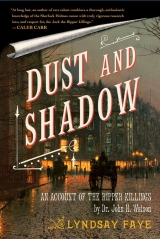

Текст книги "Dust and Shadow"

Автор книги: Lyndsay Faye

Жанры:

Криминальные детективы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO The Disappearance of Sherlock Holmes

I saw nothing of my friend the next day until nearly eight o’clock, when an exceedingly disheveled character wearing the filthy oilskins and the high boots of the men who risk their lives raking the sewers for coins saluted me and disappeared into Holmes’s bedroom. In half an hour he emerged again in grey tweeds, collected his pipe, and sat down at the table with the look of a man who relishes the work ahead of him.

“And what has that scavenger been doing today?”

“He has set foot in realms where Sherlock Holmes, temporarily at least, dares not tread. What is for supper?”

“Mrs. Hudson spoke of lamb.”

“Admirable woman. Just ring the bell, my dear fellow. I haven’t thought of food since early this morning, for there was a great deal of work to be done.”

“You have been in the East-end?”

“Well, for part of the day. I had other errands. I’ve stopped by the Yard, for instance.”

“In that getup?” I laughed.

“I demanded to see Inspector Lestrade. I revealed I had pressing information to relate, which would profit him immensely. His colleagues hesitated. Then I was forced to admonish them that if I went with my information to the papers instead, they would look rather foolish. This suggestion altered their mood, and I was in Lestrade’s office a moment later. I revealed my identity, much to the good inspector’s irritation, and I asked him some key questions.”

“Such as?”

“In the first place, the force are very put out by this Tavistock mongrel’s theorizing but are also anxious to avoid accusations of favouritism. Some of the more active fellows have suggested arresting me in the interests of thoroughness and public opinion.”

“On what evidence, in God’s name?”

“Incredibly, there really was a bloody knife found discarded a few streets away from Catherine Eddowes, but Lestrade never bothered to mention it to us because it was so unlike the double-sided blade which the Ripper used. Its discovery was a complete coincidence, but the villainous mind of either Leslie Tavistock or his foul source hit upon the happy notion that Eddowes could have wielded it in defense. In such a state of panic, it counts for nothing that any British jury would dismiss the whole tale in the blink of an eye. I can’t even bring charges of libel, for he hasn’t penned an untrue word.”

“Surely he has gone too far!” I protested.

“Watson, if the newspapers could be punished for speculation, every publication in England would soon enough be bankrupted. After I quit the Yard, I made my way to Whitechapel and looked in on Stephen Dunlevy. He proclaims his innocence in the strongest terms.”

“No doubt that is to be expected,” I said tightly, while privately thinking that if Dunlevy continued to operate under false pretenses with us, all the while endeavouring to enter the good graces of Miss Monk, I would have scant choice but to throw him in the Thames.

“I am inclined to believe him,” Holmes mused. “Indeed, I feel ever more certain that there is a malevolent force at work determined to impede my progress. Perhaps my mind detects conspiracy where none exists, but these small persecutions play directly into the Ripper’s hands by tying mine.”

“I should hardly call them small persecutions.”

My friend waved his pipe dismissively. “I’ve nothing further to report on the subject, for we can hardly know more until we have seen Tavistock.”

“We intend to see Tavistock?”

“We are to meet him at Simpson’s for cigars at ten.”

“You will then be able to claim acquaintance with the lowest form of life in London other than Jack the Ripper,” I stated dourly.

Holmes laughed. “Well, well, we go into it with the comfort of a good day’s labour behind us.”

“But what else have you been doing, Holmes? You left early this morning.”

“My time has not been wasted, I assure you. Ah! Here is Mrs. Hudson, and I beg your permission to confine my attentions to the tray she carries with her.”

That night, as many others had been that October, was shrouded in pungent fog, and we wrapped our mufflers tight about our faces and ducked our heads as if we walked against a strong wind. Despite the company which awaited us there, I was heartily glad to finally discern, nearly five yards in front of us, the façade of Simpson’s glimmer through the murk of the atmosphere.

The polished mahogany and gentle clink of crystal and silver improved my spirits, at least until we found ourselves in a private salon with a fire in the grate and stately palms in the corners, for it was then I laid eyes once more on Leslie Tavistock. In his office I had hardly taken notice of his physique, but now I saw he stood rather below average in height, with sharp, alert brown eyes which bespoke cunning rather than intellect. His light brown, slicked-back hair and expressive hands enhanced the impression of a man who had ascended to his current position by whatever means he had thought necessary.

“It is an honour to meet you in person, Mr. Holmes,” he cried, approaching my friend with a hand outstretched, which my friend studiously ignored. “Ah, well,” he continued, turning the failed greeting into a flourish of understanding with a flick of the wrist, “I can hardly blame you. Public figures grow so accustomed to hearing their praises sung by the adoring masses that any censure can be most disconcerting.”

“Particularly when said masses take it into their heads to kill you,” Holmes replied dryly.

“By Jove!” Tavistock exclaimed. “You didn’t venture into the East-end again, did you? It isn’t a safe neighbourhood, you know. But how you interest me, Mr. Holmes. Would you care to elaborate on what you were doing there?”

My friend smiled the slow, frigid smile of a bird of prey. “Mr. Tavistock, beyond the facts that you are a bachelor, a snuff user, a union advocate, and a gambler, I know nothing whatever about you. However, I do know that if you refuse to reveal to me your source for these damning articles, you will very soon come to regret it.”

While I was familiar enough with Holmes’s methods to note the disheveled attire, the fine dust on his shirt cuff, the discreet pin, and the two open racing periodicals upon the table, the journalist was not. A twinge of fear crossed Tavistock’s features, though he attempted to hide his chagrin with a laugh while he poured three glasses of brandy.

“So you can make clever guesses about people. I thought that an invention of Dr. Watson’s admirable style.”

“The guesses, as you term them, are in fact the very least stylistic aspect of the good doctor’s literary efforts.”

Tavistock handed us two snifters of brandy, which we accepted, though I have never been less inclined to share a drink with anyone in my life. “Mr. Holmes, you seem to have got it into your head that I have done something terribly wrong. I assure you, though my humble pieces may have afforded you some temporary inconvenience—which, believe me, I heartily regret—my responsibility is to inform the public.”

“Do you really wish to act in the public interest?” Holmes asked.

“Without question, Mr. Holmes.”

“Then tell me who approached you.”

“You must understand that is impossible,” the insufferable man replied smugly, “for his interests are also those of defending the populace, even if it means defending them from you.”

“If you dare to imply to our faces again that my friend is capable of such barbarities, you will answer for it to me,” I could not help but interject in fury.

“We are going,” Holmes said quietly, setting his glass down untouched.

“Wait!” Tavistock called out, anxiety clouding his clever features. “Mr. Holmes, I am a fair man. If you were to grant me an interview, I assure you our next publication would present you in a very different light indeed.”

“Mr. Tavistock, it should not shock you to hear that you are the very last person in London to whom I would entrust any words on that subject,” my friend replied icily.

“Forgive me, Mr. Holmes, but that is absurd. You have the opportunity to emerge from the mud a figure of the purest intentions.”

“You are dreaming.”

“It is the most compelling story in decades!” he cried. “Sherlock Holmes, noble sentinel of justice or perverse scourge of carnality? All you have to do is provide me with a few salient details.”

“If you will not reveal your source, you are not of the slightest use to me.”

Tavistock’s eyes narrowed slyly. “Do you really think your investigation stands any chance of success if the residents of Whitechapel consider you the killer?”

Holmes shrugged, but I could see from the tightening of his jaw that the same thought had crossed his mind.

“Come, now.” The reporter pulled a notebook out of his coat pocket. “Just a few statements, and we’ll make the most stirring headline you’ve ever set eyes on.”

“Good night, Mr. Tavistock.”

“But your career!” Tavistock protested desperately. “Can’t you see, it doesn’t matter to me, so long as the story is mine!”

Holmes shook his head, disgust at the pressman’s admission clouding his brow. “I think the air is cleaner out of doors, Watson.”

Outside, the acrid atmosphere remained viscous and faintly sickening. Cabs could not operate in such weather, so we walked toward Regent Street in silence, each lost in uneasy reflections. I could not help but agree with Tavistock’s taunting declaration: if feelings against Holmes continued to run as high as they had the night before, not merely his investigation but his very life was in danger.

We had nearly reached Baker Street when Holmes broke the silence. “You are entirely correct, my dear fellow. I cannot hope to act with impunity in Whitechapel while Tavistock’s slanders still retain their power. In the last five minutes, you have glanced at my profile four times; you are right in observing that the London Chronicle’s illustration was disturbingly accurate, and we both suffered the results last night.”

I smiled in spite of myself, and Holmes sighed ruefully. “It’s a lucky thing I have only one confidant. Explaining myself only knocks little holes in the masonry of my reputation.”

“Your reputation—”

“Has greater problems just now, to be sure. I am glad I have laid eyes on Tavistock, in any event. I was willing to take your word he was a scoundrel, but there is nothing like exposure to the genuine article. He let one curious phrase drop.”

“Did he?”

“He said his source wished to protect the populace. If he thinks the populace will be any better off without me, he is either a lunatic himself or a—” I waited hopefully, but soon Holmes shook his head and continued. “We can discard one hypothesis—that this Tavistock cur has some reason to persecute me. He made it nauseatingly clear I could be inducted as prime minister or be drawn and quartered with my head on a pike just so long as he is allowed to write it up.”

“Is there anything I can do, Holmes?”

We had reached our own door, though it was barely discernible through the gloom. “No, no, my dear fellow. I fear that it is I who must act. And act I shall.”

That night Holmes folded himself into his armchair with one knee drawn up to his chin, staring fixedly at the numbers on the torn page from the Ripper’s gift of a cigarette case. For more than an hour he remained in the same position with his eyes nearly closed, as still and solitary as an oracle, smoking endless bowls of shag, until I retired to bed and my own ruminations about the trials before us.

The next morning I found a note in my friend’s clear, fastidious script wedged under the butter dish.

My dear Watson,

It is just possible that my investigations will not allow me to return to Baker Street for some brief while. You will appreciate that time is of the essence, and my inquiries in the East-end are of such a nature they can be conducted far more effectively alone. Do not worry, I beg, and do not stray too far afield, however sordid London has grown, for I hope very soon to have need of your assistance. Letters will reach me if directed to the Whitechapel Post Office branch, to be left until called for by Jack Escott.

S. H.

P.S.—As my new researches have taken a more dangerous turn, you will be delighted to learn I have directed Miss Monk to take a paid hiatus.

I need hardly state that the postscript rather worked against Holmes’s prior instruction not to fear for his own safety. While acknowledging to myself that he could indeed work more efficiently alone, and had done so during many of our shared cases, unbidden thoughts also flew into my mind of occasions when the danger had proven too great for one man, even if that one man was Sherlock Holmes.

Mrs. Hudson poked her head round the edge of the door. “It’s Miss Monk to see you, Dr. Watson.”

Our colleague’s expressive features were weighted with concern. She pulled off a new pair of gloves and concealed them in a pocket.

“Good afternoon, Miss Monk.”

“Mrs. Hudson’s just offered tea, though it ain’t my usual time. She is a dear one, isn’t she?”

“Please sit down. I am delighted to see you, considering—”

“Considering I’ve been sacked?” she asked with the trace of a smile.

“Good heavens, no!”

I handed the note to her, and her eyes flew back to mine in alarm. “What’s he up to all alone, then?”

“I am afraid that Sherlock Holmes is the most solitary man I have ever encountered in my travels on three separate continents. I have no more idea what he is doing than you do.”

Biting her lip, she approached the fire I’d allowed to die down and stabbed it combatively with the fire iron. “I’ve had a telegram from him this morning before breakfast. I ain’t getting paid for sitting in pubs chatting up drunken judies,” she declared, straightening. “What can we do?”

“Your sitting in pubs certainly led us to some intriguing results last time.”

“It’s a gift, I’ll own. But the well’s run a mite dry. Thought I’d hit a good line t’other day, but her idea the Knife can transport himself by electricity sort of threw a wet blanket on the rest of her story. Poor Miss Lacey. It’s the laudanum, I promise you. What else?”

“Miss Monk, as much as may be dark to us, I’ve learned that most of it is generally clear to Holmes,” I pointed out. “It may be foolish to take any precipitate steps.”

“I’ll be damned if there isn’t somethingwe could do, even if it’s to patrol the streets with little striped wristbands.”

“Well,” I replied slowly, “it would certainly profit Holmes to have Leslie Tavistock discredited.”

“The journalist? I’d give a good deal to see his face in the mud.” My companion shot up again and took a turn around the carpet, her freckled brow tense with concentration.

“Miss Monk?”

“It may not wash. But if it worked…”

“My dear Miss Monk, what is it?”

“Doctor, it would do Mr. Holmes a world of good if we could discover where Tavistock digs up his trash, wouldn’t it?”

“I should think so indeed.”

“I know I can do it.”

“What precisely do you have in mind?”

“I don’t rightly like to tell you, as it may come to naught. But if it works, it might be a ream flash pull. It’ll take a bit of conniving on my part, perhaps, but if he can get it…” She came to a breathless halt. “Tell you what, I’ll bring it here to you and you can decide.” She retrieved her black gloves and waved them at me from the door.

“My dear Miss Monk, I absolutely forbid you to take any risks in this matter!” I called out.

It was to no avail. A moment later she was halfway down the stairs. I could just hear her good-natured apologies to Mrs. Hudson over the tea things as she lilted out the front door into the fog like a melody on the breeze.

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE The Fleet Street Enterprise

As it happened, I did not see Miss Monk again until Tuesday, the thirtieth of October, during which heart-wrenching period I heard not a single word from Sherlock Holmes. According to Lestrade, the men of the Yard were greatly discouraged. Rumours of mad kosher slaughtermen and deranged doctors ran so wild in the district that it was all they could do to keep the peace. And as if it were not enough that they suffered defamation from every quarter for their failure to locate the Ripper, they now faced the burden of diverting a significant portion of their force to police the Lord Mayor’s resplendent annual procession on Friday, the ninth of November.

It may be imagined that, with the weight of the Whitechapel problem bearing down upon me, not to mention the disturbing absence of Holmes, I spent my days endeavouring to relieve my tumultuous state of mind without straying too far from Baker Street should matters come to a head. Novels were intolerable, and the atmosphere of my club stale and wearisome. On that sleepless Tuesday night, while attempting to defy all my friend’s injunctions against recording a case I had filed under “The Adventure of the Third Candle,” I had just determined that a glass of claret would do me more good than harm when I heard the avid ringing of the downstairs bell.

Knowing Mrs. Hudson to be long abed, I hurried down the stairs, fully dressed, for I had not yet entertained any thought of sleep. When I unlatched the door, I discovered, to my great surprise, Miss Monk and Stephen Dunlevy.

“Forgive the lateness of the hour, Dr. Watson,” Dunlevy began, “but Miss Monk was determined not to let the matter wait.”

“You are most welcome. I have been expecting Miss Monk, in any event.”

Once upstairs, I opened the claret and located two more glasses. Dunlevy sat in the basket chair, while Miss Monk stood proudly before the fire with the air of an orator who has been asked to make a statement. When I had seated myself, she set her glass upon the mantel and drew a small object out of her garments.

“It’s a present for you, Doctor.” She grinned broadly as she tossed a piece of metal through the air and I caught it, turning it over in my hand.

It was a key. “All right,” I said, laughing, “I’m game. What does it open?”

“Leslie Tavistock’s office.”

“My dear Miss Monk!”

“I’d a mind to see whether Dunlevy here was good for anything apart from shadowing decent folk,” she said happily, settling herself upon the arm of the sofa. “But I know you was worried about taking any steps wi’out Mr. Holmes, for good reason too, so once we’d got it, we legged it straight here to turn it over.”

“Mr. Dunlevy, would you care to elaborate how this came into your possession?”

The young man cleared his throat. “Well, Miss Monk did me the honour of appearing at my door the Thursday before last, and explained to me her belief that, as I am a journalist and journalists are a clubbish sort of folk, always rubbing shoulders to be apprised of the latest developments, it was inconceivable to her that I would not have an acquaintance at the London Chronicle.Miss Monk’s conjecture was not entirely correct, but it may as well have been, for I’ve a friend at the Starwho has a very close connection with a chap by the name of Harding, who is employed there.”

“I see. And then?”

“The young lady’s idea, and a very clever one if I may say so, was to coerce Harding into taking an impression of Tavistock’s key. As it happens, no coercion proved necessary.”

“Tavistock’s a complete rotter,” Miss Monk interrupted. “We might have known as much, the way he went after Mr. Holmes.”

Dunlevy quickly suppressed what appeared to be the beginnings of a fond smile and went on. “As Miss Monk says, there is no one so universally reviled at the London Chronicleas Leslie Tavistock. It took a couple of days’ management, but I met with Harding in the company of our mutual friend for a glass of beer, made the suggestion, and was instantly heaped with praise for my idea of playing a prank on the most friendless man in journalism.”

“A prank,” I repeated, beginning to see the inspired simplicity of their plan. “What sort of prank do you intend?”

“Oh, I daresay we could accomplish something nice with paint, and there’s always dead rats to consider,” Miss Monk remarked with an air of delighted nonchalance. “There’s a horse slaughterer not far from Dunlevy’s East-end digs. And of course, once we were in the office—”

“This little pleasantry may take us considerably more time than one would think,” I finished.

“With all his papers just lying about, it would be a shame not to glance through them, eh, Doctor?”

“Wait a moment. We know nothing of Tavistock’s hours, or indeed, those of the building itself.”

“Harding has proffered very eager cooperation,” Dunlevy explained. “It seems he was once investigating a story which Tavistock got wind of, and had it stolen right out from under him. He took an impression of Tavistock’s office key, and this duplicate was in my hands a day later. There is no getting into the building undetected during the week, for as you must know the press keeps all hours. Saturday night is the only clear time, for as they have no Sunday publication, Harding says that the lot of them scatter to pubs in the area or go home to their families.”

“What of security when the building is locked?”

“Harding is prepared to lend us his own outer door key in light of the nobility of our mission. As for security, the offices have not seen fit to employ a night guard. There will no doubt be a beat officer of some kind nearby, but that is easily ascertained.”

“It will put us in a monstrous position to rifle through his office in such a manner,” I cautioned.

“That may be, but the cause is righteous and the quarrel just. Mr. Holmes has a right to know who has invented these aspersions, and though he seemed to accept my protestations of innocence, I would be very glad to see it proven.”

“It is alarming to consider what steps Tavistock could take if we are caught.”

“I know, Doctor,” said Miss Monk sympathetically, “but if you’ll just reread those two articles what weren’t fit for dead fish to be wrapped in, it’ll shore up your nerve right quick.”

I may say without undue pride or fear of contradiction that I have never been a man to back away from danger where a comrade’s interests are concerned. “Saturday,” I mused. “It gives us three clear days to perfect our plans.”

“And who knows but that Mr. Holmes may be back by then!” Miss Monk exclaimed. “But if we’ve still seen no sign of him, we can at least try to clear up one dark spot in this bloody mess.”

“Miss Monk, Mr. Dunlevy,” said I, rising from my chair, “I congratulate you. Here’s to the health of Mr. Sherlock Holmes.”

In such a depth of numbing uncertainty, it was impossible not to feel uplifted at the mere idea of a mission. Still later that night, when I at last blew out my bedside candle, I began to wonder if—for a mind as incandescent as that of my friend—perhaps inaction could truly be so torturous that a syringe and a bottle of seven-percent solution seemed the only tolerable recourse.

Our schemes developed quickly. Miss Monk was kind enough to hawk some handkerchiefs in the vicinity of the building until she was warned off by a policeman, after which she quietly pursued him and found that his route took him directly past the entrance: a cause for anxiety, perhaps, for a callow housebreaker, but hardly of any concern for one possessed of a set of keys. Moreover, the enthusiastic Harding informed us that Tavistock’s office did not look out upon the street, so that a lamp could be lit there and never be noticed in the darkness of the surrounding building.

There was initially some discussion regarding who would attempt the endeavour itself, but Miss Monk would not hear of being left behind, and as Dunlevy’s presence was deemed likewise necessary, I faced breaking into Leslie Tavistock’s place of employment as part of a courageous band of three. We met on Friday to work out a story in case of emergency, the following evening at eleven fixed as the start of our nocturnal enterprise.

At a quarter after ten that Saturday night, I walked as far south as Oxford Street, then hailed a cab, for the air had cleared considerably and the last traces of fog swirled about the windows as playfully as a child’s toy ribbon, tempting faceless passersby further into the night. We approached the Strand by way of Haymarket, and I alighted from the hansom with ten minutes to spare. Turning onto a side street, I descended the steps of a tiny public house and hailed Miss Monk and Mr. Dunlevy, who had engaged a small corner table lit by an oil lamp which I do not think had ever been cleaned.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” declared Stephen Dunlevy, a smile tugging at the corner of his moustache as we raised our glasses, “I give you Mr. Alistair Harding, a man who holds a grudge with vigour and enthusiasm.”

“Miss Monk, have you the bag?” I inquired.

She tapped a small burlap sack with the toe of her boot.

“In that case, let us be on our way. Miss Monk, we will see you in ten minutes.”

Leaving Miss Monk in the pool of light at the table, Dunlevy and I strolled past the last stately buildings of the Strand, through the demarcation of the Temple Bar where the great stone archway had once stood, and thus entered Fleet Street, that strident nucleus of British journalism. The area was calm so late on a Saturday, and the general impetus of the pedestrians seemed that of departure rather than arrival.

Dunlevy approached the front door of 174 Fleet Street, stolid block lettering declaring it to be the home of the London Chronicle,and inserted Mr. Harding’s key in the lock. Seconds later, we were within the vestibule, Dunlevy pulling a dark lantern from within his voluminous coat.

“I see no sign of occupation,” he mouthed cautiously.

“We will know for certain once we have reached the upper floor.”

With painstakingly silent tread, we advanced up the stairs to the first floor, where no more light met our eyes than the beam of our own lantern. I knew my way, and passing through the common room, we proceeded directly to the second office, secured with one simple lock. I withdrew the key from my pocket and opened the door.

Dunlevy fully unshuttered the eye of the dark lantern and the room flooded instantly with light. Papers lay strewn across the desk, and files sat upon bookcases and lay open over reference volumes. We began shuffling through the scattered texts, careful to keep them in order lest the true reason for our nocturnal visit be revealed. We had been reading every scrap of paper we could lay our hands on for several minutes when a low whistle from Dunlevy arrested my attention.

“Hullo! Here is something.”

I abandoned the disjointed jottings of my own chosen page and focused instead upon Dunlevy’s, which read:

There have been no murders since Holmes was wounded, which is very likely not a coincidence.

Has expressed contempt for police in past cases.

Continues to frequent the East-end.

Then, scrawled at the bottom of the page:

Holmes has disappeared. An admission of guilt?

“Good lord, Dr. Watson, I never anticipated there may be more of this garbage in the works.”

“I confess I feared as much, but this is uglier than the others combined.”

“But see—this page could not have been written by Tavistock. The handwriting is different.” From down the stairs, I heard the creak of the outer door.

“What sort of papers are those?” I asked.

“This is the beginnings of an article, and here is a letter, signed by Tavistock, not yet sent. These are in the same hand as most of the documents on the desk. The note about Mr. Holmes must be suggestions from the rascal’s source.”

Miss Monk entered and shut the door behind her. “What’s up, then?”

“This note seems to have been penned by the cause of all this trouble,” said I.

She looked over my shoulder. “A man’s writing. Mr. Holmes would make something of it.”

“I would take it to him, but there cannot appear to be anything missing,” I considered, copying the noisome text into my pocketbook.

“Is there an envelope?” Miss Monk asked. We cast about for one in the basket full of crumpled scribblings. Soon she emerged from under the desk with a flush of triumph.

“Dated Saturday the twentieth. Paper matches the envelope, addressed to Leslie Tavistock, London Chronicle.It’s in the same hand! We can take the envelope, for it won’t be missed.”

Our search brought to light more documents but no new information. The same man had written three other letters to Tavistock, once to arrange an appointment and twice to forward fresh news of Holmes, but as they had already resulted in calamity, they told us nothing. At length, as the hour approached one o’clock in the morning, I suggested we depart.

As Dunlevy and I cast a final glance over the room to ensure we had not left any identifying traces, Miss Monk picked up the burlap sack she had propped against the wall, and, with an air of courtly ceremony, deposited its contents upon the desk, dropping the bag in the dustbin with a final toss of her head.

We made our way downstairs. As I reached my hand toward the door handle and the outside world beyond it, I started at the sound of approaching footsteps. I signaled my companions to step back. Scarcely breathing, I prayed silently to hear the same tread depart, but to my dismay, the handle of the door was tested and then pushed carefully open.

In an instant, Stephen Dunlevy opened the shutter of the dark lantern and sprang before the door, his hand raised as if to open it when a grey-whiskered police constable entered with his truncheon in hand.

“Oh, I say! How you startled me, Officer,” Dunlevy exclaimed.

The stout fellow returned his truncheon to his belt but regarded us with suspicion.

“Do you mind telling me what the three of you are doing here? There’s never a soul in the building at this time on a Saturday.”

“To be sure, my good man. I admit, though, you gave us a fright.”

“No doubt,” he replied tersely. “You have a set of keys, do you?”

“Indeed, yes. I must say, sir, I admire your thoroughness in policing, if you always check locked doors while on your beat.”

“I string the locked doors, as most of us do. The string was broken.”

“Aha! Very workmanlike, Constable…?”

“Brierley.”

“Well, then, Constable Brierley, my colleague and I required absolute secrecy in order to interview this young woman.”

“And why might that be?”