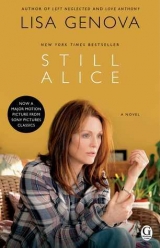

Текст книги "Still Alice"

Автор книги: Lisa Genova

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

FEBRUARY 2005

She slumped into the chair next to John, across from Dr. Davis, emotionally weary and intellectually tapped. She’d been taking various neuropsychological tests in that little room with that woman, the woman who administered the neuropsychological tests in the little room, for a torturously long time. The words, the information, the meaning in the woman’s questions and in Alice’s own answers were like soap bubbles, the kind children blew out of those little plastic wands, on a windy day. They drifted away from her quickly and in dizzying directions, requiring enormous strain and concentration to track. And even if she managed to actually hold a number of them in her sight for some promising duration, it was invariably too soon that pop! they were gone, burst without obvious cause into oblivion, as if they’d never existed. And now it was Dr. Davis’s turn with the wand.

“Okay, Alice, can you spell the word water backwards for me?” he asked.

She would have found this question trivial and even insulting six months ago, but today, it was a serious question to be tackled with serious effort. She felt only marginally worried and humiliated by this, not nearly as worried and humiliated as she would’ve felt six months ago. More and more, she was experiencing a growing distance from her self-awareness. Her sense of Alice—what she knew and understood, what she liked and disliked, how she felt and perceived—was also like a soap bubble, ever higher in the sky and more difficult to identify, with nothing but the thinnest lipid membrane protecting it from popping into thinner air.

Alice spelled water forward first, to herself, extending the five fingers on her left hand, one for each letter, as she did.

“R.” She folded down her pinkie. She spelled it forward to herself again, stopping at her ring finger, which she then folded down.

“E.” She repeated the same process.

“T.” She held her thumb and pointer finger like a gun. She whispered, “A, W,” to herself.

“A, W.”

She smiled, her left hand raised in a victorious fist, and looked at John. He spun his wedding ring and gave a dispirited smile.

“Good job,” said Dr. Davis. He smiled widely and seemed impressed. Alice liked him.

“Now, I’d like you to point to the window after you touch your right cheek with your left hand.”

She lifted her left hand to her face. Pop!

“I’m sorry, can you tell me the directions again?” asked Alice, her left hand still poised in front of her face.

“Sure,” Dr. Davis obliged knowingly, like a parent who let a child get away with peeking at the top card in a game of cards or inching across the start line before yelling “go.” “Point to the window after you touch your right cheek with your left hand.”

Her left hand on her right cheek before he finished talking, she jerked her right arm at the window as fast as she could and let out a huge exhale.

“Good, Alice,” said Dr. Davis, smiling again.

John offered no praise, no hint of pleasure or pride.

“Okay, now I’d like you to tell me the name and address I asked you to remember earlier.”

The name and address. She had a loose sense of it, like the feeling of awakening from a night’s sleep and knowing she’d had a dream, maybe even knowing it was about a particular thing, but no matter how hard she thought about it, the details of the dream eluded her. Gone forever.

“It’s John Somebody. You know, you ask me this every time, and I’ve never been able to remember where that guy lives.”

“Okay, let’s take a guess. Was it John Black, John White, John Jones, or John Smith?”

She had no idea but didn’t mind playing along.

“Smith.”

“Does he live on East Street, West Street, North Street, or South Street?”

“South Street.”

“Was the town Arlington, Cambridge, Brighton, or Brookline?”

“Brookline.”

“Okay, Alice, last question, where’s my twenty-dollar bill?”

“In your wallet?”

“No, earlier, I hid a twenty-dollar bill somewhere in the room, do you remember where I put it?”

“You did this while I was here?”

“Yes. Any ideas at all come to mind? I’ll let you keep it if you find it.”

“Well, if I’d known that, I would’ve been sure to figure out a way to remember it.”

“I’m sure you would’ve. Any idea where it is?”

She saw the focus of his stare deviate to her right, just over her shoulder, for the briefest moment before settling back on her. She twisted around. Behind her, there was a whiteboard on the wall with three words scrawled on it in red marker: Glutamate. LTP. Apoptosis. The red marker lay on a tray at the bottom, right next to a folded twenty-dollar bill. Delighted, she stepped over to the whiteboard and claimed her prize.

Dr. Davis chuckled. “If all my patients were as smart as you, I’d go broke.”

“Alice, you can’t keep that, you saw him look at it,” said John.

“I won it,” said Alice.

“It’s okay, she found it,” said Dr. Davis.

“Should she be like this after only a year and being on medication?” asked John.

“Well, there are probably a few things going on here. Her illness probably started long before she was diagnosed last January. She and you and your family and her colleagues probably disregarded any number of symptoms as fluke, or normal, or chalked them up to stress, not enough sleep, too much to drink, and on and on. This could’ve gone on easily for a year or two or longer.

“And she’s incredibly bright. If the average person has, say for simplicity, ten synapses that lead to a piece of information, Alice could easily have fifty. When the average person loses those ten synapses, that piece of information is inaccessible to them, forgotten. But Alice can lose those ten and still have forty other ways of getting to the target. So her anatomical losses aren’t as profoundly and functionally noticeable at first.”

“But by now, she’s lost a lot more than ten,” said John.

“Yes, I’m afraid she has. Her recent memory is now falling in the bottom three percent of those able to complete the tests, her language processing has degraded considerably, and she’s losing self-awareness, all as we’d unfortunately expect to see.

“But she’s also incredibly resourceful. She used a number of inventive strategies today to answer questions correctly that she couldn’t actually remember correctly.”

“But there were a lot of questions that she couldn’t answer correctly, regardless,” said John.

“Yes, that’s true.”

“It’s just getting so much worse, so quickly. Can we up the dosage of either the Aricept or the Namenda?” asked John.

“No, she’s at the maximum dosage already for both. Unfortunately, this is a progressive, degenerative disease with no cure. It gets worse, despite any medication we have right now.”

“And it’s clear she’s either getting the placebo or this Amylix drug doesn’t work,” said John.

Dr. Davis paused as if considering whether to agree or disagree with this.

“I know you’re discouraged. But I’ve often seen unexpected periods of plateau, where it seems to stall, and this can last for some time.”

Alice closed her eyes and pictured herself standing solidly in the middle of a plateau. A beautiful mesa. She could see it, and it was worth hoping for. Could John see it? Could he still hope for her, or had he already given up? Or worse, did he actually hope for her rapid decline, so he could take her, vacant and complaisant, to New York in the fall? Would he choose to stand with her on the plateau or push her down the hill?

She folded her arms, unfolded her crossed legs, and planted her feet flat on the floor.

“Alice, are you still running?” asked Dr. Davis.

“No, I stopped a while ago. Between John’s schedule and my lack of coordination—I can’t seem to see curbs or bumps in the road, and I misjudge distances. I had some terrible falls. Even at home, I keep forgetting about the raised thingy in all the doorways, and I trip into every room I go in. I’ve got tons of bruises.”

“Okay, John, I would either remove the doorway thingies or paint them a contrasting color, something bright, or cover them in brightly colored tape, so Alice can notice them. Otherwise, they just blend into the floor.”

“All right.”

“Alice, tell me about your support group,” said Dr. Davis.

“There are four of us. We meet once a week for a few hours at each other’s houses, and we email each other every day. It’s wonderful, we talk about everything.”

Dr. Davis and that woman in that little room had asked her a lot of probing questions today, questions designed to measure the precise level of destruction inside her head. But no one understood what was still alive inside her head better than Mary, Cathy, and Dan.

“I want to thank you for taking the initiative and filling the obvious gap we have in our support system here. If I get any new early stage or early-onset patients, can I tell them how to get in touch with you?”

“Yes, please do. You should also tell them about DASNI. It’s the Dementia Advocacy and Support Network International. It’s an online forum for people with dementia. I’ve met over a dozen people there, from all over the country and Canada and the UK and Australia. Well, I’ve never actually met them, it’s all online, but I feel like I know them and they know me more intimately than many of the people I’ve known my whole life. We don’t waste any time, we don’t have enough of it. We talk about the stuff that matters.”

John shifted in his seat and jiggled his leg.

“Thank you, Alice, I’ll add that website to our standard packet of information. How about you, John? Have you yet talked with our social worker here or gone to any of the caregivers’ support group meetings?”

“No, I haven’t. I’ve had coffee a couple of times with the spouses of her support group people, but otherwise, no.”

“You might want to consider getting some support yourself. You’re not the one with the disease, but you’re living with it, too, by living with Alice, and it’s hard on the caregivers. I see the toll it takes every day with the family members who come in. There’s Denise Daddario, the social worker, here and the MGH Caregivers’ Support Group, and I know that the Massachusetts Alzheimer’s Association has many local caregiver groups. The resources are there for you, so don’t hesitate if you need them.”

“All right.”

“Speaking of the Alzheimer’s Association, Alice, I just received their program for the annual Dementia Care Conference, and I see you’re giving the opening plenary presentation,” said Dr. Davis.

The Dementia Care Conference was a national meeting for professionals involved in the care of people with dementia and their families. Neurologists, general practice physicians, geriatric physicians, neuropsychologists, nurses, and social workers all gathered in one place to exchange information on approaches to diagnosis, treatment, and patient care. It sounded similar to Alice’s support group and DASNI, but bigger and for those without dementia. This year’s meeting was to be held next month in Boston.

“Yes,” said Alice. “I meant to ask, will you be there?”

“I will, I’ll be sure to be in the front row. You know, they’ve never asked me to give a plenary presentation,” said Dr. Davis. “You’re a brave and remarkable woman, Alice.”

His compliment, genuine and not patronizing, was just the boost her ego needed after having been so ruthlessly pummeled by so many tests today. John spun his ring. He looked at her with tears in his eyes and a clenched smile that confused her.

MARCH 2005

Alice stood at the podium with her typed speech in her hand and looked out at the people seated in the hotel’s grand ballroom. She used to be able to eyeball an audience and guess with an almost psychic accuracy the number of people in attendance. It was a skill she no longer possessed. There were a lot of people. The organizer, whatever her name was, had told her that over seven hundred people were registered for the conference. Alice had given many talks to audiences that size and larger. The people in her audiences past had included distinguished Ivy League faculty, Nobel Prize winners, and the world’s thought leaders in psychology and language.

Today, John sat in the front row. He kept looking back over his shoulder as he repeatedly wrung his program into a tight tube. She hadn’t noticed until just now that he was wearing his lucky gray T-shirt. He usually reserved it for only his most critical lab result days. She smiled at his superstitious gesture.

Anna, Charlie, and Tom sat next to him, talking to one another. A few seats down sat Mary, Cathy, and Dan with their husbands and wife. Positioned front and center, Dr. Davis sat ready with his pen and notebook. Beyond them sat a sea of health professionals dedicated to the care of people with dementia. This might not be her biggest or most prestigious audience, but of all the talks she’d given in her life, she hoped this one would have the most powerful impact.

She ran her fingers back and forth across the smooth, gemmed wings of her butterfly necklace, which sat, as if perched, on the knobby tip of her sternum. She cleared her throat. She took a sip of water. She touched the butterfly wings one more time, for luck. Today’s a special occasion, Mom.

“Good morning. My name is Dr. Alice Howland. I’m not a neurologist or general practice physician, however. My doctorate is in psychology. I was a professor at Harvard University for twenty-five years. I taught courses in cognitive psychology, I did research in the field of linguistics, and I lectured all over the world.

“I am not here today, however, to talk to you as an expert in psychology or language. I’m here today to talk to you as an expert in Alzheimer’s disease. I don’t treat patients, run clinical trials, study mutations in DNA, or counsel patients and their families. I am an expert in this subject because, just over a year ago, I was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

“I’m honored to have this opportunity to talk with you today, to hopefully lend some insight into what it’s like to live with dementia. Soon, although I’ll still know what it is like, I’ll be unable to express it to you. And too soon after that, I’ll no longer even know I have dementia. So what I have to say today is timely.

“We, in the early stages of Alzheimer’s, are not yet utterly incompetent. We are not without language or opinions that matter or extended periods of lucidity. Yet we are not competent enough to be trusted with many of the demands and responsibilities of our former lives. We feel like we are neither here nor there, like some crazy Dr. Seuss character in a bizarre land. It’s a very lonely and frustrating place to be.

“I no longer work at Harvard. I no longer read and write research articles or books. My reality is completely different from what it was not long ago. And it is distorted. The neural pathways I use to try to understand what you are saying, what I am thinking, and what is happening around me are gummed up with amyloid. I struggle to find the words I want to say and often hear myself saying the wrong ones. I can’t confidently judge spatial distances, which means I drop things and fall down a lot and can get lost two blocks from my home. And my short-term memory is hanging on by a couple of frayed threads.

“I’m losing my yesterdays. If you ask me what I did yesterday, what happened, what I saw and felt and heard, I’d be hard-pressed to give you details. I might guess a few things correctly. I’m an excellent guesser. But I don’t really know. I don’t remember yesterday or the yesterday before that.

“And I have no control over which yesterdays I keep and which ones get deleted. This disease will not be bargained with. I can’t offer it the names of the United States presidents in exchange for the names of my children. I can’t give it the names of the state capitals and keep the memories of my husband.

“I often fear tomorrow. What if I wake up and don’t know who my husband is? What if I don’t know where I am or recognize myself in the mirror? When will I no longer be me? Is the part of my brain that’s responsible for my unique ‘meness’ vulnerable to this disease? Or is my identity something that transcends neurons, proteins, and defective molecules of DNA? Is my soul and spirit immune to the ravages of Alzheimer’s? I believe it is.

“Being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s is like being branded with a scarlet A. This is now who I am, someone with dementia. This was how I would, for a time, define myself and how others continue to define me. But I am not what I say or what I do or what I remember. I am fundamentally more than that.

“I am a wife, mother, and friend, and soon to be grandmother. I still feel, understand, and am worthy of the love and joy in those relationships. I am still an active participant in society. My brain no longer works well, but I use my ears for unconditional listening, my shoulders for crying on, and my arms for hugging others with dementia. Through an early-stage support group, through the Dementia Advocacy and Support Network International, by talking to you today, I am helping others with dementia live better with dementia. I am not someone dying. I am someone living with Alzheimer’s. I want to do that as well as I possibly can.

“I’d like to encourage earlier diagnosis, for physicians not to assume that people in their forties and fifties experiencing memory and cognition problems are depressed or stressed or menopausal. The earlier we are properly diagnosed, the earlier we can go on medication, with the hope of delaying progression and maintaining a footing on a plateau long enough to reap the benefits of a better treatment or cure soon. I still have hope for a cure, for me, for my friends with dementia, for my daughter who carries the same mutated gene. I may never be able to retrieve what I’ve already lost, but I can sustain what I have. I still have a lot.

“Please don’t look at our scarlet A’s and write us off. Look us in the eye, talk directly to us. Don’t panic or take it personally if we make mistakes, because we will. We will repeat ourselves, we will misplace things, and we will get lost. We will forget your name and what you said two minutes ago. We will also try our hardest to compensate for and overcome our cognitive losses.

“I encourage you to empower us, not limit us. If someone has a spinal cord injury, if someone has lost a limb or has a functional disability from a stroke, families and professionals work hard to rehabilitate that person, to find ways to cope and manage despite these losses. Work with us. Help us develop tools to function around our losses in memory, language, and cognition. Encourage involvement in support groups. We can help each other, both people with dementia and their caregivers, navigate through this Dr. Seuss land of neither here nor there.

“My yesterdays are disappearing, and my tomorrows are uncertain, so what do I live for? I live for each day. I live in the moment. Some tomorrow soon, I’ll forget that I stood before you and gave this speech. But just because I’ll forget it some tomorrow doesn’t mean that I didn’t live every second of it today. I will forget today, but that doesn’t mean that today didn’t matter.

“I’m no longer asked to lecture about language at universities and psychology conferences all over the world. But here I am before you today, giving what I hope is the most influential talk of my life. And I have Alzheimer’s disease.

“Thank you.”

She looked up from her speech for the first time since she began talking. She hadn’t dared to break eye contact with the words on the pages until she finished, for fear of losing her place. To her genuine surprise, the entire ballroom was standing, clapping. It was more than she had hoped for. She’d hoped for two simple things—not to lose the ability to read during the talk and to get through it without making a fool of herself.

She looked at the familiar faces in the front row and knew without a doubt that she had far exceeded those modest expectations. Cathy, Dan, and Dr. Davis beamed. Mary was dabbing her eyes with a handful of pink tissues. Anna clapped and smiled without once stopping to wipe the tears that streamed down her face. Tom clapped and cheered and looked like he could barely keep himself from running up to hug and congratulate her. She couldn’t wait to hug him, too.

John stood tall and unabashed in his lucky gray T-shirt, with an unmistakable love in his eyes and joy in his smile as he applauded her.