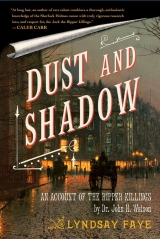

Текст книги "Dust and Shadow"

Автор книги: Lyndsay Faye

Жанры:

Криминальные детективы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

“Stephen Dunlevy, for he has been using his real name, earns his bread and cheese by writing those incendiary social articles that my brother recently had reason to bemoan in these very rooms. There is a living to be made by exposing the shambles of British civilization known as Whitechapel, and for the more audacious members of the press, it is not unheard of to investigate in disguise if a better story is to be gained.

“The day before Martha Tabram’s murder was a Bank Holiday, and an already tumultuous metropolis was thus flooded with the idle, the curious, and the hedonistic. The promise of street markets and fireworks rendered the day a special one for the working classes, and any keen journalist would have been wise to attend. You, Mr. Dunlevy, rented the attire of a grenadier private for a few shillings, hid a notebook somewhere on your person, and sallied forth in hopes of garnering a compelling story.

“As they are a sociable set and inclusive of their own, it was not long before you fell in with a group of soldiers recently granted leave. Their failure to see through your ruse can be explained only by your being very cautious or their being very drunk, and I believe a combination of both factors enabled you to succeed. Together you stumbled from public house to public house, and as the evening drew on, you found yourself nearly as intoxicated and venturous as they.

“By all accounts, the most gregarious fellow of the regiment was one Sergeant Johnny Blackstone, known to all his fellows as a good sort when on duty but an absolute hellion when drunk. Not knowing anything of his character, you continued in his company long after his closer comrades thought it best to quit him, for he was notorious for starting brawls at the slightest provocation.

“At the Two Brewers public house, you made the acquaintance of Martha Tabram and an associate of hers, Pearly Poll. Pearly Poll has disappeared into the netherworld of London, but Martha Tabram has the distinction of having been the first woman Johnny Blackstone ever killed in a violent rage. Or at least, the first we know of. I’ve a good approximation of what led up to his bloody deed, but perhaps you could provide more precise, firsthand information.”

Stephen Dunlevy had grown more and more agitated during this narrative. At Holmes’s suggestion, he mopped his brow with his pocket handkerchief and nodded resolutely. “You astonish me, Mr. Holmes, for everything you’ve said is perfectly true. Knowing what you do already, I can hardly fail to oblige you; by the time we arrived at the Two Brewers, we were both in the drink, and we fell to chatting with a few of the girls. Blackstone was everything you’ve said—a very dashing, dark-haired fellow, who’d fought at Tel-el-Kebir in ’eighty-two with the Coldstream Guards. He was near to thirty, so far as I could tell, and very popular with all around him.

“I saw past the fog in my head that we’d stayed too long when a brawl broke out at the next table and Blackstone smashed a bottle against a man’s hand. We left the pub in a disgraceful state, at perhaps ten minutes to two, walking down the road with the girls for a short distance. Blackstone soon enough excused himself so he could duck into a dark crevice with Martha, and I made as if to do the same, but I’d recovered a fraction of my senses by then and sent Miss Poll on her way with a shilling for her trouble. I thought to stake out the entrance of the alley and wait for Blackstone to reappear.

“Five minutes passed, then ten. I returned to the pub to see if he’d changed his mind as I had, for the men we’d fought had gone, but as there was no sign of him, I retraced my steps. It must have been a quarter after two o’clock when a police constable coming out of the dark alleyway nearly walked right into me. I was so startled, I couldn’t think of a thing to do but maintain my charade, knowing that any admission I was not a soldier would lead to awkward questioning. I said my friend, a fellow guardsman, had gone off with a girl and that I was awaiting their return. The constable said he’d keep an eye out for any other soldiers and told me to be on my way.”

“And you took his advice, I believe. It was not until the next day, as you nursed your head and perused the papers, that you learned a woman had been stabbed thirty-nine times.”

Stephen Dunlevy nodded gravely, darting an occasional glance at Miss Monk. “It was as you say, Mr. Holmes.”

“Now we come to the more raveled thread. You determined that, no matter how important your evidence might prove to the Yard, not only were you uncertain about the role Blackstone may have played in Tabram’s death, but your own masquerade put you in such a false position as to make it impossible to consult the police. Not a very manly decision, Mr. Dunlevy, if I may say so.”

“I have these two months been working to redress my mistake,” cried Dunlevy.

“Indeed you have, for when Polly Nichols was killed nearby in a similarly violent manner, you took it upon yourself to discover Blackstone’s whereabouts.”

“He returned to the company barracks the night Tabram was killed—early in August, the seventh, I believe. But he complained of a number of ailments, behaving most irrationally, and soon fell into a low fever. He was relieved of his duties within the week and found himself free of all obligation.”

“And you very astutely decided that he may well have had something to do with the second murder, so you mounted your own investigation. By doing so, you could not only appease your conscience but further your career, for if you managed to discover Jack the Ripper, you would have made a journalistic coup never before equaled.

“It took time to contact Blackstone’s regiment. It took time to locate his friends. Indeed, you went so far as to seek out Pearly Poll to determine if she had any prior acquaintance with Blackstone. This inquiry took you to Lambeth Workhouse, Miss Poll’s occasional address, and there, through a very odd twist of fate, you observed us with Miss Monk. I must deduce that you recognized me and questioned why I was shaking hands with this young lady on the workhouse steps, for I can supply no other reason for your approaching her in a public house with a tale of murder most foul.”

“Mother of God!” exclaimed Miss Monk.

“I did recognize her,” Dunlevy conceded, flushing with colour, “and I had heard of your practice of employing…East-end associates, Mr. Holmes. Dr. Watson has written of such things. I freely admit I hoped she was an ally of yours and that I might learn something from her. But I wasn’t certain of your collaboration until after I realized she’d taken the extraordinary measure of stealing my wallet and then returning it.”

“You never did!” she gasped.

“It is no reflection on you, Miss Monk; it was expertly done. I always make certain I’ve my valuables about me when I leave a pub. I was about to demand its return when you very kindly replaced it.”

“And is that when you took to tailing me?”

“No, no!” he protested. “It was only after the night of the double murder! There you all were, in the thick of it—I thought you must have known something I did not. It was a far simpler proposition, Miss Monk, for me to follow you through the throngs of Whitechapel than to tail Mr. Holmes in the West-end. And when I learned that your only habitual destination was Baker Street, I stopped altogether, unless—that is to say, excepting certain circumstances.”

“When you’d read all the papers, or when you’d naught to do after tea,” she fumed.

“In any event,” Holmes continued, “Miss Monk was adroit enough to discern your pursuit yesterday, and I wrote you a telegram that I fancied would assure your presence here this afternoon.”

“And the contents of the telegram?” I prompted.

Stephen Dunlevy pulled a crumpled piece of paper out of his pocket and handed it to me with a wry countenance.

“‘Miss Monk has disappeared under dark circumstances; meet me at Baker Street at precisely three p.m.—Sherlock Holmes,’” I read aloud.

The lady in question stared in disbelief, at a total loss for words for the first time since I had known her.

“I am sure you will forgive me for having played a small trick on you. Your concern for Miss Monk’s well-being does you credit, Mr. Dunlevy, for all your shortcomings,” Holmes said, swinging his calculating gaze back to Dunlevy. “However, I must be satisfied on one point. You have been in correspondence with your employer throughout your stay in the East-end. Did you inform any members of the press of my own movements?”

“You refer to the article by that dreadful bounder Tavistock. I did mention your involvement to several colleagues, to my lasting regret,” Dunlevy owned with a pained expression, “but only insofar as to say your genius had anticipated the fiend’s attack.”

“And to my lasting regret, your assumption was utterly vacuous,” Holmes retorted coldly.

“Holmes, he could not possibly have—”

“Of course not, Watson. Mr. Dunlevy, excuse me for saying that I asked you here to determine whether you intend to be a help or a hindrance to this investigation henceforth.”

“I am your man, Mr. Holmes,” Dunlevy declared earnestly. “I fear my only real discovery was of his original lodgings, but immediately following the night in question, he abandoned them entirely. I should be overjoyed to offer you any assistance it is within my power to provide.”

“Splendid! Then I bid you good afternoon,” my friend said curtly, throwing open the door. “You may expect to hear from me within the week.”

Mr. Dunlevy shook my hand and bowed to Miss Monk. “I heartily apologize for the deception I’ve practiced,” he said, turning to Holmes. “I will think more carefully before engaging again in any undercover work. Good day to you all.”

When the door had shut, I ventured, “I do hope you intend to tell us how you worked it out, my dear fellow, for the sake of our mental health if nothing more.”

Holmes was tossing newspapers about to make room for other newspapers he prized more highly. “It is a simple enough chain, once one observes the incongruities. As I have said before, why should an army friend only mount a search a month after a traumatic event has passed? And why should a confidant take two months’ time merely to pinpoint his comrade’s lodgings on the night in question? On the other hand, why should a man harp upon the least sensational murder in a series of such crimes unless he truly was involved somehow? The rest was mere painstaking research. He had no acquaintance at Lambeth Workhouse, yet he questioned its inmates; he had no acquaintance with me, and yet he approached Miss Monk with a scintillating account of Tabram’s death. However, nothing proved so fruitful as my habitual scouring of the papers. I draw your attention to the Star,morning edition of September fifth, and again the fifth of October: they are pasted in my commonplace book, there on the desk.”

The volume lay open, weighted with a box of hair-trigger cartridges. I rose and examined the articles in question. “‘The City of Night; A Continuing Journal of the East End,’” I read. “‘By S. Leudvyn.’”

“A most informative diary of an undercover reporter. I’ve unearthed several others. The anagram was simple enough, but I consulted the offices to be sure I had my man.”

“You are certain that journalism was his only consideration?”

My friend dropped the editions he had gathered with an angry flourish. “I grow weary of the accusation that I have arranged a series of rendezvous between Miss Monk and London’s vilest criminal dregs, Doctor,” he exclaimed severely. “I can assure you that—”

“Begging both your pardons, but I slept poor enough with one little one’s hand in my hair and another’s foot in my gut. It were a right well-populated guest room, and I’m clean done. Oh, no,” Miss Monk assured us, rapidly making her way to the door, “the bed was intended for one, but the natives are that clever. I’m off home. I’ll see you at the usual time, gents. Keep to it, Mr. Holmes.”

When the door had shut, I turned back to my friend. “My dear chap, if I implied you held Miss Monk’s safety lightly, please believe that I am sorry for it,” said I.

Though my apology fell upon stony ground, I determined to carry on in spite of the rigidly set shoulders and deliberate complacency of London’s finest sleuth. “Is it not odd that Blackstone, if he is a cunning murderer, should enact a crime while still in Dunlevy’s company?”

“Hardly odd when one considers that Dunlevy had been plied with drinks the entire evening, perhaps purposefully, then packed off into the loving arms of Miss Pearly Poll. Blackstone would have imagined him entirely out of the way.”

“I see,” I acknowledged. “He did not know Dunlevy is a journalist, after all. Yes, that is very plausible. But Holmes—”

“What is it, Watson?” he demanded, snapping shut the edition he held.

“Dunlevy said he only continues to tail Miss Monk during special circumstances.”

“Of course he does.” Holmes pulled out a notebook and began to jot down cross-references. “He no longer tails her on the usual days, when she hails a cab and makes for Baker Street. He only tails her when she wanders, on foot and unescorted, through the labyrinthine darkness of Whitechapel.” My friend cocked an ironic eye at me and added, “Why he would do such a thing I leave to your unparalleled imagination.”

CHAPTER TWENTY The Thread

As Holmes’s investigations continued, I grew ever more certain that I knew next to nothing of what he was investigating. However, to my intense private satisfaction, every day he grew more visibly active, until, on Monday the fifteenth, he threw his sling into the fire in a fit of impatience and declared, “If Dr. Agar’s work and yours combined, my dear Watson, have not had their effect by now, then God help the British public, who are plagued with new ailments every day.”

The following morning, soon after I had dressed, I heard Holmes’s footsteps approaching my bedroom, and a brief knock preceded the man himself.

“How soon can you be in a cab?”

“Instantly. What is the matter?”

“George Lusk requests our aid in the most urgent language. Make haste, my dear fellow, for he is not a man to trifle with our time!”

When we arrived at Tollet Street, Holmes was out of the cab in a moment, bounding up the stairs and leaning against the bell. Immediately we were shown in to the same pleasant sitting room, occupied by the same palm fronds and self-important feline.

“I am very glad you both have come,” George Lusk declared, shaking our hands firmly. His lively brow was clouded with anxiety and the downward sweep of his moustache emphasized his unease. “The thing is a repulsive hoax, of course; I have no doubt it is merely a boon for those vultures of the popular press, but I thought it best to call you in.” He gestured to the rolltop desk.

Holmes reached it in an instant and lifted the slats. A strong smell, which I realized had faintly infused the room all along, permeated the atmosphere. I recognized it at once as spirits of wine, which was everywhere employed as a medical preservative and which I had often used myself during my years at university.

My friend seated himself at the desk, surveying a small box of plain cardboard, resting on the brown paper in which it had arrived. Mr. Lusk and I crowded round either shoulder to witness him open the receptacle. Inside sat a mound of glistening flesh.

“Well, Doctor?” said Holmes, glancing up at me. He pulled a pocketknife from his frock coat, opened it, and passed it to me along with the sinister box. I probed the object carefully.

“It is a portion of a kidney.”

“Nearly half, I would say from the angle of the cut and the arc of this side. Human?”

“Undoubtedly.”

“Gender? Age?”

“I could not tell you. If it is half, as you say, then the kidney is adult, but beyond that, further identification is impossible.”

“It does not appear to be injected with the formalin* used for dissection organs. Tissue preserved only in spirits of wine would inevitably deteriorate without a fixative and grow quickly useless in the classroom, so we can rule out a prank by an undergraduate. However, the ethyl alcohol it has been resting in is easily obtained.”

“This letter accompanied the organ,” Mr. Lusk indicated.

My friend first inspected the container itself, followed by the paper wrapping, before reaching for the document which explained, in the most vile terms and debased calligraphy I had ever laid eyes on, the contents of that horrid box.

From hell

Mr Lusk

Sor

I send you half the Kidne I took from one women prasarved it for you tother piece I fried and ate it was very nise I may send you the bloody knif that took it out if you only wate a whil longer.

Signed Catch me when

You can

Mishter Lusk

“Black ink, cheapest foolscap, no finger marks or other traces,” Holmes said softly. “‘From hell,’ indeed! What sort of frenzied imagination could be capable of constructing such trash?”

“It is a hoax, surely,” Mr. Lusk insisted. “Everyone knows Catherine Eddowes’s kidney was taken, after all, Mr. Holmes. It is the organ of a dog. Oh, I do beg your pardon, Dr. Watson—if human, as you say, perhaps it is a prank enacted by a roguish medical examiner.”

“It is possible,” said Holmes. “I do not think it likely. Look at this script: I detect key similarities to other samples from our quarry, but what a state he was in to pen this dark epistle! I have made a special study of handwriting, or graphology,* as it is now called by the French, but I have never seen anything so debauched as this specimen.”

“The script alone leads you to think this her kidney?”

“This scrap of flesh came from no school or university, and neither did it come from the nearby London Hospital.”

“How can you be sure?”

“When necessary, they preserve organic materials in glycerine.”

“Well, then, but it need not have come from the East-end. Surely in the West-end, many establishments—”

“The postmark, if one regards it with a lens, reveals the barest smudge of a ‘London E.’ It originated in Whitechapel.”

“Still, any mortuary could have supplied the thing.”

“Whitechapel possesses no mortuary!” Holmes snapped, his patience failing him. “It possesses a shed.”

Mr. Lusk’s features were suffused with complete astonishment. “But the crime rate in Whitechapel! The sickness, the disease…Only half the children ever grow up, Mr. Holmes. No district has greater need of a mortuary!”

“Nevertheless.”

“God in heaven, if the world knew the troubles of this district…” Mr. Lusk calmed himself through a visible effort of will and regarded us with a touching sadness.

“Watson, we have work ahead of us,” the detective declared shortly. “Mr. Lusk, may I entrust to you the task of reporting this matter to the Yard?”

“Of course, Mr. Holmes. Oh, and please do give my regards to Miss Monk!” Mr. Lusk exclaimed as we turned to leave. “I fear she may have been tormented to some degree by my offspring, but I trust she came to no lasting harm.”

Holmes was already halfway down the street before I reached him, the length of his stride more than making up for any residual weakness of constitution. Knowing him as I did, I had not expected him to proffer a single word, but to my surprise, speech fairly exploded from his gaunt frame.

“I will not be toyed with in this manner! As if we’d not already suffered intolerable lows, the sending of a preserved organ through the London Royal Mail quite strikes the final quivering nail into the coffin of this investigation.”

“My dear fellow, whatever can you mean?”

“Here we are furnished with clue after clue, missive after blood-soaked missive, and the villain has no further revealed his identity than he did when he plunged a knife in my chest,” he spat out in disgust. “Apart, of course, from its being a six-inch double-bladed dissection knife.”

“Holmes,” I protested, alarmed, “you have done all that could be expected of—”

“Of Gregson, or of Lestrade, or any of the other farcical simpletons who joined the Yard because they weren’t strong enough for hard labour or rich enough to buy a decent army commission.”

Shocked at his vehemence, I could only manage, “Surely we have made progress.”

“We are surrounded by quicksand! No footmarks, no signal traits, no traceable characteristics, merely the assurance he is enjoying his purloined organs and my cigarettes!”

“Holmes, where are we going?”

“To settle a debt,” he snarled, and not one word more did he say for the twenty minutes it took us to walk from Mile End to the throbbing artery of Whitechapel Road and then down a series of streets to a green door in a begrimed brick wall. Holmes rapped brusquely and then fell to tapping the head of his stick against his high forehead.

“Who resides here, Holmes?”

“Stephen Dunlevy.”

“Does he indeed? You have been here before?”

His answering glare was so exquisitely pained that I resolved to postpone further queries for better days.

A slatternly creature of advancing years in a meticulously preened bonnet opened the door and regarded us with the primness of the long-ruined. “How may I help you gentlemen?”

“We are here to see your lodger, Mr. Stephen Dunlevy.”

“And who are you, sir?”

“We are friends.”

“Now, this is a private establishment, gents. I can’t just allow any man from the street to harass my lodgers, if you understand me, sir.”

“Perfectly. In that case, we are here to bring charges against you for brothel keeping under Section Thirteen of the Criminal Law Amendment Act. That is, of course, unless you manage to remember we are friends of Mr. Dunlevy.”

“Why, of course!” she exclaimed. “The light must have dazzled my eyes. This way, if you please.”

We ascended a staircase draped in layers of cobweb and silt and crossed the hallway to an unmarked door. The landlady knocked.

“Come along, now, for there’s men to see you. Friends of yours, or so I’m told.” She favoured us with a sparingly toothed smile before descending out of sight beyond the staircase.

Without waiting for a response, Holmes gripped the knob and plunged inside and had seated himself in a nearby chair before our startled host, standing next to his open door, could venture to greet us.

“Though slowed by the thankless task of ascertaining your identity, Mr. Dunlevy, I have traced Johnny Blackstone back to his birthplace, his parents’ country farm, his primary school, his initial regiment, his transfer, his Egyptian service, and his disappearance. What I want to know is where he is. His regiment, his parents, and his dear sister are quite as eager to find him as I am. You are about to tell me every detail of your first encounter with Blackstone, omitting no microscopic facet no matter how trivial. I invite you, in fact, to glory in the trivial.” Holmes lit a cigarette and exhaled slowly. “This agency runs on minutiae, Mr. Dunlevy, and you must furnish me with fuel.”

So began an interrogation which lasted the better part of four hours; however, it seemed to me (and, I have no doubt, to Stephen Dunlevy) to have gone on for days. Over and over again Holmes demanded he recount his story. Dunlevy somehow managed to retain his good humour, but I watched him grow increasingly angry at himself that his indiscretions that night had so far impaired his observation.

I was leaning against the door smoking, Dunlevy sunk in an armchair with his chin in his hand, and Holmes draped across another chair with his feet propped on the low mantelpiece, when my friend resumed a line of questioning I thought had been exhausted long before.

“From the time Blackstone met Martha Tabram to the time you left the Two Brewers, how much of their conversation were you able to catch?”

“Only what I have told you, Mr. Holmes. Everyone was shouting and no one taking heed of a word.”

“It is not good enough! Cast your mind back. You really must try, Mr. Dunlevy.”

Dunlevy screwed his eyes shut in concentration, rubbing a weary hand along the bridge of his nose. “Blackstone complimented her bonnet. He called it very becoming. He insisted on paying for drinks for her, and she knew they would be fast friends. They fell to tormenting one of the other fellows—an edgy private who’d had his eye on a girl for an hour and still hadn’t spoken to her.”

“And then?”

“He talked of the Egyptian campaign.”

“The words he used?”

“I cannot recall exactly. He used exotic language, vivid pictures…There was a tale about three cobras that seemed to amuse her very much. I could barely manage to—”

Holmes sat up in his chair with an expression of burning interest. “Three cobras, you say?”

“That’s what it sounded like.”

“You are sure of the number?”

“I would be prepared to swear it was three. Remarkable he should have encountered so many at once, but I confess I know nothing of Egyptian terrain.”

Holmes leapt to his feet and steepled his fingers before his lips, his countenance frozen but his entire posture vibrating with barely contained energy. “Mr. Dunlevy, the question I am about to pose is of paramount importance. Describe to me, as precisely as possible, Blackstone’s eyes.”

“They were blue, very pale in colour,” Dunlevy faltered, attempting to rearrange his features so that they did not imply my friend was out of his senses.

“Did he seem troubled at all by the light?”

“There was little enough light in the lairs we visited. One bright lamp in the White Swan, I believe. I remember he sat with his back to it, but they never lost their colour. Even in the darkest of the gin shops you could see his pale eyes shining out at you.”

Holmes let out an exclamation of unparalleled delight. Rushing forward, he began to wring Dunlevy’s hand. “I knew you could not have been thrown in our path merely to torment us!” He retrieved his hat and stick and made a theatrical bow. “Dr. Watson, our presence is required elsewhere. Good day to you, Mr. Dunlevy!”

I raced after my friend and caught him up at the corner.

“ Nihil obstat.* It is a great stroke of luck. Stephen Dunlevy has just told us everything we need.”

“I am heartily glad of it.”

Holmes laughed. “I’ll own I was in a bit of a fit this morning, but surely you’ll overlook it if I tell you where we shall find word of Johnny Blackstone.”

“I confess that I cannot imagine any link between a man’s eyesight and his Egyptian exploits.”

“You, like Dunlevy, think the reference to three cobras a relic of foreign wars, then?”

“What else could it possibly mean?”

“As a medical man, the constriction of his pupils even during levels of very low illumination ought to suggest something to you.”

“On the contrary—cobra venom is a neurotoxin working on the muscles of the diaphragm and could have nothing to do with photosensitivity, or indeed any ocular symptom.”

“As usual, my dear fellow, you are both correct and misled.” He whistled stridently for a fortuitous hansom which had just rolled into view. “It will all be clear to you in a few minutes’ time, when I have introduced you to the Three Cobras, possibly the least savoury opium den in the whole of Limehouse.”