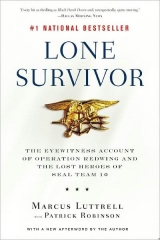

Текст книги "Lone survivor"

Автор книги: Marcus Luttrell

Жанры:

Военная история

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

9

Blown-up, Shot,

and Presumed Dead

Right behind me I heard the soft footsteps of the chasing gunmen...there were two of them, just above me in the rocks. Searching. I had only split seconds to work, because they were both on me, AKs raised...I went for my grenades.

Even in the pitch black of the night, I could feel the shadow of the mountain looming above me. I actually thought I could see it, a kind of dark force, darker than everything else, blacker than the rock walls upon which I was leaning.

I knew it was a hell of a long way to the top, and I would have to move sideways like a delta crab if I was going to make it. It was also going to take me all night, but somehow I had to get up there, all the way to the top.

I had two prime reasons for my strategy. First, it would be flat up there, so if it came down to another firefight, I would have a good chance. No guys firing down on me. Every SEAL likes his chances of winning a fight on flat ground.

The second issue was calling in help. No helicopter ever built could land safely on these steep Afghan cliffs. The only place within the mountain range where an MH-47 could put down was in the flat bowl of the fields below, where the villagers raised crops. Dope, that is.

And there was no way I was going to risk hanging out near a village. I was going up, to the upper flatlands, where a helo could get in and then get out. Also, my radio reception would be better up there. I could only hope the Americans were still scouring the mountains, looking for the missing Redwings.

Meanwhile, I thought I might be dying of thirst, and my parched throat was driving me onward to water and perhaps safety. So I took my first steps, guessing I was probably going to climb around five hundred feet straight up. But I’d travel a whole lot farther on the zigzag course I’d have to make up the mountain.

I began my climb, out there in the dark, by moving directly upward. I jammed my rifle into my belt so I had two hands to grip, but before I’d made the first twenty feet going slightly right, I slipped badly, which was a very scary experience. The gradient was almost sheer, straight down to the valley floor.

In my condition I probably would not have survived the fall, and I somehow saved myself from falling any more than about ten feet. Then I picked it up again, clawing my way up, facing the mountain and grabbing hold of anything I could with a grip like a mechanical digger. You’d have needed a chain saw to pry me off that cliff face. All I knew was, if I fell, I’d probably plummet several hundred feet to my death. Which was good for the concentration.

So I kept going, climbing mostly sideways, grabbing rocks, vines, or branches, anything for a grip. Every now and then I’d dislodge something or snap a branch that would not bear my weight. And I guess I must have made more noise than the Taliban army has ever made in mountain maneuvers.

I’d been going for a couple of hours when I sensed I heard something behind me. I say sensed because when you are operating in absolute darkness, with no sight at all, everything else is heightened, all of your senses, particularly sound and smell. Not to mention the sixth one, same one a goat or an antelope or a zebra has, the one that warns vulnerable grazing animals of the presence of a predator.

Now, I wasn’t that vulnerable. And I sure as hell wasn’t grazing. But right then I was in Predator Central. Those cutthroat tribal bastards were all over my case and, for all I knew, closing in on me.

I lay flat, stock-still on the mountain. And then I heard it again, the distinct snap of a twig or a branch. I estimated it was maybe two hundred yards behind me. Right then my hearing was at some kind of a peak in this ultraquiet high country. I could have picked up the soft fart of a billy goat a mile away.

Then I heard it once more. Not the billy goat, the twig. And I knew for absolute certain I was being followed. Fuck! There was still no moon, and I could still see nothing. But that would not be true of the Taliban. They’d been stealing equipment from the Russians, and then the Americans, for years. Everything they had was stolen, except for what bin Laden had purchased for them. And their supplies certainly included a few pairs of NVGs. The Russians were, after all, pioneers of that particular piece of battle gear, and we knew the mujahideen had stolen everything from them when the Soviet army finally pulled out.

The presence of an unseen Afghani tracker was very bad news for me, not least for the remnants of my morale. The thought that there was a group of killers out there, stalking me across this mountain, able to see me when I could not see them...well, that was a sonofabitch in any man’s army.

I decided to press on and hope they did not decide to open fire. When I reached the top, I’d take them out. Just as soon as I could see the little bastards. First sign of light, I’d stake my position underneath some bushes where no one could see me, and then I’d deal with them as soon as they got within range. Meantime, I was so thirsty I thought I might die before that hour approached.

I was trying everything. I was breaking the thinnest tree branches off and sucking at them for liquid. I sucked at the grass when I found some, hoping for a few drops of mountain dew. I even tried to wring out my socks to find just a taste of water. There is nothing quite so terrible as dying of thirst. Believe me. I’ve been there.

As the night wore on, I began to hear the occasional U.S. military aircraft above the mountains, usually flying high. And when I heard one in time, I was out there whirling my buzz-saw lights, transmitting the beacon as well as I could, still a walking distress signal. But no one heard me. It occurred to me that no one believed I was alive. And that was a very grim thought. It would be pretty hard to find me up here, even if the entire Bagram base was searching for me in these endless mountains. But if no one believed I was still breathing, well, that was probably the end for me. I experienced an inevitable feeling of utter desolation. Worse yet, I was so weakened, and in such pain, I realized, once and for all, I was never going to make it to the top of the mountain. Actually, I might have made it, but my left leg, blasted by that RPG, was never going to stand the climb. I would just have to keep going sideways, struggling across the steep face of the mountain, sometimes down, sometimes up, and hope to get my chance.

I was still losing blood, and I still could not speak. But I could hear, and I could hear my pursuers, sometimes calling to each other. I remember thinking this was very strange because they normally moved around in total silence. Remember those goatherds? I never heard that first one coming until he was about four feet from me. That’s just the way they are, treading softly, lean, light men with no encumbrances – not even water.

When those Afghans travel, they carry their guns and ammunition and nothing else. One guy carries the water for everyone; another hauls the extra ammunition. And this leaves the main force free to move very fast, very softly. They are born trackers, able to pick up a trail across the roughest ground, and they can walk right up on you.

Of course, that assumes they are only after one of their own. Trying to follow a great 230-pound hulk like myself, slipping and sliding, crashing and breaking branches, causing minor avalanches on the loose ground – I must have been an Afghan tracker’s dream. Even I realized my chance of actually losing them was close to zero.

Maybe those calls I heard among them were not really commands. Maybe they were outbursts of suppressed laughter at my truly horrible rock-climbing abilities. Wait until it gets light, I thought. This playing field would even out real quick. That’s if they didn’t shoot me first, in the dark.

I kept skirting around the mountain. Way below I could see the lights from a couple of lanterns, and I thought I could see the flickering flame of a fire. That must have been the valley floor, and it gave me my first guidance as to the terrain, but not much. In fact, it gave me the impression the ground where I was standing was flat, which it really was not. I stopped for a minute to see if there was anything else down in that valley, any further sign of my enemy, but I could still see just about nothing except for the lanterns and the fire, all of them about a mile down.

I gathered myself and took a step forward. And in that split second I realized I had stepped into the void. I just fell clean off that mountain, straight down, falling through the air, not over the ground. I hit the side of the mountain with a terrific bang, knocked the breath right out of me. Then I rolled, crashing through a copse of trees, trying to grab something to slow me down.

But I was moving too fast, and gathering speed. I fell helplessly down a steep bit, which leveled out for a few yards and allowed me to slow down. Finally I stopped on the edge of yet another precipice, which I sensed rather than saw. And I just lay there gasping for breath for a good twenty minutes, scared to death I’d find myself paralyzed.

But I wasn’t. I could stand. I still had my rifle, although my strobe light had gone. And somehow I had to get back up to my highest point. The lower I was positioned down this mountain, the less my chance of getting rescued. I must go upward, and so I set off again.

I climbed, slipped, and scrambled for two more hours, until I thought I was more or less back to the point where I’d fallen off the mountain. It was 0200 now, and I’d been going for a long time, maybe six or seven hours. The pain was becoming diabolical, but in a way I was relieved I still had feeling in that left leg.

The Taliban army was still following me. I heard them, louder as I climbed higher, as if they’d been waiting for me. They were certainly a bigger force now than they had been two hours ago. I could hear them all around, more and more people searching for me, dogs barking, maybe a half mile back.

By now I could hear the river, which I knew was the same one I’d fallen in the previous afternoon. The same river on whose banks my three buddies lay dead. Thirsty as I was, I could not bring myself to go in search of its ice-cold flowing waters gushing down the mountainside. That was the only water on this earth I could not drink, water from the river which flowed right by the bodies of Mikey, Danny, and Axe. I had to find a different one.

With no compass, only my watch, I had to revert to navigation by the stars, which mercifully were now out, the thick high banks of clouds having passed over. I found the Big Dipper and followed the long curve of its stars all the way to the right angle at the end, where the shape angles upward, pointing directly at the polestar. That’s the North Star. We learned it in BUD/S.

If I turned directly toward it and held out my left arm at a right angle, that way was west, the way I was headed. I think at this point I may have been suffering from hallucinations, that very odd sensation when you cannot really tell reality from a dream.

Like most SEALs, I’d experienced it before, at the back end of Hell Week. But right now I was becoming very light-headed. I was a hunted animal all alone in wild country, and I tried to pretend my buddies were still alive. I invented some kind of a formation with Danny climbing out on my right flank, Axe up to the left, and Mikey calling the shots in the rear.

I pretended they were there, I just couldn’t see them. I think I was reaching the end of my tether. But I kept reminding myself of Hell Week. I kept telling myself this was just Hell Week all over again; I’d sucked it up then, and I could suck it up now. Whatever these bastards threw at me, I could take it. I’d come through. I might have been losing my marbles, but I was still a SEAL.

I could not, however, deny the fact I was also becoming disheartened. For the moment my pursuers were quiet, and I suddenly came upon a huge tree with a couple of big logs resting directly underneath it. I crawled under one of them and rested for a while, just lying there, feeling damned sorry for myself.

In my head I played over and over again one of the verses of Toby Keith’s country and western classic “American Soldier.” I remember lying there quietly singing the words to myself, the part that said I might have to die...“I’ll bear that cross with honor.”

I sang those words all night. I can’t tell you how much they meant to me. I can tell you, it’s little things like that, the words of a song, which can give you the strength to go on. Nonetheless, the fact was I had no idea what to do.

It occurred to me I could just settle in right here and make it my last stand. But I quickly dismissed this as a strategy. In my mind I was still committed to Axe’s last request: “You stay alive, Marcus. And tell Cindy I love her.” Helluva lot of good it would do Cindy Axelson if I ended up shot to pieces on the slopes of this godforsaken mountain. And who then would ever know what my buddies had done? And how hard and bravely they had fought? No. It was all up to me. I had to get out and tell our story.

I was comfortable and very, very tired, but thirst drove me on. Screw this, I decided, and I dragged myself up again and kept walking, hobbling, that is, making the most of this apparent expanse of flatter ground. It was just beginning to get light, around 0600. I knew that six hours from now, the sun would be in the south, but it was such a high sun out here, almost directly overhead, and it made navigation that much more difficult. I remember wondering where the hell I would be next time I saw the friendly polestar.

Almost immediately I found myself on a trail which was going my way. I could tell by the tight feel of the ground it was pretty well used, which meant I would have to move with immense care. Trails frequently traveled invariably lead to people, and before long I saw a house up ahead, maybe even three or four. At this distance it was hard to tell.

My first thought was of a tap or a well. If I had to, I’d get into one of these primitive residences and get rid of the occupants somehow. Then I could clean up my wounds and drink. But as I grew closer I could see there were four houses, very close together. To get their water I’d probably have to kill twenty people, and that was too much for me. I elected to keep going, praying I’d stumble upon a river or a mountain stream before much longer.

Well, I didn’t. The sun was up, and it was growing hotter. I kept going for another four or five hours, and the hallucinations were getting worse. I kept wanting to ask Mikey what we should do. My mouth and throat had just about seized up. I could barely move my parched tongue, which was now firmly stuck to the roof of my mouth. I was afraid if I tried to move it, it would tear the skin off. I cannot describe the feeling. I had to get water.

Every bone in my body was crying out for rest, but I knew if I stopped, and perhaps slept, I would die. I had to keep going. It was strange, but the thirst which was killing me was also the driving force keeping me on this long, desperate march.

I recall thinking there was no water this high up, and I resolved to go back down to slightly lower slopes where hopefully a stream might come cascading out of the rocks, the way it does up here. Right then the sun was burning down on me, really hot, and way above me, the high peaks were still snowcapped. Something had to be melting, for Christ’s sake. And all that water had to be going somewhere. I just had to find it.

Down in these lower areas, I found myself in the most beautiful green forest, so beautiful I wondered whether it might be a mirage. There were soft ferns, deep green grasses, and tall shady evergreens, a scene of verdant, lush mountain growth. Jesus Christ, there had to be water down here somewhere.

I paused often, listening intently for the sound of a running stream. But there was only silence, that shattering, merciless silence of the high country where no roads carve into the landscape, where no machines disrupt and pollute the air. Where there are no automobiles or tractors; no television, radio, or even electricity. Nothing. Just nature, the way it’s been for thousands of years up here in this land of truly terrible beauty and ravenous hatred.

Don’t get me wrong. The gradients were still very steep, and I was working my way through the forest, through the gutters of the mountain. Much of the time I was just crawling, hands and knees, trying to ease the pain in my left leg. To be honest, I really thought I might be finished now. I was full of despair, wondering if I might black out, begging my God to help me.

Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death,

I will fear no evil: For Thou art with me; Thy rod and Thy staff they comfort me . . .

That’s the Twenty-third Psalm, of course. We think of it as the Psalm of the SEALs. It is repeated at all of our religious ser-vices, all funerals. Too many funerals. I know it by heart. And I clung to its message, that even in death I would not be abandoned.

Thou preparest a table before me in the presence of mine enemies: Thou anointest my head with oil; my cup runneth over.

Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life: and I will dwell in the house of the Lord for ever.

It was all I had, just a plaintive cry to a God Who was with me, but Whose ways were becoming unclear to me. I had been saved from more or less certain death, and I was still armed with my rifle. But I did not know what to do anymore, except keep trying.

I left the trail and once more went upward, heading for high ground again. I was listening, straining to hear the sound of the water I knew must be here somewhere. I was on a steep escarpment, hanging on to a tree with my right hand, leaning out away from the cliff face. Would I ever hear the tumbling sound of a mountain stream, or was I really destined to die of thirst up here where no American would ever find me?

I kept repeating the Twenty-third Psalm in my head, over and over, trying to stop myself from breaking down. I was scared, freezing cold, without shelter or proper clothes, and I just kept saying it . . .

The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want.

He maketh me to lie down in green pastures: He leadeth me beside the still waters.

He restoreth my soul: He leadeth me in the paths of righteousness for His name’s sake . . .

That’s how far I was in the prayer when I heard the water for the first time. I could not believe it. There it was, unmistakable, way below me, a brook, maybe even a small waterfall. In this pure mountain air, amid this awesome silence, that was swiftly flowing water. I had to find a way down to it.

I guess I knew in that moment, I was not going to die of thirst, whatever else befell me. It was just one of those moments that make your life spin right out in front of you. I thought of home, and my mom and my dad, and my brothers and friends. Did any of them know about me? And what had happened? Maybe they thought I was dead. Maybe someone had told them I was dead. And in those fleeting seconds I was overwhelmed by the sadness, the heartbreaking, crushing sadness of what this would mean to my mom, the lady who always told me I was Mama’s angel.

What I did not know at the time but learned later was that everyone thought I was dead. Back home it was now some time in the small hours of Wednesday morning, June 29, and several hours previously a television station had announced that a four-man SEAL reconnaissance team that was on a mission in the northeast mountains of Afghanistan had all been killed in action. My name was among the four.

The station, like the rest of the world’s media, had also announced the loss of the MH-47 helicopter with everyone on board, eight SEALs and eight members of the 160th SOAR Night Stalkers. Which made twenty special forces dead, the worst special ops catastrophe ever. My mom collapsed.

By the middle part of that Tuesday evening, people had begun to arrive at the ranch, local people, our friends, people who wanted to be with my mom and dad, just in case there was anything they could do to help. They arrived in trucks, cars, SUVs, and on motorbikes, a steady stream of families who all said damn near the same thing: We just want to be with you.

Outside the door of the main house, the front yard was like a parking lot. By midnight there were seventy-five people in attendance, including Eric and Aaron Rooney, from the family that owns one of the big East Texas construction corporations; David and Michael Thornberry, local land, cattle, and oil people, with their father, Jonathon; Slim, Kevin, Kyle, and Wade Albright, my boyhood friends, a lot of them Aggies.

There was Joe Lord; Andy Magee; Cheeser; Big Roon; my brother Opie and our buddy Sean; Tray Baker; Larry Firmin; Richard Tanner; Benny Wiley; the strength coach at Texas Tech in Lubbock. Those big tough guys were all in grade school with me.

Another of our local construction moguls, Scott Whitehead, showed up. He never even knew us, but he wanted to be there. He turned out to be a tower of strength for my mom, still calls her every day. Master Sergeant Daniel, highly decorated U.S. Army, showed up in full uniform, knocked on the front door, and told my dad he wanted to help in any way he could. He still shows up nearly every day, just to make sure Mom’s okay.

And of course there was my twin brother, Morgan, making all speed to the ranch, refusing point-blank to accept the broadcaster’s “fact” that I was dead. My other brother Scottie got there first, but not being an identical twin brother to me, he could only know what he was told, not what the telepathic wavelengths told him. He was almost as devastated as Mom.

My dad hit the Internet to check if there was further news or any official announcement from the SEAL HQ in Hawaii, my home base. All he found was confirmation of the MH-47 crash and four other SEALs missing in action. However, one of the Hawaiian newspapers was reporting the death of all four of us. At which moment I guess he believed it was true.

Shortly after 2:00 a.m. in Texas, the SEALs began to arrive at the ranch from Coronado. Lieutenant John Jones (JJ) in company with Chief Chris Gothro flew in, with Bosun’s Mate Teg Gill, one of the strongest men I know. Lieutenant David Duf-field arrived from Coronado right afterward, with John Owens and Jeremy Franklin. Lieutenant Josh Wynn and Lieutenant Nathan Shoemaker came in from Virginia Beach. Gunner’s Mate First Class Justin Pitman made the journey from Florida. I should stress that none of this was planned or orchestrated. They just came, strangers mingling with friends, united, I suppose, in grief for a lost brother.

And there to greet them all with my mom and dad was the mighty figure of Billy Shelton. No one had ever seen him in tears before. It’s often that way with the toughest of men.

Chief Gothro immediately told my parents he did not give a damn what the media said. There was no confirmation that any of the original four-man SEAL team was dead, although it was highly likely they had not all survived. He knew about Mikey’s last call: My guys are dying out here. But there was no certainty about any of it. He told Mom to have faith, told her no SEAL was dead until there was a body.

And then Morgan arrived and told them all straight-out I was alive, and that was an end to it. He said he’d been in contact with me, had felt my presence. He thought I may have been injured, but I was not dead. “Goddamn it, I know he’s not dead,” he said. “If he was, I’d know.”

By now there were 150 people in the front yard, and the local sheriffs had somehow cordoned off the entire ranch. No one could enter the property without passing through these guardians. There were police cruisers parked along the wide dirt road which leads to the house. Some of the officers were inside the perimeter fences, praying, at short services conducted by two naval chaplains who had arrived from Coronado in the small hours. Just in case, I guess.

Some time before 0500 my mom answered the front door to see SEAL lieutenant Andy Haffele, with his wife, Kristina, standing there. “We wanted to help, any way we could,” said Andy. “We just got here from Hawaii.”

“Hawaii!” said Mom. “That’s halfway around the world.”

“Marcus once saved my life,” said Andy. “I had to be here. I know there’s still hope.”

I can’t explain what all this meant to Mom. She hovered somewhere between hope and total despair. But she’s always said she’ll never forget Andy and the long journey he and Kristina made to be with our family.

It began, I suppose, just as neighborly visits, interspersed with more professional arrivals from SPECWARCOM. But it would turn into a vigil. No one went home, they just stayed, day after day, night after night, all night, praying to God that I was still alive.

When I think about it, these many months later, I’m kind of overwhelmed: that much love, that much caring, that much kindness to my parents. And I think about it, all of it, every day, and I still have no idea how to express my gratitude, except to say I know the door of our home is open to each and every one of them, no matter the hour or the circumstance, for all the days of my life.

Meantime, back up the goddamned mountain, unaware of the mighty gathering still building at home, I was listening to the distant flow of water. Hanging on to the tree, leaning out, wondering how to get down there without killing myself in the process. That’s when the Taliban sniper shot me.

I felt the sting of the bullet ripping into the flesh high up at the back of my left thigh. Christ, that hurt. Really hurt. And the impact of the AK bullet spun me around, knocked me into a complete backflip clean off the fucking mountain. When I hit, I hit hard, but facedown, which I guess didn’t do my busted nose a lot of good and opened up the gash on my forehead.

Then I started rolling, sliding very fast down the steep gradient, unable to get a grip, which may have been just as well. Because these Taliban bastards really opened up on me. There were bullets flying everywhere, pinging and zinging into the ground all around me, ricocheting off the rocks, slamming into the tree trunks. Jesus Christ, this was Murphy’s Ridge all over again.

But it’s a lot harder to hit a moving target than you might think, especially one traveling as quick as I was, out of control, racing between rocks and trees. And they kept missing. Finally I came to a stop in a flatter area, and of course my pursuers had not made the downward journey nearly as fast as I had. I had had a decent start on them, and to my amazement I had come to little harm. I guess I missed all the obstacles, and the earth beneath me was softish and loose packed. Also, I still had my rifle, which to my mind was a bigger miracle than Our Lady of Lourdes.

I began to crawl, going for cover behind a tree and trying to assess the enemy positions. I could see one guy, the nearest of them, just standing and pointing at me, yelling at two others, who were out to the right. Before I could make any kind of a decision, they both opened fire on me again. I did not have much of a shot at them, because they were still maybe a hundred yards up the cliff face and the trees were shielding them.

Trouble was, I could not stand properly, and aiming the rifle was a problem, so I decided to make a break for it, on my hands and knees, and wait for a better spot to take them out. I crawled, not fast but steady, over terrible terrain, full of little hills and dipping gullies. It could hardly have been better country for a fugitive, which I now was, except I could not walk down the gullies, and I sure as hell couldn’t get down those steep slopes on all fours, not having been born a freakin’ snow leopard.

So every time I reached one of those small precipices, I just threw myself straight off and hoped for a reasonable landing. I did a lot of rolling, and it was a long, bumpy, and painful ride. But it beat the hell out of getting shot up the ass again.

I kept it up for about forty-five minutes, crawling, rolling, and falling, staying out in front of my pursuers, gaining ground on the downward falls, losing it again as they ran up on me. And nowhere on that snaking route down the hills did I find a decent spot to get rid of the gunmen who were hunting me down. The bullets kept flying, and I kept moving. But finally I hit some flatter ground and all around me were big rocks. I decided this would be Marcus’s last stand. Or theirs. One way or another. Although I did not know exactly how many of them there were.

I remember thinking, Now, how the hell would Morgan get out of this? What would he do? And it gave me strength, the massive strength of my seven-minutes-older brother. I decided that in this position, he’d wait till he saw the whites of their eyes. No mistakes. So I crawled behind this big rock, checked my magazine, then flipped off the safety catch of my Mark 12. And waited.

I heard them coming but not until they were very, very close. They were not together, which was unnerving, because I could not account for them all. But I could see the spotter now, the guy who was literally tracking me down, not trying to shoot me; he didn’t even carry a rifle. His job was to locate me and then call the others to bring fire down on me. Cheeky little prick.

But it’s the Afghan way. This Sharmak was an excellent delegator. One guy carries the water, another the extra ammunition, and the marksmen don’t have to spend their time searching the terrain. They have a specialist to do this.

This particular specialist was not having much trouble tracking me, probably because I was leaving tracks like a wounded grizzly, scuffing up the ground and bleeding like a stuck pig from both my forehead and my thigh all over the shale.