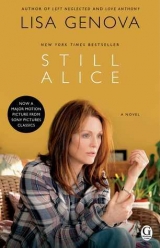

Текст книги "Still Alice"

Автор книги: Lisa Genova

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

ALICE STOOD IN THEIR BEDROOM, naked but for a pair of ankle socks and her Safe Return bracelet, wrestling and growling at an article of clothing stretched around her head. Like a Martha Graham dance, her battle against the fabric shrouding her head looked like a physical and poetic expression of anguish. She let out a long scream.

“What’s happening?” asked John, running in.

She looked at him with one panicked eye through a round hole in the twisted garment.

“I can’t do this! I can’t figure out how to put on this fucking sports bra. I can’t remember how to put on a bra, John! I can’t put on my own bra!”

He went to her and examined her head.

“That’s not a bra, Ali, it’s a pair of underwear.”

She burst into laughter.

“It’s not funny,” said John.

She laughed harder.

“Stop it, it’s not funny. Look, if you want to go running, you have to hurry up and get dressed. I don’t have a lot of time.”

He left the room, unable to watch her standing there, naked with her underwear on her head, laughing at her own absurd madness.

ALICE KNEW THAT THE YOUNG woman sitting across from her was her daughter, but she had a disturbing lack of confidence in this knowledge. She knew that she had a daughter named Lydia, but when she looked at the young woman sitting across from her, knowing that she was her daughter Lydia was more academic knowledge than implicit understanding, a fact she agreed to, information she’d been given and accepted as true.

She looked at Tom and Anna, also sitting at the table, and she could automatically connect them with the memories she had of her oldest child and her son. She could picture Anna in her wedding gown, in her law school, college, and high school graduation gowns, and in the Snow White nightgown she’d insisted on wearing every day when she was three. She could remember Tom in his cap and gown, in a cast when he broke his leg skiing, in braces, in his Little League uniform, and in her arms when he was an infant.

She could see Lydia’s history as well, but somehow this woman sitting across from her wasn’t inextricably connected to her memories of her youngest child. This made her uneasy and painfully aware that she was declining, her past becoming unhinged from her present. And how strange that she had no problem identifying the man next to Anna as Anna’s husband, Charlie, who had entered their lives only a couple of years ago. She pictured her Alzheimer’s as a demon in her head, tearing a reckless and illogical path of destruction, ripping apart the wiring from “Lydia now” to “Lydia then,” leaving all the “Charlie” connections unscathed.

The restaurant was crowded and noisy. Voices from other tables competed for Alice’s attention, and the music in the background moved in and out of the foreground. Anna’s and Lydia’s voices sounded the same to her. Everyone used too many pronouns. She struggled to locate who was talking at her table and to follow what was being said.

“Honey, you okay?” asked Charlie.

“The smells,” said Anna.

“You want to go outside for a minute?” asked Charlie.

“I’ll go with her,” said Alice.

Alice’s back tensed as soon as they left the cozy warmth of the restaurant. They’d both forgotten to bring their coats. Anna grabbed Alice’s hand and led her away from a circle of young smokers hovering near the door.

“Ahh, fresh air,” said Anna, taking a luxurious breath in and out through her nose.

“And quiet,” said Alice.

“How are you feeling, Mom?”

“I’m okay,” said Alice.

Anna rubbed the back of Alice’s hand, the hand she was still holding.

“I’ve been better,” she admitted.

“Same here,” said Anna. “Were you sick like this when you were pregnant with me?”

“Uh-huh.”

“How did you do it?”

“You just keep going. It’ll stop soon.”

“And before you know it, the babies will be here.”

“I can’t wait.”

“Me, too,” Anna said. But her voice didn’t carry the same exuberance Alice’s did. Her eyes suddenly filled with tears.

“Mom, I feel sick all the time, and I’m exhausted, and every time I forget something I think I’m becoming symptomatic.”

“Oh, sweetie, you’re not, you’re just tired.”

“I know, I know. It’s just when I think about you not teaching anymore and everything you’re losing—”

“Don’t. This should be an exciting time for you. Please, just think about what we’re gaining.”

Alice squeezed the hand she held and placed her other one gently on Anna’s stomach. Anna smiled, but the tears still spilled out of her overwhelmed eyes.

“I just don’t know how I’m going to handle it all. My job and two babies and—”

“And Charlie. Don’t forget about you and Charlie. Keep what you have with him. Keep everything in balance—you and Charlie, your career, your kids, everything you love. Don’t take any of the things you love in your life for granted, and you’ll do it all. Charlie will help you.”

“He better,” Anna threatened.

Alice laughed. Anna wiped her eyes several times with the heels of her hands and blew a long, Lamaze-like breath out through her mouth.

“Thanks, Mom. I feel better.”

“Good.”

Back inside the restaurant, they settled into their seats and ate dinner. The young woman across from Alice, her youngest child, Lydia, clanged her empty wineglass with her knife.

“Mom, we’d like to give you your big gift now.”

Lydia presented her with a small, rectangular package wrapped in gold paper. It must have been big in significance. Alice untaped the paper. Inside were three DVDs—The Howland Kids, Alice and John, and Alice Howland.

“It’s a video memoir for you. The Howland Kids is a collection of interviews of Anna, Tom, and me. I shot them this summer. It’s our memories of you and our childhoods and growing up. The one with Dad is of his memories of meeting you and dating and your wedding and vacations and lots of other stuff. There are a couple of really great stories in that one that none of us kids knew about. The third one I haven’t made yet. It’s an interview of you, of your stories, if you want to do it.”

“I absolutely want to do it. I love it. Thank you, I can’t wait to watch them.”

The waitress brought them coffee, tea, and chocolate cake with a candle in it. They all sang “Happy Birthday.” Alice blew out the candle and made a wish.

NOVEMBER 2004

The movies that John had bought over the summer now fell into the same unfortunate category as the abandoned books they’d replaced. She could no longer follow the thread of the plot or remember the significance of the characters if they weren’t in every scene. She could appreciate small moments but retained only a general sense of the film after the credits rolled. That movie was funny. If John or Anna watched with her, they would many times roar with laughter or jump with alarm or cringe with disgust, reacting in an obvious, visceral way to something that happened, and she wouldn’t understand why. She would join in, faking it, trying to protect them from how lost she was. Watching movies made her keenly aware of how lost she was.

The DVDs Lydia had made came at just the right time. Each story told by John and the kids ran only a few minutes long, so she could absorb each one, and she didn’t have to actively hold the information in any particular story to understand or enjoy the others. She watched them over and over. She didn’t remember everything they talked about, but this felt completely normal, for each of her children and John didn’t remember all of the details either. And when Lydia asked them all to recount the same event, each remembered it somewhat differently, omitting some parts, exaggerating others, emphasizing their own individual perspectives. Even biographies not saturated with disease were vulnerable to holes and distortions.

She could only stomach watching the Alice Howland video once. She used to be so eloquent, so comfortable talking in front of any audience. Now, she overused the word thingy and repeated herself an embarrassing number of times. But she felt grateful to have it, her memories, reflections, and advice recorded and pinned down, safe from the molecular mayhem of Alzheimer’s disease. Her grandchildren would watch it someday and say, “That’s Grandma when she could still talk and remember things.”

She had just finished watching Alice and John. She remained on the couch with a blanket on her lap after the television screen faded to black and listened. The quiet pleased her. She breathed and thought of nothing for several minutes but the sound of the ticking clock on the fireplace mantel. Then, suddenly, the ticking took on meaning, and her eyes popped open.

She looked at the hands. Ten minutes until ten o’clock. Oh my god, what am I still doing here? She threw the blanket onto the floor, crammed her feet into her shoes, ran into the study, and clicked her laptop bag shut. Where’s my blue bag? Not on the chair, not on the desk, not in the desk drawers, not in the laptop bag. She jogged up to her bedroom. Not on her bed, not on the night table, not on the dresser, not in the closet, not on the desk. She was standing in the hallway, retracing her whereabouts in her boggled mind, when she saw it, hanging on the bathroom doorknob.

She unzipped it. Cell phone, BlackBerry, no keys. She always put them in there. Well, that wasn’t entirely true. She always meant to put them in there. Sometimes, she put them in her desk drawer, the silverware drawer, her underwear drawer, her jewelry box, the mailbox, and any number of pockets. Sometimes, she simply left them in the keyhole. She hated to think of how many minutes each day she spent looking for her own misplaced things.

She bolted back downstairs to the living room. No keys, but she found her coat on the wing chair. She put it on and shoved her hands in the pockets. Keys!

She raced to the front hallway, but then stopped before she could reach the door. It was the strangest thing. There was a large hole in the floor just in front of the door. It spanned the width of the hallway and was about eight or nine feet in length, with nothing but the dark basement below it. It was impassable. The front hall floorboards were warped and creaky, and she and John had talked recently about replacing them. Had John hired a contractor? Had someone been here today? She couldn’t remember. Whatever the reason, there was no using the front door until the hole was fixed.

On her way to the back door, the phone rang.

“Hi, Mom. I’ll be over around seven, and I’ll bring dinner.”

“Okay,” said Alice, a slight rise in her tone.

“It’s Anna.”

“I know.”

“Dad’s in New York until tomorrow, remember? I’m sleeping over tonight. I can’t get out of work before six thirty, though, so wait for me to eat. Maybe you should write this down on the whiteboard on the fridge.”

She looked over at the whiteboard.

DO NOT GO RUNNING WITHOUT ME.

Provoked, she wanted to scream into the phone that she didn’t need a babysitter, and she could manage just fine alone in her own house. She breathed instead.

“Okay, see you later.”

She hung up the phone and congratulated herself on still having editorial control over her raw emotions. Someday soon, she wouldn’t. She would enjoy seeing Anna, and it would be good not to be alone.

She had her coat on and her laptop and baby blue bag slung over her shoulder. She looked out the kitchen window. Windy, damp, gray. Morning, maybe? She didn’t feel like going outside, and she didn’t feel like sitting in her office. She felt bored, ignored, and alienated in her office. She felt ridiculous there. She didn’t belong there anymore.

She removed her bags and coat and headed for the study, but a sudden thud and clink made her backtrack to the front hallway. The mail had just been delivered through the slot in the door, and it lay on top of the hole, somehow hovering there. It had to be balancing on an underlying beam or floorboard that she couldn’t see. Floating mail. My brain is fried! She retreated into the study and tried to forget about the gravity-defying hole in the front hallway. It was surprisingly difficult.

SHE SAT IN HER STUDY, hugging her knees, staring out the window at the darkened day, waiting for Anna to come over with dinner, waiting for John to return from New York so she could go for a run. She was sitting and waiting. She was sitting and waiting to get worse. She was sick of just sitting and waiting.

She was the only person she knew with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease at Harvard. She was the only person she knew anywhere with early-onset Alzheimer’s. Surely, she wasn’t the only one anywhere. She needed to find her new colleagues. She needed to inhabit this new world she found herself in, this world of dementia.

She typed the words “early-onset Alzheimer’s disease” into Google. It pulled up a lot of facts and statistics.

There are an estimated five hundred thousand people in the United States with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

Early-onset is defined as Alzheimer’s under the age of sixty-five.

Symptoms can develop in the thirties and forties.

It pulled up sites with lists of symptoms, genetic risk factors, causes, and treatments. It pulled up articles about research and drug discovery. She’d seen all this before.

She added the word “support” to her Google search and hit the return key.

She found forums, links, resources, message boards, and chat rooms. For caregivers. Caregiver help topics included visiting the nursing facility, questions about medications, stress relief, dealing with delusions, dealing with night wandering, coping with denial and depression. Caregivers posted questions and answers, commiserating about and troubleshooting issues regarding their eighty-one-year-old mothers, their seventy-four-year-old husbands, and their eighty-five-year-old grandmothers with Alzheimer’s disease.

What about support for the people with Alzheimer’s disease? Where are the other fifty-one-year-olds with dementia? Where are the other people who were in the middle of their careers when this diagnosis ripped their lives right out from under them? She didn’t deny that getting Alzheimer’s was tragic at any age. She didn’t deny that caregivers needed support. She didn’t deny that they suffered. She knew that John suffered. But what about me?

She remembered the business card of the social worker at Mass General Hospital. She found it and dialed the number.

“Denise Daddario.”

“Hi, Denise, this is Alice Howland. I’m a patient of Dr. Davis, and he gave me your card. I’m fifty-one, and I was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s almost a year ago. I was wondering, does MGH run any sort of support group for people with Alzheimer’s?”

“No, unfortunately we don’t. We have a support group, but it’s only for caregivers. Most of our patients with Alzheimer’s wouldn’t be capable of participating in that kind of forum.”

“But some would.”

“Yes, but I’m afraid we don’t have the numbers to justify the resources it would take to get that kind of group up and running.”

“What kinds of resources?”

“Well, with our caregivers’ support group, about twelve to fifteen people meet every week for a couple of hours. We have a room reserved, coffee, pastries, a couple of people on staff who act as facilitators, and a guest speaker once a month.”

“What about just an empty room where people with early-onset dementia can meet and talk about what we’re experiencing?”

I can bring the coffee and jelly donuts, for god’s sake.

“We’d need someone on staff at the hospital to oversee it, and we unfortunately don’t have anyone available right now.”

How about one of the two facilitators from your caregivers’ support group?

“Can you give me the contact information for the patients you know of with early-onset dementia so I can try to organize something on my own?”

“I’m afraid I can’t give out that information. Would you like to make an appointment to come in and talk with me? I have an opening at ten in the morning on Friday, December seventeenth.”

“No thanks.”

A NOISE AT THE FRONT door woke her from her nap on the couch. The house was cold and dark. The front door squeaked as it opened.

“Sorry I’m late!”

Alice rose and walked to the hallway. Anna stood there with a big brown paper bag in one hand and a jumbled pile of mail in the other. She was standing on the hole!

“Mom, all the lights are off in here. Were you sleeping? You shouldn’t be napping this late in the day, you’ll never sleep tonight.”

Alice walked over to her and crouched down. She put her hand on the hole. Only it wasn’t empty space she felt. She ran her fingers over the looped wool of a black rug. Her black hallway rug. It’d been there for years. She smacked it with her open hand so hard the sound she made echoed.

“Mom, what are you doing?”

Her hand stung, she was too tired to endure the humiliating answer to Anna’s question, and an overpowering peanut smell coming from the bag disgusted her.

“Leave me alone!”

“Mom, it’s okay. Let’s go in the kitchen and have dinner.”

Anna put the mail down and reached for her mother’s hand, the hand that stung. Alice flung it away from her and screamed.

“Leave me alone! Get out of my house! I hate you! I don’t want you here!”

Her words hit Anna’s face harder than if she’d slapped her. Through the tears that streamed down it, Anna’s expression clenched into calm resolve.

“I brought dinner, I’m starving, and I’m staying. I’m going into the kitchen to eat, and then I’m going to bed.”

Alice stood in the hallway alone, fury and fight raging madly through her veins. She opened the door and began pulling at the rug. She yanked with all her strength and was knocked down. She got up and pulled and twisted and wrestled it until it was entirely outside. Then, she kicked and screamed wildly at it until it limped down the front steps and lay lifeless on the sidewalk.

Alice, answer the following questions:

1. What month is it?

2. Where do you live?

3. Where is your office?

4. When is Anna’s birthday?

5. How many children do you have?

If you have trouble answering any of these, go to the file named “Butterfly” on your computer and follow the instructions there immediately.

November

Cambridge

Harvard

September

Three

DECEMBER 2004

Dan’s thesis numbered 142 pages, not including references. Alice hadn’t read anything that long in a long time. She sat on the couch with Dan’s words in her lap, a red pen balanced on her right ear, and a pink highlighter in her right hand. She used the red pen for editing and the pink highlighter for keeping track of what she’d already read. She highlighted anything that struck her as important, so when she needed to backtrack, she could limit her rereading to the colored words.

She became hopelessly stalled on page twenty-six, which was saturated in pink. Her brain felt overwhelmed and begged her for rest. She imagined the pink words on the page transforming into sticky pink cotton candy in her head. The more she read, the more she needed to highlight to understand and remember what she was reading. The more she highlighted, the more her head became packed with pink, woolly sugar, clogging and muffling the circuits in her brain that were needed to understand and remember what she was reading. By page twenty-six, she understood nothing.

Beep, beep.

She tossed Dan’s thesis onto the coffee table and went to the computer in the study. She found one new email in her inbox, from Denise Daddario.

Dear Alice,

I’ve shared your idea for an early-stage dementia support group with the other early-onsetters here in our unit and with the folks at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. I’ve heard back from three people who are local and very interested in this idea. They’ve given me permission to give you their names and contact information (see attachment).

You might also want to contact the Mass Alzheimer’s Association. They may know of others who’d want to meet with you.

Keep me posted with how it goes, and let me know if I can provide you with any other information or advice. I’m sorry we couldn’t formally do more for you here.

Good luck!

Denise Daddario

She opened the attachment.

Mary Johnson, age fifty-seven, Frontotemporal lobe dementia

Cathy Roberts, age forty-eight, Early-onset Alzheimer’s disease

Dan Sullivan, age fifty-three, Early-onset Alzheimer’s disease

There they were, her new colleagues. She read their names over and over. Mary, Cathy, and Dan. Mary, Cathy, and Dan. She began to feel the kind of wondrous excitement mixed with barely suppressed dread she’d experienced in the weeks before her first days of kindergarten, college, and graduate school. What did they look like? Were they still working? How long had they been living with their diagnoses? Were their symptoms the same, milder, or worse? Were they anything like her? What if I’m much further along than they are?

Dear Mary, Cathy, and Dan,

My name is Alice Howland. I am fifty-one years old and was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease last year. I was a psychology professor at Harvard University for twenty-five years but essentially failed out of my position due to my symptoms this September.

Now I’m home and feeling really alone in this. I called Denise Daddario at MGH for information on an early-stage dementia support group. They only have one for caregivers, nothing for us. But she gave me your names.

I’d like to invite you all to my house for tea, coffee, and conversation this Sunday, December 5, at 2:00. Your caregivers are welcome to come and stay if you’d like. Attached are my address and directions.

I’m looking forward to meeting you,

Alice

Mary, Cathy, and Dan. Mary, Cathy, and Dan. Dan. Dan’s thesis. He’s waiting for my edits. She returned to the living room couch and opened Dan’s thesis to page twenty-six. The pink rushed into her head. Her head ached. She wondered if anyone had replied yet. She abandoned Dan’s thingy before she even finished the thought.

She clicked on her inbox. Nothing new.

Beep, beep.

She picked up the phone.

“Hello?”

Dial tone. She’d hoped it was Mary, Cathy, or Dan. Dan. Dan’s thesis.

Back on the couch, she looked poised and active with the highlighter in her hand, but her eyes weren’t focused on the letters on the page. Instead, she daydreamed.

Could Mary, Cathy, and Dan still read twenty-six pages and understand and remember all that they read? What if I’m the only one who thinks the hallway rug could be a hole? What if she was the only one declining? She could feel herself declining. She could feel herself slipping into that demented hole. Alone.

“I’m alone, I’m alone, I’m alone,” she moaned, sinking further into the truth of her lonely hole each time she heard her own voice say the words.

Beep, beep.

The doorbell snapped her out of it. Were they here? Had she invited them over today?

“Just a minute!”

She rubbed her eyes with her sleeves, combed her fingers through her matted hair as she walked, took a deep breath, and opened the door. There was no one there.

Auditory and visual hallucinations were realities for about half of people with Alzheimer’s disease, but so far she hadn’t experienced any. Or maybe she had. When she was alone, there wasn’t any clear way of knowing whether what she experienced was reality or her reality with Alzheimer’s. It wasn’t as if her disorientations, confabulations, delusions, and all other demented thingies were highlighted in fluorescent pink, unmistakably distinguishable from what was normal, actual, and correct. From her perspective, she simply couldn’t tell the difference. The rug was a hole. That noise was the doorbell.

She checked her inbox again. One new email.

Hi Mom,

How are you? Did you go to the lunch seminar yesterday? Did you run? My class was great, as usual. I had another audition today for a bank commercial. We’ll see. How’s Dad doing? Is he home this week? I know last month was hard. Hang in there. I’ll be home soon!

Love,

Lydia

Beep, beep.

She picked up the phone.

“Hello?”

Dial tone. She opened the top file cabinet drawer, dropped the phone inside, heard it hit the metal bottom beneath hundreds of hanging reprints, and slid the drawer shut. Wait, maybe it’s my cell phone.

“Cell phone, cell phone, cell phone,” she chanted aloud as she roamed the house, trying to keep the goal of her search present.

She checked everywhere but couldn’t find it. Then she figured out that she needed to be looking for her baby blue bag. She changed the chant.

“Blue bag, blue bag, blue bag.”

She found it on the kitchen counter, her cell phone inside, but off. Maybe the noise was someone’s car alarm locking or unlocking outside. She resumed her position on the couch and opened Dan’s thesis to page twenty-six.

“Hello?” asked a man’s voice.

Alice looked up, eyes wide, and listened, as if she’d just been summoned by a ghost.

“Alice?” asked the disembodied voice.

“Yes?”

“Alice, are you ready to go?”

John appeared in the threshold of the living room looking expectant. She was relieved but needed more information.

“Let’s go. We’re meeting Bob and Sarah for dinner, and we’re already a little late.”

Dinner. She just realized she was starving. She didn’t remember eating any food today. Maybe that was why she couldn’t read Dan’s thesis. Maybe she just needed some food. But the thought of dinner and conversation in a loud restaurant drained her further.

“I don’t want to go to dinner. I’m having a hard day.”

“I had a hard day, too. Let’s go have a nice dinner together.”

“You go. I just want to be home.”

“Come on, it’ll be fun. We didn’t go to Eric’s party. It’ll be good for you to get out, and I know they’d like to see you.”

No, they wouldn’t. They’ll be relieved that I’m not there. I’m a cotton candy pink elephant in the room. I make everyone uncomfortable. I turn dinner into a crazy circus act, everyone juggling their nervous pity and forced smiles with their cocktail glasses, forks, and knives.

“I don’t want to go. Tell them I’m sorry, but I wasn’t feeling up to it.”

Beep, beep.

She saw John hear the noise, too, and she followed him into the kitchen. He popped open the microwave oven door and pulled out a mug.

“This is freezing cold. Do you want me to reheat it?”

She must’ve made tea that morning, and she’d forgotten to drink it. Then, she must’ve put it in the microwave to reheat it and left it there.

“No, thanks.”

“All right, Bob and Sarah are probably already there waiting. Are you sure you don’t want to come?”

“I’m sure.”

“I won’t stay long.”

He kissed her and then left without her. She stood in the kitchen where he left her for a long time, holding the mug of cold tea in her hands.

SHE WAS ON HER WAY to bed, and John still hadn’t returned from dinner. The blue computer light glowing in the study caught her attention before she turned to go upstairs. She went in and checked her inbox, more out of habit than out of sincere curiosity.

There they were.

Dear Alice,

My name is Mary Johnson. I’m 57 and was diagnosed with FTD five years ago. I live on the North Shore, so not too far from you. This is such a wonderful idea. I’d love to come. My husband, Barry, will drive me. I’m not sure if he’ll want to stay. We’ve both taken an early retirement and we’re both home all the time. I think he’d like a break from me. See you soon,

Mary

Hi Alice,

I’m Dan Sullivan, 53 years old, diagnosed with EOAD 3 years ago. It runs in my family. My mother, two uncles, and one of my aunts had it, and 4 of my cousins do. So I saw this coming and have been living with it in the family since I was a kid. Funny, didn’t make the diagnosis or living with it now any easier. My wife knows where you live. Not far from MGH. Near Harvard. My daughter went to Harvard. I pray every day that she doesn’t get this.

Dan

Hi Alice,

Thank you for your email and invitation. I was diagnosed with EOAD a year ago, like you. It was almost a relief. I thought I was going crazy. I was getting lost in conversations, having trouble finishing my own sentences, forgetting my way home, couldn’t understand the checkbook anymore, was making mistakes with the kids’ schedules (I have a 15-year-old daughter and a 13-year-old son). I was only 46 when the symptoms started, so of course, no one ever thought it could be Alzheimer’s.

I think the medications help a lot. I’m on Aricept and Namenda. I have good days and bad. On the good, people and even my family use it as an excuse to think that I’m perfectly fine, even making this up! I’m not that desperate for attention! Then, a bad day hits, and I can’t think of words or concentrate and I can’t multitask at all. I feel lonely, too. I can’t wait to meet you.

Cathy Roberts

P.S. Do you know about the Dementia Advocacy and Support Network International? Go to their website: www.dasninternational.org. It’s a wonderful site for people like us in early stages and with early-onset to talk, vent, get support, and share information.

There they were. And they were coming.

MARY, CATHY, AND DAN REMOVED their coats and found seats in the living room. Their spouses kept their coats on, bid them a reluctant good-bye, and left with John for coffee at Jerri’s.

Mary had chin-length blond hair and round, chocolate brown eyes behind a pair of dark-rimmed glasses. Cathy had a smart, pleasing face, and eyes that smiled before her mouth did. Alice liked her immediately. Dan had a thick mustache, a balding head, and a stocky build. They could’ve been professors visiting from out of town, members of a book club, or old friends.

“Would anyone like something to think?” asked Alice.

They stared at her and at one another, disinclined to answer. Were they all too shy or polite to be the first to speak up?

“Alice, did you mean ‘drink’?” asked Cathy.

“Yes, what’d I say?”

“You said ‘think.’”

Alice’s face flushed. Word substitution wasn’t the first impression she’d wanted to make.

“I’d actually like a cup of thinks. Mine’s been close to empty for days, I could use a refill,” said Dan.

They laughed, and it connected them instantly. She brought in the coffee and tea as Mary was telling her story.

“I was a real estate agent for twenty-two years. I suddenly started forgetting appointments, meetings, open houses. I showed up to houses with no keys. I got lost on my way to show a property in a neighborhood I’d known forever with the client in the car with me. I drove around for forty-five minutes when it should’ve taken less than ten. I can only imagine what she was thinking.