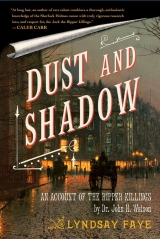

Текст книги "Dust and Shadow"

Автор книги: Lyndsay Faye

Жанры:

Криминальные детективы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

CHAPTER FIVE We Procure an Ally

We arrived home in time to witness young Hawkins’s final victory over the most abundant cold luncheon I had ever seen the good-hearted Mrs. Hudson produce. After entrusting him to a hesitant but financially approachable cabbie, we sat down to a comparable feast ourselves, which Holmes picked at for perhaps three minutes before allowing his fork to dangle momentarily between his slender fingers and then tossing it in disdain upon the china.

“It is like trying to build a pyramid out of sand,” he stated contemptuously. “The dashed bits won’t hold together. I cannot believe that London has suddenly generated three separate and equally brutal killers, all roaming about Whitechapel having their way. No more is it possible that a gang of roughs could perform their perverse acts secretly within such a densely populated terrain, not to mention fit within the confines of the Hanbury Street yard. The odds against such notions are simply astronomical.” He rose abruptly. “I am going out, Watson. If these crimes are linked, then the women are linked. We do not even know the identity of our latest victim. It is ludicrous to theorize in such an abyss.”

“When shall you return?” I called as he disappeared into his bedroom.

“The answer to that conundrum, friend Watson, I could not even begin to guess,” came his reply.

“If you should need me—”

“Never fear. I’ll scale a tree and raise the flag. England expects that every man will do his duty.” With a nod and a wave, the unofficial investigator departed; I did not see him again that day.

The events in question left me in such a state of unease that I spent much of the night staring at my ceiling. When morning at long last lifted her golden head above the brickwork of the neighbouring houses, I was seized with an irresistible urge to get out of doors. Thankfully, I had given my word to a young medical friend that I would look in on an invalid patient of his, as he had left London for the weekend and would not return until Monday. I am quite certain that old Mrs. Thistlecroft was taken aback by my strenuous advice on no account to allow castor oil through her bedroom window, nor to forsake her daily dose of cold draughts. Mercifully, I did her no harm, as she brooked no traffic with the foolish or distracted, and I very narrowly avoided being thrown out on my ear with the ringing declaration that my friend Anstruther should soon hear of her treatment at my hands.

Making my way back up Oxford Street, I stopped for a copy of the Times,to see what progress Holmes had made. I swiftly found the column, as the papers were concerned with little else:

Annie Chapman, alias“Sivvey”—a name she had received in consequence of living with a sieve maker—was the widow of a man who had been a soldier, and from whom, until about 12 months ago, when he died, she had been receiving 10s. a week. She was one of the same class as Mary Ann “Polly” Nichols, residing also in the common lodging houses of Spitalfields and Whitechapel, and is described as a stout, well-proportioned woman, as quiet, and as one who had “seen better days.” Inspector Lestrade, of Scotland Yard, who has been engaged in special inquiries surrounding the murder of Nichols, at once took up the latest investigation, the two crimes being obviously the work of the same hands. A conference with Mr. Sherlock Holmes, the well-known private consulting detective, resulted in the experts’ agreement that the crimes were connected, and that, notwithstanding many misleading statements and rumours, the murders were committed where the bodies had been found, and that no gang were the perpetrators. It is feared in many quarters that unless the culprit can speedily be captured, more outrages of a similar class will follow.

Suppressing a smile at Lestrade’s new views, I tucked the paper under my arm and dashed upstairs to see whether my friend was at home. He was not, but affixed to the mantelpiece with my letter opener was a note he had left for me:

My dear Watson,

Investigating the fascinating inner workings of the cat’s-meat trade. Might I suggest that you await the arrival of Miss Monk.

SH

I must admit to some surprise at Holmes’s afternoon appointment, and no less intrigue. I spent an hour organizing the notes I had made at Hanbury Street into some coherence, and just as I laid down my pen to stretch my legs, Mrs. Hudson peeped into the room.

“A young person to see Mr. Holmes, sir. Are you expecting her? She gives her name as Miss Monk.”

“Send her straight up, Mrs. Hudson. She is an associate of ours.”

Lifting her brows delicately, Mrs. Hudson departed. A minute later, the door burst open to reveal the petite frame of Miss Mary Ann Monk, clad this time in her own attire: a dark green cotton bodice fastened with seven or eight varieties of carefully salvaged buttons, a skillfully altered man’s vest, and a midnight blue figured coat which hung to the knee, revealing a profusion of skirts, the outermost an ancient green wool so much abused that it had deepened nearly to black. Her riot of hair was pinned and then tied back over the crown of her head with a narrow strip of cotton fabric, but it nevertheless showed signs of impending escape. She approached me and extended her hand.

“Very pleased to see you again, Miss Monk. Do sit down.”

She did so, with a poise implying that she had not always been in her present circumstances. However, she was soon up again, perusing the assortment of curiosities above the fireplace and tossing an ancient spearhead nervously from hand to hand before speaking.

“I can’t say as I know why Mr. Holmes asked me to tea, nor how he come to know I was lodged at Miller’s Court. Though,” she added, smiling, “I think Mr. Holmes does what he likes and knows a great many things he oughtn’t.”

“What you say is very true. I am afraid I cannot answer any of your questions just yet, though it is certainly within my purview to ring for tea.”

At the mention of this precious article, a gleam appeared in her eye, which she quickly buried beneath studied nonchalance. “Well, if Mr. Holmes won’t be offended. He did say four o’clock in the telegram, and I’m before my time. First wire in British history to be delivered to Miller’s Court, like enough, and I’d still his money in my boot for paying the shoful. Don’t know the last time I’ve ridden insidea cab. You could have knocked my pals down with a feather. I waved out the window as I left.” Miss Monk laughed at the thought, and I could not help but join her.

“As Mr. Holmes has charged me with keeping you comfortable until he arrives, I think immediate refreshment is in order, don’t you?” I inquired, ringing the bell.

“Tea,” she said languorously. “Served in good china, I’d wager. Maybe even with cream. Oh, I am sorry, Dr. Watson,” she exclaimed, embarrassed. “Here, then, I’ve some tea in my pocket—just enough for three, I’d say. I had a run of luck last night. Should you like some?” Miss Monk produced a small leather pouch stuffed with dusty brown tea leaves, obviously an item of immense value to its owner.

“I am sure Holmes would prefer not to accept such a courtesy when you are a guest in our home, Miss Monk. Here is Mrs. Hudson now.”

Our landlady had indeed arrived, hefting a tray loaded with far more than the usual sandwiches required by Holmes’s erratic appetite and my discretion.

“It’s just as it was when I was a girl! I remember trays like these—tiered, ain’t that the word? Shall I pour, Dr. Watson?”

“By all means.” I smiled. “But do tell me, if you are not offended by the question, where were you born, Miss Monk?”

“Here in England,” she replied readily, making surprisingly elegant work of pouring the tea. “Mum was Italian, and Dad convinced her to throw her own family over and put her hand in with him. We had land once, but there was a disputed will…I was seven, if I remember rightly. Lord knows but it’s been ages since they both died. Cholera struck ’em down, one right after t’other. So here I am. Staggered at the sight of a decent tea.”

Though she smiled, I could not help but feel I had awkwardly broached a painful subject, and I had just opened my mouth in hopes an appropriate reply would emerge when Sherlock Holmes entered our sitting room.

“Halloa, halloa, what have we here?” he cried. “Miss Monk, you are most welcome. I have spent my time—well, perhaps I had better just splash some water on my face and be with you directly. I have been in a most pernicious environment.” He disappeared for a brief period but returned looking quite his orderly self again and plunged a lean hand into the slipper which held his tobacco.

“You will excuse me, I am sure, if I light my pipe. Did this spearhead interest you? It is a very ancient object, recently the instrument of death in a very modern crime.”

All of Miss Monk’s nerves, which I flatter myself had been largely dispelled, returned at the sight of my friend. “Thank you kindly for the tea, Mr. Holmes, but I’ve already answered all the questions I could, honest I have.”

“Undoubtedly. However, I did not invite you here to interrogate you. I brought you here to ask you plainly, Miss Monk, do you feel as if you could play a part in bringing the Whitechapel killer to justice?”

“Me?” she exclaimed. “How do you expect me to help? Polly’s cold in her grave, and the other lass had her innards mucked all over the parish.”

“And I fear I must inform you, Miss Monk, that I suspect this man may continue killing until the very day that he is caught,” replied the detective. “Though it is undoubtedly in all our interests to find him quickly, I imagined your feelings for Polly Nichols might encourage you to take a more active role.”

“Really, Holmes, I cannot imagine what sort of role you mean,” I countered.

Holmes drew upon his pipe languidly, always a sign of concentration rather than of relaxation. “I propose that you enter my employment, Miss Monk. I could spend the lion’s share of my days building connections in the East-end, keeping the pulse of fresh rumour ever at my fingertips, but I am afraid I cannot afford to stretch myself so thinly. You, however, are placed in an ideal position to go unnoticed, hearing and seeing everything.”

“You’d pay me to nose? Nose on what?” Miss Monk asked incredulously.

“On the neighbourhood itself. There’s no more lucrative cover for flushing a bird than the local alehouses at which you are already known and trusted.”

Miss Monk’s emerald eyes widened considerably at Holmes’s remarkable suggestion. “But why ask a ladybird like me to spy on the Chapel? Why not use some jack or other, what’s trained to sniff about?”

“I do not think I need employ other detectives. You, Miss Monk, see more than those fellows do already. As for terms, here is an advance of five pounds for expenses, and I imagine you would do well enough on a pound a week, is that not so?”

“Would I!” cried Miss Monk, her pointed chin descending at the generous figure. “But if I’m to pitch over my daily work, how am I to explain the chink?”

Holmes considered the question. “I imagine you could tell your companions that you have arrested the attentions of a poetic and passionate West-end client who has determined to engage your services under more exclusive terms.”

This suggestion elicited a ringing peal of laughter from Miss Monk. “You’re mad, you know. I’ll be rubbish—who am I to help hunt down the Knife?”

“Is that what they’re calling him?” My friend smiled. “Miss Monk, I can think of no one better suited to assist me.”

“Well,” she said stoutly, “I’m all for it if you are. If I can help lay a hand on Polly’s killer, it’s a job well done. No more smatter hauling for me this month, gents.”

“Income garnered through theft of handkerchiefs,” Holmes murmured under his breath.

“Ah, yes,” said I. “Quite so.”

We settled that Miss Monk would confine her investigations to the neighbourhoods of Whitechapel and Spitalfields, taking note of all local speculation. She would then report to Holmes twice weekly at Baker Street, under the pretext of paying calls upon her gentleman suitor. It was a determined Miss Monk, I noted, who descended our stairs to the cab waiting at the street corner.

Holmes threw himself upon the settee as I cast about for a means to light my pipe.

“She’ll prove useful, Watson, mark my words,” he declared, tossing me a matchbox. “ Alis volat propriis,* if I am not very much mistaken.”

“She’ll come to no harm, Holmes?”

“I should hope not. Alehouses are safe as churches by comparison with the murky alleys of her usual vocation. By the way, I came by a spot of success this morning.”

“I meant to inquire. What the deuce has cat’s meat to do with the matter?”

“Although I have not yet ascertained whether Annie Chapman, for so I have discovered she was called, was tied in any way to Polly Nichols or Martha Tabram, she was nevertheless ill-starred enough to fall victim to the Whitechapel killer, who made off with possibly the most repellent token I have ever heard spoken of.”

“I recall as much.”

“Well, then. What does that aforementioned token suggest to you?” Holmes’s eyes shone and the twitch of his brow gave me every hope that he was onto something.

“Do you mean to tell me you have found a clue?”

“My dear Watson, flex your mental musculature and see if you can make note of the remarkable fact which Lestrade, in his horror at the proceedings, has seemingly not yet grasped.”

“Every one of these vile facts is remarkable enough to me.”

“Oh, come, Watson, do make an effort. You are the killer. You dispatch your victim. You open her up, and remove her womb.”

“Well, of course!” I exclaimed. “What the devil did he do with it?”

“Bravo, Watson. The blackguard certainly did not amble down the lane with it in his trouser pocket.”

“But the cat’s meat?”

“This morning I found, because I was looking for it, a quantity of cat’s meat hidden beneath one of the stones in the yard of number twenty-seven, which must make all clear for you. You recall my interest in whether Mrs. Hardyman of twenty-nine Hanbury Street, ground floor, front room, had done a brisk business that morning?”

“I see! He purchased a package of cat’s meat.”

“Excellent, my dear Watson. You make me feel as if I were there.”

“He then hid the cat’s meat, placing the organ in the bloody package and making off down the street, free of suspicion.”

“You shall master the deductive arts yet, my boy.”

“But who is he?”

“Mrs. Hardyman’s riveting description was as follows: ‘A sort of regular-looking chap, middle-sized, very polite in his ways.’ She thought she had seen him before but could not recall where or whether she had ever previously sold him cat’s meat. You see our earlier inference is confirmed; he is apparently not a man who imposes himself upon the senses. And this cat’s-meat business indicates premeditation yet again, which is more than a little disturbing to my mind.”

“What the devil could he have wanted with such a gruesome prize?”

“I cannot begin to tell you. Well, at any rate, it is certainly the best lead we’ve dug up, and while Miss Monk pans the silt, we shall see if we cannot add some fresh particulars to this shabbily dressed fellow, whose taste in souvenirs is as indecent as it is incomprehensible.”

CHAPTER SIX A Letter to the Boss

The next morning, I was interrupted whilst stoking the fading morning fire in our sitting room by a resounding exclamation of disgust from Sherlock Holmes, who sat transfixed with a newspaper upon the breakfast table in front of him and an arrested coffeepot in his hand.

“Confound the man! Well, if the fool wishes to waste his labour on squaring the circle, as it is said, we can do nothing about it.”

“What has happened?”

“Lestrade has arrested John Pizer, against all tattered remains of rational thought.”

“At your suggestion, surely,” I reminded him.

“I wired him there was nothing in it!” Holmes protested. “Even the Evening Standardcannot credit his having anything to do with the matter.”

“And what more have the gutter press to say on the subject?”

Snapping the paper emphatically, he read, “‘It would seem that there is, haunting the slums and purlieus of Whitechapel, some obscene creature in human guise, whose hands are stained with the “gory witness” of a whole series of butcheries’…ha!…‘shocking perversion of Nature…bestial wretch…unquenchable as the taste of a man-eating tiger for human flesh.’”

“For heaven’s sake, my dear fellow.”

“I didn’t write it,” he said mischievously.

A brief knock at the door heralded the approach of our pageboy. “You’ve a telegram, Holmes.” I could not help but smile as my eyes scanned the correspondence. “Mr. Lusk is now the acting president of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee. He sends his allegiance and his warm regards.”

“Capital! Well, I am gratified to see that some of these active fellows are actually applying their energies in a beneficial direction. We shall follow their example, my good man—we must learn more about this purchaser of cat’s meat, and with all possible haste.”

But throughout the week that followed, Holmes met with only the most limited success. Despite all our efforts, as the killer had left no physical trace, we could not identify the man who had vanished that morning into the cold September air. The Vigilance Committee, a truly robust organization from the start, swiftly organized neighbourhood watches and nightly patrols, but they encountered few hazards beyond the outbreaks of vicious antiforeign mobs, who took it upon themselves to beat any hapless immigrant whose “sly looks” or “crooked demeanour” proved his degenerate nature. Every citizen of Whitechapel from the most devout charity worker to the lowest cracksman cried out in chorus that no native Englishman could ever have killed a poor woman so.

Annie Chapman was buried secretly on Friday the fourteenth of September, at the same paupers’ cemetery where Polly Nichols had been given back to the infinite little over a week before. “Pulvis et umbra sumus,”Holmes remarked that night, staring into the fire with his long arms cast thoughtfully about his drawn-up knees. “You and I, Watson, Annie Chapman, even the revered Horace himself—dust and the shadow cast by it, merely that and nothing more.”

Though Holmes lamented during the weeks following Annie Chapman’s death that the trails grew colder with every nervous twitch of the clock, I knew he was gratified that at least his investment in Miss Mary Ann Monk had proven fruitful. As Holmes followed slender leads to their barren conclusions, we anticipated eagerly our meetings with Miss Monk, who appeared to relish her new occupation. My friend, whose casual charm all too often masked cold, incisive professionalism, seemed genuinely pleased to see her, while I looked forward warmly to the boisterous air of enthusiasm with which she infused our discouraged sitting room.

On the twenty-third of September, the Polly Nichols inquest ended in resounding ignorance. Upon the following Wednesday, the selfsame coroner concluded the Annie Chapman inquest with the novel suggestion that a rapacious medical student had killed her and stolen the organ, intending it for sale to an unscrupulous American doctor. This news, reported earnestly in the Timesthe next day, resulted in Holmes’s raving silently at the ceiling before locating his hair trigger, falling despairingly into his chair, and tattooing a small crown in bullets above the previously rendered intertwined VRto the left of our fireplace.

“My dear fellow, might I suggest that any further adornment of Her Majesty’s initials would be disrespectfully garish?” Carefully orienting myself behind Holmes, I opened the windows in anticipation of Miss Monk’s imminent arrival.

“You question my loyalty to the Crown?”

“I question your employment of firearms.”

Holmes sighed ruefully and replaced the gun in his desk. “Miss Monk is due any moment. Perhaps she brings further evidence against the diabolical American purveyor of female reproductive organs.”

“Really, Holmes!”

The detective smiled briefly by way of apology and then, catching the unmistakable tread of a slightly built woman ascending a staircase in heavy work boots, crossed our sitting room and threw open the door.

“Lor’, what’s this, then? A fire?” Miss Monk demanded, coughing. She had indulged part of her weekly pound in a bit of silvery ribbon to line the bottom of her coat, I observed. I also noted, not without some satisfaction, that her tiny frame had taken on a decidedly less skeletal appearance.

“Holmes occasionally mistakes our sitting room for a firing range,” I replied wryly. “Do sit down, Miss Monk.”

“Had a drop of the lush, have you?” Miss Monk nodded. “I’d a friend once was known to shoot at naught when he’d made himself good and comfortable with a bottle of gin. You’ve something better, haven’t you—whiskey, I suppose?”

I hid my own smile by clearing some newspapers off the settee, but Holmes laughed outright and strode to the sideboard for glasses.

“Your remark seems to me absolutely inspired. Whiskey and soda for all concerned is, I think, very much in order.”

“Bollocks to this cold,” Miss Monk said contentedly when she had been seated by the fire clutching her glass of spirits. “Could freeze the eyes out of your head. At any rate, gents, I’ve earned my billet this week.”

“How so?” queried Holmes, leaning back and closing his eyes.

“I’ve traced the soldier, that’s what.”

Holmes sat up again, the picture of zeal. “Which soldier do you mean?”

“The pal. The cove what lost his mate, like enough to have stabbed that first judy, Martha Tabram.”

“Excellent! Tell me everything. You may well have wired me over a discovery of this magnitude, you know.”

“Happened this morning,” she replied with pride. “Dropped by the Knight’s Standard for a cup of max* to open me eyes as I do every morning, earning my keep all the while as you know. It’s a right thick, smoky place, and near empty at that time, but there’s a soldier I could barely make out, off in the corner. I begin to think I’ll wander over and chat him up a bit, but before I can shift, he’s spied me, seemingly, and gets up to join me at the bar. He’s a well-built chap, strong jaw, dark moustache turned up at the ends, with blue eyes and sandy brown hair.

“‘Hullo there,’ says he.

“‘Hullo yourself,’ says I. ‘Share a glass of gin with a lonesome girl?’

“‘I can’t imagine you’re ever lonesome for long,’ says he, smiling.

“I think to myself, if that’s all he’s after, he can move straight along, for I’ve no need of his business. But he must have seen I weren’t pleased and says quick and eager, ‘It was only meant for a compliment, Miss.’

“‘That’s all right, then. I’ll let you sit here till you’ve thought of a better one.’

“‘A very generous offer,’ says he, and sits.

“The conversation starts out slow, but seeing as we’re drinking max and he’s a proper flat, soon enough he’s chattering his nob off. ‘Got discharged just last week and came straight back to London. The whole lot of us were in town last near two months ago,’ says he. ‘There’s a pal of mine I’m keen to find.’

“‘Your mate owes you something?’ I ask.

“‘Nothing like that. But I have to lay my hands on him all the same.’

“‘But why?’

“‘He’s committed murder, you see.’

“Well, you can bet your last tanner I wasn’t letting him out of my sight now until I’d heard the whole tale. I look as shocked as I can, which is no hard lay seeing as I’m fairly staggered.

“‘Murder! What’d he do it for, then? Lost his head during a caper? Or was it a fight?’

“‘I’m afraid it’s far worse. My friend is a very dangerous fellow.’

“‘What, one of a gang?’

“He shakes his head and peers down his nose thoughtfully and says, ‘He acted alone, so far as I know.’

“I sit and wait for him to go on, and when he sees I’m hanging on his every word, he says, ‘You see, when we were last here, a woman was killed. My friend did it, or so I believe. And I’m very sorry to say that he got away.’

“‘You gave me a turn!’ I gasp, for I can’t help but think he’s talking of Martha Tabram, and suddenly I feel cold all over at the sight of him. ‘You ought to be ashamed of yourself, telling such stories when every judy in the Chapel’s fair sick over rumours of the Knife.’

“‘You don’t believe me, but every word of it’s true,’ says he. ‘I had a friend in my regiment. Never knew a better mate than him. He was a fine chap all round but had a temper like you’ve never seen. He met a girl here when last we were in town. It all began harmlessly enough. We went from pub to pub—but then he took her into an alleyway with him. I waited. I knew something was wrong when they weren’t back in a few minutes, but I waited all the same. I’ve already told you the end of it, anyway. Since that terrible night, I’ve not laid eyes on Johnny Blackstone, but I am going to find him if it’s the last thing I ever do.’

“Then he’s quiet for a spell. Soon enough he comes back to himself and notices me sitting there. ‘I haven’t frightened you, have I? I’ve no wish to burden you, but it’s heavy on my mind. My duty’s clear enough: he has to be found, and found quickly.’”

“One moment,” Holmes interrupted. “This guardsman—he believes his missing comrade to be responsible for the other murders as well?”

“Seemed troubled enough by the question,” replied Miss Monk calmly. “So I tries to draw him out, but I must have looked so rattled that he thinks he’s said enough and shuts it. Keeps telling me he’s sorry to have upset me. Had the devil of a time after that to even get his name. I says to him, looking a mite faint, ‘I must go home…,’ and he takes my arm and leads me out. I stagger on the doorstep and clutch at his jacket, and he helps me up like a proper gentleman, but by then I’d tooled the reader straight from out his gropus.”

“You lifted his wallet?” Holmes repeated incredulously. I must confess that I was grateful for the interjection.

“I beg your pardon,” she blushed. “Been at it so long, it’s a job not to voker Romeny.* That’s right—I pinched it. His name is Stephen Dunlevy,” she finished.

Holmes and I looked at each other in amazement. “Miss Monk,” said my friend, “you have done splendidly.”

She smiled, a little shyly. “It was a ream job right enough, and I’m proud of it.”

“However, I fear that you may have burned a significant bridge by stealing this fellow’s wallet.”

“Oh, never fear for that, Mr. Holmes,” she replied, laughing. “I put it back.”

At that moment we detected the sound of a muffled argument on the ground floor. Before we could guess as to its source, the singular sound of two feet accompanied by two crutches approached our sitting room at an alarming speed, and seconds later one of Holmes’s most peculiar acquaintances tore into the room like a winter’s gale.

Mr. Rowland K. Vandervent of the Central News Agency was approximately thirty years of age and exceptionally tall, nearly on par with Holmes himself, but he appeared much less so as he was bent at the waist from a crippling bout with polio when he was a child. He had an unruly mop of shockingly blond, virtually white hair, and I fear that this combined with his frail legs and crutch-assisted gait gave me the perpetual impression that he had just fallen victim to electric shock. He had once watched Holmes spar, I believe, when a spectator at an amateur boxing match, and Mr. Vandervent, who held my friend in the highest regard, occasionally sent wires to inform Holmes of stories which had just been broken to the agency. Nevertheless, I was startled at the sight of the man himself, wheezing after his rapid ascent of the stairs. His right arm, clad as always in a shabby pinstriped frock coat, held aloft a small piece of paper.

“Mr. Holmes, I’ve a matter to discuss with you which can brook no delay. However, I encountered serious impediments downstairs. You’ve a most uncouth and tenacious landlady. By the Lord Harry! Here she is again. Madam, I have explained that it is a matter of profound indifference to me whether he is engaged or no.”

“It is all right, Mrs. Hudson,” cried Holmes. “Mr. Vandervent has had scant exposure to polite society. Do excuse us, if you will.”

Mrs. Hudson wiped her hands upon the tea towel she was holding, regarded Mr. Vandervent as she would a venomous insect, and returned downstairs to her cooking.

“Mr. Vandervent, you never call upon me but you upset the fragile balance of our household. Dr. Watson you know, of course. May I introduce our new associate, Miss Mary Ann Monk. Now, whatever it is you’ve got there, let us have a look at it.”

We all crowded around the table and examined the curious missive Mr. Vandervent had brought with him. I read the letter aloud, which was penned with vivid red ink and went in this manner:

Dear Boss

I keep on hearing the police have caught me but they wont fix me just yet. I have laughed when they look so clever and talk about being on the right track. That joke about Leather Apron gave me real fits. I am down on whores and I shant quit ripping them till I do get buckled. Grand work the last job was. I gave the lady no time to squeal. How can they catch me now. I love my work and want to start again. You will soon hear of me with my funny little games. I saved some of the proper red stuff in a ginger beer bottle over the last job to write with but it went thick like glue and I cant use it. Red ink is fit enough I hope ha. ha. The next job I do I shall clip the ladys ears off and send to the police officers just for jolly wouldnt you. Keep this letter back till I do a bit more work, then give it out straight. My knife’s so nice and sharp I want to get to work right away if I get a chance. Good luck.

Yours truly

Jack the Ripper

Don’t mind me giving the trade name

Wasn’t good enough to post this before I got all the red ink off my hands curse it. No luck yet. They say I’m a doctor now—ha ha

“It is hardly the natural correspondence of our readership, as you can see,” stated Mr. Vandervent, collapsing unceremoniously into a chair. “A bit more about repealing the corn laws and a bit less about clipping off ladies’ ears, and I should not have troubled you.”