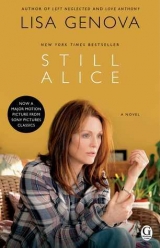

Текст книги "Still Alice"

Автор книги: Lisa Genova

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

Dinner with their friends Bob and Sarah. It was on her calendar.

“I forgot. I have Alzheimer’s.”

“I had absolutely no idea where you were, if you were lost. You have to start carrying your cell phone with you at all times.”

“I can’t bring it with me when I run, I don’t have any pockets.”

“Then duct tape it to your head, I don’t care, I’m not going through this every time you forget you’re supposed to show up somewhere.”

She followed him into the living room. He sat down on the couch, held his drink in his hand, and wouldn’t look up at her. The beads of sweat on his forehead matched those on his sweaty glass of scotch. She hesitated, then sat on his lap, hugged him hard around his shoulders with her hands touching her own elbows, her ear against his, and let it all out.

“I’m so sorry I have this. I can’t stand the thought of how much worse this is going to get. I can’t stand the thought of looking at you someday, this face I love, and not knowing who you are.”

She traced the outline of his jaw and chin and the creases of his sorely out of practice laugh lines with her hands. She wiped the sweat from his forehead and the tears from his eyes.

“I can barely breathe when I think about it. But we have to think about it. I don’t know how much longer I have to know you. We need to talk about what’s going to happen.”

He tipped his glass back, swallowed until there was nothing left, and then sucked a little more from the ice. Then he looked at her with a scared and profound sorrow in his eyes that she’d never seen there before.

“I don’t know if I can.”

APRIL 2004

As smart as they were, they couldn’t cobble together a definitive, long-term plan. There were too many unknowns to simply solve for x, the most crucial of those being, How fast will this progress? They’d taken a year’s sabbatical together six years ago to write From Molecules to Mind, and so they were each a year away from being eligible for taking another. Could she make it that long? So far, they’d decided that she’d finish out the semester, avoid travel whenever possible, and they’d spend the entire summer at the Cape. They could only imagine as far as August.

And they agreed to tell no one yet, except for their children. That unavoidable disclosure, the conversation they had agonized over the most, would unfold that very morning over bagels, fruit salad, Mexican frittata, mimosas, and chocolate eggs.

They hadn’t all been together for Easter in a number of years. Anna sometimes spent that weekend with Charlie’s family in Pennsylvania, Lydia had stayed in L.A. the last several years and was somewhere in Europe before that, and John had attended a conference in Boulder a few years back. It had taken some work to persuade Lydia to come home this year. In the middle of rehearsals for her play, she’d claimed she couldn’t afford the interruption or the flight, but John had convinced her that she could spare two days and paid for her airfare.

Anna declined a mimosa and a Bloody Mary and instead washed down the caramel eggs she’d been eating like popcorn with a glass of iced water. But before anyone could harbor suspicions of pregnancy, she launched into the details of her impending intrauterine insemination procedure.

“We saw a fertility specialist over at the Brigham, and he can’t figure it out. My eggs are healthy, and I’m ovulating each month, and Charlie’s sperm are fine.”

“Anna, really, I don’t think they want to hear about my sperm,” said Charlie.

“Well, it’s true, and it’s so frustrating. I even tried acupuncture, and nothing. Except my migraines are gone. So at least we know that I should be able to get pregnant. I start FSH injections on Tuesday, and next week I inject myself with something that will release my eggs, and then they’ll inseminate me with Charlie’s sperm.”

“Anna,” said Charlie.

“Well, they will, and so hopefully, I’ll be pregnant next week!”

Alice forced a supportive smile, caging her dread behind her clenched teeth. The symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease didn’t manifest until after the reproductive years, after the deformed gene had unwittingly been passed on to the next generation. What if she’d known that she carried this gene, this fate, in every cell of her body? Would she have conceived these children or taken precautions to prevent them? Would she have been willing to risk the random roll of meiosis? Her amber eyes, John’s aquiline nose, and her presenilin-1. Of course, now, she couldn’t imagine her life without them. But before she had children, before the experience of that primal and previously inconceivable kind of love that came with them, would she have decided it would be better for everyone not to? Would Anna?

Tom walked in, with apologies for being late and without his new girlfriend. It was just as well. Today should be just the family. And Alice couldn’t remember her name. He made a beeline for the dining room, likely worried that he’d missed out on the food, then returned to the living room with a grin on his face and a plate heaping with some of everything. He sat on the couch next to Lydia, who had her script in her hand and her eyes closed, silently mouthing her lines. They were all there. It was time.

“Your dad and I have something important we need to talk to you about, and we wanted to wait until we had all three of you together.”

She looked to John. He nodded and squeezed her hand.

“I’ve been experiencing some difficulties with my memory for some time now, and in January, I was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease.”

The clock on the fireplace mantel ticked loudly, like someone had turned its volume up, the way it sounded when no one else was in the house. Tom sat frozen with a forkful of frittata midway between his plate and mouth. She should have waited until he’d finished eating his brunch.

“Are they sure it’s Alzheimer’s? Did you get a second opinion?” he asked.

“She had genetic screening. She has the presenilin-1 mutation,” said John.

“Is it autosomal dominant?” asked Tom.

“Yes.”

He said more to Tom, but only with his eyes.

“What does that mean? Dad, what did you just tell him?” Anna asked.

“It means we have a fifty percent chance of getting Alzheimer’s disease,” said Tom.

“What about my baby?”

“You’re not even pregnant,” said Lydia.

“Anna, if you have the mutation, it’s the same for your children. Each child you have would have a fifty percent chance of inheriting it, too,” said Alice.

“So what do we do? Do we go get tested?” asked Anna.

“You can,” said Alice.

“Oh my god, what if I have it? And then my baby could have it,” said Anna.

“There’ll probably be a cure by the time any of our kids would need it,” said Tom.

“But not in time for us, is that what you’re saying? So my kids will be fine, but I’ll be a mindless zombie?”

“Anna, that’s enough!” John snapped.

His jaw clenched, and his face flushed. A decade ago, he would’ve sent Anna to her room. Instead, he gave Alice’s hand a hard squeeze and jiggled his leg. In so many ways, he’d become powerless.

“Sorry,” said Anna.

“It’s very likely that there’ll be a preventative treatment by the time you’re my age. That’s one of the reasons to know if you have the mutation. If you do, you might be able to go on a medication well before you’re symptomatic and, hopefully, you never will be,” said Alice.

“Mom, what kind of treatment do they have now, for you?” asked Lydia.

“Well, they have me on antioxidant vitamins and aspirin, a statin, and two neurotransmitter drugs.”

“Are those going to keep the Alzheimer’s from getting any worse?” asked Lydia.

“Maybe, for a little while, they don’t really know for sure.”

“What about what’s in clinical trials?” asked Tom.

“I’m looking into that now,” said John.

John had begun talking to clinicians and scientists in Boston who researched the molecular etiology of Alzheimer’s, getting their perspectives on the relative promise of the therapies in the clinical pipeline. John was a cancer cell biologist, not a neuroscientist, but it wasn’t a huge leap for him to understand the cast of molecular criminals run amok in another system. They all spoke the same language—receptor binding, phosphorylation, transcriptional regulation, clathrin-coated pits, secretases. Like owning a membership card to the most exclusive club, being from Harvard gave him instant credibility with and access to the most respected thought leaders in Boston’s Alzheimer’s research community. If a better treatment existed or might exist soon, John would find it for her.

“But Mom, you seem perfectly fine. You must’ve caught this really early on, I wouldn’t even know anything was wrong,” said Tom.

“I knew,” said Lydia. “Not that she had Alzheimer’s, but that something was wrong.”

“How?” asked Anna.

“Like sometimes she doesn’t make any sense on the phone, and she repeats herself a lot. Or she doesn’t remember something I said five minutes ago. And she didn’t remember how to make the pudding at Christmas.”

“How long have you noticed this?” asked John.

“At least a year now.”

Alice couldn’t trace it quite that far back herself, but she believed her. And she sensed John’s humiliation.

“I have to know if I have this. I want to get tested. Don’t you guys want to get tested?” asked Anna.

“I think living with the anxiety of not knowing would be worse for me than knowing, even if I have it,” said Tom.

Lydia closed her eyes. Everyone waited. Alice entertained the absurd idea that she had either resumed memorizing her lines or fallen asleep. After an uncomfortable silence, she opened her eyes and took her turn.

“I don’t want to know.”

Lydia always did things differently.

IT WAS ODDLY QUIET IN William James Hall. The usual chatter of students in the hallways—asking, arguing, joking, complaining, bragging, flirting—was missing. Spring Reading Period typically precipitated the sudden sequestering of students from the campus at large into dormitory rooms and library cubicles, but that didn’t begin for another week. Many of the cognitive psychology students were scheduled to spend an entire day observing functional MRI studies in Charlestown. Maybe that was today.

Whatever the reason, Alice relished the opportunity to get a lot of work done without interruption. She had opted not to stop at Jerri’s for tea on the way to her office and wished now that she had. She could use the caffeine. She read through the articles in the current Linguistics Journal, she put together this year’s version of the final exam for her motivation and emotion class, and she answered all previously neglected emails. All without the phone ringing or a knock on the door.

She was home before she realized that she’d forgotten to go to Jerri’s. She still wanted that tea. She walked into the kitchen and put the kettle on the stove. The microwave clock read 4:22 a.m.

She looked out the window. She saw darkness and her reflection in the glass. She was wearing her nightgown.

Hi Mom,

The IUI didn’t work. I’m not pregnant. I’m not as upset as I thought I’d be (and Charlie seems almost relieved). Let’s hope my other test comes back negative as well. Our appointment for that is tomorrow. Tom and I will come over after and let you and Dad know the results.

Love,

Anna

THE ODDS OF THEM BOTH being negative for the mutation descended from unlikely to remote when they still weren’t home an hour after Alice had anticipated their arrival. If they were both negative, it would have been a quick appointment, a “you’re both fine,” “thank you very much,” and out-the-door appointment. Maybe Stephanie was just running late today. Maybe Anna and Tom had sat in the waiting room much longer than Alice had allowed for in her mind.

The odds crashed from remote to infinitesimal when they finally walked through the front door. If they were both negative, they would have just blurted it out or it would have sprung, wild and jubilant, from their facial expressions. Instead, they muscled what they knew beneath the surface as they moved into the living room, stretching out the time of Life Before This Happened as long as possible, the time before they’d have to unleash the hideous information they so obviously held.

They sat side by side on the couch, Tom on the left and Anna on the right, like they had in the backseat of the car when they were kids. Tom was a lefty and liked the window, and Anna didn’t mind the middle. They sat closer now than they ever did then, and when Tom reached over and held her hand, she didn’t shriek, “Mommm, Tommy’s touching me!”

“I don’t have the mutation,” said Tom.

“But I do,” said Anna.

After Tom was born, Alice remembered feeling so blessed, that she had the ideal—one of each. It took twenty-six years for that blessing to deform into a curse. Alice’s facade of stoic parental strength crumbled, and she started to cry.

“I’m sorry,” she said.

“It’s going to be okay, Mom. Like you said, they’re going to find a preventative treatment,” said Anna.

When Alice thought about it later, the irony was striking. Outwardly, at least, Anna appeared to be the strongest. She did most of the consoling. And yet, it didn’t surprise her. Anna was the child who most mirrored their mother. She had Alice’s hair, coloring, and temperament. And her mother’s presenilin-1.

“I’m going to go ahead with the in vitro. I already talked with my doctor, and they’re going to do a preimplantation genetic diagnosis on the embryos. They’re going to test a single cell from each of the embryos for the mutation and only implant ones that are mutation-free. So we’ll know for sure that my kids won’t ever get this.”

It was a solid piece of good news. But while everyone else continued to savor it, the taste turned slightly bitter for Alice. Despite her self-reproach, she envied Anna, that she could do what Alice couldn’t—keep her children safe from harm. Anna would never have to sit opposite her daughter, her firstborn, and watch her struggle to comprehend the news that she would someday develop Alzheimer’s. She wished that these kinds of advances in reproductive medicine had been available to her. But then the embryo that had developed into Anna would’ve been discarded.

According to Stephanie Aaron, Tom was okay, but he didn’t look it. He looked pale, shaken, fragile. Alice had imagined that a negative result for any of them would be a relief, clean and simple. But they were a family, yoked by history and DNA and love. Anna was his older sister. She’d taught him how to snap and blow gum bubbles, and she always gave him her Halloween candy.

“Who’s going to tell Lydia?” asked Tom.

“I will,” said Anna.

MAY 2004

Alice first thought of peeking inside the week after she was diagnosed, but she didn’t. Fortune cookies, horoscopes, tarot cards, and assisted living homes couldn’t tempt her interest. Although closer to it every day, she was in no hurry to glimpse her future. Nothing in particular happened that morning to fuel her curiosity or the courage to go have a look inside the Mount Auburn Manor Nursing Center. But today, she did.

The lobby did nothing to intimidate her. An ocean scene watercolor hung on the wall, a faded Oriental carpet lay on the floor, and a woman with heavily made up eyes and short, licorice black hair sat behind a desk angled toward the front door. The lobby could almost be mistaken for that of a hotel, but the slight medicinal smell and the lack of luggage, concierge, and general coming and going weren’t right. The people staying here were residents, not guests.

“Can I help you?” the woman asked.

“Um, yes. Do you care for Alzheimer’s patients here?”

“Yes, we have a unit specifically dedicated to patients with Alzheimer’s. Would you like to have a look at it?”

“Yes.”

She followed the woman to the elevators.

“Are you looking for a parent?”

“I am,” Alice lied.

They waited. Like most of the people they ferried, the elevators were old and slow to respond.

“That’s a lovely necklace,” said the woman.

“Thank you.”

Alice placed her fingers on the top of her sternum and rubbed the blue paste stones on the wings of her mother’s art nouveau butterfly necklace. Her mother used to wear it only on her anniversary and to weddings, and like her, Alice had reserved it exclusively for special occasions. But there weren’t any formal affairs on her calendar, and she loved that necklace, so she’d tried it on one day last month while wearing a pair of jeans and a T-shirt. It had looked perfect.

Plus, she liked being reminded of butterflies. She remembered being six or seven and crying over the fates of the butterflies in her yard after learning that they lived for only a few days. Her mother had comforted her and told her not to be sad for the butterflies, that just because their lives were short didn’t mean they were tragic. Watching them flying in the warm sun among the daisies in their garden, her mother had said to her, See, they have a beautiful life. Alice liked remembering that.

They exited onto the third floor and walked down a long, carpeted hallway through a set of unmarked double doors and stopped. The woman gestured back to the doors as they shut automatically behind them.

“The Alzheimer’s Special Care Unit is locked, meaning you can’t go beyond these doors without knowing the code.”

Alice looked at the keypad on the wall next to the door. The numbers were arranged individually upside down and ordered backward from right to left.

“Why are the numbers like that?”

“Oh, that’s to prevent the residents from learning and memorizing the code.”

It seemed like an unnecessary precaution. If they could remember the code, they wouldn’t need to be here, would they?

“I don’t know if you’ve experienced this yet with your parent, but wandering and nighttime restlessness are very common behaviors with Alzheimer’s. Our unit allows the residents to wander about at any time, but safely and without the risk of getting lost. We don’t tranquilize them at night or restrict them to their rooms. We try to help them maintain as much freedom and independence as possible. It’s something we know is important to them and to their families.”

A small, white-haired woman in a pink and green floral housecoat confronted Alice.

“You’re not my daughter.”

“No, sorry, I’m not.”

“Give me back my money!”

“She didn’t take your money, Evelyn. Your money’s in your room. Check your top dresser drawer, I think you put it there.”

The woman eyed Alice with suspicion and disgust, but then followed the advice of authority and shuffled in her dirty white terry-cloth slippers back into her room.

“She has a twenty-dollar bill she keeps hiding because she’s worried someone will steal it. Then, of course, she forgets where she put it and accuses everyone of taking it. We’ve tried to get her to spend it or put it in the bank, but she won’t. At some point, she’ll forget she owns it, and that’ll be the end of it.”

Safe from Evelyn’s paranoid investigation, they proceeded unimpeded to a common room at the end of the hallway. The room was populated with elderly people eating lunch at round tables. Upon taking a closer look, Alice realized that the room was filled with elderly women.

“There are only three men?”

“Actually, only two out of the thirty-two residents are men. Harold comes every day to eat meals with his wife.”

Perhaps reverting to the cootie rules of childhood, the two men with Alzheimer’s disease sat together at their own table, apart from the women. Walkers crowded the spaces between the tables. Many of the women sat in wheelchairs. Most everyone had thinning white hair and sunken eyes magnified behind thick glasses, and they all ate in slow motion. There was no socializing, no conversation, not even between Harold and his wife. The only sounds other than the noises of eating came from a woman who sang while she ate, her internal needle skipping on the title line of “By the Light of the Silvery Moon” over and over. No one protested or applauded.

By the light of the silvery moon.

“As you might’ve guessed, this is our dining and activities room. Residents have breakfast, lunch, and dinner here at the same times every day. Predictable routines are important. Activities are here as well. There’s bowling and beanbag toss, trivia, dancing and music, and crafts. They made these adorable birdhouses this morning. And we have someone read the newspaper to them every day to keep them up on current events.”

By the light

“There’s plenty of opportunity for our residents to keep their bodies and minds as engaged and enriched as possible.”

of the silvery moon.

“And family members and friends are always welcome to come and participate in any of the activities and can join their loved one for any of the meals.”

Aside from Harold, Alice saw no other loved ones. No other husbands, no wives, no children or grandchildren, no friends.

“We also have a highly trained medical staff should any of our residents require additional care.”

By the light of the silvery moon.

“Do you have any residents here under the age of sixty?”

“Oh no, the youngest is I think seventy. The average age is about eighty-two, eighty-three. It’s rare to see someone with Alzheimer’s younger than sixty.”

You’re looking at one right now, lady.

By the light of the silvery moon.

“How much does all of this cost?”

“I can give you a packet of information on the way out, but as of January, the Alzheimer’s Special Care Unit rate runs at two hundred eighty-five dollars a day.”

Alice did the rough math in her head. About a hundred thousand dollars a year. Multiply that by five, ten, twenty years.

“Can I answer anything else for you?”

By the light.

“No, thanks.”

She followed her tour guide back to the locked double doors and watched her type in the code.

0791925

She didn’t belong here.

IT WAS THE RAREST OF days in Cambridge, the kind of mythical day that New Englanders dreamed about but each year came to doubt the true existence of—a sunny, seventy-degree spring day. A Crayola blue sky, finally-don’t-need-a-coat spring day. A day not to be wasted sitting in an office, especially if you had Alzheimer’s.

She deviated a couple of blocks southeast of the Yard and walked into Ben & Jerry’s with the giddy thrill of a teenager playing hooky.

“I’ll have a triple-scoop Peanut Butter Cup in a cone, please.”

Hell, I’m on Lipitor.

She beheld her giant, heavy cone as if it were an Oscar, paid with a five-dollar bill, dropped the change in the Tips for College jar, and continued on toward the Charles River.

She’d converted to frozen yogurt, a supposedly healthier alternative, many years ago and had forgotten how thick and creamy and purely enjoyable ice cream was. She thought about what she had just seen at the Mount Auburn Manor Nursing Center as she licked and walked. She needed a better plan, one that didn’t include her playing beanbag toss with Evelyn in the Alzheimer’s Special Care Unit. One that didn’t cost John a fortune to keep alive and safe a woman who no longer recognized him and who, in the most important ways, he didn’t recognize either. She didn’t want to be here at that point, when the burdens, both emotional and financial, grossly outweighed any benefit of sticking around.

She was making mistakes and struggling to compensate for them, but she felt sure that her IQ still fell at least a standard deviation above the mean. And people with average IQs didn’t kill themselves. Well, some did, but not for reasons having to do with IQ.

Despite the escalating erosion of her memory, her brain still served her well in countless ways. For example, at this very moment, she ate her ice cream without dripping any of it onto the cone or her hand by using a lick-and-turn technique that had become automatic to her as a child and was probably stored somewhere near the information for how to ride a bike and how to tie a shoe. Meanwhile, she stepped off the curb and crossed the street, her motor cortex and cerebellum solving the complex mathematical equations necessary to move her body to the other side without falling over or getting hit by a passing car. She recognized the sweet smell of narcissus and a brief waft of curry emanating from the Indian restaurant on the corner. With each lick, she savored the delicious tastes of chocolate and peanut butter, demonstrating the intact activation of her brain’s pleasure pathways, the same ones required for enjoying sex or a good bottle of wine.

But at some point, she would forget how to eat an ice-cream cone, how to tie her shoe, and how to walk. At some point, her pleasure neurons would become corrupted by an onslaught of aggregating amyloid, and she’d no longer be capable of enjoying the things she loved. At some point, there would simply be no point.

She wished she had cancer instead. She’d trade Alzheimer’s for cancer in a heartbeat. She felt ashamed for wishing this, and it was certainly a pointless bargaining, but she permitted the fantasy anyway. With cancer, she’d have something that she could fight. There was surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. There was the chance that she could win. Her family and the community at Harvard would rally behind her battle and consider it noble. And even if defeated in the end, she’d be able to look them knowingly in the eye and say good-bye before she left.

Alzheimer’s disease was an entirely different kind of beast. There were no weapons that could slay it. Taking Aricept and Namenda felt like aiming a couple of leaky squirt guns in the face of a blazing fire. John continued to probe into the drugs in clinical development, but she doubted that any of them were ready and capable of making a significant difference for her, else he would already have been on the phone with Dr. Davis, insisting on a way to get her on them. Right now, everyone with Alzheimer’s faced the same outcome, whether they were eighty-two or fifty, resident of the Mount Auburn Manor or full professor of psychology at Harvard University. The blazing fire consumed all. No one got out alive.

And while a bald head and a looped ribbon were seen as badges of courage and hope, her reluctant vocabulary and vanishing memories advertised mental instability and impending insanity. Those with cancer could expect to be supported by their community. Alice expected to be outcast. Even the well-intentioned and educated tended to keep a fearful distance from the mentally ill. She didn’t want to become someone people avoided and feared.

Accepting the fact that she did indeed have Alzheimer’s, that she could only bank on two unacceptably effective drugs available to treat it, and that she couldn’t trade any of this in for some other, curable disease, what did she want? Assuming the in vitro procedure worked, she wanted to live to hold Anna’s baby and know it was her grandchild. She wanted to see Lydia act in something she was proud of. She wanted to see Tom fall in love. She wanted one more sabbatical year with John. She wanted to read every book she could before she could no longer read.

She laughed a little, surprised at what she’d just revealed to herself. Nowhere in that list was there anything about linguistics, teaching, or Harvard. She ate her last bite of cone. She wanted more sunny, seventy-degree days and ice-cream cones.

And when the burden of her disease exceeded the pleasure of that ice cream, she wanted to die. But would she quite literally have the presence of mind to recognize it when those curves crossed? She worried that the future her would be incapable of remembering and executing this kind of plan. Asking John or any of her children to assist her with this in any way was not an option. She’d never put any of them in that position.

She needed a plan that committed the future her to a suicide she arranged for now. She needed to create a simple test, one that she could self-administer every day. She thought about the questions Dr. Davis and the neuropsychologist had asked her, the ones she already couldn’t answer last December. She thought about what she still wanted. Intellectual brilliance wasn’t required for any of them. She was willing to go on living with some serious holes in short-term memory.

She removed her BlackBerry from her baby blue Anna William bag, a birthday gift from Lydia. She wore it every day, slung over her left shoulder, resting on her right hip. It had become an indispensable accessory, like her platinum wedding ring and running watch. It looked great with her butterfly necklace. It contained her cell phone, her BlackBerry, and her keys. She took it off only to sleep.

She typed:

Alice, answer the following questions:

1. What month is it?

2. Where do you live?

3. Where is your office?

4. When is Anna’s birthday?

5. How many children do you have?

If you have trouble answering any of these, go to the file named “Butterfly” on your computer and follow the instructions there immediately.

She set the alarm to vibrate and to appear as a recurring reminder every morning on her appointment calendar at 8:00, no end date. She realized that there were a lot of potential problems with this design, that it was by no means foolproof. She just hoped she opened “Butterfly” before she became that fool.

SHE PRACTICALLY RAN TO CLASS, worried that she was most certainly late, but nothing had started without her when she got there. She took an aisle seat, four rows back, left of center. A few students trickled in through the doors at the back of the room, but for the most part, the class was there, ready. She looked at her watch. 10:05. The clock on the wall agreed. This was most unusual. She kept herself busy. She looked over the syllabus and skimmed her notes from last class. She made a to-do list for the rest of the day:

Lab

Seminar

Run

Study for final

Time, 10:10. She tapped her pen to the tune of “My Sharona.”

The students stirred, becoming restless. They checked notebooks and the clock on the wall, they flipped through textbooks and shut them, they booted up laptops and clicked and typed. They finished their coffees. They crinkled wrappers belonging to candy bars and chips and various other snacks and ate them. They chewed pen caps and fingernails. They twisted their torsos to search the back of the room, they leaned to consult friends in other rows, they raised eyebrows and shrugged shoulders. They whispered and giggled.