL Team 5, where I was appointed leading petty officer (LPO) to Alfa Platoon. Like all SEAL platoons, it has a near-clockwork engine. The officer is responsible, the chief is in charge, the LPO runs it. They even gave me a desk, and the commanding officer, Commander Rico Lenway, instantly became like a father to me, as did Master Chief Pete Naschek, a super guy and veteran of damn near everywhere.

But it was a very reflective time for me, returning to Coronado, where I had not lived since BUD/S seven years ago. I walked back down to the beach where I’d first learned the realities of life as a Navy SEAL and what was expected and what I must tolerate; the cold, the freezing cold and the pain; the ability to obey an order instantly, without question, without rancor, the bedrocks of our discipline.

Right here I’d run, jumped, heaved, pushed ’em out, swum, floundered, and strived to within an inch of my life. I’d somehow kept going while others fell by the wayside. A million hopes and dreams had been smashed right here on this tide-washed sand. But not mine, and I had a funny feeling that for me this beach would forever be haunted by the ghost of the young, struggling Marcus Luttrell, laboring to keep up.

I walked back to my first barracks and nearly jumped out of my boots when that howling decom plant screamed into action. And I went and stood by the grinder, where the SEAL commanders had finally offered me warm wishes after presenting me with my Trident. Where I had first shaken the hand of Admiral Joe Maguire.

I looked at the silent bell outside the BUD/S office and at the place where the dropouts leave their helmets. Soon there would be more helmets, when the new BUD/S class began. Last time I was here I’d been in dress uniform, along with a group of immaculately turned-out new SEALs, many of whom I had subsequently served with.

And it occurred to me that any one of them, on any given day, would have done all the same things I had done in my last combat mission in the Hindu Kush. I wasn’t any different. I was just, I hoped, the same Texas country boy who’d come through the greatest training system on earth, with the greatest bunch of guys anyone could ever meet. The SEALs, the warriors, the front line of United States military muscle. I still get a lump in my throat when I think of who we all are.

I remember my back ached a bit as I stood there on the grinder, lost in my own thoughts, and my wrist, as ever, hurt, pending another operation. And I suppose I knew deep down I would never be quite the same physically, never as combat-hard as I once was, because I cannot manage the running and climbing. Still, I never was Olympic standard!

But I did live my dream, and then some, and I guess I’ll be asked many times whether it had all been worth it in the end. And my answer will always be the same one I gave so often on my first day.

“Affirmative, sir.” Because I came through it, and I have my memories, and I wouldn’t have traded any of it, not for the whole world. I’m a United States Navy SEAL.

Epilogue: Lone Star

On September 13, 2005, Danny Dietz and Matthew Axelson were awarded the highest honor which either the United States Navy or the Marine Corps can bestow on anyone – the Navy Cross for combat heroism. I was summoned to the White House to receive mine on July 18 the following year.

I was accompanied by my brothers, Morgan and Scottie, my mom and dad, and my close friend Abbie. SEAL Team 5’s Commander Lenway and Master Chief Pete Naschek were also there, with Lieutenant Drexler, Admiral Maguire’s aide.

Attired in full dress blues, my new Purple Heart pinned on my chest, close to my Trident, I walked into the Oval Office. The president of the United States, George W. Bush, stood up to greet me.

“It’s an honor to meet you, sir,” I said.

And the president gave me that little smile of his, which I took to mean, We’re both Texans, right? And he said, a little bit knowingly, “It’s my pleasure to meet you, son.”

He looked at the cast on my left wrist, and I told him, “I’m just trying to get back into the fight, sir.”

I shook his hand, and he had a powerful handshake. And he looked me right in the eye with a hard, steady gaze. Last time anyone looked at me like that was Ben Sharmak in Afghanistan. But that was born of hatred. This was a look between comrades.

Our handshake was prolonged and, for me, profound. This was my commander in chief, and right now I had his total attention, as I would have every time he spoke to me. President Bush does that naturally, speaking as if there is no one else in the room for him. This was one powerful man.

I remember I wanted to tell him how all my buddies love him, believe in him, and that we’re out there ready to bust our asses for him anytime he needs us. But he knows that. He’s our guy. Even Shane in his leopard-skin coat recognized our C in C as “a real dude.”

President Bush seemed to know what I was thinking. And he slapped me on the shoulder and said, “Thank you, Marcus. I’m proud of you, son.”

I have no words to describe what that meant to me, how much it all mattered. I came to attention, and Lieutenant Drexler read out my citation. And the president once more came toward me. In his hand he carried the fabled Navy Cross, with its dark blue ribbon that’s slashed down the center by a white stripe, signifying selflessness.

The cross itself features a navy ship surrounded by a wreath. The president pinned it directly below my Trident. And he said again, “Marcus, I’m very proud of you. And I really like the SEALs.”

Again I thanked him. And then he saw me glance at his desk, and on it was the battle patch I’d asked Admiral Mullin to present to him. The president grinned and said, “Remember this?”

“Yessir.” Did I ever remember it. I’d hidden that baby in my Afghan trousers, just to make sure those Taliban bastards didn’t get it. And now here it was again, right on the desk of the president of the United States, the Lone Star of Texas, battle worn but still there.

We talked privately for a few minutes, and it was clear to me, President Bush knew all about the firefight on Murphy’s Ridge. And indeed how I had managed to get out of there.

At the end of our chat, I reached over and picked up the patch, just for old times’ sake. And the president suddenly said, in that rich Texan accent, “Now you put that down, boy! That doesn’t belong to you anymore.”

We both laughed, and he told me my former battle patch was going to his future museum. As I left the Oval Office he told me, “Anything you need, Marcus. That’s anything. You call me right here, on that phone, understand?”

“Yessir.” And it still felt to me like two Texans meeting for the first time. One of ’em kinda paternal, understanding. The other absolutely awestruck in the presence of a very great United States president, and my commander in chief.

Afterword

by Patrick Robinson

In the fall of 2006, Marcus Luttrell was redeployed with SEAL Team 5 in Iraq. At 0900 on Friday, October 6, thirty-six of them took off in a military Boeing C-17 from North Air Station, Coronado, bound for Ar Ramadi, the U.S. base which lies sixty miles west of Baghdad – a notorious trouble spot, of course. That’s why the SEALs were going.

The fact that the navy had deployed their wounded, decorated hero of the Afghan mountains was a considerable surprise to many people, most of whom thought he would leave SPECWARCOM for the less dangerous life of a civilian. Because even after more than a year, his back was still painful, his battered wrist was less than perfect, and he still suffered from that confounded Afghan stomach bug he had contracted from the Pepsi bottle.

But the deployment of Marcus Luttrell was a personal matter. He alone called the shots, not the navy. His contract with the SEALs still had many months to run, and there was no way he was going to quit. I think we mentioned, there ain’t no quit in him. Marcus wanted to stay, to fulfill his new obligations as leading petty officer (Alfa Platoon), a position which carries heavy responsibilities.

To me, he said, “I don’t want my guys to go without me. Because if anything happened to them and I wasn’t there, I guess I would not forgive myself.”

And so Marcus Luttrell went back to war. The C-17 was packed with all the worldly goods of SEAL Team 5, from machine guns to hand grenades. On board the flight was Petty Officer Morgan Luttrell (Bravo Platoon), a new posting not absolutely guaranteed to delight their mother.

Marcus had a new patch on his chest, identical to the one on the president’s desk in the Oval Office. “That’s who I’m fighting for, boy,” he told me. “My country, and the Lone Star State.”

The last words to me from this consummate Navy SEAL were “I’m outta here with my guys for a few months. God help the enemy, and God bless Texas.”