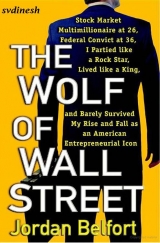

Текст книги "The Wolf of Wall Street "

Автор книги: Jordan Belfort

Жанр:

Биографии и мемуары

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 39 страниц)

“I want you to deal with all your problems by becoming rich! I want you to attack your problems head-on! I want you to go out and start spending money right now. I want you to leverage yourself. I want you to back yourself into a corner. Give yourself no choice but to succeed. Let the consequences of failure become so dire and so unthinkable that you’ll have no choice but to do whatever it takes to succeed.

“And that’s why I say: Act as if! Act as if you’re a wealthy man, rich already, and then you’ll surely become rich. Act as if you have unmatched confidence and then people will surely have confidence in you. Act as if you have unmatched experience and then people will follow your advice. And act as if you are already a tremendous success, and as sure as I stand here today—you willbecome successful!

“Now, this deal opens in less than an hour. So get on the fucking phone right this second and go A to Z through those client books and take no prisoners. Be ferocious! Be pit bulls! Be telephone terrorists! You do exactly as I say and, believe me, you’ll be thanking me a thousand times over a few hours from now, when every one of your clients is making money.”

With that, I walked off center stage to the sound of a thousand cheering Strattonites, who were already in the process of picking up their phones and following my very advice: ripping their clients’ eyeballs out.

CHAPTER 9

PLAUSIBLE DENIABILITY

At one p.m., the geniuses down at the National Association of Securities Dealers, the NASD, released Steve Madden Shoes for trading on the NASDAQ stock exchange under the four-letter trading symbol SHOO: pronounced shoe. How cute and appropriate that was!

And as part of their long-standing practice of having their heads up their asses, they reserved the distinguished honor of setting the price for the opening tick for me, the Wolf of Wall Street. It was just another in a long line of ill-conceived trading policies that were so absurd that they all but assured that every new issue coming out on the NASDAQ would be manipulated in one way or another, regardless of whether or not Stratton Oakmont was involved in it.

Just why the NASD had created a playing field that so clearly fucked over the customer was something I’d thought about often, and I’d come to the conclusion that it was because the NASD was a self-regulatory agency, “owned” by the very brokerage firms themselves. (In fact, Stratton Oakmont was a member too.)

In essence, the NASD’s true goal was to only appear to be on the side of the customer and to not actually be on the side of the customer. And, in truth, they didn’t even try too hard to do that. The effort was strictly cosmetic, just enough to avoid raising the ire of the SEC, who they were compelled to answer to.

So instead of allowing the natural balance between buyers and sellers to dictate where a stock should open, they reserved that incredibly valuable right for the lead underwriter, which in this particular case was me. I could choose whatever price I deemed appropriate, as arbitrary and capricious as it might be. In consequence, I decided to be very arbitrary and even more capricious, and I opened the units at $5.50 per, which afforded me the glorious opportunity of repurchasing my one million rathole units just there. And while I won’t deny that my ratholes would have liked to hold on to the units for a weeeeebit longer, they had no choice in the matter. After all, the buyback had been prearranged (a definite regulatory no-no), and they had just made a profit of $1.50 per unit for doing nothing and risking nothing—having bought and sold the units without even paying for the trade. And if they wanted to be included in the next deal, they had better follow the expected protocol, which was to shut the fuck up and say, “Thank you, Jordan!” and then lie through their teeth if they were ever questioned by a federal or state securities regulator as to why they sold their units so cheaply.

Either way, you really couldn’t question my logic in the matter. By 1:03 p.m.—just three minutes after I’d bought back my rathole units at $5.50 per—the rest of Wall Street had already driven the units up to $18. That meant I had locked in a profit of $12.5 million– $12.5 million! In three minutes!I’d made another million or so in investment-banking fees and stood to make another three or four million a few days from now—when I bought back the bridge-loan units, which were also in the hands of my ratholes. Ahhhh—ratholes! What a concept! And Steve himself was my biggest rathole of all. He was holding 1.2 million shares for me, the very shares NASDAQ had forced me to divest. At the current unit price of $18 (each unit consisting of one share of common stock and two warrants), the actual share price was $8. That meant that the shares Steve was holding for me were now worth just under $10 million! The Wolf strikes again!

It was now up to my loyal Strattonites to sell all this inflated stock to their clients. All this inflated stock—not just the one million units they had given to their own clients as part of the initial public offering but also my one million rathole units that were now being held in the firm’s trading account, along with 300,000 bridge-loan units I would be buying back in a few days…and then some additional stock I had to buy back from all the brokerage firms that had pushed the units up to $18 (doing the dirty work for me). They would be slowly selling their units back to Stratton Oakmont and locking in their own profit. All told, by the end of the day, I would need my Strattonites to raise approximately $30 million. That would more than cover everything, as well as give the firm’s trading account a nice little cushion against any pain-in-the-ass short-sellers, who might try to sell stock they didn’t even own (with the hopes of driving the price down so they could buy it back cheaper in the future). Thirty million was no problem for my merry band of brokers, especially after this morning’s meeting, which had them pitching their hearts and souls out like never before.

At this particular moment I was standing inside the firm’s trading room—looking over the shoulder of my head trader, Steve Sanders. I had one eye on a bank of computer monitors directly in front of Steve, while my other eye looked out a plate-glass window that faced the boardroom. The pace was absolutely frenetic. Brokers were screaming into their telephones like wild banshees. Every few seconds a young sales assistant with a lot of blond hair and a plunging neckline would come running up to the plate-glass window, press her breasts against it, and slip a stack of buy tickets through a narrow slot at the bottom. Then one of four order clerks would grab the tickets and input them into the computer network—causing them to pop up on the proprietary trading terminal in front of Steve, at which point he would execute them in accordance with the current market.

As I watched the orange-diode numbers flash across Steve’s terminal, I felt a twisted sense of pride over how those two morons from the SEC had been sitting in my conference room, searching the historical record for some sort of smoking gun, while I fired off a live bazooka under their noses. But I guess they’d been too busy freezing to death, as we listened to every word they said.

By now, more than fifty different brokerage firms were participating in the buying frenzy. What they all had in common, though, was that each one fully intended on selling every last share back to Stratton Oakmont at the end of the day, at the very top of the market. And with other brokerage firms doing the buying, it would now be impossible for the SEC to make the case that I had been the one who’d manipulated the units to $18. It was elegantly simple. How could I be at fault if I hadn’t been the one who’d driven the price of the stock up? In fact, I had actually been a seller the whole way. And I had sold the other brokerage firms just enough to wet their beaks, so they would continue to manipulate my new issues in the future—but not too much that it would become a major burden to me when I had to buy the stock back at the end of the trading day. It was a careful balance to strike, but the simple fact was that having other brokerage firms bidding up the price of Steve Madden Shoes created plausible deniability with the SEC. And, in a month from now, when they were subpoenaing my trading records, trying to reconstruct what had happened in those first few moments of trading, all they would see was that brokerage firms across America had bid up the price of Steve Madden Shoes, and that would be that.

Before I left the trading room, my final instructions to Steve were that under no circumstances was he to let the stock drop below $18. After all, I wasn’t about to shaft the rest of Wall Street after they’d been kind enough to manipulate my stock for me.

CHAPTER 10

THE DEPRAVED CHINAMAN

By four p.m. it was one for the record books.

The trading day was over, and the news that Steve Madden Shoes had been the most actively traded stock in America and, for that matter, the world had come skidding across the Dow Jones wire service for one and all to see. The world! Such audacity! Such sheer audacity!

Oh, yes, Stratton Oakmont had the power, all right. In fact, Stratton Oakmont wasthe power, and I, as Stratton’s leader, was wired into that very power and sat atop its pinnacle. I felt it surge through my very innards and resonate with my heart and soul and liver and loins. With more than eight million shares changing hands, the units had closed just below $19, up five hundred percent on the day, making it the largest percentage gainer on the NASDAQ, the NYSE, the AMEX, as well as any other stock exchange in the world. Yes, the world—from the OBX exchange way up north in the frozen wasteland of Oslo, Norway, all the way down south to the ASX exchange in the kangaroo paradise of Sydney, Australia.

Right now I was standing in the boardroom, casually leaning against my office’s plate-glass window, with my arms folded beneath my chest. It was the pose of the mighty warrior after the fray. The mighty roar of the boardroom was still going strong, but the tone was different now. It was less urgent, more subdued.

It was almost celebration time. I stuck my right hand in my pants pocket and did a quick check to make sure my six Ludes hadn’t fallen out or simply vanished into thin air. Quaaludes had a way of vanishing sometimes, although it usually had more to do with your “friends” snatching them from you—or you getting so stoned that you took them yourself and simply didn’t remember. That was the fourth phase of a Quaalude high and, perhaps, the most dangerous: the amnesia phase. The first phase was the tingle phase, next came the slur phase, then the drool phase, and then, of course, the amnesia phase.

Anyway, the drug-god had been kind to me, and the Quaaludes hadn’t vanished. I took a moment to roll them around in my fingertips, which gave me an irrational sense of joy. Then I began the process of calculating the appropriate time to take them, which was somewhere around 4:30 p.m., I figured, twenty-five minutes from now. That would give me fifteen minutes to hold the afternoon meeting, as well as enough time to supervise this afternoon’s act of depravity, which was a female head-shaving.

One of the young sales assistants, who was strapped for cash, had agreed to put on a Brazilian bikini and sit down on a wooden stool at the front of the boardroom and let us shave her head down to the skull. She had a great mane of shimmering blond hair and a wonderful set of breasts, which had recently been augmented to a D cup. Her reward would be $10,000 in cash, which she would use to pay for her breast job, which she’d just financed at twelve percent. So it was a win-win situation for everyone: In six months she’d have her hair back, and she’d own her D cups debt free.

I couldn’t help but wonder if I should’ve allowed Danny to bring a midget into the office. After all, what was so wrong with it? It sounded a bit off at first, but now that I’d had a little time to digest it, it didn’t seem so bad.

In essence, what it really boiled down to was that the right to pick up a midget and toss him around was just another currency due any mighty warrior, a spoil of war, so to speak. How else was a man to measure his success if not by playing out every one of his adolescent fantasies, regardless of how bizarre it might be? There was definitely something to be said for that. If precocious success brought about questionable forms of behavior, then the prudent young man should enter each unseemly act into the debit column on his own moral balance sheet and then offset it at some future point with an act of kindness or generosity (a moral credit, so to speak), when he became older and wiser and more sedate.

Yet, on the other hand, we might just be depraved maniacs—a self-contained society that had spiraled completely out of control. We Strattonites thrived on acts of depravity. We counted on them, in fact; I mean, we needed them to survive!

It was for this very reason that, after becoming completely desensitized to basic acts of depravity, the powers that be (namely, me) felt compelled to form an unofficial team of Strattonites—with Danny Porush as its proud leader—to fill the void. The team acted like a twisted version of the Knights Templar—whose never-ending quest to find the Holy Grail was the stuff of legend. But unlike the Knights Templar, the Stratton knights spent their time scouring the four corners of the earth for increasingly depraved acts, so the rest of the Strattonites could continue to get off. It wasn’t like we were heroin junkies or anything as tawdry as that; we were unadulterated adrenaline junkies, who needed higher and higher cliffs to dive off and shallower and shallower pools to land in.

The process had officially gotten under way in October 1989, when twenty-one-year-old Peter Galletta, one of the initial eight Strattonites, christened the building’s glass elevator with a quick blow job and an even quicker rear entry into the luscious loins of a seventeen-year-old sales assistant. She was Stratton’s first sales assistant, and, for better or worse, she was blond, beautiful, and wildly promiscuous.

At first I was shocked and had even considered firing Peter, for dipping his pen into the company inkwell. But within a week the young girl had proven to be a real team player—blowing all eight Strattonites, most of them in the glass elevator, and me under my desk. And she had a strange way of doing it, which became legendary among Strattonites. We called it the twist and jerk—where she’d use both hands at once, while she transformed her tongue into a whirling dervish. Anyway, about a month later, after a tiny bit of urging, Danny convinced me that it would be good if we both did her at the same time, which we did, on a Saturday afternoon while our wives were out shopping for Christmas dresses. Ironically, three years later, after bedding God only knew how many Strattonites, she finally married one. He was one of the original eight Strattonites and had seen her ply her trade countless times. But he didn’t care. Perhaps it was the twist and jerk that had got him! Whatever the case, he’d been only sixteen when he first came to work for me. He dropped out of high school to become a Strattonite—to live the Life. But after a short marriage, he became depressed and committed suicide. It would be Stratton’s first but not last suicide.

That aside, within the four walls of the boardroom, behavior of the normal sort was considered to be in bad taste, as if you were some sort of killjoy or something, looking to spoil the fun for everyone else. In a way, though, wasn’t the concept of depravity relative? The Romans hadn’t considered themselves to be depraved maniacs, had they? In fact, I’d be willing to bet that it all seemed normal to them as they watched their less-favored slaves being fed to the lions and their more-favored slaves fed them grapes.

Just then I saw the Blockhead walking toward me with his mouth open, his eyebrows high on his forehead, and his chin tilted slightly up. It was the eager expression of a man who’d been waiting half his life to ask a single question. Given the fact that it was the Blockhead, I had no doubt the question was either grossly stupid or grossly worthless. Whichever it was, I acknowledged him with a tilt of my own chin, and then I took a moment to regard him. In spite of having the squarest head on Long Island, he was actually good-looking. He had the soft round features of a little boy and was blessed with a reasonably good physique. He was of medium height and medium weight, which was surprising, considering from whose loins he’d emerged.

The Blockhead’s mother, Gladys Greene, was a big woman.

Everywhere.

Starting from the very top of her crown, where a beehive of pineapple blond hair rose up a good six inches above her broad Jewish skull, and all the way down to the thick callused balls of her size-twelve feet, Gladys Greene was big. She had a neck like a California redwood and the shoulders of an NFL linebacker. And her gut…well, it was big, all right, but it didn’t have an ounce of fat on it. It was the sort of gut you would normally find on a Russian power-lifter. And her hands were the size of meat hooks.

The last time a person really got under Gladys’s skin was while she was going through the checkout line at Grand Union. One of those typical Long Island Jewish women, with a big nose and the nasty habit of sticking it where it didn’t belong, made the sorry mistake of informing Gladys that she had exceeded the maximum number of items to pass through the express lane and still maintain the moral high ground. Gladys’s response was to turn on the woman and hit her full on with a right cross. With the woman still unconscious, Gladys calmly paid for her groceries and made a swift exit, her pulse never exceeding seventy-two.

So there was no leap of logic required to figure out why the Blockhead was only a smidgen saner than Danny. Yet, in the Blockhead’s defense, he had had a lot on his plate growing up. His father, who died of cancer when Kenny was only twelve years old, had owned a cigarette distributorship, and, unbeknownst to Gladys, it had been grossly mismanaged—owing hundreds of thousands in back taxes. And just like that, Gladys found herself in a desperate situation: a single mother on the brink of financial ruin.

What was Gladys to do? Fold up her tent? Apply for welfare, perhaps? Oh, no, not a chance! Using her strong maternal instincts, she recruited Kenny into the seedy underbelly of the cigarette-smuggling business—teaching him the little-known art of repackaging cartons of Marlboros and Lucky Strikes and then smuggling them from New York into New Jersey with counterfeit tax stamps, where they could pick up the difference in the spread. As luck would have it, the plan worked like a charm, and the family stayed afloat.

But that was only the beginning. When Kenny turned fifteen, his mother realized that he and his friends had started smoking a different type of cigarette, namely, joints. Had Gladys gotten pissed? Not in the least! Without a moment’s hesitation, she backed the budding Blockhead as a pot dealer—providing him with finance, encouragement, a safe haven to ply his trade, and, of course, protection, which was her specialty.

Oh, yes, Kenny’s friends were well aware of what Gladys Greene was capable of. They had heard the stories. But it never came down to violence. I mean, what sixteen-year-old kid wants a two-hundred-fifteen-pound Jewish mama showing up at their parents’ doorstep to collect a drug debt—especially when she’s sure to be wearing a purple polyester pantsuit, size-twelve purple pumps, and a pair of pink acrylic glasses with lenses the size of hubcaps?

But Gladys was only getting warmed up. After all, you could love pot or hate pot, but you had to respect it as the most reliable gateway drug in the marketplace, especially when it came to teenagers. In light of that, it wasn’t long before Kenny and Gladys realized there were other economic voids to be filled in Long Island’s teenage drug market. Oh, yes, that Bolivian marching powder, cocaine, offered too high a profit margin for ardent capitalists like Gladys and the Blockhead to resist. This time, though, they brought in a third partner, the Blockhead’s childhood friend Victor Wang.

Victor was an interesting sort, insofar as him being the biggest Chinaman to ever walk the planet. He had a head the size of a giant panda’s, slits for eyes, and a chest as broad as the Great Wall itself. In fact, the guy was a dead ringer for Oddjob, the hitman from the James Bond movie Goldfinger,who could knock your block off with a steel-rimmed bowler cap at two hundred paces.

Victor was Chinese by birth and Jewish by injection, having been raised amid the most savage young Jews anywhere on Long Island: the towns of Jericho and Syosset. It was from out of the very marrow of these two upper-middle-class Jewish ghettos that the bulk of my first hundred Strattonites had come, most of them former drug clients of Kenny’s and Victor’s.

And like the rest of Long Island’s educationally challenged dream-seekers, Victor had also fallen into my employ, albeit not at Stratton Oakmont. Instead, he was the CEO of the public company Judicate, which was one of my satellite ventures. Judicate’s offices were downstairs on the basement level, a mere stone’s throw away from the happy hit squad of NASDAQ hookers. Its business was Alternative Dispute Resolution, or ADR, which was a fancy phrase for using retired judges to arbitrate civil disputes between insurance companies and plaintiffs’ attorneys.

The company was barely breaking even now—proving to be yet another classic example of a business looking terrific on paper but not translating into the real world. Wall Street was chock-full of these kinds of concept companies. Sadly enough, a man in my line of work—namely, small-cap venture capital—seemed to be finding all of them.

Nevertheless, Judicate’s slow demise had become a real sore point with Victor, despite the fact that it wasn’t really his fault. The business was fundamentally flawed and no one could’ve made a success of it, or at least not much of one. But Victor was a Chinaman, and like most of his brethren, if he had a choice between losing face or cutting off his own balls and eating them, he would gladly take out a scissor and start snipping at his scrotal sac. But that wasn’t an option here. Victor had, indeed, lost face, and he was a problem that needed to be dealt with. And with the Blockhead constantly pleading Victor’s case, it had become a perpetual thorn in my side.

It was for this very reason that I wasn’t the least bit surprised when the first words out of the Blockhead’s mouth were, “Can we sit down with Victor later today and try to work things out?”

Feigning ignorance, I replied, “Work whatout, Kenny?”

“Come on,” he urged. “We need to talk with Victor about opening up his own firm. He wants your blessing and he’s driving me crazy about it!”

“He wants my blessing or my money? Which one?”

“He wants both,” said the Blockhead. As an afterthought, he added, “He needsboth.”

“Uh-huh,” I replied, in the tone of the unimpressed. “And if I don’t give it to him?”

The Blockhead let out a great blockheaded sigh. “What do you have against Victor? He’s already pledged his loyalty to you a thousand times over. And he’ll do it again—right now—in front of all three of us. I’m telling you—next to you, Victor’s the sharpest guy I know. We’ll make a fortune off him. I swear! He’s already found a broker dealer he could buy for next to nothing. It’s called Duke Securities. I think you should give him the money. All he needs is half a million—that’s it.”

I shook my head in disgust. “Save your pleas for when you really need them, Kenny. Anyway, now is not the time to be discussing the future of Duke Securities. I think this is slightly more important, don’t you?” I motioned to the front of the boardroom, where a bunch of sales assistants were setting up a mock barbershop.

Kenny cocked his head to the side and looked over at the barbershop with a confused look on his face, but he said nothing.

I took a deep breath and let it out slowly. “Listen, there are things about Victor that trouble me. And that shouldn’t be news to you—unless, of course, you’ve had your head up your ass for the last five years!” I started chuckling. “You don’t seem to get it, Kenny, you really don’t. You don’t see that with all Victor’s plotting and planning he’s gonna Sun Tzu himself to death. And all his face-saving bullshit—I haven’t got the time or inclination to deal with it. I swear to fucking God!

“Anyway, get this through your head: Victor—will—never—be—loyal. Ever!Not to you, not to me, and not to himself. He’ll cut off his own Chinese nose to spite his own Chinese face in the name of winning some imaginary war he’s fighting against no one but himself. You got it?” I smiled cynically.

I paused and softened my tone. “Anyway, listen for a second: You know how much I love you, Kenny. And you also know how much I respect you.” I fought the urge to chuckle with those last few words. “And because of those two things, I will sit down with Victor and try to placate him. But I’m not doing it because of Victor fucking Wang, who I detest. I’m doing it because of Kenny Greene, who I love. On a separate note, he can’t just walk away from Judicate. Not yet, at least. I’m counting on you to make sure he stays until I do what I need to do.”

The Blockhead nodded. “No problem,” he said happily. “Victor listens to me. I mean, if you only knew how…”

The Blockhead started spewing out blockheaded nonsense, but I immediately tuned out. In fact, by the look in his eyes, I knew he hadn’t grasped my meaning at all. In point of fact—it was I, not Victor, who had the most to lose if Judicate went belly up. I was the largest shareholder, owning a bit more than three million shares, while Victor held only stock options, which were worthless at the current stock price of two dollars. Still, as an owner of stock,my stake was worth $6 million—although the two-dollar share price was misleading. After all the company was performing so poorly that you couldn’t actually sell the stock without driving the price down into the pennies.

Unless, of course, you had an army of Strattonites.

Yet there was one hitch to this exit strategy—namely, that my stock wasn’t eligible for sale yet. I had bought my shares directly from Judicate under SEC Rule 144, which meant there was a two-year holding period before I could legally resell it. I was only one month shy of the two-year mark, so all I needed was Victor to keep things afloat a tiny bit longer. But this seemingly simple task was proving to be far more difficult than I’d anticipated. The company was bleeding cash like a hemophiliac in a rosebush.

In fact, now that Victor’s options were worthless, his sole compensation was a salary of $100,000 a year, which was a paltry sum compared to what his peers were making upstairs. And unlike the Blockhead, Victor was no fool; he was keenly aware that I would use the power of the boardroom to sell my shares as soon as they became eligible, and he was also aware that he could get left behind after they were sold—reduced to nothing more than the chairman of a worthless public company.

He had intimated this concern to me via the Blockhead, who he’d been using as a puppet since junior high school. And I had explained to Victor, more than once, that I had no intention of leaving him behind, that I would make him whole no matter what—even if it meant making him money as my rathole.

But the Depraved Chinaman couldn’t be convinced of that, not for more than a few hours at a time. It was as if my words went in one ear and out the other. The simple fact was that he was a paranoid son of a bitch. He had grown up an oversize Chinaman amid a ferocious tribe of savage Jews. In consequence, he suffered from a massive inferiority complex. He now resented all savage Jews, especially me, the most savage Jew of all. To date, I had outsmarted him, outwitted him, and outmaneuvered him.

It was out of his very ego, in fact, that Victor hadn’t become a Strattonite in the early days. So he went to Judicate instead. It was his way of breaking into the inner circle, a way to save face for not making the right decision back in 1988, when the rest of his friends had sworn loyalty to me and had become the first Strattonites. In Victor’s mind, Judicate was merely a way station to insinuate himself back into the queue, so that one day I would tap him on the shoulder and say, “Vic, I want you to open up your own brokerage firm, and here’s the money and expertise to do it.”

It was what every Strattonite dreamed of and something I touched upon in all my meetings—that if you continued to work hard and stay loyal, one day I’d tap you on the shoulder and set you up in business.

And then you would get truly rich.

I had done this twice so far: once with Alan Lipsky, my oldest and most trusted friend, who now owned Monroe Parker Securities; and a second time, with Elliot Loewenstern, another long-time friend, who now owned Biltmore Securities. Elliot had been my partner back in my ice-hustling days. During the summer, the two of us would go down to the local beach and hustle Italian ices blanket-to-blanket, and make a fortune. We would scream out our sales pitch as we carried around forty-pound Styrofoam coolers, running from the cops when they chased after us. And while our friends were either goofing off or working menial jobs for $3.50 an hour, we were earning $400 a day. Each summer we would each save twenty thousand dollars and use it during the winter months to pay our way through college.