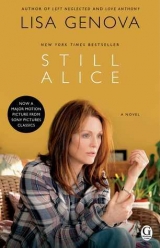

Текст книги "Still Alice"

Автор книги: Lisa Genova

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

MORE PRAISE FOR LISA GENOVA’S POIGNANT AND ILLUMINATING DEBUT NOVEL,

STILL ALICE

“After I read Still Alice, I wanted to stand up and tell a train full of strangers, ‘You have to get this book.’…I couldn’t put it down…. Still Alice is written not from the outside looking in, but from the inside looking out…. [It] isn’t only about dementia. It’s about Alice, a woman beloved by her family and respected by her colleagues, who in the end, is still Alice, not just her disease.”

–Beverly Beckham, The Boston Globe

“Still Alice is a heartbreakingly real depiction of a woman’s descent into early Alzheimer’s, so real, in fact, that it kept me from sleeping for several nights. I couldn’t put it down. As a part-time caregiver to a parent with dementia, I can say that Dr. Genova’s depiction seems spot-on, from the subtle changes in everyday life to the ultimate changes in both patient and family. Still Alice is a story that must be told.”

–Brunonia Barry, New York Times bestselling author of The Lace Reader

“At once agonizing and engrossing, this tale of brilliant Harvard psychology professor Alice Howland’s descent into dementia grabs you from the first misfired neuron. With the clinician’s precision of language and the master storyteller’s easy eloquence, Lisa Genova shines a searing spotlight on this Alice’s surreal wonderland. You owe it to yourself and your loved ones to read this book. It will inform you. It will scare you. It will change you.”

–Julia Fox Garrison, author of Don’t Leave Me This Way

“I wish I could have read Lisa Genova’s masterpiece before my dad passed away following a ten-year struggle with Alzheimer’s. I would have better understood and appreciated what was unfolding in his confused and ravaged mind…. This book is as important as it is impressive and will grace the lives of those affected by this dread disease for generations to come.”

–Phil Bolsta, author of Sixty Seconds

“An intensely intimate portrait of Alzheimer’s seasoned with highly accurate and useful information about this insidious and devastating disease.”

–Dr. Rudolph E. Tanzi, coauthor of Decoding Darkness: The Search for the Genetic Causes of Alzheimer’s Disease

“Genova has brilliantly captured the subjective experience in this intimate story…. Touching and informative.”

–Daniel Kuhn, author of Alzheimer’s Early Stages: First Steps for Families, Friends, and Caregivers

“An ironic look at complicated family relationships, our hopes for future generations, and the essence of life…. Whether or not you or someone in your family has dementia, Still Alice is a great read.”

–The Tangled Neuron

“Powerful, insightful, tragic, inspirational…and all too true. Genova has the great gift of insight, imagination, and expression that allows her to pry open the fortress door and tell a story from a perspective seldom spoken…. Her revealing insights into these deeply personal experiences show true empathy and understanding not only of cognitive neuroscience and dementia, but also of the human condition.”

–Alireza Atri, M.D., Ph.D., Neurologist, Massachusetts General Hospital, Memory Disorders Unit

“The experience of Alzheimer’s disease is a process of discovery. Readers, along with Alice, are artfully and realistically led through this process, moving from the questions and concerns that accompany unexplained memory difficulties to the experience of diagnosis and the impact of Alice’s changing needs on relationships with her family and colleagues.”

–Peter Reed, Ph.D., Senior Director of Programs, Alzheimer’s Association

“Dementia is dark and ugly. Only a writer with a mastery of neuroscience and the grit, the empathy, of an actor with Meisner training could get both the facts and the feelings right—the way I live it daily. Still Alice is a laser precise light into the lives of people with dementia and the people who love them.”

–Carole Mulliken, cofounder of DementiaUSA

Pocket Books

Pocket Books

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2007, 2009 by Lisa Genova

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Pocket Books Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

POCKET and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Information from the Activities of Daily Living Questionnaire was taken with permission from “The Record of Independent Living” by Sandra Weintraub, Ph.D., in the American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementia, Vol. 1, No. 2, 35–39 (1986), a SAGE publication.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Genova, Lisa.

Still Alice / Lisa Genova.

p. c.m.

1. Alzheimer’s disease—Fiction. 2. Women college teachers—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3607.E55S75 2008

813'.6—dc22 2008030986

ISBN-13: 978-1-4391-5703-9

ISBN-10: 1-4391-5703-0

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

http://www.SimonSays.com

In Memory of Angie

For Alena

Acknowledgments

I’m deeply grateful to the many people I’ve come to know through the Dementia Advocacy and Support Network International and DementiaUSA, especially Peter Ashley, Alan Benson, Christine Bryden, Bill Carey, Lynne Culipher, Morris Friedell, Shirley Garnett, Candy Harrison, Chuck Jackson, Lynn Jackson, Sylvia Johnston, Jenny Knauss, Jaye Lander, Jeanne Lee, Mary Lockhart, Mary McKinlay, Tracey Mobley, Don Moyer, Carole Mulliken, Jean Opalka, Charley Schneider, James Smith, Jay Smith, Ben Stevens, Richard Taylor, Diane Thornton, and John Willis. Your intelligence, courage, humor, empathy, and willingness to share what was individually vulnerable, scary, hopeful, and informative have taught me so much. My portrayal of Alice is richer and more human because of your stories.

I’d especially like to thank James and Jay, who have given me so much beyond the boundaries of Alzheimer’s and this book. I am truly blessed to know you.

I’d also like to thank the following medical professionals, who generously shared their time, knowledge, and imaginations, helping me to gain a true and specific sense for how events might unfold as Alice’s dementia is discovered and progresses:

Dr. Rudy Tanzi and Dr. Dennis Selkoe for an in-depth understanding of the molecular biology of this disease

Dr. Alireza Atri for allowing me to shadow him for two days in the Memory Disorders Unit at Massachusetts General Hospital, for showing me your brilliance and compassion

Dr. Doug Cole and Dr. Martin Samuels for additional understanding of the diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer’s

Sara Smith for allowing me to sit in on neuropsychological testing

Barbara Hawley Maxam for explaining the role of the social worker and Mass General’s Caregivers’ Support Group

Erin Linnenbringer for being Alice’s genetic counselor Dr. Joe Maloney and Dr. Jessica Wieselquist for role-playing as Alice’s general practice physician

Thank you to Dr. Steven Pinker for giving me a look inside life as a Harvard psychology professor and to Dr. Ned Sahin and Dr. Elizabeth Chua for similar views from the student’s seat.

Thank you to Dr. Steve Hyman, Dr. John Kelsey, and Dr. Todd Kahan for answering questions about Harvard and life as a professor.

Thank you to Doug Coupe for sharing some specifics about acting and Los Angeles.

Thank you to Martha Brown, Anne Carey, Laurel Daly, Kim Howland, Mary MacGregor, and Chris O’Connor for reading each chapter, for your comments, encouragement, and wild enthusiasm.

Thank you to Diane Bartoli, Lyralen Kaye, Rose O’Donnell, and Richard Pepp for editorial feedback.

Thank you to Jocelyn Kelley at Kelley & Hall for being a phenomenal publicist.

An enormous thank-you to Beverly Beckham, who wrote the best review any self-published author could dream of. And you pointed the way to Julia Fox Garrison.

Julia, I cannot thank you enough. Your generosity has changed my life.

Thank you to Vicky Bijur for representing me and for insisting that I change the ending. You’re brilliant.

Thank you to Louise Burke, John Hardy, Kathy Sagan, and Anthony Ziccardi for believing in this story.

I need to thank the very large and loud Genova family for shamelessly telling everyone you know to buy your daughter’s/niece’s/cousin’s/sister’s book. You’re the best guerrilla marketers in the world!

I also need to thank the not as large but arguably just as loud Seufert family for spreading the word.

Last, I’d like to thank Christopher Seufert for technical and web support, for the original cover design, for helping me make the abstract tangible, and so much more, but mostly, for giving me butterflies.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments

SEPTEMBER 2003

OCTOBER 2003

NOVEMBER 2003

DECEMBER 2003

JANUARY 2004

FEBRUARY 2004

MARCH 2004

APRIL 2004

MAY 2004

JUNE 2004

JULY 2004

AUGUST 2004

SEPTEMBER 2004

OCTOBER 2004

NOVEMBER 2004

DECEMBER 2004

JANUARY 2005

FEBRUARY 2005

MARCH 2005

APRIL 2005

MAY 2005

JUNE 2005

SUMMER 2005

SEPTEMBER 2005

EPILOGUE

POSTSCRIPT

Readers Club Guide for Still Alice

Even then, more than a year earlier, there were neurons in her head, not far from her ears, that were being strangled to death, too quietly for her to hear them. Some would argue that things were going so insidiously wrong that the neurons themselves initiated events that would lead to their own destruction. Whether it was molecular murder or cellular suicide, they were unable to warn her of what was happening before they died.

SEPTEMBER 2003

Alice sat at her desk in their bedroom distracted by the sounds of John racing through each of the rooms on the first floor. She needed to finish her peer review of a paper submitted to the Journal of Cognitive Psychology before her flight, and she’d just read the same sentence three times without comprehending it. It was 7:30 according to their alarm clock, which she guessed was about ten minutes fast. She knew from the approximate time and the escalating volume of his racing that he was trying to leave, but he’d forgotten something and couldn’t find it. She tapped her red pen on her bottom lip as she watched the digital numbers on the clock and listened for what she knew was coming.

“Ali?”

She tossed her pen onto the desk and sighed. Downstairs, she found him in the living room on his knees, feeling under the couch cushions.

“Keys?” she asked.

“Glasses. Please don’t lecture me, I’m late.”

She followed his frantic glance to the fireplace mantel, where the antique Waltham clock, valued for its precision, declared 8:00. He should have known better than to trust it. The clocks in their home rarely knew the real time of day. Alice had been duped too often in the past by their seemingly honest faces and had learned long ago to rely on her watch. Sure enough, she lapsed back in time as she entered the kitchen, where the microwave insisted that it was only 6:52.

She looked across the smooth, uncluttered surface of the granite countertop, and there they were, next to the mushroom bowl heaping with unopened mail. Not under something, not behind something, not obstructed in any way from plain view. How could he, someone so smart, a scientist, not see what was right in front of him?

Of course, many of her own things had taken to hiding in mischievous little places as well. But she didn’t admit this to him, and she didn’t involve him in the hunt. Just the other day, John blissfully unaware, she’d spent a crazed morning looking first all over the house and then in her office for her BlackBerry charger. Stumped, she’d surrendered, gone to the store, and bought a new one, only to discover the old one later that night plugged in the socket next to her side of the bed, where she should have known to look. She could probably chalk it all up for both of them to excessive multitasking and being way too busy. And to getting older.

He stood in the doorway, looking at the glasses in her hand but not at her.

“Next time, try pretending you’re a woman while you look,” said Alice, smiling.

“I’ll wear one of your skirts. Ali, please, I’m really late.”

“The microwave says you have tons of time,” she said, handing them to him.

“Thanks.”

He grabbed them like a relay runner taking a baton in a race and headed for the front door.

“Will you be here when I get home on Saturday?” she asked his back as she followed him down the hallway.

“I don’t know, I’ve got a huge day in lab on Saturday.”

He collected his briefcase, phone, and keys from the hall table.

“Have a good trip, give Lydia a hug and kiss for me. And try not to battle with her,” said John.

She caught their reflection in the hallway mirror—a distinguished-looking, tall man with white-flecked brown hair and glasses; a petite, curly-haired woman, her arms crossed over her chest, each readying to leap into that same, bottomless argument. She gritted her teeth and swallowed, choosing not to jump.

“We haven’t seen each other in a while. Please try to be home?” she asked.

“I know, I’ll try.”

He kissed her, and although desperate to leave, he lingered in that kiss for an almost imperceptible moment. If she didn’t know him better, she might’ve romanticized his kiss. She might’ve stood there, hopeful, thinking it said, I love you, I’ll miss you. But as she watched him hustle down the street alone, she felt pretty certain he’d just told her, I love you, but please don’t be pissed when I’m not home on Saturday.

They used to walk together over to Harvard Yard every morning. Of the many things she loved about working within a mile from home and at the same school, their shared commute was the thing she loved most. They always stopped at Jerri’s—a black coffee for him, a tea with lemon for her, iced or hot, depending on the season—and continued on to Harvard Yard, chatting about their research and classes, issues in their respective departments, their children, or plans for that evening. When they were first married, they even held hands. She savored the relaxed intimacy of these morning walks with him, before the daily demands of their jobs and ambitions rendered them each stressed and exhausted.

But for some time now, they’d been walking over to Harvard separately. Alice had been living out of her suitcase all summer, attending psychology conferences in Rome, New Orleans, and Miami, and serving on an exam committee for a thesis defense at Princeton. Back in the spring, John’s cell cultures had needed some sort of rinsing attention at an obscene hour each morning, but he didn’t trust any of his students to show up consistently. So he did. She couldn’t remember the reasons that predated spring, but she knew that each time they’d seemed reasonable and only temporary.

She returned to the paper at her desk, still distracted, now by a craving for that fight she hadn’t had with John about their younger daughter, Lydia. Would it kill him to stand behind her for once? She gave the rest of the paper a cursory effort, not her typical standard of excellence, but it would have to do, given her fragmented state of mind and lack of time. Her comments and suggestions for revision finished, she packaged and sealed the envelope, guiltily aware that she might’ve missed an error in the study’s design or interpretation, cursing John for compromising the integrity of her work.

She repacked her suitcase, not even emptied yet from her last trip. She looked forward to traveling less in the coming months. There were only a handful of invited lectures penciled in her fall semester calendar, and she’d scheduled most of those on Fridays, a day she didn’t teach. Like tomorrow. Tomorrow she would be the guest speaker to kick off Stanford’s cognitive psychology fall colloquium series. And afterward, she’d see Lydia. She’d try not to battle with her, but she wasn’t making any promises.

ALICE FOUND HER WAY EASILY to Stanford’s Cordura Hall on the corner of Campus Drive West and Panama Drive. Its white stucco exterior, terra-cotta roof, and lush landscaping looked to her East Coast eyes more like a Caribbean beach resort than an academic building. She arrived quite early but ventured inside anyway, figuring she could use the extra time to sit in the quiet auditorium and look over her talk.

Much to her surprise, she walked into an already packed room. A zealous crowd surrounded and circled a buffet table, aggressively diving in for food like seagulls at a city beach. Before she could sneak in unnoticed, she noticed Josh, a former Harvard classmate and respected egomaniac, standing in her path, his legs planted firmly and a little too wide, as if he was ready to dive at her.

“All this, for me?” asked Alice, smiling playfully.

“What, we eat like this every day. It’s for one of our developmental psychologists, he was tenured yesterday. So how’s Harvard treating you?”

“Good.”

“I can’t believe you’re still there after all these years. You ever get too bored over there, you should consider coming here.”

“I’ll let you know. How are things with you?”

“Fantastic. You should come by my office after the talk, see our latest modeling data. It’ll really knock your socks off.”

“Sorry, I can’t, I have to catch a flight to L.A. right after this,” she said, grateful to have a ready excuse.

“Oh, too bad. Last time I saw you I think was last year at the psychonomic conference. I unfortunately missed your presentation.”

“Well, you’ll get to hear a good portion of it today.”

“Recycling your talks these days, huh?”

Before she could answer, Gordon Miller, head of the department and her new superhero, swooped in and saved her by asking Josh to help pass out the champagne. As at Harvard, a champagne toast was a tradition in the psychology department at Stanford for all faculty who reached the coveted career milestone of tenure. There weren’t many trumpets that heralded the advancement from point to point in the career of a professor, but tenure was a big one, loud and clear.

When everyone was holding a cup, Gordon stood at the podium and tapped the microphone. “Can I have everyone’s attention for a moment?”

Josh’s excessively loud, punctuated laugh reverberated alone through the auditorium just before Gordon continued.

“Today, we congratulate Mark on receiving tenure. I’m sure he’s thrilled to have this particular accomplishment behind him. Here’s to the many exciting accomplishments still ahead. To Mark!”

“To Mark!”

Alice tapped her cup with her neighbors’, and everyone quickly resumed the business of drinking, eating, and discussing. When all of the food had been claimed from the serving trays and the last drops of champagne emptied from the last bottle, Gordon took the floor once again.

“If everyone would take a seat, we can begin today’s talk.”

He waited a few moments for the crowd of about seventy-five to settle and quiet down.

“Today, I have the honor of introducing you to our first colloquium speaker of the year. Dr. Alice Howland is the eminent William James Professor of Psychology at Harvard University. Over the last twenty-five years, her distinguished career has produced many of the flagship touchstones in psycholinguistics. She pioneered and continues to lead an interdisciplinary and integrated approach to the study of the mechanisms of language. We are privileged to have her here today to talk to us about the conceptual and neural organization of language.”

Alice switched places with Gordon and looked out at her audience looking at her. As she waited for the applause to subside, she thought of the statistic that said people feared public speaking more than they feared death. She loved it. She enjoyed all of the concatenated moments of presenting in front of a listening audience—teaching, performing, telling a story, teeing up a heated debate. She also loved the adrenaline rush. The bigger the stakes, the more sophisticated or hostile the audience, the more the whole experience thrilled her. John was an excellent teacher, but public speaking often pained and terrified him, and he marveled at Alice’s verve for it. He probably didn’t prefer death, but spiders and snakes, sure.

“Thank you, Gordon. Today, I’m going to talk about some of the mental processes that underlie the acquisition, organization, and use of language.”

Alice had given the guts of this particular talk innumerable times, but she wouldn’t call it recycling. The crux of the talk did focus on the main tenets of linguistics, many of which she’d discovered, and she’d been using a number of the same slides for years. But she felt proud, and not ashamed or lazy, that this part of her talk, these discoveries of hers, continued to hold true, withstanding the test of time. Her contributions mattered and propelled future discovery. Plus, she certainly included those future discoveries.

She talked without needing to look down at her notes, relaxed and animated, the words effortless. Then, about forty minutes into the fifty-minute presentation, she became suddenly stuck.

“The data reveal that irregular verbs require access to the mental…”

She simply couldn’t find the word. She had a loose sense for what she wanted to say, but the word itself eluded her. Gone. She didn’t know the first letter or what the word sounded like or how many syllables it had. It wasn’t on the tip of her tongue.

Maybe it was the champagne. She normally didn’t drink any alcohol before speaking. Even if she knew the talk cold, even in the most casual setting, she always wanted to be as mentally sharp as possible, especially for the question-and-answer session at the end, which could be confrontational and full of rich, unscripted debate. But she hadn’t wanted to offend anyone, and she’d drunk a little more than she probably should have when she became trapped again in passive-aggressive conversation with Josh.

Maybe it was jet lag. As her mind scoured its corners for the word and a rational reason for why she’d lost it, her heart pounded and her face grew hot. She’d never lost a word in front of an audience before. But she’d never panicked in front of an audience either, and she’d stood before many far larger and more intimidating than this. She told herself to breathe, forget about it, and move on.

She replaced the still blocked word with a vague and inappropriate “thing,” abandoned whatever point she’d been in the middle of making, and continued on to the next slide. The pause had seemed like an obvious and awkward eternity to her, but as she checked the faces in the audience to see if anyone had noticed her mental hiccup, no one appeared alarmed, embarrassed, or ruffled in any way. Then, she saw Josh whispering to the woman next to him, his eyebrows furrowed and a slight smile on his face.

She was on the plane, descending into LAX, when it finally came to her.

Lexicon.

LYDIA HAD BEEN LIVING IN Los Angeles for three years now. If she’d gone to college right after high school, she would’ve graduated this past spring. Alice would’ve been so proud. Lydia was probably smarter than both of her older siblings, and they had gone to college. And law school. And medical school.

Instead of college, Lydia first went to Europe. Alice had hoped she’d come home with a clearer sense of what she wanted to study and what kind of school she wanted to go to. Instead, upon her return, she’d told her parents that she’d done a little acting while in Dublin and had fallen in love. She was moving to Los Angeles immediately.

Alice nearly lost her mind. Much to her maddening frustration, she recognized her own contribution to this problem. Because Lydia was the youngest of three, the daughter of parents who worked a lot and traveled regularly, and had always been a good student, Alice and John had ignored her to a large extent. They’d granted her a lot of room to run in her world, free to think for herself and free from the kind of micromanagement placed on a lot of children her age. Her parents’ professional lives served as shining examples of what could be gained from setting lofty and individually unique goals and pursuing them with passion and hard work. Lydia understood her mother’s advice about the importance of getting a college education, but she had the confidence and audacity to reject it.

Plus, she didn’t stand entirely alone. The most explosive fight Alice had ever had with John had followed his two cents on the subject: I think it’s wonderful, she can always go to college later, if she decides she even wants to.

Alice checked her BlackBerry for the address, rang the doorbell to apartment number seven, and waited. She was just about to press it again when Lydia opened the door.

“Mom, you’re early,” said Lydia.

Alice checked her watch.

“I’m right on time.”

“You said your flight was coming in at eight.”

“I said five.”

“I have eight o’clock written down in my book.”

“Lydia, it’s five forty-five, I’m here.”

Lydia looked indecisive and panicky, like a squirrel caught facing an oncoming car in the road.

“Sorry, come in.”

They each hesitated before they hugged, as if they were about to practice a newly learned dance and weren’t quite confident of the first step or who should lead. Or it was an old dance, but they hadn’t performed it together in so long that each felt unsure of the choreography.

Alice could feel the contours of Lydia’s spine and ribs through her shirt. She looked too skinny, a good ten pounds lighter than Alice remembered. She hoped it was more a result of being busy than of conscious dieting. Blond and five foot six, three inches taller than Alice, Lydia stood out among the predominance of short Italian and Asian women in Cambridge, but in Los Angeles, the waiting rooms at every audition were apparently full of women who looked just like her.

“I made reservations for nine. Wait here, I’ll be right back.”

Craning her neck, Alice inspected the kitchen and living room from the hallway. The furnishings, most likely yard sale finds and parent hand-me-downs, looked rather hip together—an orange sectional couch, retro-inspired coffee table, Brady Bunch–style kitchen table and chairs. The white walls were bare except for a poster of Marlon Brando taped above the couch. The air smelled strongly of Windex, as if Lydia had taken last-second measures to clean the place before Alice’s arrival.

In fact, it was a little too clean. No DVDs or CDs lying around, no books or magazines thrown on the coffee table, no pictures on the refrigerator, no hint of Lydia’s interests or aesthetic anywhere. Anyone could be living here. Then, Alice noticed the pile of men’s shoes on the floor to the left of the door behind her.

“Tell me about your roommates,” she said as Lydia returned from her room, cell phone in hand.

“They’re at work.”

“What kind of work?”

“One’s bartending and the other delivers food.”

“I thought they were both actors.”

“They are.”

“I see. What are their names again?”

“Doug and Malcolm.”

It flashed only for a moment, but Alice saw it and Lydia saw her see it. Lydia’s face flushed when she said Malcolm’s name, and her eyes darted nervously away from her mother’s.

“Why don’t we get going? They said they can take us early,” said Lydia.

“Okay, I just need to use the bathroom first.”

As Alice washed her hands, she looked over the products sitting on the table next to the sink—Neutrogena facial cleanser and moisturizer, Tom’s of Maine mint toothpaste, men’s deodorant, a box of Playtex tampons. She thought for a moment. She hadn’t had her period all summer. Did she have it in May? She’d be turning fifty next month, so she wasn’t alarmed. She hadn’t yet experienced any hot flashes or night sweats, but not all menopausal women did. That would be just fine with her.

As she dried her hands, she noticed the box of Trojan condoms behind Lydia’s hairstyling products. She was going to have to find out more about these roommates. Malcolm, in particular.

They sat at a table outside on the patio at Ivy, a trendy restaurant in downtown Los Angeles, and ordered two drinks, an espresso martini for Lydia and a merlot for Alice.

“So how’s Dad’s Science paper coming?” asked Lydia.

She must’ve talked recently with her father. Alice hadn’t heard from her since a phone call on Mother’s Day.

“It’s done. He’s very proud of it.”

“How’s Anna and Tom?”

“Good, busy, working hard. So how did you meet Doug and Malcolm?”

“They came into Starbucks one night while I was working.”

The waiter appeared, and each of them ordered dinner and another drink. Alice hoped the alcohol would dilute the tension between them, which felt heavy and thick and just beneath the tracing-paper-thin conversation.

“So how did you meet Doug and Malcolm?” she asked.

“I just told you. Why don’t you ever listen to anything I say? They came into Starbucks one night talking about looking for a roommate while I was working.”

“I thought you were waitressing at a restaurant.”

“I am. I work at Starbucks during the week and waitress on Saturday nights.”

“Doesn’t sound like that leaves a lot of time for acting.”

“I’m not cast in anything right now, but I’m taking workshop classes, and I’m auditioning a lot.”

“What kind of classes?”

“Meisner technique.”

“And what’ve you been auditioning for?”

“Television and print.”

Alice swirled her wine, drank the last, big gulp, and licked her lips. “Lydia, what exactly is your plan here?”

“I’m not planning on stopping, if that’s what you’re asking.”

The drinks were taking effect, but not in the direction Alice had hoped for. Instead, they served as the fuel that burned that little piece of tracing paper, leaving the tension between them fully exposed and at the helm of a dangerously familiar conversation.

“You can’t live like this forever. Are you still going to work at Starbucks when you’re thirty?”

“That’s eight years away! Do you know what you’ll be doing in eight years?”

“Yes, I do. At some point, you need to be responsible, you need to be able to afford things like health insurance, a mortgage, savings for retirement—”