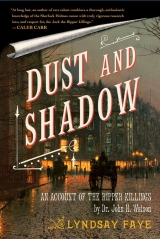

Текст книги "Dust and Shadow"

Автор книги: Lyndsay Faye

Жанры:

Криминальные детективы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

CHAPTER TEN The Destruction of the Clue

I experienced a thin thrill of anticipation on our journey as I realized we were now taking the very path used by the killer in his flight. A walk of ten minutes was reduced to a drive of three, and before we knew it we had pulled up to the aptly titled Goulston Street. The culprit had evidently fled up Stoney Lane, crossed Middlesex Street, and proceeded a block up Wentworth Street before ducking into the more secluded Goulston Street.

When we reached the doorway where Detective Daniel Halse stood guard in the starless darkness like a gargoyle over a turret, we met with a curious sight. There stood a Scotland Yard inspector smiling indomitably, holding a large piece of sponge, and there also stood a quantity of both Metropolitan and City constables, saying nothing but clearly awaiting the arrival of a superior to judge a hostile dispute.

“I still say, Inspector Fry,” declared Detective Halse, as if repeating the crux of his earlier argument for our fresh ears, “that the idea of destroying evidence against this fiend is contrary to every notion of scientific inquiry.”

“And I maintain, Detective Halse,” said Inspector Fry doggedly, “that the civil unrest which allowing this message to remain in view would foment is against the principles of conscience and of British decency. Are you against the principles of British decency, Detective?”

The two appeared as if they were about to come to blows when Inspector Lestrade interposed his lean frame between the antagonists. “For the moment, I shall decide what course we will take in this matter. If you would be so kind as to step aside.”

Lestrade lifted the lantern in his hand and directed its beam at the black bricks. The remarkable riddle, chalked upon the wall in an oddly sloping hand, went in this way:

The Juwes are

the men that

will not

be blamed

for nothing

“You see the trouble, Inspector Lestrade—it is Lestrade, is it not?” inquired Inspector Fry placidly. “Riots on our hands, that’s what we’ll have. I’ll not be the one caught in the middle of them. Besides, there is no evidence the killer wrote these words. More likely the hand of an unbalanced youth.”

“Where is the piece of apron?” Lestrade questioned a constable.

“It has been taken to the Commercial Street police station, sir. The dark smears upon it followed exactly the pattern produced by wiping a soiled knife blade.”

“Then surely he left it deliberately,” I remarked to Lestrade. “As in the past he has left no traces, there is every likelihood he dropped that bloody cloth in order to draw attention to this disquieting epigram.”

“I’m of your mind, Dr. Watson,” Lestrade replied in low tones. “We must prevent them destroying it, if we can.”

“I beg your pardon, sir?” demanded Inspector Fry.

“It must be photographed!” Detective Halse shouted. “And the City Police given an opportunity to examine it.”

“I have my orders from Sir Charles, sir,” said the infuriatingly dignified Inspector Fry.

“Instead, the message might be covered over with a piece of dark cloth,” remarked a constable.

“An excellent notion”—Lestrade nodded—“permitting us to preserve a clue.”

“Respectfully, I do not think that would be in accordance with Sir Charles’s wishes.”

“You could take a sponge to the top line only, with no one the wiser for it,” said Miss Monk.

“What if,” I suggested, “the oddly spelled word ‘Juwes’ only be erased, and the rest remain?”

“By Jove, the very thing!” cried Lestrade. “Better and better—no danger, then, of the sense of it being glimpsed.”

“What if,” replied Inspector Fry in the same maddeningly courteous tone, “we were all to construct daisy chains and drape them so as to shield the words from public view?”

“With all respect, sir,” snarled Detective Halse, “in another hour it will be light enough to photograph. The sun will begin to rise at any moment. We can cover the bloody thing with whatever you like until then, but I beg of you not to throw such a clue as this away.”

“This difficult decision is not mine to make.”

“No indeed, it is mine,” called a forceful, ringing baritone, and there to my astonishment stood Sir Charles Warren himself, the decorated war veteran of the Royal Engineers and the Colonial Office, who had once attempted to relieve a hero of mine, the matchless General Gordon, when he had been hopelessly outnumbered at Khartoum. He was as methodically dressed as if he had not been awoken in the middle of the night with bitter news, and the determined curve of his high, rounded forehead, the authority of his impeccably combed walrus moustache, and the obdurate resolve behind his monocle led me to believe we were in for trouble.

“I have come from Leman Street police station,” he declared, “and I am displeased with the news I have had from that quarter. You are under orders to destroy this monstrous blot of anti-Semitism before the traffic to Petticoat Lane Market is disturbed by it.”

“If you’ll pardon my saying so, sir,” interjected Inspector Lestrade, whose presence I was beginning to welcome with enthusiastic gratitude, “there are, perhaps, less radical possibilities open to us.”

“Less radicalpossibilities? The only radical sentiments being expressed here are written upon that wall and are about to be permanently expunged.”

“This detective, sir, has sent for a photographer—”

“To what purpose?”

“That the message might be made available also to the City force, sir.”

“I do not care two figs for the photographers of the City of London Police. They do not answer to the Home Office over riots, as I undoubtedly will should that absurd phrase remain.”

“Perhaps if we were to cover it, Sir Charles, only for half an hour—”

“I will not be coddled, nor will I be bargained with,” the former military commander averred. “What is your name?”

“Detective Inspector Lestrade, Sir Charles.”

“Well, Inspector Lestrade, you show an admirable passion for police work. You seem to me to have the very best interests of the populace at heart. You will therefore now take this sponge from your colleague and erase that vile scribbling so that we may return to real detective work.”

Inspector Lestrade’s lips set into a forbidding line while Detective Halse, rage twisting his knotted brows, slammed his palm against the wall and stepped aside. Lestrade took the damp sponge from Inspector Fry and approached the writing, stopping to shoot me a significant glance.

“No fear, Doctor,” Miss Monk whispered, “I’ve copied it down during all that racket.”

I nodded to Lestrade, who then proceeded to erase the curious clue. When finished, he shoved the damp sponge against Inspector Fry’s chest and turned to his Commissioner.

“It has been done, as you ordered, Sir Charles.”

“You have averted what could have been a powerful spark to the kindling of social unrest. I’ve business elsewhere. My thanks, gentlemen. As you were.” With that, Sir Charles Warren strode off in the direction of the station and the men began to disperse.

Lestrade regarded the blank wall with pained disquiet. “Dr. Watson, Detective Halse, a word with you please.”

The three of us strolled toward the waiting cab, Miss Monk trailing three or four feet behind.

“I’m not ashamed to say that was a bad business,” began Lestrade, with a dignity I had never before observed in the quick-tempered, rat-like investigator. “Dr. Watson, I expect you to forward copies of that message to both the Metropolitan and the City of London Police.”

“It shall be done immediately.”

“I had never met Sir Charles, you know,” he reflected. “I’m not anxious to repeat the experience—though he is right in that little good it would do us to plunge the entire district into chaos.”

“Surely that is not the point,” I began angrily, but Lestrade held up a hand.

“I’m no spinner of fanciful theories, Dr. Watson, and there are times when, sharp as he is, I think Mr. Holmes would be as well off in Bedlam as in Baker Street. But I am a believer in facts, and that chalked writing was as sound a fact as I’ve ever seen. Good night to you, Detective Halse. You’ll tell your superiors, no doubt, that we were given no choice.”

The City detective, still visibly suppressing his fury, bowed to us and left.

“Lestrade,” I ventured, “I cannot tell you how glad I have been of your presence, but I’m afraid we must leave at once. We have a great deal to report to Holmes, and I fear very much for the condition in which we are likely to find him.”

“Believe me, Dr. Watson, it has been heavy on my mind. I must return to Dutfield’s Yard, but I’ll leave you the cab. This night would have gone a sight differently had Mr. Holmes been here to the end. Next time our police commissioner takes it into his head to expunge a clue, I’d give fifty pounds to have Sherlock Holmes in my corner. I should be grateful if you would tell him so.” Lestrade tipped his hat to us both and strode off into the first brightening light of dawn.

It was then I noted that Miss Monk had grown singularly pale and drawn. I took her arm.

“Miss Monk, are you quite well?”

“It ain’t nothing to speak of, Doctor,” she replied. “Queer stroke of luck that led us to be so in the thick of it, but oh, Dr. Watson—did you ever in all your life even think on a deed so horrible as what he’s done?” She quickly hid her face in her hands.

“No, I have not,” I said quietly. “I feel just as you do, my dear. Get into the cab with me and I shall return you to your lodgings at once. You’ve found better ones, is that not so?”

“If you could drop me at Great Garden Street, Doctor, I’d be grateful. I’ve taken rooms there. Mr. Holmes will want to know everything, and make no mistake we’ll tell him plain what we saw, but not now. I couldn’t rightly bear it now.”

I shook my head as I helped her into the four-wheeler, searching for words of comfort, which rose to my lips and died there in mute sympathy. Miss Monk had been out all night in the cold, pursuing a creature whose great impulse was to brutally slay women exactly like her. She buried her head in the lapel of my greatcoat and we spent the short journey in silence. We soon reached her street, and I saw her to the door.

“You require complete rest for the remainder of the day. Come to Baker Street when you are able. I haven’t words to express my admiration for your courage, Miss Monk, and I know Holmes would say the same.” I left her, returning to the hansom heartsick and defeated as the first true rays of sunlight stole along the cracks of the paving stones.

I had hardly crossed the three shallow steps leading to our front door, nor breathlessly turned my key in the lock, when the door flew open to reveal Mrs. Hudson’s kind, familiar face, spectacles perched upon her head, and oddly done buttons upon her left sleeve.

“Oh, Dr. Watson!” she cried, grasping me by the shoulders. “When I think of what you must have been through! And Mr. Holmes! Seeing him as he was a few hours ago when he arrived here—oh, Dr. Watson, who has done this to him? He wouldn’t speak a word on the subject. I’ve only just finished scrubbing the blood from the kitchen.” The brave woman then dissolved into a brief sob of long-suppressed tears.

“Mrs. Hudson, you shall know all about it,” I returned swiftly, taking her hand. “But first, tell me, is Holmes in any danger?”

“I can’t say, Doctor. I was awoken in the night by a terrible banging. When I saw Mr. Holmes, I thought he had lost his key, but he leaned on the doorframe in such a peculiar way, his arm tied up in black rags, that I knew something was terribly wrong. I let him in at once, but he had hardly walked two steps before he fell against the balustrade and looked up the stairs to your rooms as if they were the side of a mountain. He said, ‘Kitchen, Mrs. Hudson, with your permission,’ and once inside, he fell straight into a chair. ‘Go at once and fetch a doctor,’ he said, in that masterful way of his. ‘Watson cannot be the only one in the neighbourhood. There is that chap at two twenty-seven—mass of dark hair, boots thrice mended, coming in and out and leaving a trail of iodoform—knock him up, if you will be so kind.’ Then he leaned his head back in a kind of faint. I was in such a panic at leaving him that I sent the pageboy instead, and Billy soon enough came back with the fellow. His name is Moore Agar, and he is indeed a doctor. Between them they took Mr. Holmes to his room. Billy has been up and down the stairs four times to fetch the water I heated. But that was hours ago, and Dr. Agar has not come down at all.”

I took the seventeen steps up to our sitting room two at a time and found a tall, handsome, round-featured young man with a determined jaw, a generous shock of wavy brown hair, and deeply set, thoughtful brown eyes checking our mantelpiece clock against his watch. He was dressed as a perfect gentleman in dark tweeds, and I noted an elegantly styled bowler hat thrown carelessly upon the settee, but the elbows and knees of his garments had worn nearly through, and the edges of the hat were beginning to fray. He looked up at my hurried entrance.

“Dr. Moore Agar at your service,” he said earnestly. “I had the honour of stitching up your friend in the next room. He has lost a considerable amount of blood, I am afraid, but I believe he will come out of it all right.”

“Thank God for that.” I exhaled in relief, collapsing into the nearest chair. “That is the very first piece of good news I have had this night. Forgive my exhaustion, Dr. Agar, but I have been taxed in every way possible. Mrs. Hudson tells me we are neighbours.”

“And so we are! I am quartered a mere two doors down. I am just beginning in practice, which is a black mark against me, but you will corroborate my findings, no doubt, and ensure that all will be well with your friend. You are the celebrated Mr. Holmes’s physician, Dr. Watson, no doubt?”

“Merely his biographer. Sherlock Holmes is elaborately uninterested in the state of his own health,” I replied, warmly grasping the hand before me.

Dr. Agar laughed. “It is of no surprise to me,” he replied. “Men of genius are often cavalier about physical trifles. This injury could hardly be termed trifling, however. No fear of muscular impairment, but the tissue damage is quite extensive and the blood loss, as you know, severe.”

“My friend will be very grateful.”

“Mr. Holmes has no reason to be. Perhaps when you have both recovered, you can relate to me more of these extraordinary circumstances, but for now I will leave you in peace. I have injected morphine, but if it is convenient to you, Doctor, I’ll not leave any of my own supplies behind. I imagine you have access to fresh bandaging and so forth; poverty compels me to be rude. Or practicality has trounced my manners. Whichever it may be, I apologize. A better morning to you, Dr. Watson,” the young physician said as he saw himself out and down the stairs.

I made my way quietly into Holmes’s bedroom, where I was peered at malevolently from every angle by the images of infamous criminals carelessly tacked to the walls. My friend, though deathly pale, was breathing regularly and at last, blessedly, unconscious. I swung the door to but did not shut it and returned downstairs for a soothing word with Mrs. Hudson. Then finally, retrieving a quilt from my bed and a generous glass of brandy from the sideboard, I made my home on the sofa within easy call and fell asleep just as the sunlight poured over the windowsills and struggled to flood the room in defiance of the closely drawn curtains.

CHAPTER ELEVEN Mitre Square

When I awoke, I was startled to discover that it was nearly night once more. I sat up groggily and beheld at my feet a tray, laden with a few meats and a cup of cold broth, which did wonders for my state of mind. Supposing my own exhaustion had prompted me to sleep through the day, I at once chastised myself for failing to look in on Holmes. Peering into his chamber, I was comforted by the presence of a candle and another tea tray, partially used, and evidently provided by the conscientious Mrs. Hudson. I made my way upstairs in hopes a wash and change of clothes would restore my energy, but upon my finishing, the dizzy ache in my head revisited me with a vengeance. I tended to Holmes’s bandages and then collapsed once more upon the sofa in hopes that we both would be capable of more upon the morrow.

The birds were still singing, but the quality of light told me it was midmorning when my eyes fluttered open for the second time. For a moment I was harrowed by the disoriented dread one experiences when too much has occurred to be immediately recalled, but a minute’s further repose brought it all back to the forefront of my mind, and I hastened to Holmes’s bedroom.

The sight which greeted me upon my throwing open his door brought a smile of relief to my face. There sat Sherlock Holmes, his hair all awry, telegrams scattered over his lap, the bed literally covered with newsprint, a cigarette held awkwardly in his left hand as he attempted to sift through his considerable correspondence.

“Ah, Watson,” he saluted me. “Don’t bother to knock. Do come in, my dear fellow.”

“My apologies,” I laughed. “I had heard rumour you were an invalid.”

“Nonsense. I am a pillar of strength. I am, in strict point of fact, quite disgusted with myself,” he added more quietly—with a tweak of one eyebrow that told me more than his words of his profound dissatisfaction, “but no matter. Up until this moment, Mrs. Hudson and Billy brought me everything I required. Now you must sit in that armchair, my boy, and tell me the whole ghastly mess.”

I did so, omitting nothing from our universal dismay at his misfortune, to the state of the second girl’s ears and the dispute between our good Lestrade and his own Commissioner. A solid hour must have passed, Holmes’s eyes closed in concentration and my mind straining for each and every detail, when I arrived at Dr. Moore Agar and my own homecoming.

“It is unforgivable that we have lost Sunday! The police no doubt have swept both crime scenes of any useful evidence in my absence, and this business of the chalked message is altogether tragic. I cannot remember anything at all,” Holmes confessed bitterly, “from the time I alighted the hansom until this morning at around nine o’clock. Of course I deduced the profession of two twenty-seven Baker Street months ago, but the business of the summons Mrs. Hudson related to me is merely a painful blur.”

“I was at a continual loss whether to come after you or remain in the East-end.”

“Your sentiments do you credit, as ever, Doctor, but were you not present, how would you explain to me the seven urgent messages I have received so far this morning?”

“Seven! I am all attention.”

“Let me relate them to you in the order I read them. First, a note from the doughty Inspector Lestrade, with well-wishes, requesting a facsimile of the curious inscription you fought fruitlessly to preserve.”

“Miss Monk has given it to me. I shall send copies immediately.”

“Next, President George Lusk of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, with compliments, informs me he has written the Queen demanding a reward be offered.”

“Good heavens! London will be a madhouse.”

“My sentiments echo your own. Here we have a very considerate note from Major Henry Smith, who has enclosed the results from the postmortem of the City victim. We shall return to that in a moment. If you would be so kind as to pour me another cup of coffee, my dear fellow, as my usual motility has been greatly hampered by our neighbour two doors down. Much obliged. Fourth, a telegram from brother Mycroft: ‘Will visit at earliest possible convenience—great uproar in Whitehall. Mend quickly; your death would be most inconvenient at this time.’”

“I heartily agree.”

“Fifth, Miss Monk asks that we wire her a convenient time to meet.”

“She has proven herself to be a woman of extraordinary fortitude.”

“For which I am exceedingly grateful. Item the sixth, calling card of Mr. Rowland K. Vandervent, who likewise begs an audience. Finally, there is a preposterous missive from a reporter who claims to know more than he should demanding an interview in the interests of public awareness.”

“Hardly worthy of your immediate attention.”

“I am inclined to be as dismissive, although there is an ominous tone to his wording. See for yourself.”

The paper was typewritten on a single sheet of cheap off-white paper, with some dark smudges near the margins.

Mr. Sherlock Holmes,

In the interests of the public and of your own reputation, I strongly suggest you meet me at Simpson’s in order to address some serious questions. I shall await you at ten o’clock this evening, alone.

Mr. Leslie Tavistock

I turned the inexplicable summons over in my hands. “Holmes, the author mentions nothing of being a pressman.”

“He needn’t, for it is all too obvious to any specialist in typewriters. Observe the characteristics of this particular machine. Mr. Tavistock ought to be deeply ashamed, if for nothing else, of the nearly nonexistent tail of the ys, the ramshackle upstroke of the ds, and fully nine other points indicating nearly continuous wear.”

“Surely other professions than journalism are hard on typewriters?”

“None that brings one’s fingertips into such intimate congress with cheap newsprint ink. There are several other points I might make, but I fear we must return to the bloody business of Saturday night and leave our mysterious reporter to his own devices. Here is the autopsy report writ brief by Major Smith. Read it aloud, would you, Watson, so that I may be sure of my facts.”

“‘Upon arrival at Golden Lane, a piece of the deceased’s ear fell from her clothing. There were three incisions in the liver of varying size, a stab to the groin, and deep cuts on the womb, colon, lining membrane above the uterus, the pancreas, and the left renal artery. I regret to say that the left kidney was taken entirely out of the body and retained by the killer.’ But this is despicable, Holmes!” I exclaimed in disgust. “He has taken another grisly memento.”

“I had anticipated as much.”

“But Holmes, the kidney is lodged behind several other significant organs, not to mention shielded by a membrane. He must not have feared interruption to have absconded with the kidney of all objects.”

“Hum! That is indeed remarkable. Pray continue.”

“‘The lack of clotting from the abdominal region indicates that she was entirely dead when these acts occurred. Enclosed is a complete list of the deceased’s belongings and attire at the time of her death.’ It is signed with respects from Major Henry Smith, and with regrets that you could not yourself have been in attendance.”

“I can assure the major his regrets are entirely dwarfed by my own.” Holmes sighed. “I’ve made an unspeakable hash of it, I don’t mind telling you.”

“Are we really no further along?”

“Well, I would hardly say that. We know that this ‘Jack the Ripper’ letter may well be the work of the killer, for a detail like notched ears is very unlikely to turn up in both jest and in fact. We know that he has an iron nerve to locate and remove a kidney. We know that one effective method of carrying off organs is to cart about an empty parcel, for I have no doubt but that the package I observed under his arm was later used to transport a very sinister object indeed. And I have my reasons for suspecting that this ‘Jack the Ripper’ has taken a very strong dislike to your humble servant.”

“What on earth do you mean?”

“Watson, do you recall the letter I received in March of last year just after we returned from Colwall?”

“After the affair of the Ramsden heirloom? I seem to remember something of the kind.”

“I have been looking over the handwriting. Though disguised, I am certain that it was the work of the same man; the hooked end-strokes are indicative, but the pressure on his descending lines concludes the matter. Which means he wrote to me—”

“Before a single murder had been committed!”

“Precisely.” Holmes looked pensively at me for a moment. “If you would go so far against your conscience as to prepare a dose of morphine, Doctor, I shouldn’t refuse it. I’ll do it myself if you prefer, but…”

I located his bottle on the mantel amongst a litter of pipe cleaners and reflected, as I was readying my friend’s pristine little syringe, upon the oddity of the situation. When I turned back to Holmes, I saw with dismay that he was attempting to extricate himself from the bedclothes with no very great degree of success.

“Holmes, what the devil do you think you are doing?”

“Readying myself to go out,” he replied, using the nearest post of the bed to steady himself as he rose.

“Holmes, have you completely taken leave of your senses? You cannot possibly expect—”

“That any evidence will remain to be found?” he lashed out in vexation. “That is one damnable fact, Watson, of which I am all too well aware.”

“Your condition is—”

“Of the utmost irrelevance! In any event, I do myself the honour of assuming I shall be accompanied by a skilled physician.”

“If you imagine that I have any intention of allowing you to leave these rooms, you are delirious as well as badly injured.”

“Watson,” he said in another voice entirely. To my immense surprise, it was not a tone I had ever heard from him before. It was far quieter than his usual measured voice, and far more grieved. “I have maneuvered myself into an intolerable position. Five women are dead. Five. Your intentions are commendable, but take a moment to imagine what it would be like for me to receive news of the sixth.”

I stared at him, weighing considerations both medical and personal. “Give me your arm,” I said at length. The sight of innumerable tiny scars scattered like miniature constellations pained me as it always did, but I made a sincere effort not to show it as I administered the injection.

“Thank you,” said he, starting haltingly for his wardrobe. “I will see you downstairs. I advise you to wear your old army coat if you do not wish to look hopelessly out of place.”

Hesitantly, I donned an old astrakhan and the heavy coat I had needed so seldom in actual service, and dashed down the stairs to procure a four-wheeler. If Holmes was determined to visit the crime scene, best it be done immediately, for the sake of his health more than of any evidence remaining.

Cabs were plentiful, and Holmes himself was seated on the front steps of 221 when I returned. He wore the loose-fitting attire of a disengaged naval officer, complete with seafaring cap, heavy trousers, a rough work shirt, cravat, and a pea jacket through which he had managed to pass his left arm, the other side draped over his sling.

“You wish to remain anonymous?” I remarked as I helped him into the hansom.

“If there are any neighbours willing to communicate useful gossip, they’ll do so far more readily to two half-pay patriots.” He added ruefully, “In any event, the garb of the British gentleman is well-nigh impossible to achieve with one arm.”

On our route to the East-end, as Holmes appeared to doze and I gazed out the window in uneasy contemplation, I saw that London had changed since I had last set foot out of doors; a veritable snowstorm of papers printed in bold block capitals was pasted to every ready surface. I soon discerned the leaflets were all identical appeals from the Yard to the citizenry, urging the public to come forward with any helpful information.

We had turned north on Duke Street and approached one of the entrances to Mitre Square when the cabbie stopped abruptly and began to grumble sotto voce about “thrill seekers” who evinced “all the human decency of vultures.” When he saw the denomination of coin I offered him, he grew more acquiescent, however, and agreed to wait until we had finished in the square.

Sherlock Holmes leaned heavily on his stick as we traversed the long passage, but he scanned the floor and walls of the alley as a hawk seeks prey from on high. Mitre Square, far from being the sordid cul-de-sac my memory had painted it, was an open space, well kept by the City but surrounded by featureless buildings, few of which proved to be tenanted. Those warehouses which were occupied were also guarded, for a small knot of men chatted earnestly where we had viewed the body two nights previous.

“I take it the poor woman was found in that southwest corner?” queried Holmes.

“Yes, the City constable discovered her there. I don’t like to think of the condition she was in.”

“Very well. I shall search the rest of the square and surrounding passageways first, for it doesn’t seem likely we can peruse that area without inciting unwelcome conversation.”

I followed the detective as he made an exhaustive study, exiting the square by means of the constrictive Church Passage, which led to Mitre Street, and returning through the one corridor left to be explored, which passed by St. James Place and the Orange Market. Though Holmes had been at work for only perhaps half an hour, the strain of simply remaining upright had already begun to take a visible toll upon his haggard countenance.

“As far as I can make out by memory,” said he, “the path I followed after leaving you at Berner Street took me north via Greenfield Street, Fieldgate Street, then Great Garden Street and thus to the small maze surrounding Chicksand Street, which is where I encountered our quarry. I then made my way back to Berner Street, whilst he, inexplicably, proceeded here to a largely emptied commercial district. I imagine he traveled down Old Montague Street, which becomes Wentworth Street, then narrows again into Stoney Lane, which finally led him straight to where we stand. Then, and here we are blessed, for the extraordinary is always of use to the investigator, he did something positively absurd. He killed a woman, then disemboweled her in an open square with three separate entrances and any number of guards within—but we have visitors, Watson. It was only a matter of time. Let me do the talking, if you don’t mind.”

A middle-aged man with greying muttonchop whiskers, a shabby bowler hat, and the physique of a dray horse approached us, a tentative smile fighting for supremacy with his suspicious and hooded eyes.