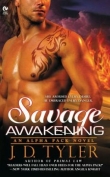

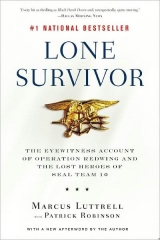

Текст книги "Lone survivor"

Автор книги: Marcus Luttrell

Жанры:

Военная история

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

Copyright © 2007 by Marcus Luttrell

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at www.HachetteBookGroup.com.

The Warner Books name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

First eBook Edition: June 2007

ISBN: 978-0-316-00754-2

Contents

Prologue

1: To Afghanistan...in a Flying Warehouse

2: Baby Seals...and Big Ole Gators

3: A School for Warriors

4: Welcome to Hell, Gentlemen

5: Like the Remnants of a Ravaged Army

6: ’Bye, Dudes, Give ’Em Hell

7: An Avalanche of Gunfire

8: The Final Battle for Murphy’s Ridge

9: Blown-up, Shot, and Presumed Dead

10: An American Fugitive Cornered by the Taliban

11: Reports of My Death Greatly Exaggerated

12: “Two-two-eight! It’s Two-two-eight!”

Epilogue: Lone Star

Afterword

Acknowledgments

Photo Insert

About the Authors

This book is dedicated to the memory of Murph, Axe, and Danny Boy, Kristensen, Shane, James, Senior, Jeff, Jacques, Taylor, and Mac. These were the eleven men of Alfa and Echo Platoons who fought and died in the mountains of Afghanistan trying to save my life, and with whom I was honored to serve my country. There is no waking hour when I do not remember them all with the deepest affection and the most profound, heartbreaking sadness.

Prologue

Would this ever become easier? House to house, freeway to freeway, state to state? Not so far. And here I was again, behind the wheel of a hired SUV, driving along another Main Street, past the shops and the gas station, this time in a windswept little town on Long Island, New York, South Shore, down by the long Atlantic beaches. Winter was coming. The skies were platinum. The whitecaps rolled in beneath dark, lowering clouds. So utterly appropriate, because this time was going to be worse than the others. A whole lot worse.

I found my landmark, the local post office, pulled in behind the building, and parked. We all stepped out of the vehicle, into a chill November day, the remains of the fall leaves swirling around our feet. No one wanted to lead the way, none of the five guys who accompanied me, and for a few moments we just stood there, like a group of mailmen on their break.

I knew where to go. The house was just a few yards down the street. And in a sense, I’d been there before – in Southern California, northern California, and Nevada. In the next few days, I still had to visit Washington and Virginia Beach. And so many things would always be precisely the same.

There would be the familiar devastated sadness, the kind of pain that wells up when young men are cut down in their prime. The same hollow feeling in each of the homes. The same uncontrollable tears. The same feeling of desolation, of brave people trying to be brave, lives which had uniformly been shot to pieces. Inconsolable. Sorrowful.

As before, I was the bearer of the terrible news, as if no one knew the truth until I arrived, so many weeks and months after so many funerals. And for me, this small gathering in Patchogue, Long Island, was going to be the worst.

I tried to get a hold of myself. But again in my mind I heard that terrible, terrible scream, the same one that awakens me, bullying its way into my solitary dreams, night after night, the confirmation of guilt. The endless guilt of the survivor.

“Help me, Marcus! Please help me!”

It was a desperate appeal in the mountains of a foreign land. It was a scream cried out in the echoing high canyons of one of the loneliest places on earth. It was the nearly unrecognizable cry of a mortally wounded creature. And it was a plea I could not answer. I can’t forget it. Because it was made by one of the finest people I ever met, a man who happened to be my best friend.

All the visits had been bad. Dan’s sister and wife, propping each other up; Eric’s father, an admiral, alone with his grief; James’s fiancée and father; Axe’s wife and family friends; Shane’s shattered mother in Las Vegas. They were all terrible. But this one would be worse.

I finally led the way through the blowing leaves, out into the cold, strange street, and along to the little house with its tiny garden, the grass uncut these days. But the lights of an illuminated American flag were still right there in the front window. They were the lights of a patriot, and they still shone defiantly, just as if he were still here. Mikey would have liked that.

We all stopped for a few moments, and then we climbed the little flight of steps and knocked on the door. She was pretty, the lady who answered the door, long dark hair, her eyes already brimming with tears. His mother.

She knew I had been the last person to see him alive. And she stared up at me with a look of such profound sadness it damn near broke me in half and said, quietly, “Thank you for coming.”

I somehow replied, “It’s because of your son that I am standing here.”

As we all walked inside, I looked straight at the hall table and on it was a large framed photograph of a man looking straight at me, half grinning. There was Mikey, all over again, and I could hear his mom saying, “He didn’t suffer, did he? Please tell me he didn’t suffer.”

I had to wipe the sleeve of my jacket across my eyes before I answered that. But I did answer. “No, Maureen. He didn’t. He died instantly.”

I had told her what she’d asked me to tell her. That kind of tactical response was turning out to be essential equipment for the lone survivor.

I tried to tell her of her son’s unbending courage, his will, his iron control. And as I’d come to expect, she seemed as if she had not yet accepted anything. Not until I related it. I was the essential bearer of the final bad news.

In the course of the next hour we tried to talk like adults. But it was too difficult. There was so much that could have been said, and so much that would never be said. And no amount of backup from my three buddies, plus the New York City fireman and policeman who accompanied us, made much difference.

But this was a journey I had to complete. I had promised myself I would do it, no matter what it took, because I knew what it would mean to each and every one of them. The sharing of personal anguish with someone who was there. House to house, grief to grief.

I considered it my sworn duty. But that did not make it any easier. Maureen hugged us all as we left. I nodded formally to the photograph of my best friend, and we walked down that sad little path to the street.

Tonight it would be just as bad, because we were going to see Heather, Mikey’s fiancée, in her downtown New York City apartment. It wasn’t fair. They would have been married by now. And the day after this, I had to go to Arlington National Cemetery to visit the graves of two more absent friends.

By any standards it was an expensive, long, and melancholy journey across the United States of America, paid for by the organization for which I work. Like me, like all of us, they understand. And as with many big corporations which have a dedicated workforce, you can tell a lot about them by their corporate philosophy, their written constitution, if you like.

It’s the piece of writing which defines their employees and their standards. I have for several years tried to base my life on the opening paragraph:

“In times of uncertainty there is a special breed of warrior ready to answer our Nation’s call; a common man with uncommon desire to succeed. Forged by adversity, he stands alongside America’s finest special operations forces to serve his country and the American people, and to protect their way of life. I am that man.”

My name is Marcus. Marcus Luttrell. I’m a United States Navy SEAL, Team Leader, SDV Team 1, Alfa Platoon. Like every other SEAL, I’m trained in weapons, demolition, and unarmed combat. I’m a sniper, and I’m the platoon medic. But most of all, I’m an American. And when the bell sounds, I will come out fighting for my country and for my teammates. If necessary, to the death.

And that’s not just because the SEALs trained me to do so; it’s because I’m willing to do so. I’m a patriot, and I fight with the Lone Star of Texas on my right arm and another Texas flag over my heart. For me, defeat is unthinkable.

Mikey died in the summer of 2005, fighting shoulder to shoulder with me in the high country of northeast Afghanistan. He was the best officer I ever knew, an iron-souled warrior of colossal, almost unbelievable courage in the face of the enemy.

Two who would believe it were my other buddies who also fought and died up there. That’s Danny and Axe: two American heroes, two towering figures in a fighting force where valor is a common virtue. Their lives stand as a testimony to the central paragraph of the philosophy of the U.S. Navy SEALs:

“I will never quit. I persevere and thrive on adversity. My Nation expects me to be physically harder and mentally stronger than my enemies. If knocked down, I will get back up, every time. I will draw on every remaining ounce of strength to protect my teammates and to accomplish our mission. I am never out of the fight.”

As I mentioned, my name is Marcus. And I’m writing this book because of my three buddies Mikey, Danny, and Axe. If I don’t write it, no one will ever understand the indomitable courage under fire of those three Americans. And that would be the biggest tragedy of all.

1

To Afghanistan...

in a Flying Warehouse

This was payback time for the World Trade Center. We were coming after the guys who did it. If not the actual guys, then their blood brothers, the lunatics who still wished us dead and might try it again.

Good-byes tend to be curt among Navy SEALs. A quick backslap, a friendly bear hug, no one uttering what we’re all thinking: Here we go again, guys, going to war, to another trouble spot, another half-assed enemy willing to try their luck against us...they must be out of their minds.

It’s a SEAL thing, our unspoken invincibility, the silent code of the elite warriors of the U.S. Armed Forces. Big, fast, highly trained guys, armed to the teeth, expert in unarmed combat, so stealthy no one ever hears us coming. SEALs are masters of strategy, professional marksmen with rifles, artists with machine guns, and, if necessary, pretty handy with knives. In general terms, we believe there are very few of the world’s problems we could not solve with high explosive or a well-aimed bullet.

We operate on sea, air, and land. That’s where we got our name. U.S. Navy SEALs, underwater, on the water, or out of the water. Man, we can do it all. And where we were going, it was likely to be strictly out of the water. Way out of the water. Ten thousand feet up some treeless moonscape of a mountain range in one of the loneliest and sometimes most lawless places in the world. Afghanistan.

“ ’Bye, Marcus.” “Good luck, Mikey.” “Take it easy, Matt.” “See you later, guys.” I remember it like it was yesterday, someone pulling open the door to our barracks room, the light spilling out into the warm, dark night of Bahrain, this strange desert kingdom, which is joined to Saudi Arabia by the two-mile-long King Fahd Causeway.

The six of us, dressed in our light combat gear – flat desert khakis with Oakley assault boots – stepped outside into a light, warm breeze. It was March 2005, not yet hotter than hell, like it is in summer. But still unusually warm for a group of Americans in springtime, even for a Texan like me. Bahrain stands on the 26° north line of latitude. That’s more than four hundred miles to the south of Baghdad, and that’s hot.

Our particular unit was situated on the south side of the capital city of Manama, way up in the northeast corner of the island. This meant we had to be transported right through the middle of town to the U.S. air base on Muharraq Island for all flights to and from Bahrain. We didn’t mind this, but we didn’t love it either.

That little journey, maybe five miles, took us through a city that felt much as we did. The locals didn’t love us either. There was a kind of sullen look to them, as if they were sick to death of having the American military around them. In fact, there were districts in Manama known as black flag areas, where tradesmen, shopkeepers, and private citizens hung black flags outside their properties to signify Americans are not welcome.

I guess it wasn’t quite as vicious as Juden Verboten was in Hitler’s Germany. But there are undercurrents of hatred all over the Arab world, and we knew there were many sympathizers with the Muslim extremist fanatics of the Taliban and al Qaeda. The black flags worked. We stayed well clear of those places.

Nonetheless we had to drive through the city in an unprotected vehicle over another causeway, the Sheik Hamad, named for the emir. They’re big on causeways, and I guess they will build more, since there are thirty-two other much smaller islands forming the low-lying Bahrainian archipelago, right off the Saudi western shore, in the Gulf of Iran.

Anyway, we drove on through Manama out to Muharraq, where the U.S. air base lies to the south of the main Bahrain International Airport. Awaiting us was the huge C-130 Hercules, a giant turbo-prop freighter. It’s one of the noisiest aircraft in the stratosphere, a big, echoing, steel cave specifically designed to carry heavy-duty freight – not sensitive, delicate, poetic conversationalists such as ourselves.

We loaded and stowed our essential equipment: heavy weaps (machine guns), M4 rifles, SIG-Sauer 9mm pistols, pigstickers (combat knives), ammunition belts, grenades, medical and communication gear. A couple of the guys slung up hammocks made of thick netting. The rest of us settled back into seats that were also made of netting. Business class this wasn’t. But frogs don’t travel light, and they don’t expect comfort. That’s frogmen, by the way, which we all were.

Stuck here in this flying warehouse, this utterly primitive form of passenger transportation, there was a certain amount of cheerful griping and moaning. But if the six of us were inserted into some hellhole of a battleground, soaking wet, freezing cold, wounded, trapped, outnumbered, fighting for our lives, you would not hear one solitary word of complaint. That’s the way of our brotherhood. It’s a strictly American brotherhood, mostly forged in blood. Hard-won, unbreakable. Built on a shared patriotism, shared courage, and shared trust in one another. There is no fighting force in the world quite like us.

The flight crew checked we were all strapped in, and then those thunderous Boeing engines roared. Jesus, the noise was unbelievable. I might just as well have been sitting in the gearbox. The whole aircraft shook and rumbled as we charged down the runway, taking off to the southwest, directly into the desert wind which gusted out of the mainland Arabian peninsula. There were no other passengers on board, just the flight crew and, in the rear, us, headed out to do God’s work on behalf of the U.S. government and our commander in chief, President George W. Bush. In a sense, we were all alone. As usual.

We banked out over the Gulf of Bahrain and made a long, left-hand swing onto our easterly course. It would have been a whole hell of a lot quicker to head directly northeast across the gulf. But that would have taken us over the dubious southern uplands of the Islamic Republic of Iran, and we do not do that.

Instead we stayed south, flying high over the friendly coastal deserts of the United Arab Emirates, north of the burning sands of the Rub al Khali, the Empty Quarter. Astern of us lay the fevered cauldrons of loathing in Iraq and nearby Kuwait, places where I had previously served. Below us were the more friendly, enlightened desert kingdoms of the world’s coming natural-gas capital, Qatar; the oil-sodden emirate of Abu Dhabi; the gleaming modern high-rises of Dubai; and then, farther east, the craggy coastline of Oman.

None of us were especially sad to leave Bahrain, which was the first place in the Middle East where oil was discovered. It had its history, and we often had fun in the local markets bargaining with local merchants for everything. But we never felt at home there, and somehow as we climbed into the dark skies, we felt we were leaving behind all that was god-awful in the northern reaches of the gulf and embarking on a brand-new mission, one that we understood.

In Baghdad we were up against an enemy we often could not see and were obliged to get out there and find. And when we found him, we scarcely knew who he was – al Qaeda or Taliban, Shiite or Sunni, Iraqi or foreign, a freedom fighter for Saddam or an insurgent fighting for some kind of a different god from our own, a god who somehow sanctioned murder of innocent civilians, a god who’d effectively booted the Ten Commandments over the touchline and out of play.

They were ever present, ever dangerous, giving us a clear pattern of total confusion, if you know what I mean. Somehow, shifting positions in the big Hercules freighter, we were leaving behind a place which was systematically tearing itself apart and heading for a place full of wild mountain men who were hell-bent on tearing us apart.

Afghanistan. This was very different. Those mountains up in the northeast, the western end of the mighty range of the Hindu Kush, were the very same mountains where the Taliban had sheltered the lunatics of al Qaeda, shielded the crazed followers of Osama bin Laden while they plotted the attacks on the World Trade Center in New York on 9/11.

This was where bin Laden’s fighters found a home training base. Let’s face it, al Qaeda means “the base,” and in return for the Saudi fanatic bin Laden’s money, the Taliban made it all possible. Right now these very same guys, the remnants of the Taliban and the last few tribal warriors of al Qaeda, were preparing to start over, trying to fight their way through the mountain passes, intent on setting up new training camps and military headquarters and, eventually, their own government in place of the democratically elected one.

They may not have been the precise same guys who planned 9/11. But they were most certainly their descendants, their heirs, their followers. They were part of the same crowd who knocked down the North and South towers in the Big Apple on the infamous Tuesday morning in 2001. And our coming task was to stop them, right there in those mountains, by whatever means necessary.

Thus far, those mountain men had been kicking some serious ass in their skirmishes with our military. Which was more or less why the brass had sent for us. When things get very rough, they usually send for us. That’s why the navy spends years training SEAL teams in Coronado, California, and Virginia Beach. Especially for times like these, when Uncle Sam’s velvet glove makes way for the iron fist of SPECWARCOM (that’s Special Forces Command).

And that was why all of us were here. Our mission may have been strategic, it may have been secret. However, one point was crystalline clear, at least to the six SEALs in that rumbling Hercules high above the Arabian desert. This was payback time for the World Trade Center. We were coming after the guys who did it. If not the actual guys, then their blood brothers, the lunatics who still wished us dead and might try it again. Same thing, right?

We knew what we were coming for. And we knew where we were going: right up there to the high peaks of the Hindu Kush, those same mountains where bin Laden might still be and where his new bands of disciples were still hiding. Somewhere.

The pure clarity of purpose was inspirational to us. Gone were the treacherous, dusty backstreets of Baghdad, where even children of three and four were taught to hate us. Dead ahead, in Afghanistan, awaited an ancient battleground where we could match our enemy, strength for strength, stealth for stealth, steel for steel.

This might be, perhaps, a little daunting for regular soldiers. But not for SEALs. And I can state with absolute certainty that all six of us were excited by the prospect, looking forward to doing our job out there in the open, confident of our ultimate success, sure of our training, experience, and judgment. You see, we’re invincible. That’s what they taught us. That’s what we believe.

It’s written right there in black and white in the official philosophy of the U.S. Navy SEAL, the last two paragraphs of which read:

We train for war and fight to win. I stand ready to bring the full spectrum of combat power to bear in order to achieve my mission and the goals established by my country. The execution of my duties will be swift and violent when required, yet guided by the very principles I serve to defend.

Brave men have fought and died building the proud tradition and feared reputation that I am bound to uphold. In the worst of conditions, the legacy of my teammates steadies my resolve and silently guides my every deed. I will not fail.

Each one of us had grown a beard in order to look more like Afghan fighters. It was important for us to appear nonmilitary, to not stand out in a crowd. Despite this, I can guarantee you that if three SEALs were put into a crowded airport, I would spot them all, just by their bearing, their confidence, their obvious discipline, the way they walk. I’m not saying anyone else could recognize them. But I most certainly could.

The guys who traveled from Bahrain with me were remarkably diverse, even by SEAL standards. There was SGT2 Matthew Gene Axelson, not yet thirty, a petty officer from California, married to Cindy, devoted to her and to his parents, Cordell and Donna, and to his brother, Jeff.

I always called him Axe, and I knew him well. My twin brother, Morgan, was his best friend. He’d been to our home in Texas, and he and I had been together for a long time in SEAL Delivery Vehicle Team 1, Alfa Platoon. He and Morgan were swim buddies together in SEAL training, went through Sniper School together.

Axe was a quiet man, six foot four, with piercing blue eyes and curly hair. He was smart and the best Trivial Pursuit player I ever saw. I loved talking to him because of how much he knew. He would come out with answers that would have defied the learning of a Harvard professor. Places, countries, their populations, principal industries.

In the teams, he was always professional. I never once saw him upset, and he always knew precisely what he was doing. He was just one of those guys. What was difficult and confusing for others was usually a piece of cake for him. In combat he was a supreme athlete, swift, violent, brutal if necessary. His family never knew that side of him. They saw only the calm, cheerful navy man who could undoubtedly have been a professional golfer, a guy who loved a laugh and a cold beer.

You could hardly meet a better person. He was an incredible man.

Then there was my best friend, Lieutenant Michael Patrick Murphy, also not yet thirty, an honors graduate from Penn State, a hockey player, accepted by several law schools before he turned the rudder hard over and changed course for the United States Navy. Mikey was an inveterate reader. His favorite book was Steven Pressfield’s Gates of Fire, the story of the immortal stand of the Spartans at Thermopylae.

He was vastly experienced in the Middle East, having served in Jordan, Qatar, and Djibouti on the Horn of Africa. We started our careers as SEALs at the same time, and we were probably flung together by a shared devotion to the smart-ass remark. Also, neither of us could sleep if we were under the slightest pressure. Our insomnia was shared like our humor. We used to hang out together half the night, and I can truthfully say no one ever made me laugh like that.

I was always razzing him about being dirty. We’d sometimes go out on patrol every day for weeks, and there seems to be no time to shower and no point in showering when you’re likely to be up to your armpits in swamp water a few hours later. Here’s a typical exchange between us, petty officer team leader to commissioned SEAL officer:

“Mikey, you smell like shit, for Christ’s sake. Why the hell don’t you take a shower?”

“Right away, Marcus. Remind me to do that tomorrow, willya?”

“Roger that, sir!”

For his nearest and dearest, he used a particularly large gift shop, otherwise known as the U.S. highway system. I remember him giving his very beautiful girlfriend Heather a gift-wrapped traffic cone for her birthday. For Christmas, he gave her one of those flashing red lights which fit on top of those cones at night. Gift-wrapped, of course. He once gave me a stop sign for my birthday.

And you should have seen his traveling bag. It was enormous, a big, cavernous hockey duffel bag, the kind carried by his favorite team, the New York Rangers. The single heaviest piece of luggage in the entire navy. But it didn’t sport the Rangers logo. On its top were two simple words: Piss off.

There was no situation for which he could not summon a really smart-ass remark. Mikey was once involved in a terrible and almost fatal accident, and one of the guys asked him to explain what happened.

“C’mon,” said the New York lieutenant, as if it were a subject of which he was profoundly weary. “You’re always bringing up that old shit. Fuggeddaboutit.”

The actual accident had happened just two days earlier.

He was also the finest officer I ever met, a natural leader, a really terrific SEAL who never, ever bossed anyone around. It was always Please. Always Would you mind? Never Do that, do this. And he simply would not tolerate any other high-ranking officer, commissioned or noncommissioned, reaming out one of his guys.

He insisted the buck stopped with him. He always took the hit himself. If a reprimand was due, he accepted the blame. But don’t even try to go around him and bawl out one of his guys, because he could be a formidable adversary when riled. And that riled him.

He was excellent underwater, and a powerful swimmer. Trouble was, he was a bit slow, and that was truly his only flaw. One time, he and I were on a two-mile training swim, and when I finally hit the beach I couldn’t find him. Finally I saw him splashing through the water about four hundred yards offshore. Christ, he’s in trouble – that was my first thought.

So I charged back into the freezing sea and set out to rescue him. I’m not a real fast runner, but I’m quick through the water, and I reached him with no trouble. I should have known better.

“Get away from me, Marcus!” he yelled. “I’m a race car in the red, highest revs on the TAC. Don’t mess with me, Marcus, not now. You’re dealing with a race car here.”

Only Mike Murphy. If I told that story to any SEAL in our platoon, withheld the name, and then asked who said it, everyone would guess Mikey.

Sitting opposite me in the Hercules was Senior Chief Daniel Richard Healy, another awesome Navy SEAL, six foot three, thirty-seven, married to Norminda, father of seven children. He was born in New Hampshire and joined the navy in 1990, advancing to serve in the SEAL teams and learning near-fluent Russian.

Danny and I served in the same team, SDV Team 1, for three years. He was a little older than most of us and referred to us as his kids – as if he didn’t have enough. And he loved us all with equal passion, both big families, his wife and children, sisters, brothers, and parents, and the even bigger one hitherto based on the island of Bahrain. Dan was worse than Mikey in his defense of his SEALs. No one ever dared yell at any of us while he was around.

He guarded his flock assiduously, researched every mission with complete thoroughness, gathered the intel, checked the maps, charts, photographs, all reconnaissance. Also, he paid attention to the upcoming missions and made sure his kids were always in the front line. That’s the place we were trained for, the place we liked to go.

In many ways Dan was tough on everyone. There were times when he and I did not see eye to eye. He was unfailingly certain that his way was the best way, mostly the only way. But his heart was in the right place at all times. Dan Healy was one hell of a Navy SEAL, a role model for everything a senior chief should be, an iron man who became a strategist and who knew his job from A to Z. I talked face to face with big Dan almost every day of my life.

Somewhere up above us, swinging in his hammock, headset on, listening to rock-and-roll music, was Petty Officer Second Class Shane Patton, twenty-two-year-old surfer and skateboarder originally from Las Vegas, Nevada. My protégé. As the primary communications operator, I had Shane as my number two. Like a much younger Mike Murphy, he too was a virtuoso at the smart-ass remark and, as you would expect, an outstanding frogman.

It was hard for me to identify with Shane because he was so different. I once walked into the comms center, and he was trying to order a leopard-skin coat on the Internet.

“What the hell do you want that for?” I asked.

“It’s just so cool, man,” he replied, terminating further discussion.

A big, robust guy with blond hair and a relatively insolent grin, Shane was supersmart. I never had to tell him anything. He knew what to do at all times. At first, this slightly irritated me; you know, telling a much junior guy what you want done, and it turns out he’s already done it. Every time. Took me a while to get used to the fact I had an assistant who was damn near as sharp as Matt Axelson. And that’s as sharp as it gets.

Shane, like a lot of those beach gods, was hugely laid back. His buddies would probably call it supercool or some such word. But in a comms operator, that quality is damn near priceless. If there’s a firefight going on, and Shane’s back at HQ manning the radio, you’re listening to one ultracalm, very measured SEAL communicator. Sorry, I meant dude. That was an all-purpose word for Shane. Even I was a dude, according to him. Even the president of the United States was a dude, according to him. Actually he accorded President Bush the highest accolade, the gold-plated Congressional Medal of Honor awarded by the surf gods: He’s a real dude, man, a real dude.